The Visualizing Capacity of Magical Realism: Objects and Expression in the Work of Jorge Luis Borges

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Crimson Hexagon. Books Borges Never Wrote

Allen Ruch The Crimson Hexagon Books Borges Never Wrote “The composition of vast books is a laborious and impoverish- ing extravagance. To go on for five hundred pages developing an idea whose perfect oral exposition is possible in a few min- utes! A better course of procedure is to pretend that these books already exist, and then to offer a resume, a commen- tary… More reasonable, more inept, more indolent, I have preferred to write notes upon imaginary books.” (Jorge Luis Borges). he fiction of Borges is filled with references to encyclopedias that do not exist, reviews of imaginary books by fictional au- T thors, and citations from monographs that have as much real existence as does the Necronomicon or the Books of Bokonon. As an intellectual exercise of pure whimsical uselessness, I have cata- logued here all these “imaginary” books that I could find in the stories of the “real” Argentine. I am sure that Borges himself would fail to see much of a difference… Note: In order to flesh out some of the details, I have elaborated a bit - although much of the detail on these books is really from Borges. I have added some dates, some information on contents, and a few general descriptions of the book’s binding and cover; I would be more than happy to accept other submissions and ideas on how to flesh this out. Do you have an idea I could use? The books are arranged alphabetically by author. Variaciones Borges 1/1996 122 Allen Ruch A First Encyclopaedia of Tlön (1824-1914) The 40 volumes of this work are rare to the point of being semi- mythical. -

Time, Infinity, Recursion, and Liminality in the Writings of Jorge Luis Borges

Kevin Wilson Of Stones and Tigers; Time, Infinity, Recursion, and Liminality in the writings of Jorge Luis Borges (1899-1986) and Pu Songling (1640-1715) (draft) The need to meet stones with tigers speaks to a subtlety, and to an experience, unique to literary and conceptual analysis. Perhaps the meeting appears as much natural, even familiar, as it does curious or unexpected, and the same might be said of meeting Pu Songling (1640-1715) with Jorge Luis Borges (1899-1986), a dialogue that reveals itself as much in these authors’ shared artistic and ideational concerns as in historical incident, most notably Borges’ interest in and attested admiration for Pu’s work. To speak of stones and tigers in these authors’ works is to trace interwoven contrapuntal (i.e., fugal) themes central to their composition, in particular the mutually constitutive themes of time, infinity, dreaming, recursion, literature, and liminality. To engage with these themes, let alone analyze them, presupposes, incredibly, a certain arcane facility in navigating the conceptual folds of infinity, in conceiving a space that appears, impossibly, at once both inconceivable and also quintessentially conceptual. Given, then, the difficulties at hand, let the following notes, this solitary episode in tracing the endlessly perplexing contrapuntal forms that life and life-like substances embody, double as a practical exercise in developing and strengthening dynamic “methodologies of the infinite.” The combination, broadly conceived, of stones and tigers figures prominently in -

Dragonlore Issue 37 08-11-03

The bird was a Rukh and the white dome, of course, was its egg. Sindbad lashes himself to the bird’s leg with his turban, and the next morning is whisked off into flight and set down on a mountaintop, without having excited the Rukh’s attention. The narrator adds that the Rukh feeds itself on serpents of such great bulk that they would have made but one gulp of an elephant. In Marco Polo’s Travels (III, 36) we read: Dragonlore The people of the island [of Madagascar] report that at a certain season of the year, an extraordinary kind of bird, which they call a rukh, makes its appearance from The Journal of The College of Dracology the southern region. In form it is said to resemble the eagle but it is incomparably greater in size; being so large and strong as to seize an elephant with its talons, and to lift it into the air, from whence it lets it fall to the ground, in order that when dead it Number 37 Michaelmas 2003 may prey upon the carcase. Persons who have seen this bird assert that when the wings are spread they measure sixteen paces in extent, from point to point; and that the feathers are eight paces in length, and thick in proportion. Marco Polo adds that some envoys from China brought the feather of a Rukh back to the Grand Kahn. A Persian illustration in Lane shows the Rukh bearing off three elephants in beak and talons; ‘with the proportion of a hawk and field mice’, Burton notes. -

