An Analytic Review of the 10-Year Good Neighborhoods Initiative

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Adopted Grosse Pointe Estate Historic District Preliminary Study

PRELIMINARY HISTORIC DISTRICT STUDY COMMITTEE REPORT GROSSE POINTE ESTATE HISTORIC DISTRICT GROSSE POINTE, MICHIGAN Adopted FEBRUARY 15, 2021 CHARGE OF THE HISTORIC DISTRICT STUDY COMMITTEE The historic district study committee was appointed by the Grosse Pointe City Council on December 14, 2020, pursuant to PA 169 of 1970 as amended. The study committee was charged with conducting an inventory, research, and preparation of a preliminary historic district study committee report for the following areas of the city: o Lakeland Ave from Maumee to Lake St. Clair o University Place from Maumee to Jefferson o Washington Road from Maumee to Jefferson o Lincoln Road from Maumee to Jefferson o Entirety of Rathbone Place o Entirety of Woodland Place o The lakefront homes and property immediately adjacent to the lakefront homes on Donovan Place, Wellington Place, Stratford Place, and Elmsleigh Place Upon completion of the report the study committee is charged with holding a public hearing and making a recommendation to city council as to whether a historic district ordinance should be adopted, and a local historic district designated. A list of study committee members and their qualifications follows. STUDY COMMITTEE MEMBERS George Bailey represents the Grosse Pointe Historical Society on the committee. He is an architect and has projects in historic districts in Detroit; Columbus, OH; and Savannah, GA. He is a history aficionado and serves on the Grosse Pointe Woods Historic Commission and Planning Commission. Kay Burt-Willson is the secretary of the Rivard Park Home Owners Association and the Vice President of Education for the Grosse Pointe Historical Society. -

Shrine of the Black Madonna

NPS Form 10-900 OMB No. 1024-0018 United States Department of the Interior National Park Service National Register of Historic Places Registration Form This form is for use in nominating or requesting determinations for individual properties and districts. See instructions in National Register Bulletin, How to Complete the National Register of Historic Places Registration Form. If any item does not apply to the property being documented, enter "N/A" for "not applicable." For functions, architectural classification, materials, and areas of significance, enter only categories and subcategories from the instructions. 1. Name of Property Historic name: Shrine of the Black Madonna of the Pan African Orthodox Christian Church Other names/site number: Pilgrim Congregational Church, Brewster-Pilgrim Congregational Church, Central Congregational Church Name of related multiple property listing: The Civil Rights Movement and the African American Experience in 20th Century Detroit (Enter "N/A" if property is not part of a multiple property listing ____________________________________________________________________________ 2. Location Street & number: 7625 Linwood Street City or town: Detroit State: Michigan County: Wayne Not For Publication: Vicinity: _____________________________ _______________________________________________ 3. State/Federal Agency Certification As the designated authority under the National Historic Preservation Act, as amended, I hereby certify that this X nomination ___ request for determination of eligibility meets the documentation -

C:\Documents and Settings\Boscarinot.DETROIT

Final Report Proposed Broadway Avenue Local Historic District By a resolution dated January 26, 2005, the Detroit City Council charged the Historic Designation Advisory Board, a study committee, with the official study of the proposed Broadway Avenue Local Historic District in accordance with Chapter 25 of the 1984 Detroit City Code and the Michigan Local Historic Districts Act. The proposed Broadway Avenue Local Historic District is composed of fifteen buildings (fourteen contributing, one non-contributing) located on parts of two noncontiguous blocks in downtown Detroit between Grand Circus Park (Witherell) and Gratiot Avenue. These commercial buildings range in date of construction from c. 1896-97 to 1926 and in height from two to fourteen stories. The northernmost noncontiguous portion in the 1500 block of Broadway is located in the National- Register-listed Grand Circus Park Historic District; and the southern noncontiguous portion in the 1300 block, is identical to the Broadway Avenue Historic District (NR 2004). Boundaries: The boundaries of the proposed Broadway Avenue Local Historic District are outlined in heavy black on the attached map, and are as follows: Southern noncontiguous portion: Beginning at a point, that point being the intersection of the centerline of East Grand River Avenue with the centerline of the alley parallel to and between Broadway Avenue and Center Street; thence southeast along the centerline of said alley to its intersection with the northwest line of Lot 5, Plat of Section 9, Governor & Judges Plan, -

