PRDM1 Controls the Sequential Activation of Neural, Neural Crest and Sensory

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Activated Peripheral-Blood-Derived Mononuclear Cells

Transcription factor expression in lipopolysaccharide- activated peripheral-blood-derived mononuclear cells Jared C. Roach*†, Kelly D. Smith*‡, Katie L. Strobe*, Stephanie M. Nissen*, Christian D. Haudenschild§, Daixing Zhou§, Thomas J. Vasicek¶, G. A. Heldʈ, Gustavo A. Stolovitzkyʈ, Leroy E. Hood*†, and Alan Aderem* *Institute for Systems Biology, 1441 North 34th Street, Seattle, WA 98103; ‡Department of Pathology, University of Washington, Seattle, WA 98195; §Illumina, 25861 Industrial Boulevard, Hayward, CA 94545; ¶Medtronic, 710 Medtronic Parkway, Minneapolis, MN 55432; and ʈIBM Computational Biology Center, P.O. Box 218, Yorktown Heights, NY 10598 Contributed by Leroy E. Hood, August 21, 2007 (sent for review January 7, 2007) Transcription factors play a key role in integrating and modulating system. In this model system, we activated peripheral-blood-derived biological information. In this study, we comprehensively measured mononuclear cells, which can be loosely termed ‘‘macrophages,’’ the changing abundances of mRNAs over a time course of activation with lipopolysaccharide (LPS). We focused on the precise mea- of human peripheral-blood-derived mononuclear cells (‘‘macro- surement of mRNA concentrations. There is currently no high- phages’’) with lipopolysaccharide. Global and dynamic analysis of throughput technology that can precisely and sensitively measure all transcription factors in response to a physiological stimulus has yet to mRNAs in a system, although such technologies are likely to be be achieved in a human system, and our efforts significantly available in the near future. To demonstrate the potential utility of advanced this goal. We used multiple global high-throughput tech- such technologies, and to motivate their development and encour- nologies for measuring mRNA levels, including massively parallel age their use, we produced data from a combination of two distinct signature sequencing and GeneChip microarrays. -

A PAX5-OCT4-PRDM1 Developmental Switch Specifies Human Primordial Germ Cells

A PAX5-OCT4-PRDM1 Developmental Switch Specifies Human Primordial Germ Cells Fang Fang1,2, Benjamin Angulo1,2, Ninuo Xia1,2, Meena Sukhwani3, Zhengyuan Wang4, Charles C Carey5, Aurélien Mazurie5, Jun Cui1,2, Royce Wilkinson5, Blake Wiedenheft5, Naoko Irie6, M. Azim Surani6, Kyle E Orwig3, Renee A Reijo Pera1,2 1Department of Cell Biology and Neurosciences, Montana State University, Bozeman, MT 59717, USA 2Department of Chemistry and Biochemistry, Montana State University, Bozeman, MT 59717, USA 3Department of Obstetrics, Gynecology and Reproductive Sciences, University of Pittsburgh, School of Medicine; Magee Women’s Research Institute, Pittsburgh, PA, 15213, USA 4Genomic Medicine Division, Hematology Branch, NHLBI/NIH, MD 20850, USA 5Department of Microbiology and Immunology, Montana State University, Bozeman, MT 59717, USA. 6Wellcome Trust Cancer Research UK Gurdon Institute, Tennis Court Road, University of Cambridge, Cambridge CB2 1QN, UK. Correspondence should be addressed to F.F. (e-mail: [email protected]) 1 Abstract Dysregulation of genetic pathways during human germ cell development leads to infertility. Here, we analyzed bona fide human primordial germ cells (hPGCs) to probe the developmental genetics of human germ cell specification and differentiation. We examined distribution of OCT4 occupancy in hPGCs relative to human embryonic stem cells (hESCs). We demonstrate that development, from pluripotent stem cells to germ cells, is driven by switching partners with OCT4 from SOX2 to PAX5 and PRDM1. Gain- and loss-of-function studies revealed that PAX5 encodes a critical regulator of hPGC development. Moreover, analysis of epistasis indicates that PAX5 acts upstream of OCT4 and PRDM1. The PAX5-OCT4-PRDM1 proteins form a core transcriptional network that activates germline and represses somatic programs during human germ cell differentiation. -

![Viewed in [2, 3])](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/8069/viewed-in-2-3-428069.webp)