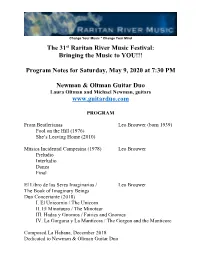

Program Notes for Saturday, May 9, 2020 at 7:30 PM Newman

Change Your Music * Change Your Mind The 31st Raritan River Music Festival: Bringing the Music to YOU!!! Program Notes for Saturday, May 9, 2020 at 7:30 PM Newman & Oltman Guitar Duo Laura Oltman and Michael Newman, guitars www.guitarduo.com PROGRAM From Beatlerianas Leo Brouwer (born 1939) Fool on the Hill (1976) She’s Leaving Home (2010) Música Incidental Campesina (1978) Leo Brouwer Preludio Interludio Danza Final El Libro de los Seres Imaginarios / Leo Brouwer The Book of Imaginary Beings Duo Concertante (2018) I. El Unicornio / The Unicorn II. El Minotauro / The Minotaur III. Hadas y Gnomos / Fairies and Gnomes IV. La Gorgona y La Mantícora / The Gorgon and the Manticore Composed La Habana, December 2018 Dedicated to Newman & Oltman Guitar Duo Commissioned by Raritan River Music With the generous support of Jeffrey Nissim CYBERSPACE PERMIERE PERFORMANCE Composed in celebration of the 80th Anniversary Year of Leo Brouwer NOTES IN ENGLISH CAPTURING THE IMAGINARY BEINGS BY LAURA OLTMAN AND MICHAEL NEWMAN The guitar explosion in the United States in the 1960s was fueled by the influence of Cuban musicians, including the legendary Leo Brouwer, as well as Juan Mercadal, Elías Barreiro, Mario Abril, and our teachers Alberto Valdes Blain and Luisa Sánchez de Fuentes. We grew up playing the music of Leo Brouwer. In the early days of the Newman & Oltman Guitar Duo, we shared a booking agent with Brouwer, Sheldon Soffer Management. We often thought that a major duet by Maestro Brouwer would be a dream for our duo. We met Brouwer at his New York debut recital in 1978, which was co- sponsored by Americas Society. -

Postmodern Or Post-Auschwitz Borges and the Limits of Representation

Edna Aizenberg Postmodern or Post-Auschwitz Borges and the Limits of Representation he list of “firsts” is well known by now: Borges, father of the New Novel, the nouveau roman, the Boom; Borges, forerunner T of the hypertext, early magical realist, proto-deconstructionist, postmodernist pioneer. The list is well known, but it may omit the most significant encomium: Borges, founder of literature after Auschwitz, a literature that challenges our orders of knowledge through the frac- tured mirror of one of the century’s defining events. Fashions and prejudices ingrained in several critical communities have obscured Borges’s role as a passionate precursor of many later intellec- tuals -from Weisel to Blanchot, from Amery to Lyotard. This omission has hindered Borges research, preventing it from contributing to major theoretical currents and areas of inquiry. My aim is to confront this lack. I want to rub Borges and the Holocaust together in order to unset- tle critical verities, meditate on the limits of representation, foster dia- logue between disciplines -and perhaps make a few sparks fly. A shaper of the contemporary imagination, Borges serves as a touch- stone for concepts of literary reality and unreality, for problems of knowledge and representation, for critical and philosophical debates on totalizing systems and postmodern esthetics, for discussions on cen- ters and peripheries, colonialism and postcolonialism. Investigating the Holocaust in Borges can advance our broadest thinking on these ques- tions, and at the same time strengthen specific disciplines, most par- ticularly Borges scholarship, Holocaust studies, and Latin American literary criticism. It is to these disciplines that I now turn. -

Valeria Maggiore FANTASTIC MORPHOLOGIES: ANIMAL FORM

THAUMÀZEIN 8, 2020 Valeria Maggiore FANTASTIC MORPHOLOGIES: ANIMAL FORM BETWEEN MYTHOLOGY AND EVO-DEVO Table of Contents: 1. Imaginary beings and the rules of form; 2. The hundred eyes of Argos: Evo-Devo, evolutionary plasticity and historical constraints; 3. The wings of Pegasus: architectural constraints and mor- phospace; 4. Conclusions: from imaginary beings to fantastic beings. Perhaps universal history is the history of a few metaphors. J.L. Borges, Pascal’s Sphere, 1952. 1. Imaginary beings and the rules of form «It is the animal with the big tail, a tail many yards long and like a fox’s brush. How I should like to get my hands on this tail sometime, but it is impossible, the animal is constantly moving about, the tail is constantly being flung this way and that. The animal resembles a kangaroo, but not as to the face, which is flat almost like a human face, and small and oval; only its teeth have any power of expression, whether they are concealed or bared» [Borges 1974, 17]. With these words Franz Kafka describes a bizarre creature that appeared in his dreams: a hybrid in which the perspicuous characters of morphologically and ethologically different animals – such as the fox and the kangaroo – are mixed to human somatic traits, recalling ancient mythological beings [Borghese 2009, 283]. Jorge Luis Borges accurately transcribes the words of the Prague writer in his Book of Imaginary Beings [Borges 1974], a manual of fan- tastic zoology written in collaboration with María Guerrero in 1957 and 39 Valeria Maggiore inscribed in the literary tradition of medieval bestiaries. -