Singer Talks Sexuality, Gay Icons and New Youtube Doc

FALL HOME GUIDE 4 Las Vegas Shooting Surpasses Orlando as Deadliest in U.S. History LGBT Middle-Eastern Americans Find Community During Arabian Nights Guidance: Not Infectious, HIV Science Turns a Corner DEMIDEMI LOVATOLOVATO ONON HERHER OWNOWN TERMSTERMS ‘Sorry Not Sorry’ Singer Talks Sexuality, Gay Icons and New YouTube Doc WWW.PRIDESOURCE.COM October is LGBTQ History Month OCTOBER 5, 2017 | VOL. 2540 | FREE FEATURE OCTOBER LGBTQ HISTORY MONTH COVER 26 Demi Lovato On Her Own Terms NEWS 10 Coming Out in the Middle Eastern Community 4 Las Vegas Shooting Surpasses Orlando as Deadliest in U.S. History LGBTQ HISTORY MONTH 4 Court Upholds Ruling for Miss. Anti-LGBT Law - But 16 Charles Alexander’s ‘Art and There’s Stinging Dissent Autograph’ Debuts, Exhibit and 14 Stonewall Strong 5 GNA Funding Gender Marker Changes on Passport Plus 4 Online Only Features Cards Book Signing Oct. 6 9 SCOTUS Denies Review of Appeals Court Decision Striking Down Sex Offender Law 9 White House Distances Trump from Roy Moore’s Anti-Gay Views THEATER BTL FALL HOME GUIDE 9 LGBT Groups Cheer Price’s Resignation as Health Secretary 11 Guidance: Not Infectious, HIV Science Turns a Corner OPINION 10 Parting Glances 11 Viewpoint: Ann Arbor Purge, Tim Retzloff 11 Creep of the Week: Jeff Mateer LIFE 28 Happenings 31 Screen Queen 29 Ringwald Does ‘The Time Warp Now’ 33 Puzzle and Comic with Rocky Horror 34 Classifieds HOME 35 Deep Inside Hollywood 17 Approachable and Comfortable Design 30 Dark Tale of ‘Sweeney Todd’ Finds COMMUNITY CONNECTIONS 18 Tips for Buyers and Sellers in Our ‘Hot’ Housing Market 36 Fall Fling Marks 10 Year Anniversary of Second Life at The Encore 20 Marriage Equality Paving the Way for Increased LGBTQ Affirmations Building Interest in Home Ownership 36 Fair Michigan Gets Justice for Gay Man VOL. -

March 2014 Make Your Next Simcha EPIC WEDDING MITZVAH BIRTHDAY SHOWER GRADUATION RETIREMENT OFF-SITE SIMCHAHS CHARITY CORPORATE TRAY CATERING

