Knights, Memory, and the Siege of 1565: an Exhibition on the 450Th Anniversary of the Great Siege of Malta

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Download the Fortifications of Malta 1530-1945 Free Ebook

THE FORTIFICATIONS OF MALTA 1530-1945 DOWNLOAD FREE BOOK Charles Stephensen, Steve Noon | 64 pages | 01 Feb 2004 | Bloomsbury Publishing PLC | 9781841766935 | English | United Kingdom Welcome to the Noble Knight Games eBay Store! I expect more from an Osprey book. Pembroke Local Council in Maltese. Construction of the batteries began in and they were complete by The first fortifications in Malta were built during the Bronze Age. The last coastal watchtower to be built was Sopu Towerwhich was constructed in Gozo in Item location:. Have one to sell? It is located in a building adjoining Saint Andrew's Bastion, part of the city walls of Valletta. Make sure to view all the different shipping options we The Fortifications of Malta 1530-1945 available to save even further! Archived from the original on 4 April Email to friends Share on Facebook - opens in a new window or tab Share on Twitter - opens in a The Fortifications of Malta 1530-1945 window or tab Share on Pinterest - opens in a new window or tab Add to Watchlist. However, since the beginning of the 21st century, a number of fortifications have been restored or are undergoing restoration. Ecumenism: A Guide for the Perplexed. Shane Jenkins rated it really liked it May 16, Goodreads helps you keep track of books you want to read. To see what your friends thought of this book, please sign up. You may combine The Fortifications of Malta 1530-1945 to save on shipping costs. Victor rated it really liked it May 19, British Period. He's had a life-long passion for illustration, and since has worked as a professional artist. -

Fireworks of Music in Malta

MAY No 5 (13) 2018 New stars: Malta International Piano Competition 2018 Armenian Cultural Days fireworks MIMF of music 2018: in Malta CONTENTS MIMF — 2018 A new circle VI Malta International of the “culture circulation”… ................... 48 Music Festival in all dimensions ................ 4 The way youngsters do ............................ 50 What people say about the VI Malta International Music Festival ......... 5 Ephemerides and other ephemeral bodies ........................... 52 New stars: Malta International ......................... Piano Competition 2018 ........................... 10 Bravo, maestro Accardo! 54 Tchaikovsky, Elgar, Shor PERSON Alexey Shor: and Chagall for the unenl ightened “I liked the energy and the most sophisticated... .................. 56 of Armenian audience” ............................. 12 Captivating reading of sound .................. 58 Alexander Sokolov: “ The main criterion for a member ARMENIAN DAYS IN MALTA Unforgettable Armenian of the jury is whether you want to listen Cultural Days in sunny Malta .................... 60 to this composer again” ........................... 14 “We managed to find a common Carmine Lauri: language very quickly, and “Give me a tune and I am happy!” ............. 16 we worked together easily” .................... 63 Krzysztof Penderecki: “Maestro Sergey Smbatyan Anna Ter-Hovakimyan: Critics and musicologists keeps surprising me with his talent” ....... 20 hail performance of Symphony Georges Pélétsis: Orchestra in Malta .................................... 64 -

