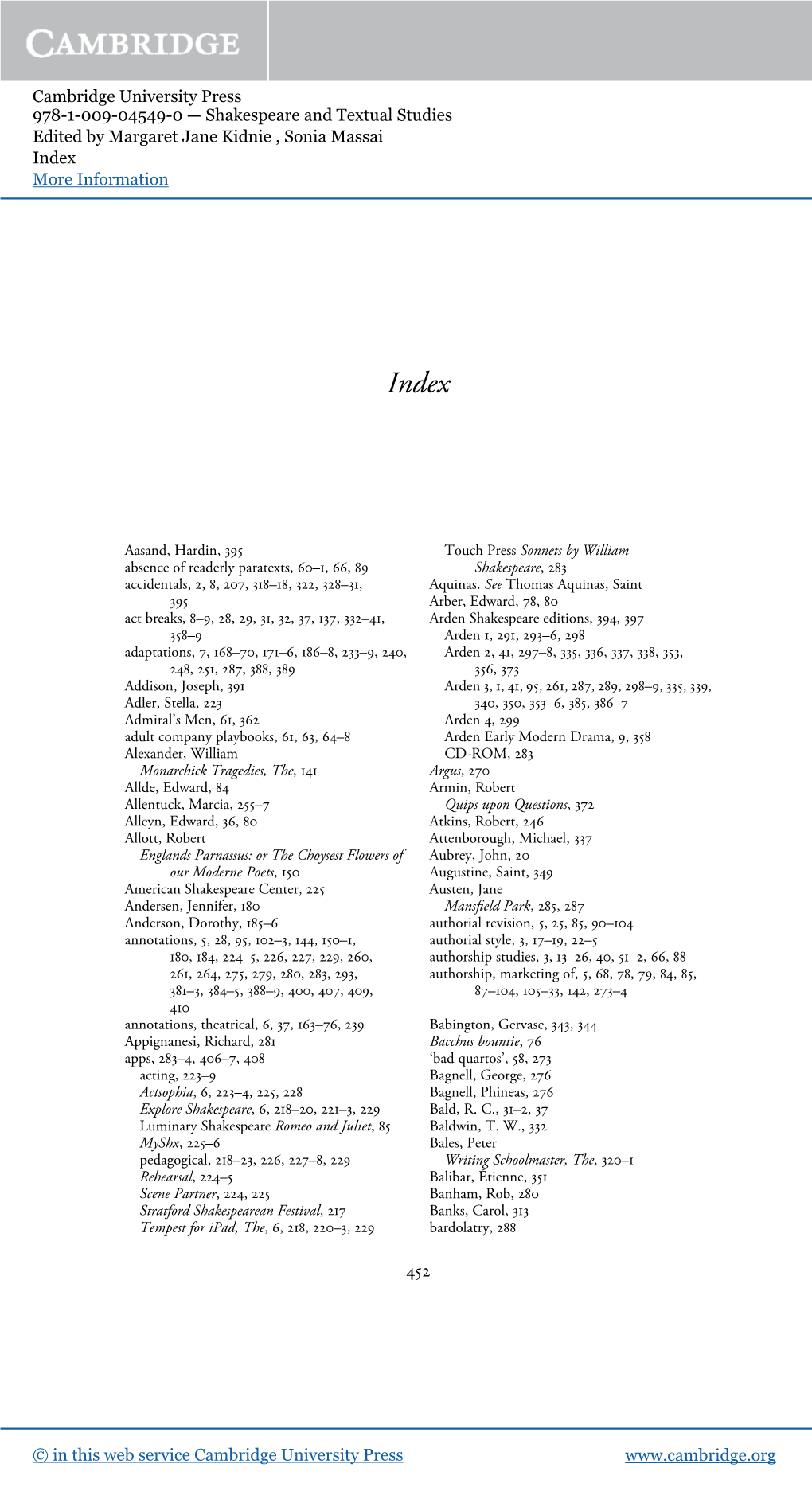

Cambridge University Press 978-1-009-04549-0 — Shakespeare and Textual Studies Edited by Margaret Jane Kidnie , Sonia Massai Index More Information

