The Wrath of Cochise: the Bascom Affair and the Origins of the Apache Wars Pdf

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Wrath of Cochise: the Bascom Affair and the Origins of the Apache Wars Free Ebook

FREETHE WRATH OF COCHISE: THE BASCOM AFFAIR AND THE ORIGINS OF THE APACHE WARS EBOOK Terry Mort | 352 pages | 17 Apr 2014 | Little, Brown Book Group | 9781472110923 | English | London, United Kingdom Review: 'The Wrath of Cochise: The Bascom Affair and the Origins of the Apache Wars,' by Terry Mort The Wrath of Cochise: The Bascom Affair and the Origins of the Apache Wars (English Edition) eBook: Mort, Terry, : Kindle Store. Bascom Affair Main article: Bascom Affair Open war with the Chiricahua Apaches had begun in , when Cochise, one of their chiefs, was accused by the Army of kidnapping an year-old Mexican boy, Felix Ward, stepson of Johnny Ward, later known as Mickey Free. The Bascom Massacre was a confrontation between Apache Indians and the United States Army under Lt. George Nicholas Bascom in the Arizona Territory in early It has been considered to have directly precipitated the decades-long Apache Wars between the United States and several tribes in the southwestern United States. Bascom affair Get this from a library! The wrath of Cochise: [the Bascom affair and the origins of the Apache wars]. [T A Mort] -- In February , the twelve- year-old son of Arizona rancher John Ward was kidnapped by Apaches. Ward followed their trail and reported the incident to patrols at Fort Buchanan, blaming a band of. The tale starts off in with Apaches attacking the John Ward ranch in the Sonoita Valley in Southern Arizona. Ward goes to Fort Buchanan to complain. The Army sends 2nd Lt. George Bascom and a patrol out to find the perpetrators. -

Arizona SAR Hosts First Grave Marking FALL 2018 Vol

FALL 2018 Vol. 113, No. 2 Q Orange County Bound for Congress 2019 Q Spain and the American Revolution Q Battle of Alamance Q James Tilton: 1st U.S. Army Surgeon General Arizona SAR Hosts First Grave Marking FALL 2018 Vol. 113, No. 2 24 Above, the Gen. David Humphreys Chapter of the Connecticut Society participated in the 67th annual Fourth of July Ceremony at Grove Street Cemetery in New Haven, 20 Connecticut; left, the Tilton Mansion, now the University and Whist Club. 8 2019 SAR Congress Convenes 13 Solid Light Reception 20 Delaware’s Dr. James Tilton in Costa Mesa, California The Prison Ship Martyrs Memorial Membership 22 Arizona’a First Grave Marking 14 9 State Society & Chapter News SAR Travels to Scotland 24 10 2018 SAR Annual Conference 16 on the American Revolution 38 In Our Memory/New Members 18 250th Series: The Battle 12 Tomb of the Unknown Soldier of Alamance 46 When You Are Traveling THE SAR MAGAZINE (ISSN 0161-0511) is published quarterly (February, May, August, November) and copyrighted by the National Society of the Sons of the American Revolution, 809 West Main Street, Louisville, KY 40202. Periodicals postage paid at Louisville, KY and additional mailing offices. Membership dues include The SAR Magazine. Subscription rate $10 for four consecutive issues. Single copies $3 with checks payable to “Treasurer General, NSSAR” mailed to the HQ in Louisville. Products and services advertised do not carry NSSAR endorsement. The National Society reserves the right to reject content of any copy. Send all news matter to Editor; send the following to NSSAR Headquarters: address changes, election of officers, new members, member deaths. -