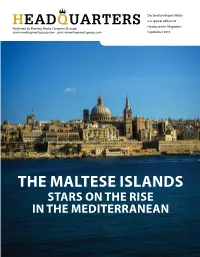

The Maltese Islands Stars on the Rise in the Mediterranean > Introduction

Destination Report Malta HEADQUARTERS is a special edition of Headquarters Magazine - Published by Meeting Media Company (Europe) www.meetingmediagroup.com - [email protected] September 2015 THE MALTESE ISLANDS STARS ON THE RISE IN THE MEDITERRANEAN > Introduction Vella Clive THE MALTESE ISLANDS: © MALTA, GOZO AND COMINO A Rising Meetings Destination in the Mediterranean The Three Cities and the Grand Harbour Malta may be one of the smallest countries in Europe, but it also boasts quite a dynamic history spanning 7,000 years of rule and conquest passing from the Romans, Knights of the Order of St. John and Napoleon to the English in more recent times. Almost everywhere you look on the Maltese archipelago you’ll find remnants of the islands’ past, from the Megalithic temples to the Baroque churches and palaces constructed by the knights. With the ability to transform almost any historic site into a stunning venue, it’s no surprise Malta is capitalizing on its culture and emerging as one of the top new meeting destinations in the Mediterranean. Report Lane Nieset Located in the middle of the Mediterranean capital of Mdina and you’re instantly trans- important characteristic in our daily lives. We between Sicily and northern Africa, the ported back in time to a fortified city that’s also share a culture of discipline which was Maltese archipelago includes the three maintained the same narrow winding streets brought about by the influence of the British inhabited islands of Malta, Gozo and Comino. it had 1,000 years ago. rule which lasted 150 years. Whilst our history It’s believed that humans first made their way has influenced and shaped considerably our to Malta in 5,000 B.C., crossing a land bridge Gozo, meanwhile, is just a 25-minute culture, we are also Mediterranean but most connected to Sicily. -

Bulletin – No 123- Nov. 2017

The Bulletin Malta Priory Order of St. John of Jerusalem Knights Hospitaller Russian Grand Priory - Malta Under the Constitution of His Late Majesty King Peter II of Yugoslavia R Nos.52875-528576 No. 123 2017-1 A message from the Grand Commander & Grand Prior of the Russian Grand Priory of Malta, Bailiff Paul M. Borg OSJ Since my installation as Grand Commander in December 2002, the Order of St. John of Jerusalem, Knights Hospitaller, its Administrative Arm and its International Headquarters itself have all undergone great changes. New members - Knights and Dames - have been invested into the Order while a few have, on the other hand, lost interest and resigned. Others have even been expelled from the Order. Apart from the then existing Priories that have increased the number of Commanderies and the number of members, new Priories and new Commanderies have sprouted in other parts of the globe so as to be added to the ones that had already existed. The International Headquarters was in a grievous state and had to undergo and is still undergoing an overall refurbishment. All these activities had to be dealt with ‘on the spur of the moment’ with great difficulty and hardship. Had it not been for the donations and voluntary work given by some of our Knights/Dames and other members of the Order, all this could not have been possible to achieve. This voluminous amount of work did not stop – nor did it slow down – the Council from keeping the Malta Priory able to uphold its main aim, namely that of continuing to live up to the motto of the Order ‘Pro Fide, Pro Utilitate Hominum’ thus at all times being prompt in its generosity in the giving of donations to those who truly are in need. -

Caravaggio, Second Revised Edition

CARAVAGGIO second revised edition John T. Spike with the assistance of Michèle K. Spike cd-rom catalogue Note to the Reader 2 Abbreviations 3 How to Use this CD-ROM 3 Autograph Works 6 Other Works Attributed 412 Lost Works 452 Bibliography 510 Exhibition Catalogues 607 Copyright Notice 624 abbeville press publishers new york london Note to the Reader This CD-ROM contains searchable catalogues of all of the known paintings of Caravaggio, including attributed and lost works. In the autograph works are included all paintings which on documentary or stylistic evidence appear to be by, or partly by, the hand of Caravaggio. The attributed works include all paintings that have been associated with Caravaggio’s name in critical writings but which, in the opinion of the present writer, cannot be fully accepted as his, and those of uncertain attribution which he has not been able to examine personally. Some works listed here as copies are regarded as autograph by other authorities. Lost works, whose catalogue numbers are preceded by “L,” are paintings whose current whereabouts are unknown which are ascribed to Caravaggio in seventeenth-century documents, inventories, and in other sources. The catalogue of lost works describes a wide variety of material, including paintings considered copies of lost originals. Entries for untraced paintings include the city where they were identified in either a seventeenth-century source or inventory (“Inv.”). Most of the inventories have been published in the Getty Provenance Index, Los Angeles. Provenance, documents and sources, inventories and selective bibliographies are provided for the paintings by, after, and attributed to Caravaggio. -

