CSFI Monks Book UK.Pmd

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

South Scotland Election Agents

OFFICIAL Scottish Parliamentary Notice of Appointment of Election Agents and Sub-Agents Election Region SOUTH SCOTLAND Date of poll Thursday 6 May 2021 The following is a notice of Election Agents appointed by Parties and Individual Candidates in the election of Members of the Scottish Parliament for the above Region. I, Lorna Meahan, Depute Regional Returning Officer, hereby give notice that the following names of Election Agents of Parties and Individual candidates at this election, and the addresses of the offices of such Election Agents to which all claims, notices, writs, summons, and other documents addressed to them may be sent, have respectively been declared in writing to me as follows: Name of Party Name of Agent Offices of Election Agent to which claims etc may be sent Abolish the Scottish Parliament Party John Mortimer Flat 2/2, 2 Rhynie Drive, Glasgow, G51 2LE Alba Party Isabella Zambonini 42 Market Street, Ellon, Aberdeenshire, AB41 9JD All for Unity James Giles Suite 2, Fullarton House, 4 Fullarton Street, Ayr, KA7 1UB Freedom Alliance- Integrity, Society, Economy Mary Steven 9 Ralston Road, Barrhead, East Renfrewshire, G78 2QQ Independent Green Voice Alistair McConnachie Clyde Offices, 2nd Floor, 48 West George Street, Glasgow, G2 1BP Reform UK Martyn Greene 7/9 North St David Street, Edinburgh, EH2 1AW Scotia Future Charles Brodie 23 Maybole Road, Ayr, KA7 2PZ Scottish Conservative and Unionist Party Mark McInnes 67 Northumberland Street, Edinburgh, EH3 6JG Scottish Family Party Michael Willis 29 Coney Park, Stirling, -

Why Some People Switch Political Parties: New Research 13 July 2021, by Paul Webb and Tim Bale

Why some people switch political parties: New research 13 July 2021, by Paul Webb and Tim Bale Our new research sheds light on the truth of party- switching politics—how many people really switch, why people are motivated to do so, and whether the claims of entryism are credible. Patterns of party-switching We surveyed nearly 7,000 members of British political parties (including registered Brexit Party supporters) within two weeks of the 2019 general election. When we analyzed the data, we found a remarkably high proportion of our sample (23%) claimed to have previously been—or, if we allow for registered Brexit Party supporters as well, currently were—members of a different political party than the Credit: CC0 Public Domain one to which they were now affiliated. Some 29% of Tory members who admitted in 2019 to having been members of other parties claim to Why do some people switch political parties? After have been UKIP members. Interestingly, though, all, if someone is committed enough to a particular virtually as many were former Labor members. As a vision of politics, wouldn't they be relatively proportion of all Conservative Party grassroots immune to the charms of its competitors? members, these figures amount to 3% who were former members of UKIP, 4.5% who were It turns out, however, that switching parties at simultaneously Brexit Party supporters, and 4% grassroots membership level is by no means who were ex-Labor members. uncommon, even giving rise in some quarters to accusations of "entryism." This puts into perspective the scale of the entryist phenomenon. -

Case Study on the United Kingdom and Brexit Juliane Itta & Nicole Katsioulis the Female Face of Right-Wing Populism and Ex

Triumph of The women? The Female Face of Right-wing Populism and Extremism 02 Case study on the United Kingdom and Brexit Juliane Itta & Nicole Katsioulis 01 Triumph of the women? The study series All over the world, right-wing populist parties continue to grow stronger, as has been the case for a number of years – a development that is male-dominated in most countries, with right-wing populists principally elected by men. However, a new generation of women is also active in right-wing populist parties and movements – forming the female face of right-wing populism, so to speak. At the same time, these parties are rapidly closing the gap when it comes to support from female voters – a new phenomenon, for it was long believed that women tend to be rather immune to right-wing political propositions. Which gender and family policies underpin this and which societal trends play a part? Is it possible that women are coming out triumphant here? That is a question that we already raised, admittedly playing devil’s advocate, in the first volume of the publication, published in 2018 by the Friedrich-Ebert-Stiftung Triumph of the women? The Female Face of the Far Right in Europe. We are now continuing this first volume with a series of detailed studies published at irregular intervals. This is partly in response to the enormous interest that this collection of research has aroused to date in the general public and in professional circles. As a foundation with roots in social democracy, from the outset one of our crucial concerns has been to monitor anti-democratic tendencies and developments, while also providing information about these, with a view to strengthening an open and democratic society thanks to these insights. -

