Regulatory Obsolescence Through Technological Change in Oil and Gas Extraction

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Unconventional Gas and Oil in North America Page 1 of 24

Unconventional gas and oil in North America This publication aims to provide insight into the impacts of the North American 'shale revolution' on US energy markets and global energy flows. The main economic, environmental and climate impacts are highlighted. Although the North American experience can serve as a model for shale gas and tight oil development elsewhere, the document does not explicitly address the potential of other regions. Manuscript completed in June 2014. Disclaimer and copyright This publication does not necessarily represent the views of the author or the European Parliament. Reproduction and translation of this document for non-commercial purposes are authorised, provided the source is acknowledged and the publisher is given prior notice and sent a copy. © European Union, 2014. Photo credits: © Trueffelpix / Fotolia (cover page), © bilderzwerg / Fotolia (figure 2) [email protected] http://www.eprs.ep.parl.union.eu (intranet) http://www.europarl.europa.eu/thinktank (internet) http://epthinktank.eu (blog) Unconventional gas and oil in North America Page 1 of 24 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY The 'shale revolution' Over the past decade, the United States and Canada have experienced spectacular growth in the production of unconventional fossil fuels, notably shale gas and tight oil, thanks to technological innovations such as horizontal drilling and hydraulic fracturing (fracking). Economic impacts This new supply of energy has led to falling gas prices and a reduction of energy imports. Low gas prices have benefitted households and industry, especially steel production, fertilisers, plastics and basic petrochemicals. The production of tight oil is costly, so that a high oil price is required to make it economically viable. -

Statoil-2015-Statutory-Report.Pdf

2015 Statutory report in accordance with Norwegian authority requirements © Statoil 2016 STATOIL ASA BOX 8500 NO-4035 STAVANGER NORWAY TELEPHONE: +47 51 99 00 00 www.statoil.com Cover photo: Øyvind Hagen Statutory report 2015 Board of directors report ................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................ 3 The Statoil share ............................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................ 4 Our business ..................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................... 4 Group profit and loss analysis .................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................... 6 Cash flows ........................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................ -

Unconventional Oil Resources Exploitation: a Review

Acta Montanistica Slovaca Volume 21 (2016), number 3, 247-257 Unconventional oil resources exploitation: A review Šárka Vilamová 1, Marian Piecha 2 and Zden ěk Pavelek 3 Unconventional crude oil sources are geographically extensive and include the tar sands of the Province of Alberta in Canada, the heavy oil belt of the Orinoco region of Venezuela and the oil shales of the United States, Brazil, India and Malagasy. High production costs and low oil prices have hitherto inhibited the inclusion of unconventional oil resources in the world oil resource figures. In the last decade, developing production technologies, coupled with the higher market value of oil, convert large quantities of unconventional oil into an effective resource. From the aspect of quantity and technological and economic recoverability are actually the most important tar sands. Tar sands can be recovered via surface mining or in-situ collection techniques. This is an up-stream part of exploitation process. Again, this is more expensive than lifting conventional petroleum, but for example, Canada's Athabasca (Alberta) Tar Sands is one example of unconventional reserve that can be economically recoverable with the largest surface mining machinery on the waste landscape with important local but also global environmental impacts. The similar technology of up-stream process concerns oil shales. The downstream part process of solid unconventional oil is an energetically difficult process of separation and refining with important increasing of additive carbon production and increasing of final product costs. In the region of Central Europe is estimated the mean volume of 168 million barrels of technically recoverable oil and natural gas liquids situated in Ordovician and Silurian age shales in the Polish- Ukrainian Foredeep basin of Poland. -

Trends in U.S. Oil and Natural Gas Upstream Costs

Trends in U.S. Oil and Natural Gas Upstream Costs March 2016 Independent Statistics & Analysis U.S. Department of Energy www.eia.gov Washington, DC 20585 This report was prepared by the U.S. Energy Information Administration (EIA), the statistical and analytical agency within the U.S. Department of Energy. By law, EIA’s data, analyses, and forecasts are independent of approval by any other officer or employee of the United States Government. The views in this report therefore should not be construed as representing those of the Department of Energy or other federal agencies. U.S. Energy Information Administration | Trends in U.S. Oil and Natural Gas Upstream Costs i March 2016 Contents Summary .................................................................................................................................................. 1 Onshore costs .......................................................................................................................................... 2 Offshore costs .......................................................................................................................................... 5 Approach .................................................................................................................................................. 6 Appendix ‐ IHS Oil and Gas Upstream Cost Study (Commission by EIA) ................................................. 7 I. Introduction……………..………………….……………………….…………………..……………………….. IHS‐3 II. Summary of Results and Conclusions – Onshore Basins/Plays…..………………..…….… -

