Alexandra Park: Dynamics of Redevelopment

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Parkdale Community Benefits Framework Guide for Development Without Displacement

Parkdale People's Economy Full Report Parkdale Community Economy November 2018 Development (PCED) Planning Project Parkdale Community Benefits Framework Guide for Development without Displacement Equitable targets for policymakers, political representatives, developers, investors, and community advocates. Version 1 Table of Contents 2 Acknowledgments 3 1. Introduction 6 1.1. What's in it for Parkdale? 6 1.2. What is the Purpose of this Framework? 8 1.3. What are Community Benefits? 8 1.4. What is Our Vision? 9 1.5. How was this Framework Created? 10 1.6. What is the Parkdale People's Economy? 12 1.7. How to Use this Framework? 12 2. Community Benefits Demands: Summary 15 2.1. Community Benefits Demands and Targets 15 3. Equitable Process 20 3.1. Accessible Consultations 21 3.2. Equity Impact Assessment 21 3.3. Community Planning Board 22 3.4. Community Benefits Agreements 22 4. Affordable Housing 24 4.1. Building Shared Language 25 4.2. Affordable Housing Targets 26 4.3. Adequacy and Accessibility 30 4.4. How to Achieve Targets: Community 31 4.5. How to Achieve Targets: Policy 31 5. Affordable Commercial 34 5.1. Affordable Commercial Targets 35 5.2. How to Achieve Targets: Policy 36 5.3. How to Achieve Targets: Community 38 6. Decent Work 40 6.1. Construction, Renovation, and Retrofit 41 6.2. Housing Operations 42 6.3. Business Operations 42 6.4. Wraparound Supports 43 6.5. Mandating Social Procurement 44 6.6. Employment and Industrial Lands 44 6.7. Promoting a Cultural Shift around Decent Work 44 7. -

Still Hip: National Historic Sites National Historic Sites Urban Walks: Toronto

� � � � � � � � AVE EGLINTON AVE EGLINTON CH AVE RD CH AVE CH MT PLEASANT RD PLEASANT CH MT DAVISVILLE RUE YONGE ST BARTHURST ST BARTHURST AVE ST CLAIR AVE ST CLAIR RUE RUE Still Hip: NationalBATHURST RUE BLOOR Historic ST SPADINA ST GEORGE Sites BAY BLOOR-YONGE RUE BLOOR ST SHERBOURNE RUE National Historic Sites Urban Walks: Toronto RUE MUSEUM RUE WELLESLEY 5 QUEEN’S PK. COLLEGE AUTOROUTE MACDONALD CARTIER FWY RUE BEVERLEY ST RUE BEVERLEY 4 IO CH KINGSTON RD AVE AVE WOODBINE AVE RUE YONGE ST RUE DUNDAS ST LAKE ONTAR RUE QUEEN ST E AVE GLADSTONE AVE GLADSTONE AVE ST PATRICK DUNDAS LAC ONTARIO RUE DUFFERIN ST RUE QUEEN ST 6 RUE KING ST RUE BARTHURST ST RUE BARTHURST 7 OSGOODE QUEEN 3 ST ANDREW KING UNION 8 2 1 ������������� ������������ Gouinlock Buildings / Early Exhibition Buildings Think that historic sites are boring? Think again. John Street Roundhouse (Canadian Pacific) Toronto is filled with National Historic Sites that are still hip and happening! Royal Alexandra Theatre Many of the sites, have been carefully restored while integrating creative Kensington Market architectural design and adaptive re-uses. Finding new uses for heritage sites is not only trendy, it’s also part of an eco-friendly approach to re-using existing Eaton’s 7th Floor Auditorium and Round Room materials and buildings. Massey Hall Plan your weekend around Toronto’s hip and happening National Historic Elgin and Winter Garden Theatres Sites! Visit these hip historic sites and find out which one is now an upscale Gooderham and Worts Distillery dance club, which Art Deco Auditorium now hosts exclusive VIP events, which theatre’s ceiling is covered with beech tree branches, and which historic site now produces beer! Still Hip: National Historic Sites National Historic Sites Urban Walks: Toronto 1. -