The Significant Other: a Literary History of Elves

1616796596 The Significant Other: a Literary History of Elves By Jenni Bergman Thesis submitted for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Cardiff School of English, Communication and Philosophy Cardiff University 2011 UMI Number: U516593 All rights reserved INFORMATION TO ALL USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. In the unlikely event that the author did not send a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. Dissertation Publishing UMI U516593 Published by ProQuest LLC 2013. Copyright in the Dissertation held by the Author. Microform Edition © ProQuest LLC. All rights reserved. This work is protected against unauthorized copying under Title 17, United States Code. ProQuest LLC 789 East Eisenhower Parkway P.O. Box 1346 Ann Arbor, Ml 48106-1346 DECLARATION This work has not previously been accepted in substance for any degree and is not concurrently submitted on candidature for any degree. Signed .(candidate) Date. STATEMENT 1 This thesis is being submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of PhD. (candidate) Date. STATEMENT 2 This thesis is the result of my own independent work/investigation, except where otherwise stated. Other sources are acknowledged by explicit references. Signed. (candidate) Date. 3/A W/ STATEMENT 3 I hereby give consent for my thesis, if accepted, to be available for photocopying and for inter-library loan, and for the title and summary to be made available to outside organisations. Signed (candidate) Date. STATEMENT 4 - BAR ON ACCESS APPROVED I hereby give consent for my thesis, if accepted, to be available for photocopying and for inter-library loan after expiry of a bar on accessapproved bv the Graduate Development Committee. -

Hyper Memory, Synaesthesia, Savants Luria and Borges Revisited

Dement Neuropsychol 2018 June;12(2):101-104 Views & Reviews http://dx.doi.org/10.1590/1980-57642018dn12-020001 Hyper memory, synaesthesia, savants Luria and Borges revisited Luis Fornazzari1, Melissa Leggieri2, Tom A. Schweizer3, Raul L. Arizaga4, Ricardo F. Allegri5, Corinne E. Fischer6 ABSTRACT. In this paper, we investigated two subjects with superior memory, or hyper memory: Solomon Shereshevsky, who was followed clinically for years by A. R. Luria, and Funes the Memorious, a fictional character created by J. L. Borges. The subjects possessed hyper memory, synaesthesia and symptoms of what we now call autistic spectrum disorder (ASD). We will discuss interactions of these characteristics and their possible role in hyper memory. Our study suggests that the hyper memory in our synaesthetes may have been due to their ASD-savant syndrome characteristics. However, this talent was markedly diminished by their severe deficit in categorization, abstraction and metaphorical functions. As investigated by previous studies, we suggest that there is altered connectivity between the medial temporal lobe and its connections to the prefrontal cingulate and amygdala, either due to lack of specific neurons or to a more general neuronal dysfunction. Key words: memory, hyper memory, savantism, synaesthesia, autistic spectrum disorder, Solomon Shereshevsky, Funes the memorious. HIPERMEMÓRIA, SINESTESIA, SAVANTS: LURIA E BORGES REVISITADOS RESUMO. Neste artigo, investigamos dois sujeitos com memória superior ou hipermemória: Solomon Shereshevsky, que foi seguido clinicamente por anos por A. R. Luria, e Funes o memorioso, um personagem fictício criado por J. L. Borges. Os sujeitos possuem hipermemória, sinestesia e sintomas do que hoje chamamos de transtorno do espectro autista (TEA). -

The Book of Imaginary Beings Program Notes

The Book of Imaginary Beings is inspired by Jorge Luis Borges’ encyclopedia of fantastic zoology of the same name. I. The Monster Acheron Only one man ever saw the monster Acheron, and that, but a single time. Acheron was larger than a mountain. Its eyes shot forth flames and its mouth was so enormous that nine thousand men would fit inside. Two of the condemned, like pillars or caryatids, held the monster’s jaws open; one was upright, the other upside-down. The beast had three gullets; all vomited forth inextinguishable fire. From the beast’s belly there issued the constant lamentations of the numberless condemned who had been devoured. Inside the monster [were] found tears, fog and mist, the cracking and crushing sound of teeth, fire, an unbearable burning sensation, a glacial cold, dogs, bears, lions, and snakes. In this legend, Hell is an animal with other animals inside it. II. Sirens I have seen them riding seaward on the waves Combing the white hair of the waves blown back When the wind blows the water white and black We have lingered in the chambers of the sea By sea-girls wreathed with seaweed red and brown Till human voices wake us and we drown. - T. S. Eliot, The Love Song of J. Alfred Prufrock III. The Squonk Few people outside of Pennsylvania have ever heard of this quaint beast, which is said to be fairly common in the hemlock forests of that state. The Squonk is of a very retiring disposition, generally traveling about at twilight and dusk. -

