Sovereignty in British Legal Doctrine*

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Part I Background and Summary

PART I BACKGROUND AND SUMMARY Chapter 1 BRITISH STATUTES IN IDSTORICAL PERSPECTIVE The North American plantations were not the earliest over seas possessions of the English Crown; neither were they the first to be treated as separate political entities, distinct from the realm of England. From the time of the Conquest onward, the King of England held -- though not necessarily simultaneously or continuously - a variety of non-English possessions includ ing Normandy, Anjou, the Channel Islands, Wales, Jamaica, Scotland, the Carolinas, New-York, the Barbadoes. These hold ings were not a part of the Kingdom of England but were govern ed by the King of England. During the early medieval period the King would issue such orders for each part of his realm as he saw fit. Even as he tended to confer more and more with the officers of the royal household and with the great lords of England - the group which eventually evolved into the Council out of which came Parliament - with reference to matters re lating to England, he did likewise with matters relating to his non-English possessions.1 Each part of the King's realm had its own peculiar laws and customs, as did the several counties of England. The middle ages thrived on diversity and while the King's writ was acknowledged eventually to run throughout England, there was little effort to eliminate such local practices as did not impinge upon the power of the Crown. The same was true for the non-Eng lish lands. An order for one jurisdictional entity typically was limited to that entity alone; uniformity among the several parts of the King's realm was not considered sufficiently important to overturn existing laws and customs. -

Orme) Wilberforce (Albert) Raymond Blackburn (Alexander Bell

Copyrights sought (Albert) Basil (Orme) Wilberforce (Albert) Raymond Blackburn (Alexander Bell) Filson Young (Alexander) Forbes Hendry (Alexander) Frederick Whyte (Alfred Hubert) Roy Fedden (Alfred) Alistair Cooke (Alfred) Guy Garrod (Alfred) James Hawkey (Archibald) Berkeley Milne (Archibald) David Stirling (Archibald) Havergal Downes-Shaw (Arthur) Berriedale Keith (Arthur) Beverley Baxter (Arthur) Cecil Tyrrell Beck (Arthur) Clive Morrison-Bell (Arthur) Hugh (Elsdale) Molson (Arthur) Mervyn Stockwood (Arthur) Paul Boissier, Harrow Heraldry Committee & Harrow School (Arthur) Trevor Dawson (Arwyn) Lynn Ungoed-Thomas (Basil Arthur) John Peto (Basil) Kingsley Martin (Basil) Kingsley Martin (Basil) Kingsley Martin & New Statesman (Borlasse Elward) Wyndham Childs (Cecil Frederick) Nevil Macready (Cecil George) Graham Hayman (Charles Edward) Howard Vincent (Charles Henry) Collins Baker (Charles) Alexander Harris (Charles) Cyril Clarke (Charles) Edgar Wood (Charles) Edward Troup (Charles) Frederick (Howard) Gough (Charles) Michael Duff (Charles) Philip Fothergill (Charles) Philip Fothergill, Liberal National Organisation, N-E Warwickshire Liberal Association & Rt Hon Charles Albert McCurdy (Charles) Vernon (Oldfield) Bartlett (Charles) Vernon (Oldfield) Bartlett & World Review of Reviews (Claude) Nigel (Byam) Davies (Claude) Nigel (Byam) Davies (Colin) Mark Patrick (Crwfurd) Wilfrid Griffin Eady (Cyril) Berkeley Ormerod (Cyril) Desmond Keeling (Cyril) George Toogood (Cyril) Kenneth Bird (David) Euan Wallace (Davies) Evan Bedford (Denis Duncan) -

'The Oriental Jennings' an Archival Investigation Into Sir Ivor Jennings’ Constitutional Legacy in South Asia