Senedd Election South Wales Central Local Results Vale of Glamorgan

Senedd Cymru Elections: 6 May 2021 Local Totals for the South Wales Central Region: Vale of Glamorgan Constituency I Debbie Marles Constituency Returning Officer for the Vale of Glamorgan constituency declare that the total number of votes given to each party and individual candidate at the regional election in the Vale of Glamorgan constituency was as follows: Yr wyf i ar ran y Swyddog Canlyniadau Etholaethol ar gyfer etholaeth Bro Morgannwg yn datgan bod cyfanswm nifer y pleidleisiau a roddwyd i bob plaid ac ymgeisydd unigol yn yr etholiad rhanbarthol ym Mro Morgannwg fel y ganlyn: Candidate name Description (if any) Total number of votes for candidate ABOLISH THE WELSH 1875 ASSEMBLY PARTY BRITAIN’S COMMUNIST 67 PARTY / PLAID GOMIWNYDDOL PRYDAIN CEIDWADWYR CYMREIG / 15232 WELSH CONSERVATIVES 1936 GREEN PARTY / PLAID WERDD GWLAD – PLAID 185 ANNIBYNIAETH CYMRU / GWLAD – THE WELSH INDEPENDENCE PARTY 189 NO MORE LOCKDOWNS 5291 PLAID CYMRU - THE PARTY OF WALES PROPEL: WALES NEEDS 474 CHAMPIONS / PROPEL: MAE CYMRU ANGEN PENCAMPWYR 370 REFORM UK – CHANGING POLITICS FOR GOOD 562 UKIP SCRAP THE ASSEMBLY / SENEDD 15150 WELSH LABOUR / LLAFUR CYMRU WELSH LIBERAL 1196 DEMOCRATS – PUT RECOVERY FIRST / DEMOCRATIAID RHYDDFRYDOL CYMRU – ADFYWIO YW’R FLAENORIAETH WELSH TRADE UNIONIST 60 AND SOCIALIST COALITION WORKERS PARTY 87 COULTHARD, ALAN Independent / Annibynnol 142 TERENCE The total number of ballot papers rejected at the Regional Election in the Vale of Glamorgan Constituency was 270 Cyfanswm nifer y papurau pleidleisio a wrthodwyd oedd 270 The -

Political Parties and Candidates

Scottish Parliament Election Date of Election: Thursday, 6 May 2021 Highlands and Islands Region List of Registered Political Parties and Independent Candidates ABOLISH THE SCOTTISH PARLIAMENT PARTY Abolish Scottish Parliament – Save £100,000,000 Yearly JACK MALCOLM ALBA PARTY KIRK TORRANCE; CRAIG BERRY; JOSH ROBERTSON; JUDITH REID ALL FOR UNITY All 4 Unity - No to Separatism MOIRA RAMAGE; PATRICIA WATSON; ROBBIE GORDON MUNRO; DONALD MACLEOD BOYD; PAUL BURROWS; ALASTAIR KENNEDY; PAUL BRADBURN FREEDOM ALLIANCE- INTEGRITY, SOCIETY, ECONOMY Freedom Alliance. Scotland's Opposition to Lockdown TINA DEBORAH MCCAFFERY; EMMA ALICE IDZIKOWSKA; PHIL BREED; GARY ALAN CHEESMAN; ANNE MCCLOSKEY REFORM UK ReformUK - Changing Politics for Good SANDRA SKINNER; ARTHUR LESLIE DURANCE; KATE BROWNLIE; CATHERINE ELIZABETH MARY MOUNT RESTORE SCOTLAND BRIAN NUGENT; ANDREW ROSS MACDONALD SCOTTISH CONSERVATIVE AND UNIONIST PARTY DOUGLAS ROSS; EDWARD MOUNTAIN; DONALD CAMERON; JAMIE HALCRO JOHNSTON; TIM EAGLE; ELLA ROBERTSON McKAY; STRUAN MACKIE; SAM BOWN; GAVIN BERKENHEGER; NICK TULLOCH SCOTTISH FAMILY PARTY Scottish Family Party: Pro-Family, Pro-Marriage, Pro-Life MICHAEL DENNIS WILLIS; PHILIPP TANZER; SHENA MARGARET McLELLAND; SOPHIE GENEVIEVE MARIE HENDRY; DOLORES VERONICA HUGHES SCOTTISH GREEN PARTY Scottish Greens ARIANE CLAIRE BURGESS; ANNE KATHERINE THOMAS; FABIO VILLANI; STEVE SANKEY; DEBRA JANE NICOLSON; SAND OWSNETT; TOPHER DAWSON; LISA JANE MEAD; CHRIS BALLANCE; ISABELLA ROSA LILIAN SUMSION; PHYL STUART MEYER; LUNA ERIN LAVENTHIA MARTIN SCOTTISH LABOUR -