Now Until Jun 16. NXNE Music Festival. Yonge and Dundas. Nxne

hello ANNUAL SUMMER GUIDE Jun 14-16. Taste of Little Italy. College St. Jun 21-30. Toronto Jazz Festival. from Bathurst to Shaw. tolittleitaly.com Featuring Diana Ross and Norah Jones. hello torontojazz.com Now until Jun 16. NXNE Music Festival. Jun 14-16. Great Canadian Greek Fest. Yonge and Dundas. nxne.com Food, entertainment and market. Free. Jun 22. Arkells. Budweiser Stage. $45+. Exhibition Place. gcgfest.com budweiserstage.org Now until Jun 23. Luminato Festival. Celebrating art, music, theatre and dance. Jun 15-16. Dragon Boat Race Festival. Jun 22. Cycle for Sight. 125K, 100K, 50K luminatofestival.com Toronto Centre Island. dragonboats.com and 25K bike ride supporting the Foundation Fighting Blindness. ffb.ca Jun 15-Aug 22. Outdoor Picture Show. Now until Jun 23. Pride Month. Parade Jun Thursday nights in parks around the city. Jun 22. Pride and Remembrance Run. 23 at 2pm on Church St. pridetoronto.com topictureshow.com 5K run and 3K walk. priderun.org Now until Jun 23. The Book of Mormon. Jun 16. Father’s Day Heritage Train Ride Jun 22. Argonauts Home Opener vs. The musical. $35+. mirvish.com (Uxbridge). ydhr.ca Hamilton Tiger-Cats. argonauts.ca Now until Jun 27. Toronto Japanese Film Jun 16. Father’s Day Brunch Buffet. Craft Jun 23. Brunch in the Vineyard. Wine Festival (TJFF). $12+. jccc.on.ca Beer Market. craftbeermarket.ca/Toronto and food pairing. Jackson-Triggs Winery. $75. niagarawinefestival.com Now until Aug 21. Fresh Air Fitness Jun 17. The ABBA Show. $79+. sonycentre.ca Jun 25. Hugh Jackman. $105+. (Mississauga). Wednesdays at 7pm. -

923466Magazine1final

www.globalvillagefestival.ca Global Village Festival 2015 Publisher: Silk Road Publishing Founder: Steve Moghadam General Manager: Elly Achack Production Manager: Bahareh Nouri Team: Mike Mahmoudian, Sheri Chahidi, Parviz Achak, Eva Okati, Alexander Fairlie Jennifer Berry, Tony Berry Phone: 416-500-0007 Email: offi[email protected] Web: www.GlobalVillageFestival.ca Front Cover Photo Credit: © Kone | Dreamstime.com - Toronto Skyline At Night Photo Contents 08 Greater Toronto Area 49 Recreation in Toronto 78 Toronto sports 11 History of Toronto 51 Transportation in Toronto 88 List of sports teams in Toronto 16 Municipal government of Toronto 56 Public transportation in Toronto 90 List of museums in Toronto 19 Geography of Toronto 58 Economy of Toronto 92 Hotels in Toronto 22 History of neighbourhoods in Toronto 61 Toronto Purchase 94 List of neighbourhoods in Toronto 26 Demographics of Toronto 62 Public services in Toronto 97 List of Toronto parks 31 Architecture of Toronto 63 Lake Ontario 99 List of shopping malls in Toronto 36 Culture in Toronto 67 York, Upper Canada 42 Tourism in Toronto 71 Sister cities of Toronto 45 Education in Toronto 73 Annual events in Toronto 48 Health in Toronto 74 Media in Toronto 3 www.globalvillagefestival.ca The Hon. Yonah Martin SENATE SÉNAT L’hon Yonah Martin CANADA August 2015 The Senate of Canada Le Sénat du Canada Ottawa, Ontario Ottawa, Ontario K1A 0A4 K1A 0A4 August 8, 2015 Greetings from the Honourable Yonah Martin Greetings from Senator Victor Oh On behalf of the Senate of Canada, sincere greetings to all of the organizers and participants of the I am pleased to extend my warmest greetings to everyone attending the 2015 North York 2015 North York Festival. -