'The Oriental Jennings' An Archival Investigation into Sir Ivor Jennings’ Constitutional Legacy in South Asia Mara Malagodi LSE Law Department New Academic Building 54 Lincolns Inn Fields London WC2A 3LJ ABSTRACT The article investigates the legacy of British constitutionalist Sir Ivor Jennings (1903‐1965) in South Asia. In 1940, when Jennings moved to Sri Lanka, a new phase of prolific writing on the laws of the British Empire and Commonwealth began for him, together with a practical engagement with constitution‐making experiences in decolonising nations across Asia and Africa. The archival material relating to Jennings’ work on postcolonial constitutional issues forms part of the collection of Jennings’ Private Papers held at the Institute of Commonwealth Studies in London. This article seeks to explain why this material has until now remained so under‐researched. INTRODUCTION The present article explores a neglected aspect of the life and work of noted British constitutionalist Sir Ivor Jennings (1903‐1965): his engagement with constitutional issues in the postcolonial world. In particular, the analysis investigates Jennings’ constitutional legacy in South Asia where he was involved, both academically and professionally, with most of the region’s jurisdictions.1 Jennings played a direct role in Sri Lanka (1940‐1954), the Maldives (1952‐1953), Pakistan (1954‐1955), and Nepal (1958), and had a long‐term indirect engagement with India. In 1940, Jennings moved to Sri Lanka – where he resided until his appointment in 1954 as Master of Trinity College in Cambridge – and became progressively involved with constitution‐making processes and constitutional change across the decolonising world. I refer to this period of Jennings’ life experiences, to the body of literature pertaining to the postcolonial world that he produced, and to his advisory work in decolonising countries as the ‘Oriental Jennings’ – a body of literature largely ignored by academic scholarship.2 The paper seeks to explain the reasons for this scholarly silence. -

Introduction

INTRODUCTION ‘We have the advice of the greatest living authority on Constitutional Law regarding the British Commonwealth – Dr Jennings’, proclaimed the Leader of the Ceylon Senate in December 1947 in a parliamentary debate on the future constitutional design of the island.1 So in thrall to William Ivor Jennings was the powerful and soon to be first prime minister of independent Ceylon, D.S. Senanayake, that in the same debate it was contemptuously suggested that his initials stood for ‘Dominion Status Senanayake’, a form of independence that Jennings advocated as Senanayake’s pervasive and persuasive adviser.2 Senanayake was never in doubt as to the value of Jennings and publicly expressed his gratitude by delivering to the Englishman a knighthood, on his advice, for services to Ceylon, less than six months later in the King’s 1948 Birthday Honours List. Ivor Jennings was born in Bristol on 16 May 1903.Hehada remarkable career stretching across the world as a constitutional scholar in the heyday of decolonization before his death in Cambridge at just sixty-two on 19 December 1965.3 After studying mathematics and law, he obtained a first-class degree for the law tripos in 1924–1925 while at St Catharine’s College, Cambridge. After a short time as a law lecturer at the University of Leeds, he went to the London School of Economics (LSE) in 1929, where he rose to become Reader in English Law. While at the LSE, Jennings published some of his most famous and influential works, including The Law and the Constitution (1933), Cabinet Government (1936), and Parliament (1939). -

Comparison of Constitutionalism in France and the United States, A

A COMPARISON OF CONSTITUTIONALISM IN FRANCE AND THE UNITED STATES Martin A. Rogoff I. INTRODUCTION ....................................... 22 If. AMERICAN CONSTITUTIONALISM ..................... 30 A. American constitutionalism defined and described ......................................... 31 B. The Constitution as a "canonical" text ............ 33 C. The Constitution as "codification" of formative American ideals .................................. 34 D. The Constitution and national solidarity .......... 36 E. The Constitution as a voluntary social compact ... 40 F. The Constitution as an operative document ....... 42 G. The federal judiciary:guardians of the Constitution ...................................... 43 H. The legal profession and the Constitution ......... 44 I. Legal education in the United States .............. 45 III. THE CONsTrrTION IN FRANCE ...................... 46 A. French constitutional thought ..................... 46 B. The Constitution as a "contested" document ...... 60 C. The Constitution and fundamental values ......... 64 D. The Constitution and nationalsolidarity .......... 68 E. The Constitution in practice ...................... 72 1. The Conseil constitutionnel ................... 73 2. The Conseil d'ttat ........................... 75 3. The Cour de Cassation ....................... 77 F. The French judiciary ............................. 78 G. The French bar................................... 81 H. Legal education in France ........................ 81 IV. CONCLUSION ........................................ -