Viewed in [2, 3])

Yildiz et al. Neural Development (2019) 14:5 https://doi.org/10.1186/s13064-019-0129-x RESEARCH ARTICLE Open Access Zebrafish prdm12b acts independently of nkx6.1 repression to promote eng1b expression in the neural tube p1 domain Ozge Yildiz1, Gerald B. Downes2 and Charles G. Sagerström1* Abstract Background: Functioning of the adult nervous system depends on the establishment of neural circuits during embryogenesis. In vertebrates, neurons that make up motor circuits form in distinct domains along the dorsoventral axis of the neural tube. Each domain is characterized by a unique combination of transcription factors (TFs) that promote a specific fate, while repressing fates of adjacent domains. The prdm12 TF is required for the expression of eng1b and the generation of V1 interneurons in the p1 domain, but the details of its function remain unclear. Methods: We used CRISPR/Cas9 to generate the first germline mutants for prdm12 and employed this resource, together with classical luciferase reporter assays and co-immunoprecipitation experiments, to study prdm12b function in zebrafish. We also generated germline mutants for bhlhe22 and nkx6.1 to examine how these TFs act with prdm12b to control p1 formation. Results: We find that prdm12b mutants lack eng1b expression in the p1 domain and also possess an abnormal touch-evoked escape response. Using luciferase reporter assays, we demonstrate that Prdm12b acts as a transcriptional repressor. We also show that the Bhlhe22 TF binds via the Prdm12b zinc finger domain to form a complex. However, bhlhe22 mutants display normal eng1b expression in the p1 domain. While prdm12 has been proposed to promote p1 fates by repressing expression of the nkx6.1 TF, we do not observe an expansion of the nkx6.1 domain upon loss of prdm12b function, nor is eng1b expression restored upon simultaneous loss of prdm12b and nkx6.1. -

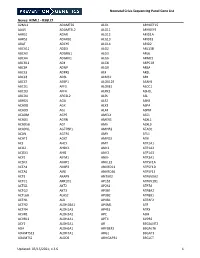

NICU Gene List Generator.Xlsx

Neonatal Crisis Sequencing Panel Gene List Genes: A2ML1 - B3GLCT A2ML1 ADAMTS9 ALG1 ARHGEF15 AAAS ADAMTSL2 ALG11 ARHGEF9 AARS1 ADAR ALG12 ARID1A AARS2 ADARB1 ALG13 ARID1B ABAT ADCY6 ALG14 ARID2 ABCA12 ADD3 ALG2 ARL13B ABCA3 ADGRG1 ALG3 ARL6 ABCA4 ADGRV1 ALG6 ARMC9 ABCB11 ADK ALG8 ARPC1B ABCB4 ADNP ALG9 ARSA ABCC6 ADPRS ALK ARSL ABCC8 ADSL ALMS1 ARX ABCC9 AEBP1 ALOX12B ASAH1 ABCD1 AFF3 ALOXE3 ASCC1 ABCD3 AFF4 ALPK3 ASH1L ABCD4 AFG3L2 ALPL ASL ABHD5 AGA ALS2 ASNS ACAD8 AGK ALX3 ASPA ACAD9 AGL ALX4 ASPM ACADM AGPS AMELX ASS1 ACADS AGRN AMER1 ASXL1 ACADSB AGT AMH ASXL3 ACADVL AGTPBP1 AMHR2 ATAD1 ACAN AGTR1 AMN ATL1 ACAT1 AGXT AMPD2 ATM ACE AHCY AMT ATP1A1 ACO2 AHDC1 ANK1 ATP1A2 ACOX1 AHI1 ANK2 ATP1A3 ACP5 AIFM1 ANKH ATP2A1 ACSF3 AIMP1 ANKLE2 ATP5F1A ACTA1 AIMP2 ANKRD11 ATP5F1D ACTA2 AIRE ANKRD26 ATP5F1E ACTB AKAP9 ANTXR2 ATP6V0A2 ACTC1 AKR1D1 AP1S2 ATP6V1B1 ACTG1 AKT2 AP2S1 ATP7A ACTG2 AKT3 AP3B1 ATP8A2 ACTL6B ALAS2 AP3B2 ATP8B1 ACTN1 ALB AP4B1 ATPAF2 ACTN2 ALDH18A1 AP4M1 ATR ACTN4 ALDH1A3 AP4S1 ATRX ACVR1 ALDH3A2 APC AUH ACVRL1 ALDH4A1 APTX AVPR2 ACY1 ALDH5A1 AR B3GALNT2 ADA ALDH6A1 ARFGEF2 B3GALT6 ADAMTS13 ALDH7A1 ARG1 B3GAT3 ADAMTS2 ALDOB ARHGAP31 B3GLCT Updated: 03/15/2021; v.3.6 1 Neonatal Crisis Sequencing Panel Gene List Genes: B4GALT1 - COL11A2 B4GALT1 C1QBP CD3G CHKB B4GALT7 C3 CD40LG CHMP1A B4GAT1 CA2 CD59 CHRNA1 B9D1 CA5A CD70 CHRNB1 B9D2 CACNA1A CD96 CHRND BAAT CACNA1C CDAN1 CHRNE BBIP1 CACNA1D CDC42 CHRNG BBS1 CACNA1E CDH1 CHST14 BBS10 CACNA1F CDH2 CHST3 BBS12 CACNA1G CDK10 CHUK BBS2 CACNA2D2 CDK13 CILK1 BBS4 CACNB2 CDK5RAP2 -

