Introduction

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Clairvoyance

No 2 | Spring 2015 | The Bartlett School of Architecture Clairvoyance Contents Reception The Seminar Room The Crit Room The Library 8 Editor’s Letter Micro Readings of Macro Conditions: 84 Jus’ Like That? 116 The Clear Sight of Words by Regner Ramos Words by Alan Penn an Architectural Historian 53 Crowds and Power Words by Stylianos Giamarelos 10 Visions With Purpose Reprinted Text by Elias Canetti 87 PoohTown Profile by Regner Ramos A Project by Nick Elias 120 The Naked Architect 55 Civic Depth Words by Gregorio Astengo 17 Pushing Forward Reprinted Text by Peter Carl 90 Fragile Thresholds Profile by HLM Architects A Project by Eliza de Silva 122 Back to the Future of Formalism! Visions of the City and the People Therein: Words by Emmanuel Petit 93 Resourceful Fallibility The Exhibition Space 57 This is Water A Project by Wangshu Zhou and Jieru Ding 123 Historico-Futurism Words by Sam Jacob in a Clockwork Jerusalem 20 Approaches to Tomorrow 96 The Sublime Words by Sam Jacob Words by Patch Dobson-Pérez 58 The Unhappy Pursuit Wilderness Institute Words by Adam Nathaniel Furman A Project by Xuhong Zheng 126 Branding Remaking 23 Future’s Tense on the Urban Scale Words by Kyle Branchesi and 59 The City Scale Narrative Words by Neli Vasileva Shane Reiner-Roth Words by Giovanni Bellotti and Alexander The Staircase Sverdlov 128 Queering Architectural History 24 One of a Libeskind 100 Reversing to the Future Words by Stylianos Giamarelos Words by Regner Ramos 60 Depth Charge Words by Ilkka Törmä Words by Patrick Lynch 130 Far From Predictions 31 -

Waiting for Redemption in the House of Asterion: a Stylistic Analysis

Open Journal of Modern Linguistics 2012. Vol.2, No.2, 51-56 Published Online June 2012 in SciRes (http://www.SciRP.org/journal/ojml) http://dx.doi.org/10.4236/ojml.2012.22007 Waiting for Redemption in The House of Asterion: A Stylistic Analysis Martin Tilney Macquarie University, Sydney, Australia Email: [email protected] Received February 20th, 2012; revised March 7th, 2012; accepted March 15th, 2012 The House of Asterion is a short story by Jorge Luis Borges that retells the classical myth of the Cretan Minotaur from an alternate perspective. The House of Asterion features the Minotaur, aka Asterion, who waits for “redemption” in his labyrinth. Many literary critics have suggested that the Borgesian labyrinth is a metaphor for human existence and the universe itself. Others have correctly interpreted Asterion’s ironic death at the hands of Theseus as his eagerly awaited redemption. Borges’ subversion of the reader’s expectations becomes the departure point for a systemic functional stylistic analysis of the story in one of its English translations, revealing how deeper-level meanings in the text are construed through its lexico- grammatical structure. A systemic functional stylistic reading suggests that on a higher level of reality, Asterion’s redemption is not only the freedom that death affords, but also a transformation that transcends his fictional universe. Asterion’s twofold redemption is brought about not only by the archetypal hero Theseus but also by the reader, who through the process of reading enables Asterion’s emancipation from the labyrinth. Keywords: The House of Asterion; Borges; Minotaur; Labyrinth; Systemic Functional; Stylistic Introduction the latter half of the twentieth century (for a detailed discussion of the difference between the terms “postmodernity” and Argentinean writer Jorge Luis Borges (1899-1986) is best “postmodernism” see Hassan, 2001). -

Postmodern Or Post-Auschwitz Borges and the Limits of Representation

Edna Aizenberg Postmodern or Post-Auschwitz Borges and the Limits of Representation he list of “firsts” is well known by now: Borges, father of the New Novel, the nouveau roman, the Boom; Borges, forerunner T of the hypertext, early magical realist, proto-deconstructionist, postmodernist pioneer. The list is well known, but it may omit the most significant encomium: Borges, founder of literature after Auschwitz, a literature that challenges our orders of knowledge through the frac- tured mirror of one of the century’s defining events. Fashions and prejudices ingrained in several critical communities have obscured Borges’s role as a passionate precursor of many later intellec- tuals -from Weisel to Blanchot, from Amery to Lyotard. This omission has hindered Borges research, preventing it from contributing to major theoretical currents and areas of inquiry. My aim is to confront this lack. I want to rub Borges and the Holocaust together in order to unset- tle critical verities, meditate on the limits of representation, foster dia- logue between disciplines -and perhaps make a few sparks fly. A shaper of the contemporary imagination, Borges serves as a touch- stone for concepts of literary reality and unreality, for problems of knowledge and representation, for critical and philosophical debates on totalizing systems and postmodern esthetics, for discussions on cen- ters and peripheries, colonialism and postcolonialism. Investigating the Holocaust in Borges can advance our broadest thinking on these ques- tions, and at the same time strengthen specific disciplines, most par- ticularly Borges scholarship, Holocaust studies, and Latin American literary criticism. It is to these disciplines that I now turn. -

