Cochise Quarterly

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Le Dossier Pédagogique

La flèche brisée / Collège au cinéma 53 / Yannick Lemarié – 2010-2011 1 Dossier pédagogique 6e / 5e Collège au cinéma 53 Par Yannick Lemarié / Action culturelle – Rectorat de Nantes La flèche brisée / Collège au cinéma 53 / Yannick Lemarié – 2010-2011 2 Sommaire Analyse de l’affiche………………………………………………….. p.3-4 Avant la projection : un genre, le western………………………... p.5-6 Après la projection : 1-Les héros…………………………………………………………... p.7-8 2-La quête…………………………………………………………… p.9-10 3-Deux mondes…………………………………………………….... p.11-12 4-Le miroir…………………………………………………………… p.13-14 5-Les passages………………………………………………………. p.15-17 6-La communication…………………………………………………. p.18-19 7-De l’histoire au mythe……………………………………………. p.20-22 8-La loi………………………………………………………………. p.23-24 9-Annexes-Documents pour le cours……………………………… p.25-30 Pour toutes remarques, demandes et précisions : [email protected] La flèche brisée / Collège au cinéma 53 / Yannick Lemarié – 2010-2011 3 Analyse de l’affiche Dynamique de l’affiche L’affiche manifeste une belle dynamique, de sorte que le film apparaît d’emblée comme un film d’action. Tout est fait pour traduire le mouvement : le combat au premier plan (deux ennemis luttent pour leur survie) / les chevaux au galop / la pente du terrain / le titre lui- même. Ce mouvement est tout entier dirigé vers James Stewart : il est le héros. Plusieurs éléments de l’affiche le confirment : 9 Seul son nom apparaît en haut de l’affiche. 9 Le jeune indien tente de lui porter un coup ; les chevaux se dirigent vers lui ; la jeune indienne le regarde. Il est le point d’aboutissement de toutes les lignes de force ; le point de convergence de tous les regards. -

The Chiricahua Apache from 1886-1914, 35 Am

American Indian Law Review Volume 35 | Number 1 1-1-2010 Values in Transition: The hirC icahua Apache from 1886-1914 John W. Ragsdale Jr. Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.law.ou.edu/ailr Part of the Indian and Aboriginal Law Commons, Indigenous Studies Commons, Other History Commons, Other Languages, Societies, and Cultures Commons, and the United States History Commons Recommended Citation John W. Ragsdale Jr., Values in Transition: The Chiricahua Apache from 1886-1914, 35 Am. Indian L. Rev. (2010), https://digitalcommons.law.ou.edu/ailr/vol35/iss1/9 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by University of Oklahoma College of Law Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in American Indian Law Review by an authorized editor of University of Oklahoma College of Law Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. VALUES IN TRANSITION: THE CHIRICAHUA APACHE FROM 1886-1914 John W Ragsdale, Jr.* Abstract Law confirms but seldom determines the course of a society. Values and beliefs, instead, are the true polestars, incrementally implemented by the laws, customs, and policies. The Chiricahua Apache, a tribal society of hunters, gatherers, and raiders in the mountains and deserts of the Southwest, were squeezed between the growing populations and economies of the United States and Mexico. Raiding brought response, reprisal, and ultimately confinement at the loathsome San Carlos Reservation. Though most Chiricahua submitted to the beginnings of assimilation, a number of the hardiest and least malleable did not. Periodic breakouts, wild raids through New Mexico and Arizona, and a labyrinthian, nearly impenetrable sanctuary in the Sierra Madre led the United States to an extraordinary and unprincipled overreaction. -