A Jewish Renaissance Media Publication ENCHANTED PHOTOGRAPHY BY MARLA MICHELE MUST march 2014 Make Your Next Simcha EPIC WEDDING MITZVAH BIRTHDAY SHOWER GRADUATION RETIREMENT OFF-SITE SIMCHAHS CHARITY CORPORATE TRAY CATERING 313.567.2622 248.646.7900 248.305.5210 248.432.5654 Troy: 248.646.7923 248.356.2310 Southfi eld: 248.864.4410 Toll Free 855.543.EPIC | theepicureangroup.com Create an unforgettable Simcha -minus the stress Elegant to Casual Exceeding your expectation at every step Bar / Bat Mitzvahs at their Best Cuisine from simple to gourmet 2 Vaad certified providers available From fun facilitators, designer center pieces, DJ’s, videography – we do it all Orthodox to Reform Experienced, knowledgeable, ready to serve Exclusive access to 10 acres of unparalleled fun! Formula Go Karts 2 Kiddie Go Kart Track 2 Laser Tag Mini-Bowling 2 Trampoline Center 2 Miniature Golf Climbing Walls 2 Automatic Soccer Cages Event Rooms 2 Incredible Arcade 2 4 Acres of Picnic Area 4EVEHMWI4EVO Restaurant 2 An impeccably clean, first class facility www.paradiseparknovi.com 248.735.1050 Grand River in Novi march 2014 Set the Stage for a Memorable Wedding at the Historic Detroit Opera House Right: Sam and Jennie (Beitner) Maxbauer of Royal Oak at their wedding at Congregation Shaarey Zedek in Southfield on Oct. 27, 2013. Cover photo: Kailey Egrin of Huntington Woods kisses her 106-year-old great- grandma Sonia Glaser at her bat mitzvah in December. LIEBERMAN PHOTOGRAPHY contents C6 All Dressed Up Trendy styles for the bat mitzvah girl and her mom. C10 Picture Perfect The latest trends in makeup for brides-to-be. -

1964 So Much Older Then

SO MUCH OLDER THEN BOB DYLAN 1964 by Olof Björner A SUMMARY OF RECORDING & CONCERT ACTIVITIES, RELEASES, TAPES & BOOKS. © 2000 by Olof Björner All Rights Reserved. This text may be reproduced, re-transmitted, redistributed and otherwise propagated at will, provided that this notice remains intact and in place. So Much Older Then — Bob Dylan 1964 page 2 CONTENTS: 1 INTRODUCTION ................................................................................................................................................... 3 2 THE YEAR AT A GLANCE .................................................................................................................................. 3 3 CALENDAR ............................................................................................................................................................ 3 4 CONCERTS 1964 .................................................................................................................................................... 5 5 RECORDINGS 1964 ............................................................................................................................................... 8 6 ANOTHER SIDE OF BOB DYLAN ...................................................................................................................... 9 7 SONGS 1964 .......................................................................................................................................................... 10 8 SOURCES ............................................................................................................................................................. -

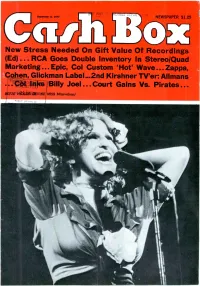

Marketing... Epic, Col Custom 'Hot' Wave

September I, 1973 NEWSPAPER $1.25 New Stress Needed On Gift Value Of Recordings (Ed) ... RCA Goes Double Inventory In StereoIQuad Marketing... Epic, Col Custom 'Hot' Wave... Zappa, Cohen, Glickman Label...2nd Kirshner TV'er: Allurans ...Col Inks Billy Joel ...Court Gains Vs. Pirates... , BtT TE MI VINE /MISS M(arvelous) www.americanradiohistory.com You're the Best Thing That Ever Happened to Me:' It's the best thing to happen to Ray Price since "For the Good Times!' `You're the Best Thing That Ever Happened to Me" is already No 12 with a bullet on the country charts. And more and more Top -40 stat_ons are adding Ray's song to their playlists every week. "You're the Best Thing That Ever Happened to Me" was written by one of today's most prolif_c songwriters, JimWeatherly, whose last two songs,"Neither One of Us (Wants to Be the First to Say Goodbye)" and "Where Peaceful Waters Flow," both be- gan on the country charts and turned into national hits. "You're the Best Thing That Ever Happened to lie=' Ray Prices new single. 4-4 5889 On Columbia Records cot tY1BlA.-jeleARC4S REG 4,41NED IN Sa.: www.americanradiohistory.com /diu /7i/k\\ 1\Q NAM THE INTERNATIONAL MUSIC -RECORD WEEKLY %iriiiW ti UI, Ca,h ox Vol. XXXV - Number 12/September 8, 1973 Publication Office/119 West 57th Street, New York, New York 10019/Telephone: Judson 6-2640/Cable Address Cash Box, N. Y. GEORGE ALBERT President and Publisher MARTY OSTROW Executive Vice President IRV LICHTMAN Vice President and Director of Editorial CHRISTIE BARTER West Coast Manager Editorial New Stress Needed New York KENNY KERNER ARTY GOODMAN DON DROSSELE Hollywood RON BARON On Gift Value BARRY McGOFFIN Research MIKE MARTUCCI Research Manager BOBBY SIEGEL Of Recordings Advertising Some years ago, any number of labels took advantage of the ED ADLUM gift -buying season by formulating merchandising campaigns-some Art Director WOODY HARDING of them elaborate, some modest-that stressed the continuing pleasure derived by the recipient of a recording. -