The Medieval Parliament

THE MEDIEVAL PARLIAMENT General 4006. Allen, John. "History of the English legislature." Edinburgh Review 35 (March-July 1821): 1-43. [Attributed in the Wellesley Index; a review of the "Reports on the Dignity of a Peer".] 4007. Arnold, Morris S. "Statutes as judgments: the natural law theory of parliamentary activities in medieval England." University of Pennsylvania Law Review 126 (1977-78): 329-43. 4008. Barraclough, G. "Law and legislation in medieval England." Law Quarterly Review 56 (1940): 75-92. 4009. Bemont, Charles. "La séparation du Parlement anglais en deux Chambres." In Actes du premier Congrès National des Historiens Français. Paris 20-23 Avril 1927, edited by Comite Français des Sciences Historiques: 33-35. Paris: Éditions Rieder, 1928. 4010. Betham, William. Dignities, feudal and parliamentary, and the constitutional legislature of the United Kingdom: the nature and functions of the Aula Regis, the Magna Concilia and the Communa Concilia of England, and the history of the parliaments of France, England, Scotland, and Ireland, investigated and considered with a view to ascertain the origin, progress, and final establishment of legislative parliaments, and the dignity of a peer, or Lord of Parliament. London: Thomas and William Boone, 1830. xx, 379p. [A study of the early history of the Parliaments of England, Ireland and Scotland, with special emphasis on the peerage; Vol. I only published.] 4011. Bodet, Gerald P. Early English parliaments: high courts, royal councils, or representative assemblies? Problems in European civilization. Boston, Mass.: Heath, 1967. xx,107p. [A collection of extracts from leading historians.] 4012. Boutmy, E. "La formation du Parlement en Angleterre." Revue des Deux Mondes 68 (March-April 1885): 82-126. -

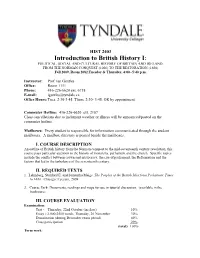

Introduction to British History I

HIST 2403 Introduction to British History I: POLITICAL, SOCIAL AND CULTURAL HISTORY OF BRITAIN AND IRELAND, FROM THE NORMAN CONQUEST (1066) TO THE RESTORATION (1660) Fall 2009, Room 2082,Tuesday & Thursday, 4:00--5:40 p.m. Instructor: Prof. Ian Gentles Office: Room 1111 Phone: 416-226-6620 ext. 6718 E-mail: [email protected] Office Hours: Tues. 2:30-3:45, Thurs. 2:30- 3:45, OR by appointment Commuter Hotline: 416-226-6620 ext. 2187 Class cancellations due to inclement weather or illness will be announced/posted on the commuter hotline. Mailboxes: Every student is responsible for information communicated through the student mailboxes. A mailbox directory is posted beside the mailboxes. I. COURSE DESCRIPTION An outline of British history from the Norman conquest to the mid-seventeenth century revolution, this course pays particular attention to the history of monarchy, parliament and the church. Specific topics include the conflict between crown and aristocracy, the rise of parliament, the Reformation and the factors that led to the turbulence of the seventeenth century. II. REQUIRED TEXTS 1. Lehmberg, Stanford E. and Samantha Meigs. The Peoples of the British Isles from Prehistoric Times to 1688 . Chicago: Lyceum, 2009 2. Course Pack: Documents, readings and maps for use in tutorial discussion. (available in the bookstore) III. COURSE EVALUATION Examination : Test - Thursday, 22nd October (in class) 10% Essay - 2,000-2500 words, Thursday, 26 November 30% Examination (during December exam period) 40% Class participation 20% (total) 100% Term work : a. You are expected to attend the tutorials, preparing for them through the lectures and through assigned reading. -