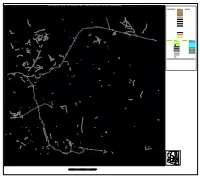

A Pledge of Peace: Evidence of the Cochise-Howard Treaty Campsite

154 Deni J. Seymour of the treaty conference has evaded identification George Robertson for several reasons. Historical events, like these treaty talks, took place in remote areas without benefit of precise coordinates. Without some A Pledge of Peace: Evidence kind of physical evidence, there is generally of the Cochise-Howard Treaty no way to ascertain the exact location. The subtlety of the material culture relating to this Campsite prominent Native American group has precluded identification of the treaty-conference location ABSTRACT based upon archaeological evidence until now, particularly without corroboration from other Historical maps, documents, and photographs have been sources. Moreover, it is generally beyond the combined with archaeological data to confirm the location capacity of the archaeological discipline to of the Cochise-Howard treaty camp. Brigadier General Oliver isolate evidence that is uniquely and inimitably Otis Howard, his escorts Lieutenant Joseph Alton Sladen indicative of such a specific event. and Thomas Jonathan Jeffords, and the Chiricahua Apache Through a series of means, the Cochise- chief Cochise met in the foothills of the Dragoon Moun- tains of southern Arizona in October 1872 to negotiate the Howard treaty site has been now identified. surrender and relocation of this “most troublesome Apache Various types of evidence have been used to group” (Bailey 1999:17). Warfare between the Apache and finally confirm the accurate location of the the Americans had been ongoing for more than a decade. treaty camp. These include the combined use This meeting culminated in a peace treaty between Cochise’s Chokonen band and the United States government. Photographs of unique boulder formations confirm the treaty-negotiation location, and written landscape descriptions provide further verification. -

School District Reference Map (2010 Census

32.536076N 110.489265W SCHOOL DISTRICT REFERENCE MAP (2010 CENSUS): Cochise County, AZ UNI 32.508364N 04570 108.97127W PIMA 019 LEGEND GREENLEE 011 GREENLEE 011 GRAHAM 009 GRAHAM SYMBOL DESCRIPTION SYMBOL LABEL STYLE PIMA 019 G R ELM A Federal American Indian UNI UNI UNI H UNI ELM A Reservation L'ANSE RES 1880 01260 06440 08410 07240 M 02600 07860 0 0 9 Off-Reservation Trust Land T1880 State American Indian Reservation Tama Res 4125 EENLEE 011 GRAHAM 009 GR Alaska Native Regional N Sand Storm Ln COCHISE 003 COCHISE 003 Corporation NANA ANRC 52120 Dee Rd Union Pacific RR 59 d 6 W Reagan Rd d e R v d R State (or statistically R n F A S a o l F r a a r equivalent entity) Ranch House Rd u t NEW YORK 36 g n a e d d S C R W Ranch House Rd anch R h Rd W R Tail Ranc Red 191 County (or statistically Fort E Williams Rd N osewood Rd Grove P R Grant Rd a g C d e equivalent entity) ERIE 029 N Layton Ln Ln Layton N R a R h a Trl s c n ue a Oak n c h b a h rl a N R n e T Ranch Rd N Rd o s o o d l r H D R r R R n O u M e W a O Minor Civil Division t b d o o d s n o i r n i b R c k R o F uzen R S a h W L a d 1,2 K s R r l (MCD) d R N a R Gamez R z R d d d e d o N Bristol town 07485 k S 6 c h 9 i c 1 Ingram Rd N an Fan Rd mez Rd R Ga N d W Ave Central Black Luzena Rd Rd R R d Hardy Rd d N Consolidated City a nion Pacific RR ip R U r z P t o o irs S r i a n A MILFORD 47500 E Sag u t N Boggs Rd W Saguaro Rd W Saguaro Rd o W Boggs W W Luzena W Rockho a d Rd Rd W Ellis Ranch Rd use Rd y R Saddle Dr 1,3 e d k N Bowie 07380 Incorporated Place v R a A ELM A h -

Ezrasarchives2015 Article2.Pdf (514.9Kb)

Ezra’s Archives | 27 From Warfare to World Fair: The Ideological Commodification of Geronimo in the Late Nineteenth and Early Twentieth-Century United States Kai Parmenter A Brief History: Geronimo and the Chiricahua Apaches Of all the Native American groups caught in the physical and ideological appropriations of expansionist-minded Anglo-Americans in the nineteenth and twentieth centuries, the Apache are often framed by historiographical and visual sources as distinct from their neighboring bands and tribes.1 Unlike their Arizona contemporaries the Navajo and the Hopi, who were ultimately relegated to mythical status as domesticated savage and artistic curiosity, the Apache have been primarily defined by their resistance to Anglo-American subjugation in what came to be known as the Apache Wars. This conflict between the Apache bands of southeastern Arizona and northern Mexico—notably the Chiricahua, the primary focus of this study—and the United States Army is loosely defined as the period between the conclusion of the Mexican-American War in 1848 and the final surrender of Geronimo and Naiche to General Nelson A. Miles in September 1886. Historian Frederick W. Turner, who published a revised and annotated edition of Geronimo’s 1906 oral autobiography, 1 The terms “Anglo-American,” “Euro-American” and “white American” are used interchangeably throughout the piece as a means of avoiding the monotony of repetitious diction. The same may be applied to Geronimo, herein occasionally referred to as “infamous Chiricahua,” “Bedonkohe leader,” etc. 28 | The Ideological Commodification of Geronimo in the Late Nineteenth and Early Twentieth-Century United States notes that early contact between the Chiricahua and white Americans was at that point friendly, “probably because neither represented a threat to the other.”2 Yet the United States’ sizable land acquisitions following the Mexican-American War, coupled with President James K. -

