The 2000 Presidential Election: Archetype Or Exception?

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

December January the (Let's Get Rid Of

VOLUME 7, NUMBER 6 December 2005 - January 2006 December The (Let’s Get Rid of..?) Endangered Species Act These are great times for By Rosalind Rowe, from notes by Emily B. Roberson, Ph.D. watching waterfowl on wetlands, lakes, Director, Native Plant Conservation Campaign and prairies. The Christmas Bird Count The Threatened and Endangered Species Recovery Act of 2005 (H.R. runs December 14th, 2005 to January 3824) was passed by the U.S. House of Representatives. 5th, 2006; this is its 106th year! (Try The bill removes most of the key protections for listed plants and wildlife www.audubon.org for more info.) under the Endangered Species Act and makes the listing of imperiled species Great horned and barred owls are much more difficult. Perhaps the most disturbing aspect of the bill are its courting; listen for them. restrictions on the types of science – and scientists – that would be considered Manatees congregate at natural eligible to participate in decisions about listing and conserving imperiled plants and springs and industrial warm water sites. other species. Congress is not qualified to legislate science, but HR 3824 will do Bears are still on the move, especially just that. We must get the Senate to reject this legislation. in Collier, Gulf, Hernando, Highlands, Here is how our “representatives” voted, listed by Congressional District Jefferson, Lake, Marion, and Volusia Number: counties. Along the east coast, right whales appear north of Sebastian Inlet Voted YES (GUT the Endangered Voted NO: in Brevard county. Species Act): 03 Corrine Brown (D) Dune sunflowers, some coreopsis, 01 Jeff Miller (R) 16 Mark Foley (R) wild petunia, and passionflower are 02 Allen Boyd (D) 17 Kendrick Meek (D) blooming. -

Reproductions Supplied by EDRS Are the Best That Can Be Made from the Original Document

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 456 856 IR 058 309 AUTHOR Taylor-Furbee, Sondra, Comp.; Kellenberger, Betsy, Comp. TITLE Florida Library Directory with Statistics, 2001. INSTITUTION Florida State Library, Tallahassee. PUB DATE 2001-00-00 NOTE 272p.; For the 2000 directory, see ED 446 777. AVAILABLE FROM Florida Department of State. The Capitol, Tallahassee, FL 32399-0250. Tel: 850-414-5500; Web site: http://www.dos.state.fl.us. For full text: http://dlis.dos.state.fl.us/b1d/Research_Office/BLD_Re search.htm. PUB TYPE Numerical/Quantitative Data (110) Reference Materials Directories/Catalogs (132) EDRS PRICE MF01/PC11 Plus Postage. DESCRIPTORS *Academic Libraries; Access to Information; Elementary Secondary Education; Higher Education; *Libraries; Library Associations; Library Circulation; Library Collections; Library Expenditures; Library Funding; Library Personnel; Library Research; Library Schools; Library Services; *Library Statistics; Public Libraries; School Libraries; State Agencies; Tables (Data) IDENTIFIERS *Florida ABSTRACT The annual "Florida Library Directory with Statistics" is intended to be a tool for library staff to present vital statistical information on budgets, collections, and services to local, state, and national policymakers. As with previous editions, this 2001 edition includes the names, addresses, telephone numbers, and other information for libraries of all types in Florida. In addition, there are statistics to support budgeting, planning, and policy development for Florida's public libraries. The first section consists of listings for Florida Division of Library and Information Services library organizations, councils, and associations. The second section is the directory of libraries, with listings divided by public libraries, academic libraries, special libraries, institutional libraries, and school library media supervisors. The third section consists of a narrative statistical summary of public library data compiled from forms distributed to public libraries in October 2000, as well as selected historical data. -