Oil and Gas Technologies Supplemental Information

Quadrennial Technology Review 2015 Chapter 7: Advancing Systems and Technologies to Produce Cleaner Fuels Supplemental Information Oil and Gas Technologies Subsurface Science, Technology, and Engineering U.S. DEPARTMENT OF ENERGY Quadrennial Technology Review 2015 Oil and Gas Technologies Chapter 7: Advancing Systems and Technologies to Produce Cleaner Fuels Oil and Gas in the Energy Economy of the United States Fossil fuel resources account for 82% of total U.S. primary energy use because they are abundant, have a relatively low cost of production, and have a high energy density—enabling easy transport and storage. The infrastructure built over decades to supply fossil fuels is the world’s largest enterprise with the largest market capitalization. Of fossil fuels, oil and natural gas make up 63% of energy usage.1 Across the energy economy, the source and mix of fuels used across these sectors is changing, particularly the rapid increase in natural gas production from unconventional resources for electricity generation and the rapid increase in domestic production of shale oil. While oil and gas fuels are essential for the United States’ and the global economy, they also pose challenges: Economic: They must be delivered to users and the markets at competitive prices that encourage economic growth. High fuel prices and/or price volatility can impede this progress. Security: They must be available to the nation in a reliable, continuous way that supports national security and economic needs. Disruption of international fuel supply lines presents a serious geopolitical risk. Environment: They must be supplied and used in ways that have minimal environmental impacts on local, national, and global ecosystems and enables their sustainability. -

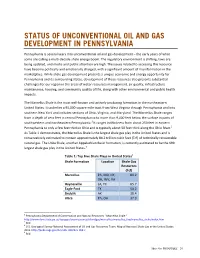

Status of Unconventional Oil and Gas Development in Pennsylvania

STATUS OF UNCONVENTIONAL OIL AND GAS DEVELOPMENT IN PENNSYLVANIA Pennsylvania is several years into unconventional oil and gas development – the early years of what some are calling a multi-decade shale energy boom. The regulatory environment is shifting, laws are being updated, and media and public attention are high. The issues related to accessing this resource have become politically and emotionally charged, with a significant amount of misinformation in the marketplace. While shale gas development presents a unique economic and energy opportunity for Pennsylvania and its surrounding states, development of these resources also presents substantial challenges for our region in the areas of water resources management, air quality, infrastructure maintenance, housing, and community quality of life, along with other environmental and public health impacts. The Marcellus Shale is the most well-known and actively producing formation in the northeastern United States. It underlies a 95,000-square-mile tract from West Virginia through Pennsylvania and into southern New York and includes sections of Ohio, Virginia, and Maryland. The Marcellus Shale ranges from a depth of zero feet in central Pennsylvania to more than 9,000 feet below the surface in parts of southwestern and northeastern Pennsylvania.1 It ranges in thickness from about 250 feet in eastern Pennsylvania to only a few feet thick in Ohio and is typically about 50 feet thick along the Ohio River.2 As Table 1 demonstrates, the Marcellus Shale is the largest shale gas play in the United States and is conservatively estimated to contain approximately 84.2 trillion cubic feet (Tcf) of technically recoverable natural gas. -