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Schuler Dissertation Final Document

COUNSEL, POLITICAL RHETORIC, AND THE CHRONICLE HISTORY PLAY: REPRESENTING COUNCILIAR RULE, 1588-1603 DISSERTATION Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of The Ohio State University By Anne-Marie E. Schuler, B.M., M.A. Graduate Program in English The Ohio State University 2011 Dissertation Committee: Professor Richard Dutton, Advisor Professor Luke Wilson Professor Alan B. Farmer Professor Jennifer Higginbotham Copyright by Anne-Marie E. Schuler 2011 ABSTRACT This dissertation advances an account of how the genre of the chronicle history play enacts conciliar rule, by reflecting Renaissance models of counsel that predominated in Tudor political theory. As the texts of Renaissance political theorists and pamphleteers demonstrate, writers did not believe that kings and queens ruled by themselves, but that counsel was required to ensure that the monarch ruled virtuously and kept ties to the actual conditions of the people. Yet, within these writings, counsel was not a singular concept, and the work of historians such as John Guy, Patrick Collinson, and Ann McLaren shows that “counsel” referred to numerous paradigms and traditions. These theories of counsel were influenced by a variety of intellectual movements including humanist-classical formulations of monarchy, constitutionalism, and constructions of a “mixed monarchy” or a corporate body politic. Because the rhetoric of counsel was embedded in the language that men and women used to discuss politics, I argue that the plays perform a kind of cultural work, usually reserved for literature, that reflects, heightens, and critiques political life and the issues surrounding conceptions of conciliar rule. -

Shakespeare Apocrypha” Peter Kirwan

The First Collected “Shakespeare Apocrypha” Peter Kirwan he disparate group of early modern plays still referred to by many Tcritics as the “Shakespeare Apocrypha” take their dubious attributions to Shakespeare from a variety of sources. Many of these attributions are external, such as the explicit references on the title pages of The London Prodigal (1605), A Yorkshire Tragedy (1608), 1 Sir John Oldcastle (1619), The Troublesome Raigne of King John (1622), The Birth of Merlin (1662), and (more ambiguously) the initials on the title pages of Locrine (1595), Thomas Lord Cromwell (1602), and The Puritan (1607). Others, including Edward III, Arden of Faversham, Sir Thomas More, and many more, have been attributed much later on the basis of internal evidence. The first collection of disputed plays under Shakespeare’s name is usually understood to be the second impression of the Third Folio in 1664, which “added seven Playes, never before Printed in Folio.”1 Yet there is some evidence of an interest in dubitanda before the Restoration. The case of the Pavier quar- tos, which included Oldcastle and Yorkshire Tragedy among authentic plays and variant quartos in 1619, has been amply discussed elsewhere as an early attempt to create a canon of texts that readers would have understood as “Shakespeare’s,” despite later critical division of these plays into categories of “authentic” and “spu- rious,” which was then supplanted by the canon presented in the 1623 Folio.2 I would like to attend, however, to a much more rarely examined early collection of plays—Mucedorus, Fair Em, and The Merry Devil of Edmonton, all included in C. -

The Senses in Early Modern England, 1558–1660

2 ‘Dove-like looks’ and ‘serpents eyes’: staging visual clues and early modern aspiration Jackie Watson The traditional sensual hierarchy, in the tradition of Aristotle, gave primacy to the sense of sight.1 However, there is much evidence to suggest that the judgements of many late Elizabethans were more ambivalent. In this chapter I shall ask how far an early modern playgoer could trust the evidence of his or her own eyes. Sight was, at the same time, the most perfect of senses and the potential entry route for evil. It was the means by which men and women fell in love, and the means by which they established a false appearance. It was both highly valorized and deeply distrusted. Nowhere was it more so than at court, where men depended, for preferment and even survival, on the images they projected to others, but where their manipulation of one another was often interpreted as morally dubious. In their depictions of the performative nature of court life and the achievement of early modern ambition, late Elizabethan plays were engaged in this debate, and stage and court developed analogous modes of image projection. Here, I shall explore conflicting philosophical and early scientific attitudes to visual clues, before examining the moral judgements of seeing in late Elizabethan drama. Examples from these plays show appear- ance as a practical means of fulfilling courtly aspiration, but also suggest the moral concern surrounding such ambitions. These issues were of personal interest to the ambitious, playgoing young gentlemen of the Inns of Court. Finally, suggesting the irony of such a debate in a medium which itself relies so much upon appearance and deception, I shall conclude by considering the ways in which writers for the ‘new technology’ of the playhouse were engaged in guiding their audiences both in how to see, and how to interpret the validity of the visual. -