History of Ethnic Enclaves in Canada

Editor Roberto Perm York University Edition Coordinator Michel Guénette Library and Archives Canada Copyright by The Canadian Historical Association Ottawa, 2007 Published by the Canadian Historical Association with the support the Department of Canadian Heritage, Government of Canada ISBN 0-88798-266-2 Canada's Ethnic Groups ISSN 1483-9504 Canada's Ethnic Groups (print) ISSN 1715-8605 Canada's Ethnic Groups (Online) Jutekichi Miyagawa and his four children, Kazuko, Mitsuko, Michio and Yoshiko, in front of his grocery store, the Davie Confectionary, Vancouver, BC. March 1933 Library and Archives Canada I PA-103 544 Printed by Bonanza Printing & Copying Centre Inc. A HISTORY OF ETHNIC ENCLAVES IN CANADA John Zucchi All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, in any form or by any electronic or mechanical means including inlormation storage and retrieval systems, without permission in writing from the Canadian Historical Association. Ottawa, 2007 Canadian Historical Association Canada s Ethnic Group Series Booklet No. 31 A HISTORY OF ETHNIC ENCLAVES IN CANADA INTRODUCTION When we walk through Canadian cities nowadays, it is clear that ethnicity and multicul- turalism are alive and well in many neighbourhoods from coast to coast. One need only amble through the gates on Fisgard Street in Victoria or in Gastown in Vancouver to encounter vibrant Chinatowns, or through small roadways just off Dundas Street in Toronto to happen upon enclaves of Portuguese from the Azores; if you wander through the Côte- des-Neiges district in Montreal you will discover a polyethnic world - Kazakhis, Russian Jews, Vietnamese, Sri Lankans or Haitians among many other groups - while parts ot Dartmouth are home to an old African-Canadian community. -

Attachment No. 4

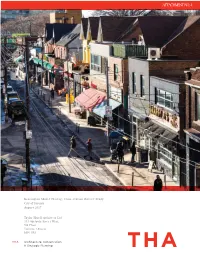

ATTACHMENT NO. 4 Kensington Market Heritage Conservation District Study City of Toronto August 2017 Taylor Hazell Architects Ltd. 333 Adelaide Street West, 5th Floor Toronto, Ontario M5V 1R5 Acknowledgements The study team gratefully acknowledges the efforts of the Stakeholder Advisory Committee for the Kensington Market HCD Study who provided thoughtful advice and direction throughout the course of the project. We would also like to thank Councillor Joe Cressy for his valuable input and support for the project during the stakeholder consultations and community meetings. COVER PHOTOGRAPH: VIEW WEST ALONG BALDWIN STREET (VIK PAHWA, 2016) KENSINGTON MARKET HCD STUDY | AUGUST 2017 TABLE OF CONTENTS PAGE XIII EXECUTIVE SUMMARY 3 1.0 INTRODUCTION 13 2.0 HISTORY & EVOLUTION 13 2.1 NATURAL LANDSCAPE 14 2.2 INDIGENOUS PRESENCE (1600-1700) 14 2.3 TORONTO’S PARK LOTS (1790-1850) 18 2.4 RESIDENTIAL DEVELOPMENT (1850-1900) 20 2.5 JEWISH MARKET (1900-1950) 25 2.6 URBAN RENEWAL ATTEMPTS (1950-1960) 26 2.7 CONTINUING IMMIGRATION (1950-PRESENT) 27 2.8 KENSINGTON COMMUNITY (1960-PRESENT) 33 3.0 ARCHAEOLOGICAL POTENTIAL 37 4.0 POLICY CONTEXT 37 4.1 PLANNING POLICY 53 4.2 HERITAGE POLICY 57 5.0 BUILT FORM & LANDSCAPE SURVEY 57 5.1 INTRODUCTION 57 5.2 METHODOLOGY 57 5.3 LIMITATIONS 61 6.0 COMMUNITY & STAKEHOLDER CONSULTATION 61 6.1 STAKEHOLDER CONSULTATION 63 6.2 COMMUNITY CONSULTATION 67 7.0 CHARACTER ANALYSIS 67 7.1 BLOCK & STREET PATTERNS i KENSINGTON MARKET HCD STUDY |AUGUST 2017 TABLE OF CONTENTS (CONTINUED) PAGE 71 7.2 PROPERTY FRONTAGES & PATTERNS -

Ten Neighbourhoods in Toronto with the Highest Total Crime Experience Vastly Different Crime Rates

