Janine Antoni Anna Halprin Stephen Petronio

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Art in the Twenty-First Century Screening Guide: Season

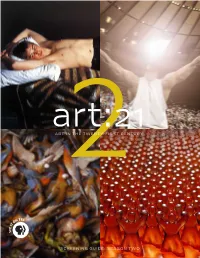

art:21 ART IN2 THE TWENTY-FIRST CENTURY SCREENING GUIDE: SEASON TWO SEASON TWO GETTING STARTED ABOUT THIS SCREENING GUIDE ABOUT ART21, INC. This screening guide is designed to help you plan an event Art21, Inc. is a non-profit contemporary art organization serving using Season Two of Art in the Twenty-First Century. This guide students, teachers, and the general public. Art21’s mission is to includes a detailed episode synopsis, artist biographies, discussion increase knowledge of contemporary art, ignite discussion, and inspire questions, group activities, and links to additional resources online. creative thinking by using diverse media to present contemporary artists at work and in their own words. ABOUT ART21 SCREENING EVENTS Public screenings of the Art:21 series engage new audiences and Art21 introduces broad public audiences to a diverse range of deepen their appreciation and understanding of contemporary art contemporary visual artists working in the United States today and and ideas. Organizations and individuals are welcome to host their to the art they are producing now. By making contemporary art more own Art21 events year-round. Some sites plan their programs for accessible, Art21 affords people the opportunity to discover their broad public audiences, while others tailor their events for particular own innate abilities to understand contemporary art and to explore groups such as teachers, museum docents, youth groups, or scholars. possibilities for new viewpoints and self-expression. Art21 strongly encourages partners to incorporate interactive or participatory components into their screenings, such as question- The ongoing goals of Art21 are to enlarge the definitions and and-answer sessions, panel discussions, brown bag lunches, guest comprehension of contemporary art, to offer the public a speakers, or hands-on art-making activities. -

Introduction to Art Making- Motion and Time Based: a Question of the Body and Its Reflections As Gesture

Introduction to Art Making- Motion and Time Based: A Question of the Body and its Reflections as Gesture. ...material action is painting that has spread beyond the picture surface. The human body, a laid table or a room becomes the picture surface. Time is added to the dimension of the body and space. - "Material Action Manifesto," Otto Muhl, 1964 VIS 2 Winter 2017 When: Thursday: 6:30 p.m. to 8:20p.m. Where: PCYNH 106 Professor: Ricardo Dominguez Email: [email protected] Office Hour: Thursday. 11:00 a.m. to Noon. Room: VAF Studio 551 (2nd Fl. Visual Art Facility) The body-as-gesture has a long history as a site of aesthetic experimentation and reflection. Art-as-gesture has almost always been anchored to the body, the body in time, the body in space and the leftovers of the body This class will focus on the history of these bodies-as-gestures in performance art. An additional objective for the course will focus on the question of documentation in order to understand its relationship to performance as an active frame/framing of reflection. We will look at modernist, contemporary and post-contemporary, contemporary work by Chris Burden, Ulay and Abramovic, Allen Kaprow, Vito Acconci, Coco Fusco, Faith Wilding, Anne Hamilton, William Pope L., Tehching Hsieh, Revered Billy, Nao Bustamante, Ana Mendieta, Cindy Sherman, Adrian Piper, Sophie Calle, Ron Athey, Patty Chang, James Luna, and the work of many other body artists/performance artists. Students will develop 1 performance action a week, for 5 weeks, for a total of 5 gestures/actions (during the first part of the class), individually or in collaboration with other students. -

ON PAIN in PERFORMANCE ART by Jareh Das

BEARING WITNESS: ON PAIN IN PERFORMANCE ART by Jareh Das Thesis submitted in fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of PhD Department of Geography Royal Holloway, University of London, 2016 1 Declaration of Authorship I, Jareh Das hereby declare that this thesis and the work presented in it is entirely my own. Where I have consulted the work of others, this is always clearly stated. Signed: Date: 19th December 2016 2 Acknowledgments This thesis is the result of the generosity of the artists, Ron Athey, Martin O’Brien and Ulay. They, who all continue to create genre-bending and deeply moving works that allow for multiple readings of the body as it continues to evolve alongside all sort of cultural, technological, social, and political shifts. I have numerous friends, family (Das and Krys), colleagues and acQuaintances to thank all at different stages but here, I will mention a few who have been instrumental to this process – Deniz Unal, Joanna Reynolds, Adia Sowho, Emmanuel Balogun, Cleo Joseph, Amanprit Sandhu, Irina Stark, Denise Kwan, Kirsty Buchanan, Samantha Astic, Samantha Sweeting, Ali McGlip, Nina Valjarevic, Sara Naim, Grace Morgan Pardo, Ana Francisca Amaral, Anna Maria Pinaka, Kim Cowans, Rebecca Bligh, Sebastian Kozak and Sabrina Grimwood. They helped me through the most difficult parts of this thesis, and some were instrumental in the editing of this text. (Jo, Emmanuel, Anna Maria, Grace, Deniz, Kirsty and Ali) and even encouraged my initial application (Sabrina and Rebecca). I must add that without the supervision and support of Professor Harriet Hawkins, this thesis would not have been completed. -