General Crook's Administration in Arizona, 1871-75

General Crook's administration in Arizona, 1871-75 Item Type text; Thesis-Reproduction (electronic) Authors Bahm, Linda Weldy Publisher The University of Arizona. Rights Copyright © is held by the author. Digital access to this material is made possible by the University Libraries, University of Arizona. Further transmission, reproduction or presentation (such as public display or performance) of protected items is prohibited except with permission of the author. Download date 29/09/2021 11:58:29 Link to Item http://hdl.handle.net/10150/551868 GENERAL CROOK'S ADMINISTRATION IN ARIZONA, 1871-75 by Linda Weldy Bahm A Thesis Submitted to the Faculty of the DEPARTMENT OF HISTORY In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements For the Degree of MASTER OF ARTS In the Graduate College THE UNIVERSITY OF ARIZONA 19 6 6 STATEMENT BY AUTHOR This thesis has been submitted in partial fu lfill ment of requirements for an advanced degree at The University of Arizona and is deposited in the University Library to be made available to borrowers under rules of the Library. Brief quotations from this thesis are allowable without special permission, provided that accurate acknowledgment of source is made. Requests for per mission for extended quotation from or reproduction of this manuscript in whole or in part may be granted by the head of the major department or the Dean of the Graduate College when in his judgment the proposed use of the material is in the interests of scholarship. In all other instances, however, permission must be obtained from the author. SIGNED: APPROVAL BY THESIS DIRECTOR This thesis has been approved on the date shown below: J/{ <— /9 ^0 JOHN ALEXANDER CARROLL ^ T 5 ite Professor of History PREFACE In the four years following the bloody attack on an Indian encampment by a Tucson posse early in 1871, the veteran professional soldier George Crook had primary responsibility for the reduction and containment of the "hostile" Indians of the Territory of Arizona. -

Angela M. Ross

The Princess Production: Locating Pocahontas in Time and Place Item Type text; Electronic Dissertation Authors Ross, Angela Publisher The University of Arizona. Rights Copyright © is held by the author. Digital access to this material is made possible by the University Libraries, University of Arizona. Further transmission, reproduction or presentation (such as public display or performance) of protected items is prohibited except with permission of the author. Download date 02/10/2021 20:51:52 Link to Item http://hdl.handle.net/10150/194511 THE PRINCESS PRODUCTION: LOCATING POCAHONTAS IN TIME AND PLACE by Angela M. Ross ________________________ A Dissertation Submitted to the Faculty of the DEPARTMENT OF COMPARATIVE CULTURAL AND LITERARY STUDIES In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements For the Degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY In the Graduate College THE UNIVERSITY OF ARIZONA 2008 2 THE UNIVERSITY OF ARIZONA GRADUATE COLLEGE As members of the Dissertation Committee, we certify that we have read the dissertation prepared by Angela Ross entitled The Princess Production: Locating Pocahontas in Time and Place and recommend that it be accepted as fulfilling the dissertation requirement for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy. _______________________________________________________________________ Date: 11/03/2008 Susan White _______________________________________________________________________ Date: 11/03/2008 Laura Briggs _______________________________________________________________________ Date: 11/03/2008 Franci Washburn Final approval -

Apaches and Comanches on Screen Kenneth Estes Hall East Tennessee State University, [email protected]