Ten Neighbourhoods in Toronto with the Highest Total Crime Experience Vastly Different Crime Rates∗ Marginalized communnities experience different crime rates due to continued discrimination. Rachael Lam 29 January 2021 Abstract Neighbourhood Crime Rate data was pulled from the City of Toronto Open Portal to analyze neigh- bourhoods that were most affected by crime and how crime rates have changed over time. Although crime rates have risen between 2014-2019, certain neighbourhoods experience higher crime rates in the Greater Toronto Area. Further literature reviews of neighbourhoods who experience higher crime rates are also found to be economically disadvantaged communities. This data, without a further analysis and understanding of socioeconomic circumstances, could lead to higher police surveillance and further punitive action towards marginalized communities. Contents 1 Introduction 2 2 Data 2 3 Results 4 4 Discussion 4 4.1 Bay Street Corridor . .7 4.2 Moss Park . .7 4.3 Kensington-Chinatown . .7 4.4 Waterfront Communities-The Island . .7 4.5 Comparison . .7 5 Conclusion 8 References 9 ∗Code and data are available at: https://github.com/rachaellam/Toronto-Crime-Rates.git. 1 1 Introduction In 1971, Richard Nixon launched the War on Drugs followed by Ronald Reagan signing the Anti-Drug Abuse Act in 1986, initiating decades of increase police presence and highly punitive sentences. Public opinion shifted in support for harsher punishment leading to a massive increase in law-and-order government agencies (Marable 2015). Crime rate statistics were largely misconstrued to further push anti-crime policies that poorly affected low-income communities and communities of colour. These policies led to mass surveillance under the guise of safety and protection, continuing the cycle of oppression that marginalized communities face (Windsor, Dunlap, and Armour 2012). -

Active Transportation

Tuesday, September 10 & Wednesday, September 11 9:00 am – 12:00 pm WalkShops are fully included with registration, with no additional charges. Due to popular demand, we ask that attendees only sign-up for one cycling tour throughout the duration of the conference. Active Transportation Building Out a Downtown Bike Network Gain firsthand knowledge of Toronto's on-street cycling infrastructure while learning directly from people that helped implement it. Ride through downtown's unique neighborhoods with staff from the City's Cycling Infrastructure and Programs Unit as they lead a discussion of the challenges and opportunities the city faced when designing and building new biking infrastructure. The tour will take participants to multiple destinations downtown, including the Richmond and Adelaide Street cycle tracks, which have become the highest volume cycling facilities in Toronto since being originally installed as a pilot project in 2014. Lead: City of Toronto Transportation Services Mode: Cycling Accessibility: Moderate cycling, uneven surfaces This WalkShop is co-sponsored by WSP. If You Build (Parking) They Will Come: Bicycle Parking in Toronto Providing safe, accessible, and convenient bicycle parking is an essential part of any city's effort to support increased bicycle use. This tour will use Toronto's downtown core as a setting to explore best practices in bicycle parking design and management, while visiting several major destinations and cycling hotspots in the area. Starting at City Hall, we will visit secure indoor bicycle parking, on-street bike corrals, Union Station's off-street bike racks, the Bike Share Toronto system, and also provide a history of Toronto's iconic post and ring bike racks. -

Backgroundfile-156165.Pdf

REPORT FOR ACTION Appointments to Business Improvement Area Boards of Management Date: August 5, 2020 To: Toronto and East York Community Council From: General Manager, Economic Development and Culture Wards: 4, 10, 11, 12 and 14 SUMMARY The purpose of this report is to appoint directors to the Dupont by the Castle, Kensington Market and Pape Village BIA boards of management and remove directors from Baby Point Gates, Kensington Market, Pape Village and Trinity Bellwoods BIA boards of management. RECOMMENDATIONS The General Manager, Economic Development and Culture recommends that Toronto and East York Community Council: 1. In accordance with the City's Public Appointments Policy, appoint the following nominees to the Business Improvement Area (BIA) boards of management set out below at the pleasure of Toronto and East York Community Council, and for a term expiring at the end of the term of Council or as soon thereafter as successors are appointed: Dupont by the Castle: Chiu, Louis Star, Lisa Kensington Market: Krulicki, Jason Pape Village: Florence, Mark MacDonald, Susan BIA Board Appointments Page 1 of 3 2. Remove the following directors from the Business Improvement Area (BIA) boards of management set out below: Baby Point Gates: Healy, Jacob Kensington Market: Finkel, Julian Scriver, Felice Pape Village: McNeilly, Karen Noronha, Sophia Walsh, Julie Trinity Bellwoods: De Luca, Melissa FINANCIAL IMPACT There are no financial implications resulting from the adoption of this report. The Chief Financial Officer and Treasurer has reviewed this report and agrees with the financial impact information. DECISION HISTORY At its meeting of January 15, 2019, Toronto and East York Community Council appointed directors to Baby Point Gates, Dupont by the Castle, Kensington Market, Pape Village and Trinity Bellwoods BIA boards of management. -