To Whom It May Concern: Nam June Paik's Wobbulator and Playful Identity

To whom it may concern: Nam June Paik©s wobbulator and playful identity Article (Published Version) Devereaux, Emile (2013) To whom it may concern: Nam June Paik's wobbulator and playful identity. Leonardo Electronic Almanac, 19 (5). pp. 22-35. ISSN 1071-4391 This version is available from Sussex Research Online: http://sro.sussex.ac.uk/id/eprint/48741/ This document is made available in accordance with publisher policies and may differ from the published version or from the version of record. If you wish to cite this item you are advised to consult the publisher’s version. Please see the URL above for details on accessing the published version. Copyright and reuse: Sussex Research Online is a digital repository of the research output of the University. Copyright and all moral rights to the version of the paper presented here belong to the individual author(s) and/or other copyright owners. To the extent reasonable and practicable, the material made available in SRO has been checked for eligibility before being made available. Copies of full text items generally can be reproduced, displayed or performed and given to third parties in any format or medium for personal research or study, educational, or not-for-profit purposes without prior permission or charge, provided that the authors, title and full bibliographic details are credited, a hyperlink and/or URL is given for the original metadata page and the content is not changed in any way. http://sro.sussex.ac.uk catalog FARAnd by LAnfranco AcEtI And omAR KhoLEIF ISSN 1071-4391 ISBNWI 978-1-906897-21-5 CATALOGd VOL 19 NO 5 LEONARDOELECTRONICALMANACE 1 This issue of LEA is a co-publication of LEA is a publication of Leonardo/ISAST. -

SCULPTURE: CONCEPTS and STRATEGIES ART 3712C (27565), 3 Credits FALL 2020 UNIVERSITY of FLORIDA

SCULPTURE: CONCEPTS AND STRATEGIES ART 3712C (27565), 3 Credits FALL 2020 UNIVERSITY OF FLORIDA COURSE INSTRUCTOR: SEAN MILLER T/R Per. 8-10 (Actual time course meets: 3:00 – 6:00PM) LOCATION: FAC B001 OFFICE HOURS: Tuesday 1 PM (By appointment and zoom only), In case of drop-off my office is located in FAC B002 CONTACT: Cell phone: (352) 215-8580 (I like phone calls please feel free to call me) EMAIL: [email protected] COURSE BLOG: ufconceptsandstrategies.blogspot.com INFORMATION ABOUT SCULPTURE PROGRAM: UF Sculpture Blog: http://ufsculptureprogram.blogspot.com UF Sculpture Info https://arts.ufl.edu/academics/art-and-art-history/programs/studio- art/sculpture/overview/ @uf.sculpture on Instagram FINAL DATE: 12/17/2020 @ 10:00 AM - 12:00 PM We will be meeting exclusively online For tHe First 3 weeks oF class. Please do not come to FAC B1 or Woodshop during tHis period oF time. COURSE DESCRIPTION In Concepts and Strategies, we will learn about the history of sculpture and the expanded field and highlight innovative contemporary ideas in sculpture. We will experiment with conceptual and hands-on approaches used by a diverse range of artists. This course will challenge students to critically examine various sculptural methods, analyze their own creatiVe processes, and produce work utilizing these techniques. Participants in the course will focus on sculpture as it relates to post-studio practice, ephemeral art, interdisciplinary thinking, performance, and temporal site- specific art production within the realm of sculpture. The course is designed to be taken largely online to accommodate the limitations caused by the pandemic. -