The Exxonmobil-Xto Merger: Impact on U.S

THE EXXONMOBIL-XTO MERGER: IMPACT ON U.S. ENERGY MARKETS HEARING BEFORE THE SUBCOMMITTEE ON ENERGY AND ENVIRONMENT OF THE COMMITTEE ON ENERGY AND COMMERCE HOUSE OF REPRESENTATIVES ONE HUNDRED ELEVENTH CONGRESS SECOND SESSION JANUARY 20, 2010 Serial No. 111–91 ( Printed for the use of the Committee on Energy and Commerce energycommerce.house.gov U.S. GOVERNMENT PRINTING OFFICE 76–003 WASHINGTON : 2012 For sale by the Superintendent of Documents, U.S. Government Printing Office Internet: bookstore.gpo.gov Phone: toll free (866) 512–1800; DC area (202) 512–1800 Fax: (202) 512–2104 Mail: Stop IDCC, Washington, DC 20402–0001 VerDate Mar 15 2010 00:51 Nov 06, 2012 Jkt 076003 PO 00000 Frm 00001 Fmt 5011 Sfmt 5011 E:\HR\OC\A003.XXX A003 pwalker on DSK7TPTVN1PROD with HEARING COMMITTEE ON ENERGY AND COMMERCE HENRY A. WAXMAN, California, Chairman JOHN D. DINGELL, Michigan JOE BARTON, Texas Chairman Emeritus Ranking Member EDWARD J. MARKEY, Massachusetts RALPH M. HALL, Texas RICK BOUCHER, Virginia FRED UPTON, Michigan FRANK PALLONE, JR., New Jersey CLIFF STEARNS, Florida BART GORDON, Tennessee NATHAN DEAL, Georgia BOBBY L. RUSH, Illinois ED WHITFIELD, Kentucky ANNA G. ESHOO, California JOHN SHIMKUS, Illinois BART STUPAK, Michigan JOHN B. SHADEGG, Arizona ELIOT L. ENGEL, New York ROY BLUNT, Missouri GENE GREEN, Texas STEVE BUYER, Indiana DIANA DEGETTE, Colorado GEORGE RADANOVICH, California Vice Chairman JOSEPH R. PITTS, Pennsylvania LOIS CAPPS, California MARY BONO MACK, California MICHAEL F. DOYLE, Pennsylvania GREG WALDEN, Oregon JANE HARMAN, California LEE TERRY, Nebraska TOM ALLEN, Maine MIKE ROGERS, Michigan JANICE D. SCHAKOWSKY, Illinois SUE WILKINS MYRICK, North Carolina CHARLES A. -

The Shale Revolution and OPEC Potential Economic Implications of Shale Oil for OPEC and Member Countries

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Southern Methodist University Southern Methodist University SMU Scholar The Larrie and Bobbi Weil Undergraduate Research Central University Libraries Award Documents 2014 The hS ale Revolution and OPEC: Potential Economic Implications of Shale Oil for OPEC and Member Countries Kyle Lemons Southern Methodist University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://scholar.smu.edu/weil_ura Part of the Economics Commons Recommended Citation Lemons, Kyle, "The hS ale Revolution and OPEC: Potential Economic Implications of Shale Oil for OPEC and Member Countries" (2014). The Larrie and Bobbi Weil Undergraduate Research Award Documents. 5. https://scholar.smu.edu/weil_ura/5 This document is brought to you for free and open access by the Central University Libraries at SMU Scholar. It has been accepted for inclusion in The Larrie and Bobbi Weil Undergraduate Research Award Documents by an authorized administrator of SMU Scholar. For more information, please visit http://digitalrepository.smu.edu. The Shale Revolution and OPEC Potential Economic Implications of Shale Oil for OPEC and Member Countries By Kyle Lemons Southern Methodist University Fall, 2013 Table of Contents: I. Introduction II. Methodology and Research Design III. Contextual Framework a. Current Trends in Crude Oil Demand b. Recent History of OPEC i. Export Patterns ii. Market Penetration IV. Shale Oil a. History and Properties of Shale Oil b. Location of Shale Oil Reserves c. Potential of Shale Oil Development V. Current and Prospective Impacts of Shale Oil on Segmented OPEC Market Shares a. -

Upstream Break-Out: Longer Term Investments

BP 2011 Results and Strategy Presentation Upstream break-out: Longer term investments Upstream break-out 0 200km Longer term investments play to our 0 100kmstrengths Mike Daly: EVP, Exploration Andy Hopwood: EVP, Strategy & Integration 0 200km 0 200km 0 200km 0 250km 0 200km1 Good afternoon. I’m Mike Daly, Executive Vice President, Exploration and together with my colleague Andy Hopwood, Executive Vice President, Strategy and Integration, we will take you through some detail about BP’s longer term future. Bob spoke earlier about our resource base and the upcoming projects. I will deal with our exploration and appraisal portfolios. Andy will then cover our position in unconventionals – and how we are adding value to our major gas positions down the value chain. But first a word about BP’s resource base in general. 1 BP 2011 Results and Strategy Presentation Upstream break-out: Longer term investments Cautionary statement Forward-looking statements - cautionary statement This presentation and the associated slides and discussion contain forward-looking statements, particularly those regarding: expected increases in investment in exploration and upstream drilling and production; anticipated improvements and increases, and sources and timing thereof, in pre-tax returns, operating cash flow and margins, including generating around 50% more annually in operating cashflow by 2014 versus 2011 at US$100/bbl; divestment plans, including the anticipated timing for completion of and final proceeds from the disposition of certain BP assets; the expected -