Walking Tour: Downtown Toronto, Ontario

One of the best ways to experience a city is by Destinations Include: WALKING TOUR: walking around and exploring the different neigh- borhoods, cafes, and shops. This brochure serves as Cabbagetown DOWNTOWN a guide with many different interesting stops along Riverdale Farm TORONTO, ONTARIO the way, but you are encouraged to make your own Distillery District way throughout the city to find what interests you. It may seem that this tour involves excessive walk- St. Lawrence Market ing and distance, but with stops and sites along the Union Station way the time will fly by. Campbell House and Museum This tour was designed as a guideline for people in- terested in learning about the history and cultures of Spadina Chintown Toronto. Kensington Market By no means should you stick only to this as your Little Italy only guide! Take different streets, the subway, or a streetcar. Stop for lunch, coffee, or a beer. Royal Ontario Museum Knox College Above all: University of Toronto Ontario Legislative Building Enjoy yourself and all that Toronto has to offer!! Explore the history and Walking Tour designed and researched by: Kae Stringer various cultures of the world’s as part of the requirements for Advanced Projects in Public History most diverse city! for Dr. Doug Heffington, Summer 2011 A. Begin at Econo Lodge, 335 Jarvis Street: From the hotel, turn right I. Kensington Market is an artistic community with several mar- L. Knox College is a Presbyterian Seminary, and it is also a part of and walk through the Allen Gardens Park on the right to Carlton Street . -

Yiddish Theatre Meets Kung Fu Film in Artist Shellie Zhang's New Neon

FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE Yiddish theatre meets Kung Fu film in artist Shellie Zhang’s new neon light installation at the FENTSTER Gallery on College Street Chinese-Canadian artist Shellie Zhang explores how Toronto’s Jewish and Chinese communities fostered their cultural identities on the same site—a theatre at the corner of Spadina and Dundas built in 1921 as a showcase for Yiddish theatre. Toronto, ON, February 28, 2018 – In a striking new neon light installation for the FENTSTER window gallery, Toronto-based and Beijing-born multidisciplinary artist Shellie Zhang reimagines marquee signage representing two significant cultural institutions established by Chinese and Jewish newcomers to Toronto. Running from February 26 to May 22, 2018, A Place for Wholesome Amusement opens with a free event on Thursday, March 15 from 7 to 9 PM. FENTSTER is located in the storefront window of the Jewish community, Makom: Creative Downtown Judaism, 402 College Street, Toronto. The exhibition is curated by Donna Bernardo-Ceriz, Dara Solomon and Evelyn Tauben. To create this site-specific exhibition, Zhang was invited to mine the extensive holdings of the UJA Federation’s Ontario Jewish Archives, Blankenstein Family Heritage Centre (OJA) for intersections between Chinese and Jewish histories in Toronto. Her research led to the building on the north-east corner of Dundas and Spadina, the Standard Theatre, the first purpose-built Yiddish theatre in Canada. Five decades later, the theatre hosted the Golden Harvest Theatre, a cinema featuring Hong Kong films – primarily kung fu, action thrillers, and comedies. About this site, Zhang said, “There is something very special about the fact that this building was home to two different spaces that offered cultural and language connections for those who sought it. -

25-Storeys By-The-Lake Community Connections

TORONTO EDITION FRIDAY, FEBRUARY 20, 2015 Vol. 19 • No. 8 Mimico plan challenged Discussions on open data 25-STOREYS COMMUNITY BY-THE-LAKE CONNECTIONS By Edward LaRusic By Leah Wong With the fi rst development proposal within the secondary plan Toronto’s open data community wants local leaders to rely area not refl ecting the Mimico-by-the-Lake vision, residents less on anecdotal evidence and more on facts when it to fear the secondary plan will be signifi cantly revised before it is comes to policy decisions. even implemented. Th is weekend open data enthusiasts, government offi cials Shoreline Towers Inc. proposes to construct a 25-storey and community organizers will come together for the building on an existing parking lot at 2313 and 2323 Lake city’s Open Data Day activities to discuss how to use data Shore Boulevard West. Th e site is east of two existing 10-storey to improve the city. Among the topics being tackled this apartment buildings that front on Lake Shore Boulevard West, weekend is how to incorporate data into neighbourhood also owned by Shoreline. revitalization policies. Mimico Lakeshore Network co-chair Martin Gerwin “Th e wonderful thing about open data in policy making told NRU that part of the issue is that this parking lot was is that it’s fact-based. Many politicians will make a lot of calls never considered for redevelopment of this nature when the based on anecdotes or platforms,” one of the organizers and secondary plan was approved. Th e plan, which is currently CitizenBridge founding member Richard Pietro told NRU.