Jennifer Allora & Guillermo Calzadilla Janine Antoni Chris Barr Louise

Jennifer Allora & Guillermo Calzadilla Janine Antoni Chris Barr Louise Bourgeois Luis Camnitzer Anne Collier Elsewhere Tracey Emin Harrell Fletcher & Miranda July Hadassa Goldvicht & Anat Vovnoboy Felix Gonzalez-Torres Sarah Gotowka Mona Hatoum Sharon Hayes Jim Hodges Tad Hozumi Emily Jacir Chris Johanson Antonio Vega Macotela Lynne McCabe Laurel Nakadate Rivane Neuenschwander Yoko Ono Dario Robleto Gregory Sale Kateřina Šedá Frances Stark Julianne Swartz Lee Walton Gillian Wearing CONTENTS ! Love Letters to Janine Antoni, Hadassa Goldvicht, Miranda July, Frances Stark Foreword Emily Kass Th#nk You Claire Schneider Love !s ! Str!te"ic Impulse + &''#, Claire Schneider !3 Art !nd Eros in the Sixties + &''#, Jonathan D. Katz "# -.%/' $) 0(& &1($2$0$.) Touch Gift Service L#n$u#$e Time Claire Schneider #" Artist Entries by Jennie Carlisle, Emily Mangione, Annemarie Sawkins, Claire Schneider, Lucie Steinberg, Amy White #6 The Procedures of Love + &''#, Michael Hardt !6! Lun"e for Love !s if It Were Air + &''#, Dario Robleto !66 K#teřin# Šed% + $)0&34$&- Claire Schneider !#$ Gre$or& S#le + $)0&34$&- Claire Schneider !#9 Messin" with Mister In-Between: Instructions from the Archives of Love + &''#, Rebecca Zorach !89 L#urel N#k#d#te + $)0&34$&- Claire Schneider $00 Wh# Not More Love? + &''#, Shannon Jackson $0# Becomin" Love + &''#, Lynne McCabe $!# Art !nd A"!pe + &''#, Carol Becker $$! Imperson!l Love?: Contempor!r# Art !nd Atmospheric Medi! + &''#, James J. Hodge $$# -.%*' .) ".4& By Chris Barr "6, Yoko Ono #%, Sarah Gotowka !60, Antonio Vega Macotela !#!, Tracey Emin !88, Tad Hozumi !99, Hadassa Goldvicht $06, Rivane Neuenschwander $$0, Julianne Swartz $$", Lee Walton $$6, Harrell Fletcher $3" Exhibition Checklist with Image Credits Im#$e/'eproduction Credits Contributors Exhibition Lenders Ackl#nd N#tion#l Advisor& Bo#rd . -

Art Works Grants

National Endowment for the Arts — December 2014 Grant Announcement Art Works grants Discipline/Field Listings Project details are as of November 24, 2014. For the most up to date project information, please use the NEA's online grant search system. Art Works grants supports the creation of art that meets the highest standards of excellence, public engagement with diverse and excellent art, lifelong learning in the arts, and the strengthening of communities through the arts. Click the discipline/field below to jump to that area of the document. Artist Communities Arts Education Dance Folk & Traditional Arts Literature Local Arts Agencies Media Arts Museums Music Opera Presenting & Multidisciplinary Works Theater & Musical Theater Visual Arts Some details of the projects listed are subject to change, contingent upon prior Arts Endowment approval. Page 1 of 168 Artist Communities Number of Grants: 35 Total Dollar Amount: $645,000 18th Street Arts Complex (aka 18th Street Arts Center) $10,000 Santa Monica, CA To support artist residencies and related activities. Artists residing at the main gallery will be given 24-hour access to the space and a stipend. Structured as both a residency and an exhibition, the works created will be on view to the public alongside narratives about the artists' creative process. Alliance of Artists Communities $40,000 Providence, RI To support research, convenings, and trainings about the field of artist communities. Priority research areas will include social change residencies, international exchanges, and the intersections of art and science. Cohort groups (teams addressing similar concerns co-chaired by at least two residency directors) will focus on best practices and develop content for trainings and workshops. -