Norse Mythology and Saga: Bibliography Norse Mythology

Norse Mythology and Saga: Bibliography Norse Mythology Acker, Paul, and Carolyne Larrington, eds. The Poetic Edda: Essays on Old Norse Mythology. New York: Routledge, 2002. Print. Routledge Medieval Casebooks. Anderson, Sarah M, and Karen Swenson, eds. Cold Counsel: Women in Old Norse Literature and Mythology: A Collection of Essays. New York ; London: Routledge, 2002. Print. Auden, W. H, and Paul Beekman Taylor, trans. Norse Poems. London: Athlone Press, 1981. Print. Chance, Jane, ed. Tolkien and the Invention of Myth: A Reader. Lexington: University Press of Kentucky, 2004. Print. Davidson, Hilda Roderick Ellis. Scandinavian Mythology. London ; New York: Hamlyn, 1969. Print. Jochens, Jenny. Old Norse Images of Women. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 1996. Print. Middle Ages Series. Larrington, Carolyne, tran. The Poetic Edda. Oxford ; New York: Oxford University Press, 2008. Print. Oxford World’s Classics. Lindow, John. Handbook of Norse Mythology. Santa Barbara, Calif: ABC-CLIO, 2001. Print. Handbooks of World Mythology. Tolkien, J. R. R. The Legend of Sigurd and G . Ed. Christopher Tolkien. Boston: Houghton Mifflin Harcourt, 2009. Print. Sagas Andersson, Theodore Murdock. The Growth of the Medieval Icelandic Sagas (1180-1280). Ithaca, N.Y: Cornell University Press, 2006. Print. ---. The Icelandic Family Saga; an Analytic Reading. Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1967. Print. Harvard Studies in Comparative Literature 28. Johnston, George, tran. The Saga of Gisli. London: Dent, 1973. Print. Magnusson, agnus, and Hermann P lsson, trans. Baltimore: Penguin Books, 1960. Print. Byock, Jesse L. Feud in the Icelandic Saga. Berkeley ; London: University of California Press, 1982. Print. Byock, Jesse L, and Russell Gilbert Poole, trans. G etti . -

Cambridge University Press 978-1-108-47044-5 — Jorge Luis Borges in Context Edited by Robin Fiddian Index More Information

Cambridge University Press 978-1-108-47044-5 — Jorge Luis Borges in Context Edited by Robin Fiddian Index More Information Index ‘A Rafael Cansinos Assens’ (poem), 175 Asociación Amigos del Arte, 93, 95, 97 Abramowicz, Maurice, 33, 94 Aspectos de la poesía gauchesca (essays), 79 Acevedo de Borges, Leonor (Borges’s mother), Atlas (poetry and stories), 51, 54–55, 112 26–27 28 31 32–33 254 ʿ ā ī ī , , , , At˙˙t r, Far d al-D n Adrogué (stories), 43 overview of, 222–226, 260 Aira, César, 130–131, 133–135 Conference of the Birds, The and, 219, Aleph, The (stories), 234 222–223, 225 ‘Aleph, The’ (story), 29, 30, 61, 205, 232 Auster, Paul, 7, 246 Alfonsín, Raúl, 47, 51–52 author Alighieri, Dante. See Dante collective identity of, 115, 144, 150, 168, Amorím, Enrique, 21–22 221–222, 248–249 Anglo-Saxon, 7, 32, 102, 166, 244, 246 figure of, 5, 30, 72, 232, 248 anti-Semitism, 63, 120, 143, 199. See also Nazism unique identity of, 31, 141–142, 153–154 Antología poética argentina (anthology), 118 ‘Autobiographical Essay, An’ (essay), 201, 246 ‘Approach to Al-Mu’tasim, The’ (story), 225 avant-garde Argentina Argentine, heyday of, 28, 68, 89, 92–97, centenary of, 83, 85, 95, 181 107, 183 cultural context of, 6, 96, 100, 103, 109–110, 134 Argentine, decline of, 46, 54, 117, 184, 234 desaparecidos of, 16, 46, 52, 60, 65, 111 international, 22, 94, 95, 133, 253, 261 dictatorship of, 15–16, 111–112, 117, 238, 241 Spanish, 6, 28, 92–93, 166, 173–178 language of, 13, 145, 196 tango and, 110 literary tradition of, 77–78, 99–104, 130–135 ‘Avatars of the Tortoise’ (essay), 159 national identity and, 12–13, 72–73 ‘Avelino Arredondo’ (story), 23–24 politics of, 6, 43–48, 51–56, 111–112 ‘Averroës’ Search’ (story), 215 religion and, 195–197 See also Buenos Aires; Malvinas, Islas Babel (biblical city), 12–13, 85, 206–208 ‘Argentine Writer and Tradition, The’ (essay) Banda Oriental, the, 18–24 Argentina and, 132–133, 135, 245 barbarism. -