Le Dossier Pédagogique

La flèche brisée / Collège au cinéma 53 / Yannick Lemarié – 2010-2011 1 Dossier pédagogique 6e / 5e Collège au cinéma 53 Par Yannick Lemarié / Action culturelle – Rectorat de Nantes La flèche brisée / Collège au cinéma 53 / Yannick Lemarié – 2010-2011 2 Sommaire Analyse de l’affiche………………………………………………….. p.3-4 Avant la projection : un genre, le western………………………... p.5-6 Après la projection : 1-Les héros…………………………………………………………... p.7-8 2-La quête…………………………………………………………… p.9-10 3-Deux mondes…………………………………………………….... p.11-12 4-Le miroir…………………………………………………………… p.13-14 5-Les passages………………………………………………………. p.15-17 6-La communication…………………………………………………. p.18-19 7-De l’histoire au mythe……………………………………………. p.20-22 8-La loi………………………………………………………………. p.23-24 9-Annexes-Documents pour le cours……………………………… p.25-30 Pour toutes remarques, demandes et précisions : [email protected] La flèche brisée / Collège au cinéma 53 / Yannick Lemarié – 2010-2011 3 Analyse de l’affiche Dynamique de l’affiche L’affiche manifeste une belle dynamique, de sorte que le film apparaît d’emblée comme un film d’action. Tout est fait pour traduire le mouvement : le combat au premier plan (deux ennemis luttent pour leur survie) / les chevaux au galop / la pente du terrain / le titre lui- même. Ce mouvement est tout entier dirigé vers James Stewart : il est le héros. Plusieurs éléments de l’affiche le confirment : 9 Seul son nom apparaît en haut de l’affiche. 9 Le jeune indien tente de lui porter un coup ; les chevaux se dirigent vers lui ; la jeune indienne le regarde. Il est le point d’aboutissement de toutes les lignes de force ; le point de convergence de tous les regards. -

The Chiricahua Apache from 1886-1914, 35 Am

American Indian Law Review Volume 35 | Number 1 1-1-2010 Values in Transition: The hirC icahua Apache from 1886-1914 John W. Ragsdale Jr. Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.law.ou.edu/ailr Part of the Indian and Aboriginal Law Commons, Indigenous Studies Commons, Other History Commons, Other Languages, Societies, and Cultures Commons, and the United States History Commons Recommended Citation John W. Ragsdale Jr., Values in Transition: The Chiricahua Apache from 1886-1914, 35 Am. Indian L. Rev. (2010), https://digitalcommons.law.ou.edu/ailr/vol35/iss1/9 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by University of Oklahoma College of Law Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in American Indian Law Review by an authorized editor of University of Oklahoma College of Law Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. VALUES IN TRANSITION: THE CHIRICAHUA APACHE FROM 1886-1914 John W Ragsdale, Jr.* Abstract Law confirms but seldom determines the course of a society. Values and beliefs, instead, are the true polestars, incrementally implemented by the laws, customs, and policies. The Chiricahua Apache, a tribal society of hunters, gatherers, and raiders in the mountains and deserts of the Southwest, were squeezed between the growing populations and economies of the United States and Mexico. Raiding brought response, reprisal, and ultimately confinement at the loathsome San Carlos Reservation. Though most Chiricahua submitted to the beginnings of assimilation, a number of the hardiest and least malleable did not. Periodic breakouts, wild raids through New Mexico and Arizona, and a labyrinthian, nearly impenetrable sanctuary in the Sierra Madre led the United States to an extraordinary and unprincipled overreaction. -

A Pledge of Peace: Evidence of the Cochise-Howard Treaty Campsite

154 Deni J. Seymour of the treaty conference has evaded identification George Robertson for several reasons. Historical events, like these treaty talks, took place in remote areas without benefit of precise coordinates. Without some A Pledge of Peace: Evidence kind of physical evidence, there is generally of the Cochise-Howard Treaty no way to ascertain the exact location. The subtlety of the material culture relating to this Campsite prominent Native American group has precluded identification of the treaty-conference location ABSTRACT based upon archaeological evidence until now, particularly without corroboration from other Historical maps, documents, and photographs have been sources. Moreover, it is generally beyond the combined with archaeological data to confirm the location capacity of the archaeological discipline to of the Cochise-Howard treaty camp. Brigadier General Oliver isolate evidence that is uniquely and inimitably Otis Howard, his escorts Lieutenant Joseph Alton Sladen indicative of such a specific event. and Thomas Jonathan Jeffords, and the Chiricahua Apache Through a series of means, the Cochise- chief Cochise met in the foothills of the Dragoon Moun- tains of southern Arizona in October 1872 to negotiate the Howard treaty site has been now identified. surrender and relocation of this “most troublesome Apache Various types of evidence have been used to group” (Bailey 1999:17). Warfare between the Apache and finally confirm the accurate location of the the Americans had been ongoing for more than a decade. treaty camp. These include the combined use This meeting culminated in a peace treaty between Cochise’s Chokonen band and the United States government. Photographs of unique boulder formations confirm the treaty-negotiation location, and written landscape descriptions provide further verification. -