East Tennessee State University Digital Commons @ East Tennessee State University ETSU Faculty Works Faculty Works 1-1-2012 Apaches and Comanches on Screen Kenneth Estes Hall East Tennessee State University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://dc.etsu.edu/etsu-works Part of the American Film Studies Commons, and the Film and Media Studies Commons Citation Information Hall, Kenneth Estes. (true). 2012. Apaches and Comanches on Screen. Studies in the Western. Vol.20 27-41. http://www.westernforschungszentrum.de/ This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Faculty Works at Digital Commons @ East Tennessee State University. It has been accepted for inclusion in ETSU Faculty Works by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons @ East Tennessee State University. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Apaches and Comanches on Screen Copyright Statement This document was published with permission from the journal. It was originally published in the Studies in the Western. This article is available at Digital Commons @ East Tennessee State University: https://dc.etsu.edu/etsu-works/591 Apaches and Comanches on Screen Kenneth E. Hall A generally accurate appraisal of Western films might claim that In dians as hostiles are grouped into one undifferentiated mass. Popular hostile groups include the Sioux (without much differentiation between tribes or bands, the Apaches, and the Comanches). Today we will examine the images of Apache and Comanche groups as presen ted in several Western films. In some cases, these groups are shown with specific, historically identifiable leaders such as Cochise, Geron imo, or Quanah Parker. -

De Alcalá COMISIÓN DE ESTUDIOS OFICIALES DE POSGRADO Y DOCTORADO

� Universidad /::.. f .. :::::. de Alcalá COMISIÓN DE ESTUDIOS OFICIALES DE POSGRADO Y DOCTORADO ACTA DE EVALUACIÓN DE LA TESIS DOCTORAL Año académico 201Ci/W DOCTORANDO: SERRANO MOYA, MARIA ELENA D.N.1./PASAPORTE: ****0558D PROGRAMA DE DOCTORADO: D402 ESTUDIOS NORTEAMERICANOS DPTO. COORDINADOR DEL PROGRAMA: INSTITUTO FRANKLIN TITULACIÓN DE DOCTOR EN: DOCTOR/A POR LA UNIVERSIDAD DE ALCALÁ En el día de hoy 12/09/19, reunido el tribunal de evaluación nombrado por la Comisión de Estudios Oficiales de Posgrado y Doctorado de la Universidad y constituido por los miembros que suscriben la presente Acta, el aspirante defendió su Tesis Doctoral, elaborada bajo la dirección de JULIO CAÑERO SERRANO// DAVID RÍO RAIGADAS. Sobre el siguiente tema: VIEWS OF NATIVEAMERICANS IN CONTEMPORARY U.S. AMERICAN CINEMA Finalizada la defensa y discusión de la tesis, el tribunal acordó otorgar la CALIFICACIÓN GLOBAL 1 de (no apto, ) aprobado, notable y sobresaliente : _=-s·--'o---'g""'--/\.-E._5_---'-/l i..,-/ _&_v_J_�..::;_________ ______ Alca la, de Henares, .............,t-z. de ........J&Pr.........../015"{(,.......... de ..........2'Dl7.. .J ,,:: EL SECRETARIO u EL PRESIDENTE .J ,,:: UJ Q Q ,,:: Q V) " Fdo.: AITOR UJ Fdo.: FRANCISCO MANUEL SÁEZ DE ADANA HERRERO Fdo.:MARGARITA ESTÉVEZ SAÁ > IBARROLLA ARMENDARIZ z ;::, Con fe0hag.E_de__ ��{� e__ � j:l1a Comisión Delegada de la Comisión de Estudios Oficiales de Posgrado, a la vista de los votos emitidos de manera anónima por el tribunal que ha juzgado la tesis, resuelve: FIRMA DEL ALUMNO, O Conceder la Mención de "Cum Laude" � No conceder la Mención de "Cum Laude" La Secretariade la Comisión Delegada Fdo.: SERRANO MOYA, MARIA ELENA 1 La calificación podrá ser "no apto" "aprobado" "notable" y "sobresaliente". -

After Making Peace in 1872 Cochise Retired to the New Chiricahua Reservation, Where He Died of Natural Causes in 1874