The Enigmas of Borges, and the Enigma of Borges

THE ENIGMAS OF BORGES, AND THE ENIGMA OF BORGES Peter Gyngell, B.A. Thesis submitted to Cardiff University in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy March 2012 ii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS My thanks go to my grandson, Brad, currently a student of engineering, who made me write this thesis; to my wife, Jean, whose patience during the last four years has been inexhaustible; and to my supervisor, Dr Richard Gwyn, whose gentle guidance and encouragement have been of incalculable value. Peter Gyngell March 26, 2012 iii CONTENTS PREFACE 1 INTRODUCTION 2 PART 1: THE ENIGMAS OF BORGES CHAPTER 1: BORGES AND HUMOUR 23 CHAPTER 2: BORGES AND HIS OBSESSION WITH DEATH 85 CHAPTER 3: BORGES AND HIS PRECIOUS GIFT OF DOUBT 130 CHAPTER 4: BORGES AND HUMILITY 179 PART 2: THE ENIGMA OF BORGES CHAPTER 5: SOME LECTURES AND FICTIONS 209 CHAPTER 6: SOME ESSAYS AND REVIEWS 246 SUMMARY 282 POSTSCRIPT 291 BIBLIOGRAPHY 292 1 PREFACE A number of the quoted texts were published originally in English; I have no Spanish, and the remaining texts are quoted in translation. Where possible, translations of Borges’ fictions will be taken from The Aleph and Other Stories 1933-1969 [Borges, 1971]; they are limited in number but, because of the involvement of Borges and Norman Thomas di Giovanni, they are taken to have the greater authority; in the opinion of Emir Rodriguez Monegal, a close friend of Borges, these translations are ‘the best one can ask for’ [461]; furthermore, this book contains Borges’ ‘Autobiographical Essay’, together with his Commentaries on each story. -

The Visualizing Capacity of Magical Realism: Objects and Expression in the Work of Jorge Luis Borges

The Visualizing Capacity of Magical Realism: Objects and Expression in the Work of Jorge Luis Borges Lois Parkinson Zamora University of Houston In those days the world of mirrors and the world of men were not, as they are now, cut off from each other. —Jorge Luis Borges, “Fauna of Mirrors,” Borges and Guerrero 67 The term “magical realism” was first uttered in a discussion of the visual arts. The German art critic Franz Roh, in his 1925 essay, de- scribed a group of painters whom we now categorize generally as Post- Expressionists, and he used the term Magischer Realismus to emphasize (and celebrate) their return to figural representation after a decade or more of abstract art. In the introduction to the expanded Spanish-lan- guage version of this essay published two years later, in 1927, by José Ortega y Gasset by his Revista de Occidente, Roh again emphasized these painters’ engagement of the “everyday,” the “commonplace”: “with the word ‘magic’ as opposed to ‘mystic,’ I wish to indicate that the mystery does not descend to the represented world, but rather hides and palpi- tates behind it” (“Magical” 16). An alternative label circulating at the time for this style of German painting was Neue Sachlichkeit, New Ob- jectivity, a term that has outlived Magischer Realismus, in part because Roh eventually disavowed his own designation. In his 1958 survey of twentieth-century German art, he explicitly retired the term “magical re- 22 Lois Parkinson Zamora alism,” tying its demise to the status of the object itself: “In our day and age, questions about the character of the object … have become irrel- evant … I believe that we can demonstrate that in abstract art the greatest [achievements] are again possible” (German 10). -