Draft House of Lords Reform Bill

House of Commons Joint Committee on the Draft House of Lords Reform Bill Draft House of Lords Reform Bill Report Session 2010–12 Volume III Other written evidence Ordered by the House of Lords to be printed 26 March 2012 Ordered by the House of Commons to be printed 26 March 2012 HL Paper 284–III HC 1313–III Published on 23 April 2012 by authority of the House of Commons London: The Stationery Office Limited £0.00 The Joint Committee on the Draft House of Lords Reform Bill The Joint Committee on the Draft House of Lords Reform Bill was appointed by the House of Commons on 23 June 2011 and by the House of Lords on 6 July 2011 to examine the Draft House of Lords Reform Bill and report to both Houses by 27 March 2012. It has now completed its work. Membership HOUSE OF LORDS HOUSE OF COMMONS Baroness Andrews Gavin Barwell MP Bishop of Leicester Mr Tom Clarke MP Lord Hennessy of Nympsfield Ann Coffey MP Lord Norton of Louth Bill Esterson MP Lord Richard (Chair) Oliver Heald MP Lord Rooker Tristram Hunt MP Baroness Scott of Needham Market Mrs Eleanor Laing MP Baroness Shephard of Northwold Dr William McCrea MP Baroness Symons of Vernham Dean Dr Daniel Poulter MP Lord Trefgarne Laura Sandys MP Lord Trimble John Stevenson MP Lord Tyler John Thurso MP Baroness Young of Hornsey Malcolm Wicks MP Powers The Committee has the power to require the submission of written evidence and documents, to examine witnesses, to meet at any time (except when Parliament is prorogued or dissolved), to adjourn from place to place, to appoint specialist advisers, and to make Reports to both Houses. -

Election 2001 Campaign Spending We Are an Independent Body That Was Set up by Parliament

Election 2001 Campaign spending We are an independent body that was set up by Parliament. We aim to gain public confidence and encourage people to take part in the democratic process within the United Kingdom by modernising the electoral process, promoting public awareness of electoral matters, and regulating political parties. On 1 April 2002, The Boundary Committee for England (formerly the Local Government Commission for England) became a statutory committee of The Electoral Commission. Its duties include reviewing local election boundaries. © The Electoral Commission 2002 ISBN: 1-904363-08-3 1 Contents List of tables, appendices and returns 2 Conclusions 45 Preface 5 Political parties 45 Executive summary 7 Third parties 46 Spending by political parties 7 Candidates’ expenses 46 Spending by third parties 7 Future work programme 47 Spending by candidates 7 Introduction 9 Appendices The role of The Electoral Commission 10 Appendix 1 49 Campaign expenditure by political parties 11 Appendix 2 50 The spending limit 12 Appendix 3 87 Interpretation of legislation 12 Appendix 4 89 Public and media interest in the campaign 13 Appendix 5 90 Commission guidance 13 Appendix 6 97 Completing and reviewing the expenditure returns 13 Candidates’ election expenses at the Analysis of returns 14 2001 general election 99 Northern Ireland analysis 15 Great Britain analysis 17 Problems in categorising expenditure 18 Breakdown of total expenditure: the main three British parties 18 Other parties and trends 19 Apportionment and spending in England, Scotland -