NEWSLETTER 162 April 2017

THE MALTESE E-NEWSLETTER 162 April 2017 In accordance with long-standing tradition in Malta, the High Commission will hold a commemorative and wreath-laying ceremony on Anzac Day at Pieta Military Cemetery , commencing at 10.30am on Tuesday, 25 April 2017. The event will be co-hosted by the Australian High Commission and the New Zealand Honorary Consulate. On this occasion the President, H.E. Mrs Marie Louise Coleiro Preca, will be in attendance to represent the Government of Malta at the ceremony, we anticipate there will also be a number of VIPs and members of the Diplomatic Corps who will attend the ceremony. The general public is welcome to attend. Queries can be directed to Sofia Galvan, (+356) 2133 8201 ext. 107 or at [email protected] The commemoration will run quite similarly to the event held last year ANZAC DAY CEREMONY AT PIETA CEMETERY MALTA 1 THE MALTESE E-NEWSLETTER 162 April 2017 This month in history: Malta's George Cross – 15 April 1942 ‘To honour the brave people’ On 15 April 1942, King George VI awarded the people of Malta the George Cross in recognition of their continuing and heroic struggle against repeated and continuous attacks during World War 2. Malta was the first British Commonwealth country to receive the bravery award, which is usually given to individuals, and is second only in rank to the Victoria Cross. The George Cross was 'intended primarily for civilians and award in Our military services is to be confined to actions for which purely military Honours are not normally granted.' Why was Malta so crucial to both the Allies and Axis? The island was of vital strategic importance for the Allies to sustain their North African campaign, being situated between Italy and North Africa. -

Barry Lawrence Ruderman Antique Maps Inc

Barry Lawrence Ruderman Antique Maps Inc. 7407 La Jolla Boulevard www.raremaps.com (858) 551-8500 La Jolla, CA 92037 [email protected] [Hand Drawn Map of Valletta] Les Villes, Forts, et Chateaux de Malte 1724 Stock#: 62069op Map Maker: Anonymous Date: 1724 circa Place: n.p. Color: Pen & Ink Condition: VG+ Size: 14 x 8.5 inches Price: SOLD Description: Manuscript Map from 1724 Finely executed hand-drawn map of Valletta and environs, with nomenclature in French, illustrating the town, fortifications and neighboring fortifications. The map is oriented with southwest at the top. Among the fortified areas to the left of Malta are: Port du Sangle ou des Francois Port Des Galeres / Chateau St. Anoe Le Bourg / Port du Bourg ou des Anglois Port de la Renelle Includes an elaborate compass rose. Valletta The peninsula which is now Valletta was previously called Xagħret Mewwija, named during the Arab period. Mewwija refers to a sheltered place. The extreme end of the peninsula was known as Xebb ir-Ras (Sheb point), of which name origins from the lighthouse on site. A family which surely owned land became known as Sceberras, now a Maltese surname as Sciberras. At one point the entire peninsula became known as Sceberras. The building of a city on the Sciberras Peninsula was proposed by the Order of Saint John as early as 1524, a time when the only building on the peninsula was a small watchtower dedicated to Erasmus of Drawer Ref: Italy South Stock#: 62069op Page 1 of 2 Barry Lawrence Ruderman Antique Maps Inc. 7407 La Jolla Boulevard www.raremaps.com (858) 551-8500 La Jolla, CA 92037 [email protected] [Hand Drawn Map of Valletta] Les Villes, Forts, et Chateaux de Malte 1724 Formia (Saint Elmo), which had been built in 1488. -