22Nd Annual Awards Ceremony October 15, 2019

22nd Annual Awards Ceremony October 15, 2019 22nd Annual Awards Ceremony October 15, 2019 Ronald Reagan Building Amphitheater 1300 Pennsylvania Avenue, NW Washington, DC 20004 Council of the Inspectors General on Integrity and Efficiency CIGIE AWARDS–2019 Order OF EVENTS Presentation of Colors and National Anthem Welcoming Remarks The Honorable Paul K. Martin CIGIE Awards Program Co-Chair Inspector General, National Aeronautics and Space Administration Keynote Address The Honorable James F. Bridenstine Administrator, National Aeronautics and Space Administration Special Category Awards Presentation The Honorable Margaret Weichert CIGIE Executive Chair Deputy Director for Management, Office of Management and Budget Alexander Hamilton Award Gaston L. Gianni, Jr. Better Government Award Glenn/Roth Exemplary Service Award Sentner Award for Dedication and Courage June Gibbs Brown Career Achievement Award Award for Individual Accomplishment Barry R. Snyder Joint Award CIGIE Awards Presentation The Honorable Michael E. Horowitz CIGIE Chair, Inspector General, U.S. Department of Justice Allison C. Lerner CIGIE Vice Chair, Inspector General, National Science Foundation Closing Remarks Cathy L. Helm CIGIE Awards Program Co-Chair Inspector General, Smithsonian Institution · iii · Council of the Inspectors General on Integrity and Efficiency NASA ADMINisTraTor JIM BrideNSTINE James Frederick “Jim” Bridenstine was nominated by President Donald Trump, confirmed by the U.S. Senate, and sworn in as NASA’s 13th Administrator on April 23, 2018. Bridenstine was elected in 2012 to represent Oklahoma’s First Congressional District in the U.S. House of Representatives, where he served on the Armed Services Committee and the Science, Space and Technology Committee. Bridenstine’s career in federal service began in the U.S. -

Mike Miller (FL-07) Research Report Th the Following Report Contains Research on Mike Miller, a Republican Candidate in Florida’S 7 District

Mike Miller (FL-07) Research Report th The following report contains research on Mike Miller, a Republican candidate in Florida’s 7 district. Research for this research book was completed by the DCCC’s Research Department in April 2018. By accepting this report, you are accepting responsibility for all information and analysis included. Therefore, it is your responsibility to verify all claims against the original documentation before you make use of it. Make sure you understand the facts behind our conclusions before making any specific charges against anyone. Mike Miller Republican Candidate in Florida’s 7th Congressional District Research Book – 2018 Last Updated April 2018 Prepared by the DCCC Research Department MIKE MILLER (FL-07) Research Book | 1 Table of Contents Thematics .................................................................................................. 3 Career Politician, At Home In Any Swamp ............................................... 4 Miller’s History Of Broken Campaign Pledges & Flip-Flops .................. 15 Key Visuals.............................................................................................. 23 Personal & Professional History .............................................................. 24 Biography ................................................................................................ 25 Personal Finance ...................................................................................... 31 Political Career ....................................................................................... -

In the Supreme Court of Florida Case No. Sc00-2431

IN THE SUPREME COURT OF FLORIDA CASE NO. SC00-2431 DCA Case No. 1D00-4745 ALBERT GORE, JR., ET AL. vs. KATHERINE HARRIS, ETC., ET AL. Appellants Appellees __________________________________________________________ BRIEF OF THE SECRETARY OF STATE AND THE ELECTIONS CANVASSING COMMISSION __________________________________________________________ Deborah K. Kearney Joseph P. Klock, Jr. General Counsel John W. Little, III Kerey Carpenter Alvin F. Lindsay III Assistant General Counsel Robert W. Pittman Florida Department of State Gabriel E. Nieto PL-02 The Capitol Walter J. Harvey Tallahassee, Florida 32399-0250 Ricardo Martinez-Cíd (850) 414-5536 Steel Hector & Davis LLP 215 South Monroe Street, Suite 601 Tallahassee, Florida 32301 (850) 222-2300 (805) 222-8410 Counsel for Appellees TABLE OF CONTENTS TABLE OF AUTHORITIES ......................................iii I. THIS COURT’S DISCRETIONARY JURISDICTION ............. 1 II. SUMMARY OF THE ARGUMENT ............................ 1 III. ARGUMENT ............................................. 2 A. THE ELECTIONS CANVASSING COMMISSION PROPERLY CERTIFIED THE ELECTION RETURNS ........ 2 B. THE APPELLANTS FAILED TO PROVE THAT THE ALLEGED IRREGULARITIES ON A STATEWIDE LEVEL WOULD HAVE CHANGED THE RESULT OF THE ELECTION ............. 3 IV. CONCLUSION .......................................... 10 V. CERTIFICATE OF FONT SIZE ............................. 10 CERTIFICATE OF SERVICE .................................... 12 ii TABLE OF AUTHORITIES CASES Broward County Canvassing Board v. Hogan, 607 So. 2d 508 (Fla. 4th DCA 1992)4 McQuagge v. Conrad, 65 So. 2d 851 (Fla. 1953) ........................ 4 Napp v. Dieffenderfer, 364 So. 2d 534 (Fla. 3d DCA 1978) ................ 4 Nelson v. Robinson, 301 So. 2d 508 (Fla. 2d DCA 1974) ................. 4 Smyth v. Tynes, 412 So. 2d 925 (Fla. 1st DCA 1982) .................... 4 State ex rel. Pooser v. Webster, 170 So. 736 (Fla. 1936) .................. 4 State ex rel. -