Foundation Document Overview, Fort Bowie National Historic Site, Arizona

NATIONAL PARK SERVICE • U.S. DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR. Foundation Document Overview. Fort Bowie National Historic Site. Arizona. Contact Information. For more information about the Fort Bowie National Historic Site Foundation Document, contact: [email protected] or (520) 847-2500 or write to: Superintendent, Fort Bowie National Historic Site, 3327 Old Fort Bowie Road, Bowie, AZ 85605 Purpose. Significance. Significance statements express why Fort Bowie National Historic Site resources and values are important enough to merit national park unit designation. Statements of significance describe why an area is important within a global, national, regional, and systemwide context. These statements are linked to the purpose of the park unit, and are supported by data, research, and consensus. Significance statements describe the distinctive nature of the park and inform management decisions, focusing efforts on preserving and protecting the most important resources and values of the park unit. • For over 25 years Fort Bowie was central to late 19th-century US military campaign against the Chiricahua Apaches. The final surrender by Geronimo in 1886 to troops stationed at Fort Bowie brought an end to two centuries of Apache warfare with the Spanish, Mexicans, and Americans in southeast Arizona. • Designated a national historic landmark in 1960, Fort Bowie National Historic Site preserves the remnants of the fort structures that are key to understanding the history FORT BOWIE NATIONAL HISTORIC of Apache Pass and the US military presence there, which SITE preserves and interprets the ultimately opened the region to unrestricted settlement. history, landscape, and remaining • Apache Pass offers the most direct, accessible route between structures of Fort Bowie, a US Army the Chiricahua and Dos Cabezas ranges, with a reliable outpost which guarded the strategic water supply available from Apache Spring. -

School District Reference Map (2010 Census

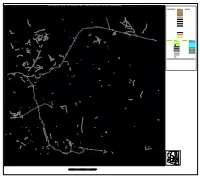

32.536076N 110.489265W SCHOOL DISTRICT REFERENCE MAP (2010 CENSUS): Cochise County, AZ UNI 32.508364N 04570 108.97127W PIMA 019 LEGEND GREENLEE 011 GREENLEE 011 GRAHAM 009 GRAHAM SYMBOL DESCRIPTION SYMBOL LABEL STYLE PIMA 019 G R ELM A Federal American Indian UNI UNI UNI H UNI ELM A Reservation L'ANSE RES 1880 01260 06440 08410 07240 M 02600 07860 0 0 9 Off-Reservation Trust Land T1880 State American Indian Reservation Tama Res 4125 EENLEE 011 GRAHAM 009 GR Alaska Native Regional N Sand Storm Ln COCHISE 003 COCHISE 003 Corporation NANA ANRC 52120 Dee Rd Union Pacific RR 59 d 6 W Reagan Rd d e R v d R State (or statistically R n F A S a o l F r a a r equivalent entity) Ranch House Rd u t NEW YORK 36 g n a e d d S C R W Ranch House Rd anch R h Rd W R Tail Ranc Red 191 County (or statistically Fort E Williams Rd N osewood Rd Grove P R Grant Rd a g C d e equivalent entity) ERIE 029 N Layton Ln Ln Layton N R a R h a Trl s c n ue a Oak n c h b a h rl a N R n e T Ranch Rd N Rd o s o o d l r H D R r R R n O u M e W a O Minor Civil Division t b d o o d s n o i r n i b R c k R o F uzen R S a h W L a d 1,2 K s R r l (MCD) d R N a R Gamez R z R d d d e d o N Bristol town 07485 k S 6 c h 9 i c 1 Ingram Rd N an Fan Rd mez Rd R Ga N d W Ave Central Black Luzena Rd Rd R R d Hardy Rd d N Consolidated City a nion Pacific RR ip R U r z P t o o irs S r i a n A MILFORD 47500 E Sag u t N Boggs Rd W Saguaro Rd W Saguaro Rd o W Boggs W W Luzena W Rockho a d Rd Rd W Ellis Ranch Rd use Rd y R Saddle Dr 1,3 e d k N Bowie 07380 Incorporated Place v R a A ELM A h -

Archeological Findings of the Battle of Apache Pass, Fort Bowie National Historic Site Non-Sensitive Version