The Boreal Borges

Brigham Young University BYU ScholarsArchive Theses and Dissertations 2013-05-31 The Boreal Borges Jonathan C. Williams Brigham Young University - Provo Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarsarchive.byu.edu/etd Part of the Classics Commons, and the Comparative Literature Commons BYU ScholarsArchive Citation Williams, Jonathan C., "The Boreal Borges" (2013). Theses and Dissertations. 3597. https://scholarsarchive.byu.edu/etd/3597 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by BYU ScholarsArchive. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of BYU ScholarsArchive. For more information, please contact [email protected], [email protected]. The Boreal Borges Jonathan C. Williams A thesis submitted to the faculty of Brigham Young University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts Steven Sondrup, Chair David Laraway Larry Peer Department of Humanities, Classics, and Comparative Literature Brigham Young University June 2013 Copyright © 2013 Jonathan C. Williams All Rights Reserved ABSTRACT The Boreal Borges Jonathan C. Williams Department of Humanities, Classics, and Comparative Literature, BYU Master of Arts Jorge Luis Borges’s story “El Zahir” describes a moment where the protagonist finds rest from his monomania by reworking one of the central texts in Old Germanic myth, the story of Sigurd and Brynhild. The approach taken here by the protagonist is the paradigm used in this thesis for understanding Borges’s own strong readings of Old Germanic literature, specifically Old Scandinavian texts. In chapter one, a brief outline of the myth of Sigurd and Brynhild, with a particular emphasis on Gram, the sword that lied between them, is provided and juxtaposed with Borges’s own family history, focusing on the family’s storied military past. -

Laboratorio Dell'immaginario IL SEGRETO

laboratorio dell’immaginario issn 1826-6118 rivista elettronica http://cav.unibg.it/elephant_castle IL SEGRETO a cura di Raul Calzoni, Michela Gardini, Viola Parente-Čapková settembre 2019 CAV - Centro Arti Visive Università degli Studi di Bergamo ADAM CHAMBERS A Secret Demand: On Endless Forms of Fiction in Borges’ El Milagro Secreto …the edges of a secret are more secret than the secret itself. – Maurice Blanchot (2003: 188). It is possible that in every work, language is superimposed upon itself in a secret verticality… – Michel Foucault (1977: 57). Although Jorge Luis Borges’ writings are often revered as master- works of twentieth-century fiction, his stories, or ficciones, still sit uncomfortably within the literary cannon. While they are often grouped within specific literary movements, such as modernist and postmodernist fiction, they also remain largely elusive to their read- ers, and resist any clear understanding.1 In particular, one can argue that through their many contradictions, perplexing details, and con- densed narratives, the Argentine author’s works are in fact, unclassi- fiable; not bound to a single national literature, they also fail to unite their readers around a set of recognizable literary forms.2 1 The debate regarding where to place Borges’ works in literary history is ongo- ing. He has been described as both a late modernist, and an early postmodernist. For example, see Javier Cercas’ recent study, The Blind Spot: An Essay on the Novel, for a discussion of how in literature, “postmodernity begins with Borges” (2018: 31). Alternately, for a strong endorsement of Borges as a modernist writer, see Sylvia Molloy’s “Mimesis and Modernism: The Case of Jorge Luis Borges,” in the edited collection, Literary Philosophers: Borges, Calvino, Eco (2002: 109). -