FEMA-1545-DR, Florida Portuguese Speaking Population

FEMA-1545-DR, Florida Portuguese Speaking Population AL Holmes County GA MS Santa Rosa County Jackson County Escambia County Okaloosa County Walton County Washington County Nassau County 01 Gadsden County Jeff Miller (R) Jefferson County Hamilton County 04 Calhoun County Ander Crenshaw (R) Leon County Madison County Duval County Bay County Baker County Liberty County Duval County Wakulla County Suwannee County Columbia County 02 Bay County Taylor County Union County Allen Boyd, Jr. (D) Gulf County Lafayette County Bradford County Franklin County Clay County St. Johns County Gilchrist County Alachua County Putnam County 07 Dixie County 06 John L. Mica (R) Clifford B. Stearns (R) Putnam County Flagler County 03 Levy County Corrine Brown (D) Marion County 08 Ric Keller (R) Vol us i a C o un t y Citrus County Lake County 05 24 Seminole County Virginia Brown-Waite (R) Sumter County Tom Feeney (R) Hernando County Orange County Brevard County Pasco County 09 Osceola County Brevard County Michael Bilirakis (R) 10 15 Bill Young (R) Hillsborough County Polk County Dave Weldon (R) Pinellas County 11 12 Legend Jim Davis (D) Legend Adam Putnam (R) Indian River County Manatee County Hardee County 108th Congressional Districts Okeechobee County 13 Highlands County St. Lucie County Katherine Harris (R) Counties 16 Sarasota County DeSoto County Mark Foley (R) Martin County Charlotte County Portuguese speaking persons per sq. mile Glades County Charlotte County Charlotte County 1 - 25 22 E. Clay Shaw, Jr. (R) Palm Beach County 26 - 50 Lee County Hendry County 19 14 23 Robert Wexler (D) 51 - 100 Porter Goss (R) Alcee L. -

Florida U.S. Senate Elections

Florida U.S. Senate Elections Spanish version follows English version. La version en español sigue a la version en inglés 1968 • Edward Gurney, Republican – 55.9% (Winner) • LeRoy Collins – Democrat – 44.1% 1970 • Lawton Chiles, Democrat – 53.9% (Winner) • Bill Cramer, Republican – 46.1% 1974 • Dick Stone, Democrat – 43.4% (Winner) • Jack Eckerd, Republican – 40.9% • John Grady, American – 15.7% 1976 • Lawton Chiles, Democrat – 63.1% (Winner) • John Grady, Republican – 36.9% 1980 • Paula Hawkins, Republican – 51.6% (Winner) • Bill Gunter, Democrat – 48.3% 1982 • Lawton Chiles, Democrat – 61.7% (Winner) • Van Poole, Republican – 38.2% 1986 • Bob Graham, Democrat – 54.7% (Winner) • Paula Hawkins, Republican – 45.3% 1988 • Connie Mack, Republican – 50.4% (Winner) • Buddy MacKay, Democrat – 49.6% 1992 • Bob Graham, Democrat – 65.4% (Winner) • Bill Grant, Republican – 34.6% 1994 • Connie Mack, Republican – 70.5% (Winner) • Hugh Rodham, Democrat – 29.5% 1998 • Bob Graham, Democrat – 62.7% (Winner) • Charlie Crist, Republican – 37.3% 2000 • Bill Nelson, Democrat – 51.0% (Winner) • Bill McCollum, Republican 2004 • Mel Martinez, Republican – 49.4% (Winner) • Betty Castor, Democrat – 48.3% 2006 • Bill Nelson, Democrat – 60.3% (Winner) • Katherine Harris – 38.1% 2010 • Marco Rubio, Republican – 48.9% (Winner) • Charlie Crist, Independent – 29.7% • Kendrick Meek, Democrat – 20.1% 2012 • Bill Nelson, Democrat – 55.2% (Winner) • Connie Mack IV, Republican – 42.2% 2016 • Marco Rubio, Republican – 52.0% (Winner) • Patrick Murphy, Democrat – 44.3% 2018 -