Nationalism, Constitutionalism and Sir Ivor Jennings' Engagement with Ceylon

Edinburgh Research Explorer 'Specialist in omniscience'? Nationalism, constitutionalism and Sir Ivor Jennings' engagement with Ceylon Citation for published version: Welikala, A 2016, 'Specialist in omniscience'? Nationalism, constitutionalism and Sir Ivor Jennings' engagement with Ceylon. in H Kumarasingham (ed.), Constitution-making in Asia: Decolonisation and State-building in the Aftermath of the British Empire. Routledge Studies in the Modern History of Asia, Routledge, Abingdon; New York, pp. 112-136. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781315629797 Digital Object Identifier (DOI): 10.4324/9781315629797 Link: Link to publication record in Edinburgh Research Explorer Document Version: Peer reviewed version Published In: Constitution-making in Asia Publisher Rights Statement: This is an Accepted Manuscript of a book chapter published by Routledge in Constitution-making in Asia: Decolonisation and State-Building in the Aftermath of the British Empire on 31/3/2016, available online: https://www.routledge.com/Constitution-making-in-Asia-Decolonisation-and-State-Building-in-the- Aftermath/Kumarasingham/p/book/9780415734585 General rights Copyright for the publications made accessible via the Edinburgh Research Explorer is retained by the author(s) and / or other copyright owners and it is a condition of accessing these publications that users recognise and abide by the legal requirements associated with these rights. Take down policy The University of Edinburgh has made every reasonable effort to ensure that Edinburgh Research Explorer content complies with UK legislation. If you believe that the public display of this file breaches copyright please contact [email protected] providing details, and we will remove access to the work immediately and investigate your claim. Download date: 01. -

The English Revolution in Historiographical Perspective

The English Revolution in Historiographical Perspective Daniel M. Roberts, Jr. Three hundred years have passed since native Englishmen last made war on each other. Yet, even after the Restoration of the House of Stuart, a great struggle of interpretation continued; men felt compelled to explain the war, its causes, circumstances, and results. Benedetto Croce (1866-1952) observed that all history is contemporary history. One need search no further for the truth of this dictum than the prodigious corpus of scholarly disputation seeking to interpret the English Revolution. Each century has provided fresh insights into the war, and the literature on this conflict serves to remind us that a historian's writing reveals as much about the writer as it does about the subject. The task at band is to fashion a description of the scholars who have investigated those civil distempers which gripped England in the mid-seventeenth century, striving, by this, to understand more of the subject by examining the examiners. The study of the English Revolution is a case study of historiogra phical dispute-a veritable panoply of learned pyrotechnics. Any analysis of this subject is complicated by the emotional investment common to those writing about civil conflict on their native soil; objectivity tends to suffer. This requires unhesitating skepticism when dealing with interpre tive writing. Despite the ritualistic protestations of pure and disinterested analysis, purged of any partisan presupposition, authors rarely become, as Edward Hyde, First Earl of Clarendon (1609-74), claimed to be, free from "any of those passions which naturally transport men with prejudice towards the persons whom they are obliged to mention, and whose actions Daniel M. -

The Making of Englishmen Studies in the History of Political Thought

The Making of Englishmen Studies in the History of Political Thought Edited by Terence Ball, Arizona State University JÖrn Leonhard, Albert-Ludwigs-Universität Freiburg Wyger Velema, University of Amsterdam Advisory Board Janet Coleman, London School of Economics and Political Science, UK Vittor Ivo Comparato, University of Perugia, Italy Jacques Guilhaumou, CNRS, France John Marshall, Johns Hopkins University, Baltimore, USA Markku Peltonen, University of Helsinki, Finland VOLUME 8 The titles published in this series are listed at brill.com/ship The Making of Englishmen Debates on National Identity 1550–1650 By Hilary Larkin LEIDEN • BOSTON 2014 This is an open access title distributed under the terms of the CC BY-NC 4.0 license, which permits any non-commercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author(s) and source are credited. Further information and the complete license text can be found at https://creativecommons.org/licenses/ by-nc/4.0/ The terms of the CC license apply only to the original material. The use of material from other sources (indicated by a reference) such as diagrams, illustrations, photos and text samples may require further permission from the respective copyright holder. An electronic version of this book is freely available, thanks to the support of libraries working with Knowledge Unlatched. More information about the initiative can be found at www. knowledgeunlatched.org. Cover illustration: Titian (c1545) Portrait of a Young Man (The Young Englishman). Galleria Palatina (Palazzo Pitti), Florence, Italy. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Larkin, Hilary. The making of Englishmen : debates on national identity, 1550-1650 / by Hilary Larkin. -