History of Malta Under the Order of Saint John - Wikipedia

6/23/2020 History of Malta under the Order of Saint John - Wikipedia History of Malta under the Order of Saint John Malta was ruled by the Order of Saint John as a vassal state of the Kingdom of Sicily from 1530 to 1798. The islands of Malta Malta and Gozo, as well as the city of Tripoli in modern Libya, were Order of Saint John of granted to the Order by Spanish Emperor Charles V in 1530, Jerusalem following the loss of Rhodes. The Ottoman Empire managed to Ordine di San Giovanni di capture Tripoli from the Order in 1551, but an attempt to take Gerusalemme (in Italian) Malta in 1565 failed. Ordni ta' San Ġwann ta' Following the 1565 siege, the Order decided to settle Ġerusalemm (in Maltese) permanently in Malta and began to construct a new capital city, 1530–1798 Valletta. For the next two centuries, Malta went through a Golden Age, characterized by a flourishing of the arts, architecture, and an overall improvement in Maltese society.[2] In the mid-17th century, the Order was the de jure proprietor over some islands in the Caribbean, making it the smallest state to colonize the Americas.. Flag The Order began to decline in the 1770s, and was severely Coat of arms weakened by the French Revolution in 1792. In 1798, French forces under Napoleon invaded Malta and expelled the Order, resulting in the French occupation of Malta. The Maltese eventually rebelled against the French, and the islands became a British protectorate in 1800. Malta was to be returned to the Order by the Treaty of Amiens in 1802, but the British remained in control and the islands formally became a British colony by the Treaty of Paris in 1814. -

Malta: the Locations Behing the Myths

ROUTES & STORYTELLING MALTA: THE LOCATIONS BEHING THE MYTHS FAMOUS: Film Festivals and Movie Tourism Across UNESCO Sites 18 months st st (1 May 2018 – 31 October 2019) Project: COS-TOURCCI-2017-03-03 TABLE OF CONTENTS *Note: numbers correspond to the sites that are marked in the maps below. A) MAPPING B) STORYTELLING DEVELOPMENT 1.2.3 Malta’s seaside, under the Plangent Rain Locations: Forti Sant' Anġlu, Auberge De France, Grand Harbour 4. In memoriam of Simshar Locations: The Malta Maritime Museum. References to the Church of Our Lady of Pompei - Madonna ta' Pompei and Marsaxlokk. 5.6. Valletta in the II World War: Malta’s story Locations: Valetta Waterfront, Lascaris War Rooms 7.8 Fort Saint Elmo: meeting point of international productions Locations: Fort Saint Elmo & Upper Barrakka gardens MAPPING GENERAL VIEW OF THE ROUTE: ADDITIONAL SHORT TRIP (SEE REFERENCES AT POINT 4) CORRELATION OF SITES AND FILMS/FILM EVENTS: STORYTELLING DEVELOPMENT Malta’s origins as mythical land, therefore, come from afar. With 7.000 years of culture and history, Malta is home to many myths and legends. The islands of Gozo and Malta have logged appearances in Homer’s Odyssey and The Bible, and Malta itself has even been proposed as the site of Atlantis. These stories have been a source of inspiration for artists for centuries. This attraction intensified during the period when Malta was under the British colonial rule, and the island, more than a bastion or citadel, became considered an exotic enclave in the middle of the Mediterranean, halfway between the East and the West. -

Tabuľka S Obsahom

Tabuľka s obsahom VALLETTA- MAP..................................................9 Valletta zošnurovaná história...................................1 MDINA - MAP.......................................................11 Miniatúry .................................................................1 BUS - ROUTES......................................................13 Maltézski rytieri .......................................................2 Malta z Wikipédie...................................................16 Katedrála sv. Jána ....................................................2 Geografia............................................................16 Veľmajstrov palác a knieža-sprievodca ...................2 Politika a politické zriadenie Malty...................16 Maltézsky kríž .........................................................3 Hospodárstvo.....................................................16 Maltézski rytieri .......................................................3 Dejiny.................................................................17 Valletta - Pamiatky a múzeá.....................................3 Historické pamiatky ..........................................17 10 miest, ktoré by ste mali navštíviť: Malta Obyvateľstvo......................................................17 Etnický pôvod....................................................17 1. Svätyne Hagar Qim a Mnajdra.............................4 Maltský jazyk.....................................................18 2. Megalitický chrám Ggantija............................4 -