After making peace in 1872 Cochise retired to the new Chiricahua Reservation, where he died of natural causes in 1874. He was buried somewhere in his favorite camp in Arizona's Dragoon Mountains, now called Cochise Stronghold. Only his people & Tom Jeffords, his only white friend, knew the exact location of his resting place, & they took the secret to their graves. Chiricahua Wickups as recorded by anthropologist Morris Opler: "The home in which the family lives is made by the men and is ordinarily a circular, dome-shaped brush dwelling, with the floor at ground level. It is eight feet high at the center and approximately seven feet in diameter. To build it, long fresh poles of oak or willow are driven into the ground or placed in holes made with a digging stick. These poles, which form the framework, are arranged at one-foot intervals and are bound together at the top with yucca -leaf strands. Over them a thatching of bundles of big bluestem grass or bear grass is tied, shingle style, with yucca strings. A smoke hole opens above a central fireplace. A hide, suspended at the entrance, is fixed on a cross-beam so that it may be swung forward or backward. The doorway may face in any direction. For waterproofing, pieces of hide are thrown over the outer hatching, and in rainy weather, if a fire is not needed, even the smoke hole is covered. In warm, dry weather much of the outer roofing is stripped off. It takes approximately three days to erect a sturdy dwelling of this type. -

La Flèche Brisée (Broken Arrow) De Delmer Daves (USA, 1950, 1H33)

La flèche brisée (Broken Arrow) de Delmer Daves (USA, 1950, 1h33) Présentation : Résumé : La guerre fait rage entre les blancs et les Apaches. Ancien chercheur d’or, devenu éclaireur, Tom Jeffords apprend patiemment la langue indienne, puis part dans les montagnes rencontrer le chef Cochise pour faire des propositions de paix. Hôte du camp Apache, il s’éprend d’une indienne d’une merveilleuse beauté, Sonseeahray. De retour à Tucson, Tom annonce les premières promesses de Cochise à la population incrédule : les courriers seront autorisés à traverser son territoire. En brisant symboliquement une flèche, Cochise scelle avec le vieux général le début de la paix avec les Blancs tandis que Tom épouse Sonseeahray à la mode indienne. Mais Geronimo et quelques-uns de ses partisans décident de continuer le combat ainsi que quelques Blancs… Histoire détaillée : (selon les chapitres du DVD) Dans le générique du début, on voit des dessins colorés qui représentent des motifs indiens que l’on retrouvera lors des danses de cérémonie. Chapitre 1 : Rencontre inattendue Arizona 1870. Les luttes avec les indiens durent sur le territoire depuis plus de dix ans : les Apaches mènent un guerre sans merci aux Blancs venus les décimer pour prendre leurs terres. Chercheur d’or, ex-soldat de l’Union, Tom Jeffords trouve un jeune Apache Chiricahua blessé, au-dessus duquel tournoient des buses. Il lui donne à boire, retire les plombs qu’il a reçus et le sauve de la mort. Il s’attire la reconnaissance de sa tribu et celle de Cochise, lequel a, pour la première fois, réussi à regrouper sous sa bannière l’ensemble des tribus apaches. -

The Wrath of Cochise: the Bascom Affair and the Origins of the Apache Wars Pdf

FREE THE WRATH OF COCHISE: THE BASCOM AFFAIR AND THE ORIGINS OF THE APACHE WARS PDF Terry Mort | 352 pages | 17 Apr 2014 | Little, Brown Book Group | 9781472110923 | English | London, United Kingdom Bascom affair - Wikipedia But who, if he be called upon to face Some awful moment to which Heaven has join'd Great issues, good or bad, for humankind, Is happy as a Lover, and attired With sudden brightness like a Man inspired. In rare cases, those moments also affect the course of history. The tensions of these moments, along with the excitement, are intensified for someone in command, especially a young officer, not only because he has to make a decision with little experience to guide him, but also because he has to make it in front of his troops—men whose good opinions he values, whose loyalty he depends on, and whose lives he is responsible for. Worse yet, there rarely is much time in these situations to think the matter through or to seek counsel, assuming any is available. One of the most difficult questions a young officer ever has to answer is "What should we do, Lieutenant? To a romantic The Wrath of Cochise: The Bascom Affair and the Origins of the Apache Wars like Wordsworth, with no experience of war, the "happy warrior" greets these moments cheerfully and with confidence and inspiration. No doubt such heroes have existed. After all, Wordsworth was writing about Lord Nelson, who fit the image and made decisions that generally worked out well, for the British, at any rate.