EDUCATION University Studies 2002 M.F.A. in Imaging and Digital Arts At

EDUCATION University Studies 2002 M.F.A. in Imaging and Digital Arts at University of Maryland, Baltimore County (U.M.B.C.), MD, U.S.A. Thesis Chair: art critic Kathy O’Dell. 1999 M.F.A. in Art History/Studio Arts at Federal University of Rio de Janeiro, Brazil. Thesis Chair: art critic Paulo Venâncio Filho. 1993 B.F.A. in Painting at Federal University of Rio de Janeiro, Brazil. Residencies 2007 "Summer Residency: Installation and New Media Art," School of Visual Arts, New York, NY, U.S.A. Faculty: Ofri Cnaani, Steve DeFrank, Ward Shelley, and Jil Weinstock. 2002 Skowhegan School of Painting and Sculpture, Skowhegan, ME, U.S.A. Faculty: Nayland Blake, Tania Bruguera, Rackstraw Downes, Amy Goodman, Geoffrey Hendricks, Whitfield Lovell,Iñigo Manglano–Ovalle, Melissa Meyer, Robert Storr, Kay WalkingStick and Betty Woodman. 1995 “Advanced Studies in Painting,” School of Visual Arts of Parque Lage, Rio de Janeiro, Brazil. Faculty: Beatriz Milhazes, Daniel Senise, Kathie van Shaepenberg and Charles Watson. 1994 "The London Project 94." Workshops in art history/studio art, London, England. Faculty: Ricardo Basbaum, Milton Machado, Charles Watson, among others. 1 EXHIBITIONS One-Person Exhibitions 2012 Crimes Against Love – President’s Gallery / John Jay College, New York, NY. 2012 Uma Coisa Into Another – Hand Arts Center / Stetson University, FL - a collaboration with poet Terri Witek. 2010 “but here all dreams equal distance,” (a show of works & a live performance in collaboration with poet Terri Witek) at The Faulconer Gallery / Grinnell College, Iowa. Curated by Lesley Wright. 2009 “Big Bronze Statues,” Le Petite Versailles, New York, NY. -

Course Schedule

Printed on: Jan 3, 2019 at 5:19 PM Course Schedule Undergraduate : Spring 2019 : Art and Technology Course Schedule AT-110-01 Introduction to Robotics Kal Spelletich F 9:00AM - 11:45AM Room: 105 F 1:00PM - 3:45PM Room: 105 This course provides an introduction to building robotic, kinetic and interactive art. Students will design and fabricate working robotic machine systems preparing students for an interdisciplinary future as technology and robotic artists.The course explores Human-Robot Interaction with a desire to disruptively redefine how communities and individuals can make sense of their context through the use of robotic technologies. This class is a hands-on approach to learning using technology as inspiration. The course surveys, researches and examines robotic art and it's historic and interdisciplinary issues. Prerequisite: none Satisfies: Introduction to Art &Technology II, AT Electronic Distribution, Art &Technology Elective, Studio Elective, Media Breadth, Design &Technology Elective AT-120-01 Physical Computing for Artists Cristobal Martinez M W 9:00AM - 11:45AM Room: DMS2 This course focuses on physical computing geared toward artistic practice. During this intensive students will develop computer-programing skills and techniques using Max7 and the Arduino integrated development environment. Additionally, students will learn to design and build simple circuits for creating physical computing systems that integrate the digital and physical world together. In other words, this course is learning how to use technologies to sense the physical world, as well as how to use the physical world to influence the behavior of audio, visual, haptic, and robotic media. In this course students will acquire entry-level knowledge of how to apply human interactivity and environmental conditions to the development of artistic installations and interfaces. -

CHANGING the EQUATION ARTTABLE CHANGING the EQUATION WOMEN’S LEADERSHIP in the VISUAL ARTS | 1980 – 2005 Contents

CHANGING THE EQUATION ARTTABLE CHANGING THE EQUATION WOMEN’S LEADERSHIP IN THE VISUAL ARTS | 1980 – 2005 Contents 6 Acknowledgments 7 Preface Linda Nochlin This publication is a project of the New York Communications Committee. 8 Statement Lila Harnett Copyright ©2005 by ArtTable, Inc. 9 Statement All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted Diane B. Frankel by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording, or information retrieval system, without written permission from the publisher. 11 Setting the Stage Published by ArtTable, Inc. Judith K. Brodsky Barbara Cavaliere, Managing Editor Renée Skuba, Designer Paul J. Weinstein Quality Printing, Inc., NY, Printer 29 “Those Fantastic Visionaries” Eleanor Munro ArtTable, Inc. 37 Highlights: 1980–2005 270 Lafayette Street, Suite 608 New York, NY 10012 Tel: (212) 343-1430 [email protected] www.arttable.org 94 Selection of Books HE WOMEN OF ARTTABLE ARE CELEBRATING a joyous twenty-fifth anniversary Acknowledgments Preface together. Together, the members can look back on years of consistent progress HE INITIAL IMPETUS FOR THIS BOOK was ArtTable’s 25th Anniversary. The approaching milestone set T and achievement, gained through the cooperative efforts of all of them. The us to thinking about the organization’s history. Was there a story to tell beyond the mere fact of organization started with twelve members in 1980, after the Women’s Art Movement had Tsustaining a quarter of a century, a story beyond survival and self-congratulation? As we rifled already achieved certain successes, mainly in the realm of women artists, who were through old files and forgotten photographs, recalling the organization’s twenty-five years of professional showing more widely and effectively, and in that of feminist art historians, who had networking and the remarkable women involved in it, a larger picture emerged. -