National Park Service U.S. Department of the Interior Resource Stewardship and Science Archeological Findings of the Battle of Apache Pass, Fort Bowie National Historic Site Non-Sensitive Version Natural Resource Report NPS/FOBO/NRR—2016/1361 ON THIS PAGE Photograph (looking southeast) of Section K, Southeast First Fort Hill, where many cannonball fragments were recorded. Photograph courtesy National Park Service. ON THE COVER Top photograph, taken by William Bell, shows Apache Pass and the battle site in 1867 (courtesy of William A. Bell Photographs Collection, #10027488, History Colorado). Center photograph shows the breastworks as digitized from close range photogrammatic orthophoto (courtesy NPS SOAR Office). Lower photograph shows intact cannonball found in Section A. Photograph courtesy National Park Service. Archeological Findings of the Battle of Apache Pass, Fort Bowie National Historic Site Non-sensitive Version Natural Resource Report NPS/FOBO/NRR—2016/1361 Larry Ludwig National Park Service Fort Bowie National Historic Site 3327 Old Fort Bowie Road Bowie, AZ 85605 December 2016 U.S. Department of the Interior National Park Service Natural Resource Stewardship and Science Fort Collins, Colorado The National Park Service, Natural Resource Stewardship and Science office in Fort Collins, Colorado, publishes a range of reports that address natural resource topics. These reports are of interest and applicability to a broad audience in the National Park Service and others in natural resource management, including scientists, conservation and environmental constituencies, and the public. The Natural Resource Report Series is used to disseminate comprehensive information and analysis about natural resources and related topics concerning lands managed by the National Park Service. -

Lieutenant Faison's Account of the Geronimo Campaign

Lieutenant Faison’s Account of the Geronimo Campaign By Edward K. Faison Introduction The Sky Islands region of southeastern Arizona and northeastern Sonora consists of 40 wooded mountain ranges scattered in a sea of desert scrub and arid grassland. To the west is the Sonoran Desert. To the east is the Chihuahuan Desert. To the north are the Arizona–New Mexico Mountains, and to the south is the Sierra Madre Occidental Range where elevations rise almost 10,000 feet from canyon floor to forested ridge. This “roughest portion of the continent,” in the words of General George Crook, was the setting of the Apache Wars—an American Indian–US Army conflict (1861–1886) unparalleled in its ferocity, physical demands, and unorthodox tactics. For a young lieutenant raised on North Carolina’s coastal plain and schooled in traditional warfare, Arizona in the 1880s was no ordinary place to embark on a military career.1 From this formative experience came this memoir by Lieutenant Samson L. Faison, which chronicles his eleven months of service in the Southwest during the Geronimo Campaign of 1885–1886. He wrote it in 1898 while serving at West Point as senior instructor of infantry tactics. It was never published.2 Faison’s account begins two days after the May 17, 1885 breakout of Geronimo, Natchez, Nana, and 140 Chiricahua Apache followers from the San Carlos Reservation in Arizona. Along the way, we revisit important milestones such as the death of Captain Emmet Crawford at the hands of Mexican militia, the surrender Faison's 1883 West Point Graduaon Photo conference between Geronimo and General Crook at Cañon de (USMA photo) los Embudos, and Geronimo’s subsequent flight back to Mexico followed by Crook’s resignation. -

Cochise Quarterly

THE COCHISE QUARTERLY Volume 1 Number 2 June, 1971 CONTENTS Early Hunters and Gatherers in Southeastern Arizona by Ric Windmiller 3 From Rocks to Gadgets A History of Cochise County, Arizona by Carl Trischka 16 A Cochise Culture Human Skeleton From Southeastern Arizona by Kenneth R. McWilliams 24 Cover designed by Ray Levra, Cochise College A Publication of the Cochise County Historical and Archaeological Society P. O. Box 207 Pearce, Arizona 85625 2 ARIZONA DOCUMENTS It will be one of the purposes of The Cochise Qnarterly to pub lish from time to time rare and often unpublished documents per taining to Arizona history and particularly to Cochise County. The first to appear in this series is the executive order establishing the Chiricahua Indian Reservation and the San Carlos division of the White Mountain Reservation. It is of particular interest to Arizonians for the exact boundaries established. In the fall of 1872, Major General O. O. Howard, emissary of President U. S. Grant, made peace with the Chiricahua Apaches and Chief Cochise in their Stronghold in the Dragoon Mountains. During the course of the negotiations, the Indians agreed to go onto a reser· vation with Tom Jeffords as their agent. Upon his return to the nation's capital, General Howard made his report to the President and insisted that the reservation be estab lished as soon as possible. President Grant did not delay. On Decem ber 14, 1872 he issued an executive order in accordance with the agreement Howard had made with Cochise. That executive order follows: EXECUTIVE MANSION, December 14, 1872. -