MDOT-Woodward Avenue Light Rail Transit Project FEIS Archeological

Table of Contents ABSTRACT 1.0 INTRODUCTION........................................................................................................... 1-1 2.0 PROJECT DESCRIPTION ........................................................................................... 2-1 2.1 Alternatives .................................................................................................................. 2-1 2.1.1 No Build Alternative .............................................................................................. 2-1 2.1.2 Locally Preferred Alternative ................................................................................ 2-1 2.1.3 Park and Ride Lot .................................................................................................. 2-3 2.1.4 Traction Power Substations ................................................................................... 2-3 2.1.5 Construction Staging Areas ................................................................................... 2-3 3.0 RESEARCH DESIGN .................................................................................................... 3-1 3.1 Research Goals ............................................................................................................ 3-1 3.2 Background Research ................................................................................................. 3-1 3.2.1 National Historic Landmarks and Historic Districts .............................................. 3-1 3.2.2 Archaeological Sites ............................................................................................. -

Special Issue for July 2013

HIGH TWELVE MONTHLY UPDATE July 2013 Issue Update Published monthly by High Twelve International, Inc. at 743 Palma Drive, Lady Lake, FL, 32159. Telephone numbers (352)-817-0707 or (352) 753-3505. This publication is devoted to the interests of the Wolcott Foundation, Inc., High Twelve International, Inc., and its member clubs for the benefit of Freemasonry and affiliated orders. Contributions of interesting, appropriate editorial matters are welcome. High Twelvians are invited to submit such material for publication. Submit all articles by e-mail. Articles should be received by the deadline date of the 20th day of each month. Updates will be sent out the last of the month. Depending on the volume of articles, they may be carried over to a later date by the Editor. Articles must be sent to the Editor and not called in. Editor: Mervyn J. Harris, PIP, 352-753-3505 (Cell) 352-817-0707, E--mail address: [email protected]. Congratulations to our members and ladies, celebrating their Birthday, Anniversary or other Special Event in July. Don’t forget to make a contribution to the Wolcott Foundation, celebrating your happy event or occasion! SPECIAL ISSUE FOR JULY 2013 HIGHLIGHTS OF THE 92ND INTERNATIONAL CONVENTION! THE WOLCOTT FOUNDATION LUNCHEON HIGHLIGHTS! Prayers are provided by R.W. Reverend Mark Megee, PDDGM & Past President of the Union County High Twelve Club (NJ). He has provided them for our needs and possible use at your club meeting as the opening and closings prayers. Opening Prayer: "Giver to all things, as we gather for this luncheon, we give thanks that we are again permitted to gather in this fellowship. -