Unconventional and Conventional Oil Production Impacts on Oil Price

lobal f G E o co l n Ali et al., J Glob Econ 2018, 6:1 a o n m r DOI: 10.4172/2375-4389.1000286 u i c o s J $ Journal of Global Economics ISSN: 2375-4389 Research Article OpenOpen Access Access Unconventional and Conventional Oil Production Impacts on Oil Price: Lessons Learnt with Glance to the Future Sawsan Ahmed Ali*, Abhijit Suboyin and Hadi Bel Haj Department of Economics, Khalifa University, Al Zafranah, Abu Dhabi, United Arab Emirates Abstract Energy is not a traditional commodity where low prices is always good news! It might be good for some, but definitely, not the case for many. Energy resources including, fossil fuels and renewables, have a significant impact on our day to day activities and they have been prime contributors to our lives retention, advancements and upheaval of the world economy at large. As a result, oil has not only played the role of the master commodity on a financial and economical level, but has also extended its supreme impact to the social, sociopolitical and geopolitical aspects of the modern world. However, it is peculiar to note that even with this significance, the oil industry has been experiencing various economic shocks over the past decades. Such shocks have directly been reflected in oil price fluctuations within a dynamic and short timeframe. With the OPEC and non-OPEC production fluctuations against consistent economic growth, worldwide geopolitical conflicts and the ongoing competition between conventional and unconventional oil reserves, the swings in oil prices have become a phenomenon which is worth understanding and analyzing in order to prospect its future trends on the long run. -

Peak Oil and the Evolving Strategies of Oil Importing and Exporting Countries Facing the Hard Truth About an Import Decline for the OECD Countries

JOINT TRANSPORT RESEARCH CENTRE Discussion Paper No. 2007-17 December 2007 Peak Oil and the Evolving Strategies of Oil Importing and Exporting Countries Facing the hard truth about an import decline for the OECD countries Kjell ALEKLETT Uppsala University Uppsala, Sweden SUMMARY ABSTRACT ................................................................................................................... 4 1. INTRODUCTION .................................................................................................... 5 1.1 Mission ............................................................................................................. 5 1.2 Major articles by Uppsala Hydrocarbon Depletion Study Groupe. .................. 6 1.3 Peak oil and today’s society ............................................................................. 8 1.4 References 1. ................................................................................................. 11 2. FUTURE DEMAND FOR OIL ............................................................................... 13 2.1 Future oil demand forecasts by IEA and EIA ................................................. 13 2.2 Oil intensity driven demand ............................................................................ 13 2.4 References 2 .................................................................................................. 17 3. HOW MUCH OIL HAVE WE FOUND AND WHEN DID WE FIND IT? ................ 18 3.1 Resources and reserves ............................................................................... -

A Discussion Paper on the Oil Sands: Challenges and Opportunities

A discussion paper on the oil sands: challenges and opportunities Kevin Birn* and Paul Khanna Special thanks to CanmetENERGY in Devon, Alberta for their advice and contribution. Natural Resources Canada 580 Booth Street, Ottawa, ON, K1A 0E4, Canada Abstract Key words: Petroleum Energy, Oil Sands, Environmental Impacts, Heavy Oil, Unconventional Oil The oil sands have become a significant source of secure energy supply and a major economic driver for Canada. As production in the oil sands expands so too has concern about the effects of development on communities, water, land, and air. This paper aims to provide a basis for an informed discussion about the oil sands by examining the current challenges facing development and by reviewing the central issues, both positive and negative facing the industry. This paper isn‘t meant to provide an exhaustive list of all potential impacts associated with oil sands development or document the oil sands regulatory regime. Outline Introduction....................................................................................................................... 3 The Resource ..................................................................................................................... 5 The History........................................................................................................................ 6 Oil Sands Operations........................................................................................................ 8 Surface Mining Operations..........................................................................................