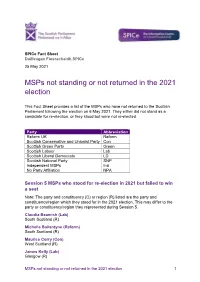

Msps Not Standing Or Not Returned in the 2021 Election

SPICe Fact Sheet Duilleagan Fiosrachaidh SPICe 25 May 2021 MSPs not standing or not returned in the 2021 election This Fact Sheet provides a list of the MSPs who have not returned to the Scottish Parliament following the election on 6 May 2021. They either did not stand as a candidate for re-election, or they stood but were not re-elected. Party Abbreviation Reform UK Reform Scottish Conservative and Unionist Party Con Scottish Green Party Green Scottish Labour Lab Scottish Liberal Democrats LD Scottish National Party SNP Independent MSPs Ind No Party Affiliation NPA Session 5 MSPs who stood for re-election in 2021 but failed to win a seat Note: The party and constituency (C) or region (R) listed are the party and constituency/region which they stood for in the 2021 election. This may differ to the party or constituency/region they represented during Session 5. Claudia Beamish (Lab) South Scotland (R) Michelle Ballantyne (Reform) South Scotland (R) Maurice Corry (Con) West Scotland (R) James Kelly (Lab) Glasgow (R) MSPs not standing or not returned in the 2021 election 1 Gordon Lindhurst (Con) Lothian (R) Joan McAlpine (SNP) South Scotland (R) John Scott (Con) Ayr (C) Paul Wheelhouse (SNP) South Scotland (R) Andy Wightman (Ind) Highlands and Islands (R) MSPs who were serving at the end of Parliamentary Session 5 but chose not to stand for re-election in 2021 Bill Bowman (Con) North East Scotland (R) Aileen Campbell (SNP) Clydesdale (C) Peter Chapman (Con) North East Scotland (R) Bruce Crawford (SNP) Stirling (C) Roseanna Cunningham (SNP) -

IPSOS MORI POLITICAL MONITOR June 2021

IPSOS MORI POLITICAL MONITOR June 2021 © Ipsos | Doc Name | Month Year | Version # | Public | Internal/Client Use Only | Strictly Confidential VOTING INTENTION © Ipsos | Doc Name | Month Year | Version # | Public | Internal/Client Use Only | Strictly Confidential Voting Intention: June 2021 How do you intend to vote in the General Election? Will you vote…? Headline voting intention All giving a voting intention Conservative 44% Conservative 40% Labour 35% Labour 37% Lib Dems 6% Lib Dem 8% Green 7% Green 5% Other 8% Other 10% Conservative lead = +9 Conservative lead = +3 th rd Base: 1,002 British adults 18+, 28 May – 3 June 2021; Headline Voting Intention: all 9/10 certain to vote, always/usually/it depends vote in General Elections = 637. Margin of error is Source: Ipsos MORI Political Monitor displayed at +/- 4% All polls are subject to a wide range of potential sources of error. On the basis of the historical record of the polls at recent general elections, there is a 9 in 10 chance that the true value of a party’s support lies within 4 points of the estimates provided by this poll, and a 2 in 3 chance that they lie within 2 points. This is especially important to keep in mind when calculating party lead figures. 3 © Ipsos | Ipsos MORI Political Monitor | June 2021 40 50 60 10 20 30 4 % How would you vote election tomorrow? werean you wouldif there vote How Since the 2015 General Election Headline voting intention: Elections. Elections. Note small change in methodology approach in to prompting Brexit Party in 2019 July Base: 0 c. -