Recombinant PRDM1 Protein

Recombinant PRDM1 protein Catalog No: 81277, 81977 Quantity: 20, 1000 µg Expressed In: Baculovirus Concentration: 0.4 µg/µl Source: Human Buffer Contents: Recombinant PRDM1 protein is supplied in 25 mM HEPES-NaOH pH 7.5, 300 mM NaCl, 10% glycerol, 0.04% Triton X-100, 0.5 mM TCEP. Background: PRDM1 (PR/SET Domain 1), also called as Beta-Interferon Gene Positive-Regulatory Domain I Binding Factor, or BLIMP1, is a transcription factor that acts as a repressor of beta-interferon gene expression. It mediates a transcriptional program in various innate and adaptive immune tissue-resident lymphocyte T cell types such as tissue resident memory T (Trm), natural killer (trNK) and natural killer T (NKT) cells and negatively regulates gene expression of proteins that promote the egress of tissue-resident T-cell populations from non-lymphoid organs. PRDM1 plays a role in the development, retention and long-term establishment of adaptive and innate tissue- resident lymphocyte T cell types in non-lymphoid organs, such as the skin and gut, but also in other nonbarrier tissues like liver and kidney, and therefore may provide immediate immunological protection against reactivating infections or viral reinfection (By similarity). Protein Details: Recombinant PRDM1 was expressed in a baculovirus expression system as the full length protein (accession number NP_001189.2) with an N-terminal FLAG tag. The molecular weight of PRDM1 is 93 kDa. Application Notes: This product was manufactured as described in Protein Details. Recombinant PRDM1 protein gel Where possible, Active Motif has developed functional or activity assays for 9% SDS-PAGE gel with Coomassie recombinant proteins. -

GATA2 Regulates Mast Cell Identity and Responsiveness to Antigenic Stimulation by Promoting Chromatin Remodeling at Super- Enhancers

ARTICLE https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-020-20766-0 OPEN GATA2 regulates mast cell identity and responsiveness to antigenic stimulation by promoting chromatin remodeling at super- enhancers Yapeng Li1, Junfeng Gao 1, Mohammad Kamran1, Laura Harmacek2, Thomas Danhorn 2, Sonia M. Leach1,2, ✉ Brian P. O’Connor2, James R. Hagman 1,3 & Hua Huang 1,3 1234567890():,; Mast cells are critical effectors of allergic inflammation and protection against parasitic infections. We previously demonstrated that transcription factors GATA2 and MITF are the mast cell lineage-determining factors. However, it is unclear whether these lineage- determining factors regulate chromatin accessibility at mast cell enhancer regions. In this study, we demonstrate that GATA2 promotes chromatin accessibility at the super-enhancers of mast cell identity genes and primes both typical and super-enhancers at genes that respond to antigenic stimulation. We find that the number and densities of GATA2- but not MITF-bound sites at the super-enhancers are several folds higher than that at the typical enhancers. Our studies reveal that GATA2 promotes robust gene transcription to maintain mast cell identity and respond to antigenic stimulation by binding to super-enhancer regions with dense GATA2 binding sites available at key mast cell genes. 1 Department of Immunology and Genomic Medicine, National Jewish Health, Denver, CO 80206, USA. 2 Center for Genes, Environment and Health, National Jewish Health, Denver, CO 80206, USA. 3 Department of Immunology and Microbiology, University of Colorado Anschutz Medical Campus, Aurora, ✉ CO 80045, USA. email: [email protected] NATURE COMMUNICATIONS | (2021) 12:494 | https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-020-20766-0 | www.nature.com/naturecommunications 1 ARTICLE NATURE COMMUNICATIONS | https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-020-20766-0 ast cells (MCs) are critical effectors in immunity that at key MC genes. -