Results: Summary

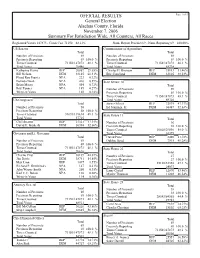

OFFICIAL RESULTS Page 1 of 3 General Election Alachua County, Florida November 7, 2006 Summary For Jurisdiction Wide, All Counters, All Races Registered Voters 147873 - Cards Cast 71150 48.12% Num. Report Precinct 69 - Num. Reporting 69 100.00% US Senator Commissioner of Agriculture Total Total Number of Precincts 69 Number of Precincts 69 Precincts Reporting 69 100.0 % Precincts Reporting 69 100.0 % Times Counted 71150/147873 48.1 % Times Counted 71150/147873 48.1 % Total Votes 70446 Total Votes 68238 Katherine Harris REP 20887 29.65% Charles H. Bronson REP 35113 51.46% Bill Nelson DEM 48125 68.31% Eric Copeland DEM 33125 48.54% Floyd Ray Frazier NPA 223 0.32% Belinda Noah NPA 416 0.59% State Senate 14 Brian Moore NPA 504 0.72% Total Roy Tanner NPA 189 0.27% Number of Precincts 69 Write-in Votes 102 0.14% Precincts Reporting 69 100.0 % Times Counted 71150/147873 48.1 % US Congress 6 Total Votes 69326 Total Steve Oelrich REP 32839 47.37% Number of Precincts 58 Ed Jennings, Jr. DEM 36487 52.63% Precincts Reporting 58 100.0 % Times Counted 59039/119634 49.3 % State House 11 Total Votes 57715 Total Cliff Stearns REP 27321 47.34% Number of Precincts 16 David E. Bruderly DEM 30394 52.66% Precincts Reporting 16 100.0 % Times Counted 16828/29036 58.0 % Governor and Lt. Governor Total Votes 16395 Total David Pope REP 8480 51.72% Number of Precincts 69 Debbie Boyd DEM 7915 48.28% Precincts Reporting 69 100.0 % Times Counted 71150/147873 48.1 % State House 22 Total Votes 70626 Total Charlie Crist REP 30139 42.67% Number of Precincts 27 Jim Davis DEM 38741 54.85% Precincts Reporting 27 100.0 % Max Linn REF 1097 1.55% Times Counted 25120/53350 47.1 % Richard P. -

Gender Bias—Then and Now

Gender Bias—Then and Now Continuing Challenges in the Legal System _________________________________________________ The Report of the Gender Bias Study Implementation Commission _______________________________________________________________ A Study Implementation Commission created by The Supreme Court of Florida December 1996 TABLE OF CONTENTS I. Table of Contents II. Gender Bias Study Implementation Commission Members...................................iii III. Gender Bias Study Implementation Subcommittees...........................................iv IV. Introduction..........................................................................................1 V. Substantive Family Law............................................................................2 VI. Education.............................................................................................4 VII. Legal Profession.....................................................................................5 VIII. Domestic Violence...................................................................................6 XI. Judges and Courts...................................................................................7 X. Criminal Justice System............................................................................9 XI. Conclusion...........................................................................................11 XII. Appendix.............................................................................................13 ii Gender Bias Study Implementation Commission -