August 18, 2012 Meeting 1:45-2:45 Joshua Corin, Whose Thriller

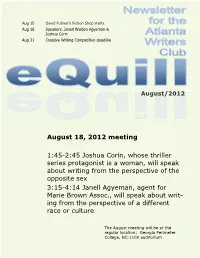

Aug 15 David Fulmer’s Fiction Shop starts Aug 18 Speakers: Janell Walden Agyeman & Joshua Corin Aug 31 Creative Writing Competition deadline August/2012 August 18, 2012 meeting 1:45-2:45 Joshua Corin, whose thriller series protagonist is a woman, will speak about writing from the perspective of the opposite sex 3:15-4:14 Janell Agyeman, agent for Marie Brown Assoc., will speak about writ- ing from the perspective of a different race or culture The August meeting will be at the regular location: Georgia Perimeter College, NC-1100 auditorium ...founded in 1914 We are a social and educational club where local writers meet to discuss the craft and business of writing. We also sponsor contests for our members and host expert speakers from the worlds of writing, publishing, and entertainment. Inside this Edition Officers In Context 3 President: American Literately Merit Award 5 Clay Ramsey August Speakers 6 Officer Emeritus: Class for Fledgling Writers 7 George Weinstein Support Your Library 8 Membership VP: Atlanta Story Development Private Workshop 9 Ginny Bailey Authors’ Reception 10 Programs VP: Books for Heroes 11 Anjali Enjeti-Sydow Texas Review Press Breakthrough Poetry Prize 11 Soniah Kamal Prep Workshop for Manuscripts Critiques 12 Secretary: Loretta Hannon Presents 13 Bill Black Spring Contest Winners 14 Treasurer: Atlanta Writers Conference 15 Kimberly Ciamarra Book Your Success 16 Creative Writing Competition 17 Operations VP: Workshop Photos 18 Valerie Connors Seeking Manuscripts 19 Contests, Awards, Writing Contest 20 Scholarships VP: Moonlight & Magnolias 21 Nedra Roberts Fall AWC Contest Guidelines 23 Marketing/PR VP: Looking Ahead 26 Tara Lynne Groth Critique Groups 27 Social Director: Membership Information 28 Cindy Wiedenbeck Membership Form 29 Volunteers: Historian/By- Laws: Adrian Drost It's time again to call on our members for support, and ask for volunteers to help out with some of the many exciting programs heading our way in the coming months. -

000000827.Sbu.Pdf (597.6Kb)

SSStttooonnnyyy BBBrrrooooookkk UUUnnniiivvveeerrrsssiiitttyyy The official electronic file of this thesis or dissertation is maintained by the University Libraries on behalf of The Graduate School at Stony Brook University. ©©© AAAllllll RRRiiiggghhhtttsss RRReeessseeerrrvvveeeddd bbbyyy AAAuuuttthhhooorrr... Reading, Borges In Search of Lost Eternity A Thesis Presented by Isaac Fer To The Graduate School In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts In Philosophy Stony Brook University December 2009 Stony Brook University The Graduate School Isaac Fer We, the thesis committee for the above candidate for the Master of Arts, hereby recommend acceptance of this thesis. Hugh J. Silverman—Thesis Advisor Professor of Philosophy and Comparative Literary and Cultural Studies Department of Philosophy Robert Crease—Second Reader Professor of Philosophy and Chairman Department of Philosophy This thesis is accepted by the Graduate School Lawrence Martin Dean of the Graduate School ii Abstract of the Thesis Reading, Borges: In Search of Lost Eternity By Isaac Fer Master of Arts in Philosophy Stony Brook University 2009 Jorge Luis Borges repeatedly suggests that the history of metaphysics is a “history of perplexities.” In the introduction, I briefly explicate this notion by suggesting that there are mysteries that characterize the human condition. In each successive section, I examine the influence these “perplexities” have on Borges’ work. The primary enigma that motivates Borges’ writing, I suggest, is the one between temporality and eternity—that humankind is imprisoned by temporality and yet dreams of the ecstatic heights of the eternal absolute. We then locate in the first section this paradoxical possibility within the use of metaphor and allegory to make present for the reader certain eternal forms. -

Foucault's Heterotopia in the Fiction of James Joyce, Vladimir Nabokov

Real Places and Impossible Spaces: Foucault’s Heterotopia in the Fiction of James Joyce, Vladimir Nabokov, and W.G. Sebald Kelvin Knight Thesis submitted for the qualification of Doctor of Philosophy University of East Anglia School of Literature, Drama and Creative Writing February 2014 This copy of the thesis has been supplied on condition that anyone who consults it is understood to recognise that its copyright rests with the author and that use of any information derived there from must be in accordance with current UK Copyright Law. In addition, any quotation or extract must include full attribution. Abstract This thesis looks to restore Michel Foucault’s concept of the heterotopia to its literary origins, and to examine its changing status as a literary motif through the course of twentieth-century fiction. Initially described as an impossible space, representable only in language, the term has found a wider audience in its definition as a kind of real place that exists outside of all other space. Examples of these semi- mythical sites include the prison, the theatre, the garden, the library, the museum, the brothel, the ship, and the mirror. Here, however, I argue that the heterotopia was never intended as a tool for the study of real urban places, but rather pertains to fictional representations of these sites, which allow authors to open up unthinkable configurations of space. Specifically, I focus on three writers whose work contains numerous examples of these places, and who shared the circumstance of spending the majority of their lives in exile: James Joyce, Vladimir Nabokov, and W.G.