Argentina's Right to Be Forgotten

Emory International Law Review Volume 27 Issue 1 2013 Argentina's Right to be Forgotten Edward L. Carter Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarlycommons.law.emory.edu/eilr Recommended Citation Edward L. Carter, Argentina's Right to be Forgotten, 27 Emory Int'l L. Rev. 23 (2013). Available at: https://scholarlycommons.law.emory.edu/eilr/vol27/iss1/3 This Recent Development is brought to you for free and open access by the Journals at Emory Law Scholarly Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Emory International Law Review by an authorized editor of Emory Law Scholarly Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. CARTER GALLEYSFINAL 6/19/2013 11:44 AM ARGENTINA’S RIGHT TO BE FORGOTTEN ∗ Edward L. Carter INTRODUCTION The twentieth century Argentine author Jorge Luis Borges wrote a fictional short story about a boy named Ireneo Funes who suffered the curse of remembering everything.1 For Funes, the present was worthless because it was consumed by his memories of the past. One contemporary author has described the lesson of Funes: “Borges suggests that forgetting—that is, forgetting ceaselessly—is essential and necessary for thought and language and literature, for simply being a human being.”2 The struggle between remembering and forgetting is not unique to Borges or Argentina, but that struggle has manifested itself in Argentina in poignant ways, even outside the writings of Borges. In recent years, the battle has played out in Argentina’s courts in the form of lawsuits by celebrities against the Internet search engines Google and Yahoo. -

Paulo Coelho

PAULO COELHO The Zahir A NOVEL OF OBSESSION Translated from the Portuguese by Margaret Jull Costa O Mary, conceived without sin, pray for us who turn to you. Amen ABOUT THE AUTHOR Born in Brazil, PAULO COELHO is one of the most beloved writers of our time, renowned for his international bestseller The Alchemist . His books have been translated into 59 languages and published in 150 countries. He is also the recipient of numerous prestigious international awards, among them the Crystal Award by the World Economic Forum, France’s Chevalier de l’Ordre National de la Légion d’Honneur, and Germany’s Bambi 2001 Award. He was inducted into the Brazilian Academy of Letters in 2002. Mr. Coelho writes a weekly column syndicated throughout the world. Visit www.AuthorTracker.com for exclusive information on your favorite HarperCollins author. ALSO BY PAULO COELHO The Alchemist The Pilgrimage The Valkyries By the River Piedra I Sat Down and Wept The Fifth Mountain Veronika Decides to Die Warrior of the Light: A Manual Eleven Minutes CREDITS Photograph of mountains © Romilly Lockyer / Getty Images Photograph of woman © Superstock Copyright THE ZAHIR: A NOVEL OF OBSESSION. Copyright © 2005 by Paulo Coelho. English translation copyright © 2005 Margaret Jull Costa. All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. By payment of the required fees, you have been granted the non-exclusive, non-transferable right to access and read the text of this e-book on-screen. No part of this text may be reproduced, transmitted, down-loaded, decompiled, reverse engineered, or stored in or introduced into any information storage and retrieval system, in any form or by any means, whether electronic or mechanical, now known or hereinafter invented, without the express written permission of PerfectBound™. -

The Zahir by Jorge Luis Borges

The Zahir By Jorge Luis Borges My friend Borges once described a Zahir, which in Buenos Aires in 1939 was a coin, a ten-centavo piece, with the letters ‘N’ and ‘T’ and the numeral ‘2’ scratched crudely in the obverse. Whomsoever saw this coin was consumed by it, in a manner of speaking, and could think of nothing else, until at last their personality ceased to exist, and they were reduced to a babbling corpse with nothing to talk about but the coin, the coin, always the coin. To have one’s mind devoured by coins, that is a terrible fate, although one which is common enough in these mercenary times. But to have one’s mind devoured by the thought of a coin, that is strange and far more terrible. With such stories as these Borges kept me awake at night, to keep him company when he could not sleep. I had arrived in Uruguay on a tramp steamer from Cuba and had tried to work my way down the country to the Argentina, where I would stay with Borges. But my money was nearly exhausted when I reached the Fray Bentos and I used the last of it to send a message to Borges, begging him to come help me. But he was detained by the press of his librarianship, and could not take enough time off at such short notice to come and get me. And so it happened that I lived for two weeks in a small town in Argentina with an insane cripple named Ireneo Funes.