Federal Update

Federal Update By Hana Eskra and Charles Elsesser National Elections Federal Budget The national elections in November scrambled In December, incoming leaders of the House House and Senate leadership and committee and Senate Appropriations Committees decided assignments for the coming session and may to continue funding government programs via a garner more support for affordable housing year-long funding resolution until the next fiscal issues. Representative Barney Frank (D- year beginning October 1, 2007. Congress Massachusetts) is now the Chair of the powerful currently has nine appropriations bills that House Committee on Financial Services. This were not passed, including the Transportation, Committee oversees all components of the Treasury, HUD (TTHUD) bill. The measure will nation's housing and financial services sectors be called a “joint funding resolution” because including banking, insurance, real estate, unlike a continuing resolution, it will not Representative Barney Frank public and assisted housing, and securities. It adhere to the funding formula of the lowest of reviews all laws and programs related to the U.S. the House-passed, Senate-passed or FY-06 Department of Housing and Urban Development spending levels but will take into consideration and also ensures the enforcement of housing the needs of individual programs. laws such as the U.S. Housing Act, the Housing and Community Development Act and the While a joint funding resolution is not an ideal Community Reinvestment Act. Representative solution, it will allow HUD along with other Frank was recently asked on PBS’ Nightly agencies and organizations that receive federal Business Report (November 30, 2006) what his funds to plan for this fiscal year and allows top priority was now that it appeared he would housing activist to advocate for increased be chair. -

2000-2002 President Mckay

MESSAGE FROM THE PRESIDENT JOHN M. MCKAY President of the Senate Welcome to the Florida Senate — an institution steeped in tradition and instilled with the greatest sense of responsibility to those it serves. I am both honored and humbled to serve as Senate President for the 2000-2002 term. The opportunities that present themselves and the challenges we face are both exciting and daunt- ing as we address the needs of our nation's fourth largest state. Each of the Senate's 40 members represents a district comprised of constituencies with varied and unique perspectives of individual needs. Our responsibility to all the people of Florida will be to work together toward one common goal — to move the state forward in providing for its citizens through responsible legisla- tion. It has been said that one of the measures by which a society will be judged is the way it cares for its most vulnerable members. The Senate will discuss and debate About the Cover: many issues, but those of foster care, long-term care of the elderly, the homeless and children with developmental disabilities will be of paramount importance during my tenure as President. The Old Capitol, Oil on canvas, 27” x 42” 1982 Artist: Edward Jonas I invite you to read on and learn more about the history of the Florida Senate, its members and the legislative process. I am confident that by working together, Courtesy: The Museum of Florida History we can make Florida a better place to live, work and play as we continue our ven- Used with permission of Katherine Harris, Secretary of State ture into the 21st Century. -

CONGRESSIONAL RECORD—SENATE, Vol. 153, Pt. 17

September 11, 2007 CONGRESSIONAL RECORD—SENATE, Vol. 153, Pt. 17 24193 8/4/2003, Republican National Committee; National Committee; $2,000.00, 5/28/2003, Committee on Commerce, Science, and $2,000.00, 5/28/2003, Bush-Cheney ’04; $2,000.00, Bush-Cheney ’04. Transportation. 5/22//2003, Friends of Mark Foley; $500.00, 4/25/ 3. Children: Joshua M. Siegel: 2007— By Mr. HATCH (for himself and Mr. 2003, Cantor for Congress. $2,300.00, 3/23/2007, John McCain 2008. BENNETT): 2. Spouse: STEPHANIE M. SIEGEL: 2007— 2004—$1,000.00, 10/22/2004, Friends of Kath- S. 2039. A bill to require an assessment of $2,300.00, 4/12/2007, Friends of John Thune; erine Harris; $2,000.00, 10/6/2004, Friends of the plans for the modernization and $4,600.00, 4/3/2007, McConnell Senate Com- Clay Shaw; $2,000.00, 8/27/2004, Friends of sustainment of the land-based, Minuteman mittee; $2,300.00, 3/14/2007, ORRINPAC; Sherwood Boehlert. III intercontinental ballistic missile stra- $2,300.00, 3/1/2007, Citizens for Arlen Specter; 2003—$2,000.00, 9/30/2003, Bush-Cheney ’04 tegic deterrent force, and for other purposes; $200.00, 2/27/2007, John McCain 2008; $2,300.00, Compliance Committee; $2,000.00, 6/25/2003, to the Committee on Armed Services. 2/13/2007, Coleman for Senate; $2,100.00, 1/15/ Bush-Cheney ’04, Inc. By Mr. BINGAMAN (for himself, Mr. 2007, John McCain 2008. Justin M. Siegel: 2007—$2,300.00, 3/23/2007, OBAMA, Mr.