Survey Report

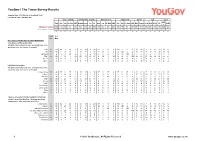

YouGov / The Times Survey Results Sample Size: 1144 Adults in Scotland (16+) Fieldwork: 2nd - 4th May 2021 Vote in 2019 GE 2016 EU Ref Indy Ref Westminster VI Holyrood VI Gender Age Social ABC Total Con Lab Lib Dem SNP Remain Leave Yes No Con Lab Lib Dem SNP Con Lab Lib Dem SNP Male Female 16-24 25-49 50-64 65+ C2DE 1 Weighted Sample 1144 213 158 81 381 588 326 431 534 187 172 43 436 179 173 56 476 551 593 150 451 285 258 595 549 Unweighted Sample 1144 231 169 85 416 612 307 398 506 194 175 46 454 188 172 58 492 519 625 136 456 291 261 626 518 % % % % % % % % % % % % % % % % % % % % % % % % % 16-20 2-4 Apr May HOLYROOD HEADLINE VOTING INTENTION Constituency Voting Intention [Weighted by likelihood to vote, excluding those who would not vote, don't know, or refused] Con 21 20 69 5 30 1 14 38 4 36 81 4 12 0 100 0 0 0 19 20 5 12 24 35 19 21 Lab 21 19 17 52 21 7 18 21 7 28 11 84 9 0 0 100 0 0 22 16 22 18 18 20 18 20 Lib Dem 6 6 5 2 40 2 6 5 2 10 5 1 75 1 0 0 100 0 7 5 4 5 5 10 7 4 SNP 49 52 7 35 7 89 60 31 83 23 2 10 3 98 0 0 0 100 49 55 63 60 52 34 52 51 Green 1 2 0 6 1 2 2 1 2 1 0 1 1 1 0 0 0 0 2 3 6 4 1 0 3 2 Other 2 1 2 1 1 0 0 3 1 1 1 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 2 0 0 2 1 1 0 2 List Voting Intention [Weighted by likelihood to vote, excluding those who would not vote, don't know, or refused] Conservative 22 22 75 6 35 1 15 44 6 40 87 9 15 0 87 14 25 1 23 22 7 14 23 41 22 23 Labour 17 16 9 46 26 5 16 15 7 22 5 74 15 1 5 71 10 2 16 15 20 11 17 19 14 17 Lib Dem 5 5 3 4 30 2 6 2 1 8 3 3 62 1 3 3 55 0 5 4 2 5 4 6 6 3 SNP 39 38 6 25 3 67 45 24 61 19 1 5 3 75 0 1 4 73 30 45 31 47 39 27 36 39 Green 10 13 1 15 4 18 14 4 18 5 0 5 5 19 0 5 5 19 17 10 35 17 9 4 16 10 UKIP 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 Reform UK 1 0 0 1 0 0 0 0 1 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 1 0 1 3 0 0 0 1 0 All for Unity 1 1 3 1 1 0 1 1 0 2 3 0 0 0 3 2 1 0 1 1 0 1 2 0 1 1 Alba 2 3 1 1 0 6 2 5 5 2 0 4 0 4 0 5 0 4 4 2 1 3 5 1 3 3 Other 2 2 2 1 1 1 1 3 1 2 1 0 0 1 1 0 1 1 3 1 0 3 1 1 1 3 There is an election to the Scottish Parliament on this Thursday, May 6th. -

EA Bulletin 296 (2021)

Having trouble reading this newsletter? View it in your browser. Contents May 2021 elections: legislation and guidance update Information on updates to guidance to reflect new legislation and the Welsh Government’s guidance on Issue 296 (Wales) – 24 March 2021 campaigning in the current May 2021 elections: legislation and guidance update public health context. We have now completed work on updating our guidance to reflect May 2021 elections: update the changes from the Welsh Elections (Coronavirus) Act 2021 on party names, (which has now received Royal Assent) and the Senedd Cymru descriptions and emblems (Representation of the People) (Amendment) Order 2021 (which came into force on 18 March). Update on recent changes to the register of political The Order amends the deadline for receipt of nominations at the parties. Senedd election to 4pm on the nineteenth day before the day of the election. The Order also amends the home address form so that a May 2021 elections: candidate who does not want their home address to be made public guidance on the can provide the Senedd constituency which their home address is management of paper located in or, if their address is outside Wales, the UK Parliamentary constituency. The home address form has been Reminder of our guidance on amended accordingly. working with or handling paper. We have also updated our supplementary guidance for campaigners to include a link to the Welsh Government’s guidance May 2021 elections: further for persons undertaking election campaigning activities in Wales call for polling station data during the Coronavirus pandemic, which covers leafleting, canvassing, collection of postal ballots and behaviour at polling Reminder of our request for stations. -