American Indian Biographies Index

American Indian Biographies Index A ABC: Americans Before Columbus, 530 Ace Daklugie, 245 Actors; Banks, Dennis, 21-22; Beach, Adam, 24; Bedard, Irene, 27-28; Cody, Iron Eyes, 106; George, Dan, 179; Greene, Graham, 194-195; Means, Russell, 308-310; Rogers, Will, 425-430; Sampson, Will, 443; Silverheels, Jay, 461; Studi, Wes, 478 Adair, John L., 1 Adams, Abigail, 289 Adams, Hank, 530 Adams, Henry, 382 Adams, John Quincy, 411 Adario, 1-2 Adate, 149 Adobe Walls, Battles of, 231, 365, 480 Agona, 150 AIF. See American Indian Freedom Act AIM. See American Indian Movement AIO. See Americans for Indian Opportunity AISES. See American Indian Science and Engineering Society Alaska Native Brotherhood, 374 Alaska Native Sisterhood, 374 Alaskan Anti-Discrimination Act, 374 Alcatraz Island occupation; and Bellecourt, Clyde, 29; and Mankiller, Wilma, 297; and Oakes, Richard, 342; and Trudell, John, 508 Alexie, Sherman, 2-5 Alford, Thomas Wildcat, 5 Allen, Alvaren, 466 Allen, Paula Gunn, 6-9 Alligator, 9-10, 246 Allotment, 202, 226 Amadas, Philip, 371 American Horse, 10-12, 26 American Indian Chicago Conference, 530 American Indian Freedom Act, 30 American Indian Historical Society, 116 American Indian Movement, 21, 129, 369; and Bellecourt, Clyde H., 29; and Bellecourt, Vernon, 32; creation of, 530; and Crow Dog, Leonard, 128; and Fools Crow, Frank, 169; and Means, Russell, 308; and Medicine, Bea, 311; and Oakes, Richard, 342-343; and Pictou Aquash, Anna Mae, 376 American Indian Science and Engineering Society, 391 American Revolution, 66; and Cayuga, 281; and Cherokee, 61, 346; and Creek, 288; and Delaware, 544; and Iroquois, 63, 66-67, 69, 112-113; and Lenni Lenape, 224; and Mahican, 341; and Miami, 277; and Mohawk, 68; and Mohegan, 345; and Ottawa, 387; and Senecas, 52; and Shawnee, 56, 85, 115, 497 Americans for Indian Opportunity, 207 ANB. -

Feasibility Study for the SANTA CRUZ VALLEY NATIONAL HERITAGE AREA

Feasibility Study for the SANTA CRUZ VALLEY NATIONAL HERITAGE AREA FINAL Prepared by the Center for Desert Archaeology April 2005 CREDITS Assembled and edited by: Jonathan Mabry, Center for Desert Archaeology Contributions by (in alphabetical order): Linnea Caproni, Preservation Studies Program, University of Arizona William Doelle, Center for Desert Archaeology Anne Goldberg, Department of Anthropology, University of Arizona Andrew Gorski, Preservation Studies Program, University of Arizona Kendall Kroesen, Tucson Audubon Society Larry Marshall, Environmental Education Exchange Linda Mayro, Pima County Cultural Resources Office Bill Robinson, Center for Desert Archaeology Carl Russell, CBV Group J. Homer Thiel, Desert Archaeology, Inc. Photographs contributed by: Adriel Heisey Bob Sharp Gordon Simmons Tucson Citizen Newspaper Tumacácori National Historical Park Maps created by: Catherine Gilman, Desert Archaeology, Inc. Brett Hill, Center for Desert Archaeology James Holmlund, Western Mapping Company Resource information provided by: Arizona Game and Fish Department Center for Desert Archaeology Metropolitan Tucson Convention and Visitors Bureau Pima County Staff Pimería Alta Historical Society Preservation Studies Program, University of Arizona Sky Island Alliance Sonoran Desert Network The Arizona Nature Conservancy Tucson Audubon Society Water Resources Research Center, University of Arizona PREFACE The proposed Santa Cruz Valley National Heritage Area is a big land filled with small details. One’s first impression may be of size and distance—broad valleys rimmed by mountain ranges, with a huge sky arching over all. However, a closer look reveals that, beneath the broad brush strokes, this is a land of astonishing variety. For example, it is comprised of several kinds of desert, year-round flowing streams, and sky island mountain ranges.