Developmental Biology 399 (2015) 164–176

Developmental Biology 399 (2015) 164–176 Contents lists available at ScienceDirect Developmental Biology journal homepage: www.elsevier.com/locate/developmentalbiology The requirement of histone modification by PRDM12 and Kdm4a for the development of pre-placodal ectoderm and neural crest in Xenopus Shinya Matsukawa a, Kyoko Miwata b, Makoto Asashima b, Tatsuo Michiue a,n a Department of Sciences (Biology), Graduate School of Arts and Sciences, University of Tokyo, 3-8-1 Komaba, Meguro-ku, Tokyo 153-8902, Japan b Research Center for Stem Cell Engineering National Institute of Advanced Industrial Science and Technology (AIST), Tsukuba City, Ibaraki, Japan article info abstract Article history: In vertebrates, pre-placodal ectoderm and neural crest development requires morphogen gradients and Received 6 September 2014 several transcriptional factors, while the involvement of histone modification remains unclear. Here, we Received in revised form report that histone-modifying factors play crucial roles in the development of pre-placodal ectoderm 21 November 2014 and neural crest in Xenopus. During the early neurula stage, PRDM12 was expressed in the lateral pre- Accepted 23 December 2014 placodal ectoderm and repressed the expression of neural crest specifier genes via methylation of Available online 6 January 2015 histone H3K9. ChIP-qPCR analyses indicated that PRDM12 promoted the occupancy of the trimethylated Keywords: histone H3K9 (H3K9me3) on the Foxd3, Slug, and Sox8 promoters. Injection of the PRDM12 MO inhibited fi Histone modi cation the expression of presumptive trigeminal placode markers and decreased the occupancy of H3K9me3 on PRDM12 the Foxd3 promoter. Histone demethylase Kdm4a also inhibited the expression of presumptive Kdm4a trigeminal placode markers in a similar manner to PRDM12 MO and could compensate for the effects Pre-placodal ectoderm Neural crest of PRDM12. -

Pan-HDAC Inhibitors Restore PRDM1 Response to IL21 in CREBBP

Published OnlineFirst October 22, 2018; DOI: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-18-1153 Cancer Therapy: Preclinical Clinical Cancer Research Pan-HDAC Inhibitors Restore PRDM1 Response to IL21 in CREBBP-Mutated Follicular Lymphoma Fabienne Desmots1,2, Mikael€ Roussel1,2,Celine Pangault1,2, Francisco Llamas-Gutierrez3,Cedric Pastoret1,2, Eric Guiheneuf2,Jer ome^ Le Priol2, Valerie Camara-Clayette4, Gersende Caron1,2, Catherine Henry5, Marc-Antoine Belaud-Rotureau5, Pascal Godmer6, Thierry Lamy1,7, Fabrice Jardin8, Karin Tarte1,9, Vincent Ribrag4, and Thierry Fest1,2 Abstract Purpose: Follicular lymphoma arises from a germinal cen- is enriched in the potent inducer of PRDM1 and IL21, highly ter B-cell proliferation supported by a bidirectional crosstalk produced by Tfhs. In follicular lymphoma carrying CREBBP with tumor microenvironment, in particular with follicular loss-of-function mutations, we found a lack of IL21-mediated helper T cells (Tfh). We explored the relation that exists PRDM1 response associated with an abnormal increased between the differentiation arrest of follicular lymphoma cells enrichment of the BCL6 protein repressor in PRDM1 gene. and loss-of-function of CREBBP acetyltransferase. Moreover, in these follicular lymphoma cells, pan-HDAC Experimental Design: The study used human primary cells inhibitor, vorinostat, restored their PRDM1 response to IL21 obtained from either follicular lymphoma tumors character- by lowering BCL6 bound to PRDM1. This finding was rein- ized for somatic mutations, or inflamed tonsils for normal forced by our exploration of patients with follicular lympho- germinal center B cells. Transcriptome and functional analyses ma treated with another pan-HDAC inhibitor. Patients were done to decipher the B- and T-cell crosstalk. -