Survey Report

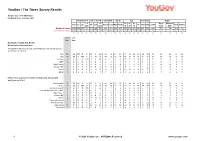

YouGov / The Times Survey Results Sample Size: 1703 GB Adults Fieldwork: 2nd - 3rd June 2021 Westminster VI Vote In 2019 GE 2016 EU Ref Gender Age Social Grade Region Lib Lib 18- 25- 50- Rest of Midlands / Total Con Lab Con Lab Remain Leave Male Female 65+ ABC1 C2DE London North Scotland Dem Dem 24 49 64 South Wales Weighted Sample 1703 527 353 73 577 422 153 632 674 828 875 186 710 410 397 971 732 204 572 370 410 146 Unweighted Sample 1703 561 379 77 593 424 159 688 705 710 993 138 661 447 457 1043 660 146 615 392 412 138 % % % % % % % % % % % % % % % % % % % % % % 27-28 2-3 May Jun HEADLINE VOTING INTENTION Westminster Voting Intention [Weighted by likelihood to vote, excluding those who would not vote, don't know, or refused] Con 43 46 100 0 0 90 4 20 26 72 47 45 11 37 49 65 44 49 34 54 47 47 24 Lab 29 30 0 100 0 3 74 26 44 13 25 34 46 38 28 17 31 28 42 24 29 38 20 Lib Dem 8 6 0 0 100 1 3 38 9 2 6 6 7 7 6 5 6 6 7 10 4 4 3 SNP 5 4 0 0 0 0 2 2 5 3 4 4 6 4 4 4 4 4 0 0 0 0 41 Plaid Cymru 1 1 0 0 0 0 2 0 1 0 2 0 7 1 1 0 1 1 0 0 4 0 3 Reform UK 3 2 0 0 0 3 0 0 0 4 4 1 5 1 3 1 1 4 4 2 4 1 0 Green 8 9 0 0 0 1 13 13 13 4 8 9 13 10 8 6 9 7 12 9 9 8 6 Other 2 2 0 0 0 2 2 1 1 3 3 2 4 2 2 2 2 2 1 3 2 2 3 If there were a general election held tomorrow, which party would you vote for? Conservative 30 31 100 0 0 76 3 14 20 53 31 31 7 22 38 51 33 28 23 38 31 30 18 Labour 20 21 0 100 0 2 59 19 35 10 17 24 29 22 22 14 24 17 28 17 19 25 16 Liberal Democrat 6 4 0 0 100 1 3 27 7 1 4 4 5 4 4 4 5 3 5 7 3 3 2 Scottish National Party (SNP) 4 3 0 0 0 0 1 1 4 2 2 3 4 2 3 3 3 2 0 0 0 0 31 Plaid Cymru 1 1 0 0 0 0 1 0 1 0 2 0 5 1 1 0 1 1 0 0 3 0 4 Reform UK 2 2 0 0 0 2 0 0 0 3 3 1 3 1 3 1 1 2 3 1 3 1 0 Green 6 6 0 0 0 1 10 10 10 3 6 6 9 6 6 5 7 4 9 6 6 5 5 Some other party 1 2 0 0 0 2 2 1 1 2 2 1 4 1 1 2 2 1 1 2 1 1 2 Would not vote 11 13 0 0 0 2 4 2 6 9 17 9 7 21 8 6 7 21 12 13 12 16 7 Don’t know 16 17 0 0 0 12 15 24 15 16 15 19 24 19 14 13 16 18 19 14 21 17 12 Refused 3 1 0 0 0 1 0 2 1 1 1 2 3 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 2 1 1 © 2021 YouGov plc.