The Maritime History and Archaeology of Malta

TRADE, PIRACY, AND NAVAL WARFARE IN THE CENTRAL MEDITERRANEAN: THE MARITIME HISTORY AND ARCHAEOLOGY OF MALTA A Dissertation by AYŞE DEVRİM ATAUZ Submitted to the Office of Graduate Studies of Texas A&M University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY May 2004 Major Subject: Anthropology TRADE, PIRACY, AND NAVAL WARFARE IN THE CENTRAL MEDITERRANEAN: THE MARITIME HISTORY AND ARCHAEOLOGY OF MALTA A Dissertation by AYŞE DEVRİM ATAUZ Submitted to Texas A&M University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY Approved as to style and content by: Kevin Crisman Cemal Pulak (Chair of Committee) (Member) James Bradford Luis Filipe Vieira de Castro (Member) (Member) David Carlson (Head of Department) May 2004 Major Subject: Anthropology iii ABSTRACT Trade, Piracy, and Naval Warfare in the Central Mediterranean: The Maritime History and Archaeology of Malta. (May 2004) Ayse Devrim Atauz, B.S., Middle East Technical University; M.A., Bilkent University Chair of Advisory Committee: Dr. Kevin Crisman Located approximately in the middle of the central Mediterranean channel, the Maltese Archipelago was touched by the historical events that effected the political, economic and cultural environment of Europe, North Africa, and the Middle East. The islands were close to the major maritime routes throughout history and they were often on the border between clashing military, political, religious, and cultural entities. For these reasons, the islands were presumed to have been strategically and economically important, and, thus, frequented by ships. An underwater archaeological survey around the archipelago revealed the scarcity of submerged cultural remains, especially pertaining to shipping and navigation. -

National Cultural Policy 2021 2 Acronyms and Abbreviations

NATIONAL CULTURAL POLICY 2021 2 ACRONYMS AND ABBREVIATIONS ACM Arts Council Malta BA Broadcasting Authority CCS Cultural and creative sectors EU European Union EUNIC European Union National Institutes for Culture GDP Gross Domestic Product HM Heritage Malta MCAST Malta College for Arts, Science and Technology MVPA Malta School for Visual and Performing Arts NCP National Cultural Policy NGO Non-governmental organisation NSO National Statistics Office PBS Public Broadcasting Services PCO Public Cultural Organisation SCH Superintendence of Cultural Heritage UCA Urban conservation area UN United Nations UNESCO United Nations Education, Scientific and Cultural Organisation UoM University of Malta WHS World Heritage Site NCP 2021 WORKING GROUP Chairperson Mr Mario Azzopardi (co-author) Members Mr Toni Attard (lead editor and co-author) Ms Esther Bajada Dr Noel Camilleri Ms Mary Anne Cauchi Mr Adrian Debattista (co-author) Dr Reuben Grima (co-author) Mr Albert Marshall Mr Caldon Mercieca (co-author) Dr Georgina Portelli (co-author) Dr Joanna Spiteri Dr Valerie Visanich (co-author) Translation by Simon Bartolo The working group acknowledges the contribution and participation of individuals and representatives of cultural organisations, Ministries and public entities in the public consultation process included as part of the drafting process of this document. 3 4 CONTENTS EXECUTIVE SUMMARY 9 INTRODUCTION THE RIGHT TO CULTURE 15 CULTURAL POLICY IMPLEMENTATION, EVALUATION AND MONITORING 19 Assessment and Development of the Institutional Capacities