Margaret Cho

The ISSUE Detroit’s REC Honors MARGARET CHO WWW.PRIDESOURCE.COM SEPT. 6, 2018 | VOL. 2636 | FREE What is BIKTARVY®? Get HIV support by downloading a free app BIKTARVY is a complete, 1-pill, once-a-day Tell your healthcare provider right away if you get at MyDailyCharge.com prescription medicine used to treat HIV-1 in adults. these symptoms: weakness or being more tired than It can either be used in people who have never taken usual, unusual muscle pain, being short of breath HIV-1 medicines before, or people who are replacing or fast breathing, stomach pain with nausea and their current HIV-1 medicines and whose healthcare vomiting, cold or blue hands and feet, feel dizzy or provider determines they meet certain requirements. lightheaded, or a fast or abnormal heartbeat. BIKTARVY does not cure HIV-1 or AIDS. HIV-1 is � Severe liver problems, which in rare cases can lead the virus that causes AIDS. to death. Tell your healthcare provider right away if you get these symptoms: skin or the white part IMPORTANT SAFETY INFORMATION of your eyes turns yellow, dark “tea-colored” urine, What is the most important information light-colored stools, loss of appetite for several days I should know about BIKTARVY? or longer, nausea, or stomach-area pain. The most common side effects of BIKTARVY in clinical BIKTARVY may cause serious side effects: studies were diarrhea (6%), nausea (5%), and headache � Worsening of hepatitis B (HBV) infection. If you (5%). Tell your healthcare provider if you have any side have both HIV-1 and HBV and stop taking BIKTARVY, effects that bother you or don’t go away. -

MDOT-DTOGS Development of Alternatives

9. EVALUATION OF ALTERNATIVES This section presents the methodology and a summary of the results of the third and final level of evaluation to facilitate the identification of an LPA for the DTOGS project. This section will cite data that is located several appendices to this report because of the volume of details the technical analysis required. Table 9-1 on the following page presents the refined evaluation criteria used in this analysis, which are based on the DTOGS project’s goals and objectives. This third level of analysis also adds a new goal: FTA New Starts Benchmarks. The key performance indicator associated with this goal is the cost effectiveness index (CEI), defined as the cost per new rider. Section 9.2 presents the detailed definition of this additional performance indicator. Following is an outline of Section 9: Evaluation of Alternatives to facilitate review of this section, along with a list of appendices produced for each analysis. Generally, this report presents the methodology first, then a summary of the results next. Section 9.1 Transportation and Mobility - Appendices: (H) Operating Plan; (I) Ridership Forecast Methodology and Results; (J) BRT and LRT Design Guidelines; (K) BRT and LRT Concept Plans and Typical Sections; and (L) Capital Cost Methodology and Results Section 9.2 FTA New Starts Benchmarks - Appendix: (M) Cost Effectiveness Index Calculations – Methodology and Results Section 9.3 Economic Opportunity and Investment - Appendix: (G) Land Use and Economic Impacts of the Gratiot, Michigan, and Woodward -

Summer-Fall Visions06 V6-4

a publication of the W AYNE STATE UNIVERSITY SCHOOL OF SOCIAL WORK www.socialwork.wayne.edu SUMMER/FALL 2006 Class of 2006 Honored at the Annual Dean’s Graduation Recognition Assembly On Saturday April 29, more than 300 BSW and MSW The dean then recognized members of the class degree candidates were honored during the annual who had earned special awards and honors. This Dean’s Graduation Recognition Assembly at the segment was followed by Maxine Thome, Executive Masonic Temple’s Scottish Rite Theatre in Detroit. Director, Michigan Chapter of the NASW, who Phyllis Ivory Vroom, Dean, School of Social Work, welcomed the honorees into the profession of social presided during the event as several invited speakers work. Thome leads an organization that boasts addressed the graduates and their guests. more than 8,000 members in Michigan. Tia Gough, president, Student Organization, Next came the graduation message, delivered by spoke representing the student body, followed by Board of Visitors member Alice G. Thompson, CEO faculty representatives Cassandra Bowers and of Black Family Development, Inc. (BFDI), the private Margaret O. Brunhofer who offered greetings on non-profit counseling agency created in 1978 by the behalf of the BSW and MSW programs respectively. Detroit Chapter of the National Association of Black Graduate Michelle Owens-Hill poses with her proud family Social Workers. By establishing BFDI as a family counseling agency, the Detroit chapter sought to promote and provide quality social work services in Detroit that were culturally relevant and culturally sensitive. BFDI has grown to accommodate the increasing demand for a variety of specialized, family-focused counseling and advocacy services in the community.