In Vitro Differentiation of Human Skin-Derived Cells Into Functional

cells Article In Vitro Differentiation of Human Skin-Derived Cells into Functional Sensory Neurons-Like Adeline Bataille 1 , Raphael Leschiera 1, Killian L’Hérondelle 1, Jean-Pierre Pennec 2, Nelig Le Goux 3, Olivier Mignen 3, Mehdi Sakka 1, Emmanuelle Plée-Gautier 1,4 , Cecilia Brun 5 , Thierry Oddos 5, Jean-Luc Carré 1,4, Laurent Misery 1,6 and Nicolas Lebonvallet 1,* 1 EA4685 Laboratory of Interactions Neurons-Keratinocytes, Faculty of Medicine and Health Sciences, University of Western Brittany, F-29200 Brest, France; [email protected] (A.B.); [email protected] (R.L.); [email protected] (K.L.); [email protected] (M.S.); [email protected] (E.P.-G.); [email protected] (J.-L.C.); [email protected] (L.M.) 2 EA 4324 Optimization of Physiological Regulation, Faculty of Medicine and Health Sciences, University of Western Brittany, F-29200 Brest, France; [email protected] 3 INSERM UMR1227 B Lymphocytes and autoimmunity, University of Western Brittany, F-29200 Brest, France; [email protected] (N.L.G.); [email protected] (O.M.) 4 Department of Biochemistry and Pharmaco-Toxicology, University Hospital of Brest, 29609 Brest, France 5 Johnson & Johnson Santé Beauté France Upstream Innovation, F-27100 Val de Reuil, France; [email protected] (C.B.); [email protected] (T.O.) 6 Department of Dermatology, University Hospital of Brest, 29609 Brest, France * Correspondence: [email protected]; Tel.: +33-2-98-01-21-81 Received: 23 March 2020; Accepted: 14 April 2020; Published: 17 April 2020 Abstract: Skin-derived precursor cells (SKPs) are neural crest stem cells that persist in certain adult tissues, particularly in the skin. -

Transcriptional Regulator PRDM12 Is Essential for Human Pain

LETTERS Transcriptional regulator PRDM12 is essential for human pain perception Ya-Chun Chen1,2,52, Michaela Auer-Grumbach3,52, Shinya Matsukawa4, Manuela Zitzelsberger5, Andreas C Themistocleous6,7, Tim M Strom8,9, Chrysanthi Samara10, Adrian W Moore11, Lily Ting-Yin Cho12, Gareth T Young12, Caecilia Weiss5, Maria Schabhüttl3, Rolf Stucka5, Annina B Schmid6,13, Yesim Parman14, Luitgard Graul-Neumann15, Wolfram Heinritz16,17, Eberhard Passarge17,18, Rosemarie M Watson19, Jens Michael Hertz20, Ute Moog21, Manuela Baumgartner22, Enza Maria Valente23, Diego Pereira24, Carlos M Restrepo25, Istvan Katona26, Marina Dusl5, Claudia Stendel5,27, Thomas Wieland8, Fay Stafford1,2, Frank Reimann28, Katja von Au29, Christian Finke30, Patrick J Willems31, Michael S Nahorski1,2, Samiha S Shaikh1,2, Ofélia P Carvalho1,2, Adeline K Nicholas2, Gulshan Karbani32, Maeve A McAleer19, Maria Roberta Cilio33,34, John C McHugh35, Sinead M Murphy36,37, Alan D Irvine19,38, Uffe Birk Jensen39, Reinhard Windhager3, Joachim Weis26, Carsten Bergmann40–42, Bernd Rautenstrauss5,43, Jonathan Baets44–46, Peter De Jonghe44–46, Mary M Reilly47, Regina Kropatsch48, Ingo Kurth49, Roman Chrast9,50,51, Tatsuo Michiue4, David L H Bennett6, C Geoffrey Woods1,2 & Jan Senderek5 Pain perception has evolved as a warning mechanism to alert exome sequencing on the index patient of family A and the unre- organisms to tissue damage and dangerous environments1,2. lated single CIP patient from family B. Although exome sequenc- In humans, however, undesirable, excessive or chronic pain ing of the subject from family A yielded no obvious pathogenic is a common and major societal burden for which available variant in genes located in the autozygous region on chromosome 9, medical treatments are currently suboptimal3,4. -