JANINE ANTONI Born 1964, Freeport, Bahamas Lives and Works in New York, NY

JANINE ANTONI Born 1964, Freeport, Bahamas Lives and works in New York, NY EDUCATION 1989, MFA Sculpture (Honors), Rhode Island School of Design, Providence, RI 1986, BA, Sarah Lawrence College, Bronxville, NY AWARDS 2014, Anonymous Was a Woman Award, New York, NY 2014, Project Grant (in collaboration with the Fabric Workshop and Museum), Pew Center for Arts and Heritage, Philadelphia, PA 2012, Creative Capital Grant 2011, John Simon Guggenheim Memorial Foundation Award 2004, Artes Mundi, Wales International Visual Art Prize (nominee) 1999, New Media Award, Institute for Contemporary Art/Boston, Boston, MA 1999, Larry Aldrich Foundation Award 1998, MacArthur Fellowship 1998, Painting and Sculpture Grant, Joan Mitchell Foundation, Inc. 1996, Glen Dimplex Artists Award, Irish Museum of Modern Art, Dublin, Ireland SELECTED SOLO EXHIBITIONS 2020-2021 Janine Antoni and Stephen Petronio: Honey Baby, Locust Projects, Miami, FL 2019 Janine Antoni and Anna Halprin: Paper Dance, The Contemporary, Austin, TX Janine Antoni: I am fertile ground, Green-Wood Cemetery Catacombs, Brooklyn, NY [temporary installation] 2018 Janine Antoni: Moor and Touch, Accelerator, Stockholm University, Stockholm, Sweden 2017 Janine Antoni and Stephen Petronio: Entangle, Frances Young Tang Teaching Museum and Art Gallery at Skidmore College, Saratoga Springs, NY 2016 Ally, The Fabric Workshop and Museum, Philadelphia, PA* Janine Antoni and Stephen Petronio: Honey Baby, Sheppard Contemporary Art Gallery, University of Nevada, Reno, Nevada 2015 Incubator: Janine Antoni -

1/14/2011 the San Jose Museum of Art Art Collections in Dallas And

1/14/2011 The San Jose Museum of Art Art Collections in Dallas and Fort Worth, Texas Wednesday April 27th – Sunday May 1st 2011 Draft Itinerary Day One: Wednesday April 27th 2011 Individual arrival and check in at the Ritz-Carlton Dallas. The Ritz-Carlton Dallas is a stylish, contemporary downtown Dallas hotel–where glamour, graciousness and the Texas spirit meet. Opened in August 2007, The Ritz-Carlton Dallas is ideally located in the chic, picturesque enclave of uptown Dallas. Everyone will have access to the club level on floor 7 which includes food and beverage service five times daily in a private club lounge. (2121 McKinney Avenue, Dallas, Texas 75201 (214) 922-0200). 7:00 p.m. Please gather in the lobby of the Ritz Carlton Dallas to meet Lisa Hahn, President of Art Horizons International as well as your art and architectural historian who will provide insightful commentary along the way. 7:15 p.m. Depart by bus for a welcome dinner at Restaurant Five Sixty. 7:30 p.m. Enjoy a welcome dinner at Five Sixty, a Wolfgang Puck restaurant. Wolfgang's incomparable Asian-influenced cuisine and award-winning service rises 560 feet above the ground atop Reunion Tower. Day Two: Thursday April 28th 2011 Dallas Enjoy breakfast at the Ritz Carlton Dallas club level on floor 7. (Breakfast is served from 7:00am-10:00am in the club lounge). 8:45 a.m. Gather in the lobby. 9:00 a.m. Depart by private motorcoach for a private collection. 9:15 a.m. Visit the private art collection and home of one of Dallas’s most important cultural leaders.