Restoration Period Historical Overview

Restoration period: A Historical Overview • Charles II’s accession in 1660 ending the period known in Latin as ‘Interregnum’ • The arrival of Kingship ended two decades of Civil Wars across Britain • Profound hope was restored among people that peace shall be established. • Yet conflicts in minor measure continued between three kingdoms. • Radical differences in religious and political affiliations continued. • It was also a period of colonial expansion. More facts on Restoration • In the Declaration of Breda(1660) Charles II promised “liberty to tender consciences” (religious toleration) • Act of Uniformity (1662): it required that ministers agree to an Episcopalian form of church government, with Bishops running the Church as opposed to a Presbyterian form run by the congregations’ membership. It excluded both the radical Protestants and Roman Catholics. Charles II tried to overturn this act, but Parliament made it a law in 1663. Those who refused to accept the act came to be called ‘Dissenters’ • The conflicting religious affiliations of these two groups were compounded by the differences between the three kingdoms. • Ireland had a majority of Roman Catholic population; Scotland had a Presbytarian church structure; and England had an Episcopalian church structure. • The Treaty of Dove: A secret alliance Charles II made with Louis IV, the Catholic King of France, for religious toleration and accommodation of Roman Catholics. It sparked off further controversies and conflicts as those that ended his father’s reign and life. Other developments • Glorious Revolution (1688)/(The Blood-less Revolution): The overthrow of the Catholic king, James II, who was replaced by his Protestant daughter Mary and her Dutch husband, William. -

The RISE of DEMOCRACY REVOLUTION, WAR and TRANSFORMATIONS in INTERNATIONAL POLITICS SINCE 1776

Macintosh HD:Users:Graham:Public:GRAHAM'S IMAC JOBS:15554 - EUP - HOBSON:HOBSON NEW 9780748692811 PRINT The RISE of DEMOCRACY REVOLUTION, WAR AND TRANSFORMATIONS IN INTERNATIONAL POLITICS SINCE 1776 CHRISTOPHER HOBSON Macintosh HD:Users:Graham:Public:GRAHAM'S IMAC JOBS:15554 - EUP - HOBSON:HOBSON NEW 9780748692811 PRINT THE RISE OF DEMOCRACY Macintosh HD:Users:Graham:Public:GRAHAM'S IMAC JOBS:15554 - EUP - HOBSON:HOBSON NEW 9780748692811 PRINT Macintosh HD:Users:Graham:Public:GRAHAM'S IMAC JOBS:15554 - EUP - HOBSON:HOBSON NEW 9780748692811 PRINT THE RISE OF DEMOCRACY Revolution, War and Transformations in International Politics since 1776 Christopher Hobson Macintosh HD:Users:Graham:Public:GRAHAM'S IMAC JOBS:15554 - EUP - HOBSON:HOBSON NEW 9780748692811 PRINT © Christopher Hobson, 2015 Edinburgh University Press Ltd The Tun – Holyrood Road 12 (2f) Jackson’s Entry Edinburgh EH8 8PJ www.euppublishing.com Typeset in 11 /13pt Monotype Baskerville by Servis Filmsetting Ltd, Stockport, Cheshire, and printed and bound in Great Britain by CPI Group (UK) Ltd, Croydon CR0 4YY A CIP record for this book is available from the British Library ISBN 978 0 7486 9281 1 (hardback) ISBN 978 0 7486 9282 8 (webready PDF) ISBN 978 0 7486 9283 5 (epub) The right of Christopher Hobson to be identified as author of this work has been asserted in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988 and the Copyright and Related Rights Regulations 2003 (SI No. 2498). Macintosh HD:Users:Graham:Public:GRAHAM'S IMAC JOBS:15554 - EUP - HOBSON:HOBSON NEW 9780748692811