Plasmablastic Lymphoma Phenotype Is Determined by Genetic Alterations

Modern Pathology (2017) 30, 85–94 © 2017 USCAP, Inc All rights reserved 0893-3952/17 $32.00 85 Plasmablastic lymphoma phenotype is determined by genetic alterations in MYC and PRDM1 Santiago Montes-Moreno1,2, Nerea Martinez-Magunacelaya2, Tomás Zecchini-Barrese1, Sonia Gonzalez de Villambrosía3, Emma Linares1, Tamara Ranchal4, María Rodriguez-Pinilla4, Ana Batlle3, Laura Cereceda-Company2, Jose Bernardo Revert-Arce5, Carmen Almaraz2 and Miguel A Piris1,2 1Pathology Department, Servicio de Anatomía Patológica, Hospital Universitario Marqués de Valdecilla/ IDIVAL, Santander, Spain; 2Laboratorio de Genómica del Cáncer, IDIVAL, Santander, Spain; 3Hematology Department, Cytogenetics Unit, Hospital Universitario Marqués de Valdecilla/IDIVAL, Santander, Spain; 4Pathology Department, Fundación Jiménez Díaz, Madrid, Spain and 5Valdecilla Tumor Biobank Unit, HUMV/IDIVAL, Santander, Spain Plasmablastic lymphoma is an uncommon aggressive non-Hodgkin B-cell lymphoma type defined as a high- grade large B-cell neoplasm with plasma cell phenotype. Genetic alterations in MYC have been found in a proportion (~60%) of plasmablastic lymphoma cases and lead to MYC-protein overexpression. Here, we performed a genetic and expression profile of 36 plasmablastic lymphoma cases and demonstrate that MYC overexpression is not restricted to MYC-translocated (46%) or MYC-amplified cases (11%). Furthermore, we demonstrate that recurrent somatic mutations in PRDM1 are found in 50% of plasmablastic lymphoma cases (8 of 16 cases evaluated). These mutations target critical functional domains (PR motif, proline rich domain, acidic region, and DNA-binding Zn-finger domain) involved in the regulation of different targets such as MYC. Furthermore, these mutations are found frequently in association with MYC translocations (5 out of 9, 56% of cases with MYC translocations were PRDM1-mutated), but not restricted to those cases, and lead to expression of an impaired PRDM1/Blimp1α protein. -

Chronological Gene Expression of Human Gingival Fibroblasts with Low Reactive Level Laser (LLL) Irradiation

Journal of Clinical Medicine Article Chronological Gene Expression of Human Gingival Fibroblasts with Low Reactive Level Laser (LLL) Irradiation Yuki Wada 1 , Asami Suzuki 2,*, Hitomi Ishiguro 1,3, Etsuko Murakashi 1 and Yukihiro Numabe 1,3 1 Department of Periodontology, School of Life Dentistry at Tokyo, The Nippon Dental University, 1-9-20 Fujimi, Chiyoda-ku, Tokyo 102-8159, Japan; [email protected] (Y.W.); [email protected] (H.I.); [email protected] (E.M.); [email protected] (Y.N.) 2 Division of General Dentistry, The Nippon Dental University Hospital, 2-3-16 Fujimi, Chiyoda-ku, Tokyo 102-8158, Japan 3 Dental Education Support Center, School of Life Dentistry, The Nippon Dental University, 1-9-20 Fujimi, Chiyoda-ku, Tokyo 102-8159, Japan * Correspondence: [email protected]; Tel.: +81-3-3261-5511 Abstract: Though previously studies have reported that Low reactive Level Laser Therapy (LLLT) promotes wound healing, molecular level evidence was uncleared. The purpose of this study is to examine the temporal molecular processes of human immortalized gingival fibroblasts (HGF) by LLLT by the comprehensive analysis of gene expression. HGF was seeded, cultured for 24 h, and then irradiated with a Nd: YAG laser at 0.5 W for 30 s. After that, gene differential expression analysis and functional analysis were performed with DNA microarray at 1, 3, 6 and 12 h after the irradiation. The number of genes with up- and downregulated differentially expression genes (DEGs) compared to the nonirradiated group was large at 6 and 12 h after the irradiation.