Could Shakespeare Think Like a Lawyer? How Inheritance Law Issues in Hamlet May Shed Light on the Authorship Question

University of Miami Law Review Volume 57 Number 2 Article 4 1-1-2003 Could Shakespeare Think Like a Lawyer? How Inheritance Law Issues in Hamlet May Shed Light on the Authorship Question Thomas Regnier Follow this and additional works at: https://repository.law.miami.edu/umlr Recommended Citation Thomas Regnier, Could Shakespeare Think Like a Lawyer? How Inheritance Law Issues in Hamlet May Shed Light on the Authorship Question, 57 U. Miami L. Rev. 377 (2003) Available at: https://repository.law.miami.edu/umlr/vol57/iss2/4 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Journals at University of Miami School of Law Institutional Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in University of Miami Law Review by an authorized editor of University of Miami School of Law Institutional Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. COMMENT Could Shakespeare Think Like a Lawyer? How Inheritance Law Issues in Hamlet May Shed Light on the Authorship Question Shakespeare couldn't have written Shakespeare's works, for the reason that the man who wrote them was limitlessly familiar with the laws, and the law-courts, and law-proceedings, and lawyer-talk, and lawyer-ways-and if Shakespeare was possessed of the infinitely- divided star-dust that constituted this vast wealth, how did he get it, and where, and when? . [A] man can't handle glibly and easily and comfortably and successfully the argot of a trade at which he has not personally served. He will make mistakes; he will not, and can- not, get the trade-phrasings precisely and exactly right; and the moment he departs, by even a shade, from a common trade-form, the reader who has served that trade will know the writer hasn't. -

The Shakespeare Apocrypha and Canonical Expansion in the Marketplace

The Shakespeare Apocrypha and Canonical Expansion in the Marketplace Peter Kirwan 1 n March 2010, Brean Hammond’s new edition of Lewis Theobald’s Double Falsehood was added to the ongoing third series of the Arden Shakespeare, prompting a barrage of criticism in the academic press I 1 and the popular media. Responses to the play, which may or may not con- tain the “ghost”2 of Shakespeare and Fletcher’s Cardenio, have dealt with two issues: the question of whether Double Falsehood is or is not a forgery;3 and if the latter, the question of how much of it is by Shakespeare. This second question as a criterion for canonical inclusion is my starting point for this paper, as scholars and critics have struggled to define clearly the boundar- ies of, and qualifications for, canonicity. James Naughtie, in a BBC radio interview with Hammond to mark the edition’s launch, suggested that a new attribution would only be of interest if he had “a big hand, not just was one of the people helping to throw something together for a Friday night.”4 Naughtie’s comment points us toward an important, unqualified aspect of the canonical problem—how big does a contribution by Shakespeare need to be to qualify as “Shakespeare”? The act of inclusion in an editedComplete Works popularly enacts the “canonization” of a work, fixing an attribution in print and commodifying it within a saleable context. To a very real extent, “Shakespeare” is defined as what can be sold as Shakespearean. Yet while canonization operates at its most fundamental as a selection/exclusion binary, collaboration compli- cates the issue. -

Dramatic Form in the Early Modern English History Play

THE CATHOLIC UNIVERSITY OF AMERICA Dramatic Form in the Early Modern English History Play A DISSERTATION Submitted to the Faculty of the Department of English School of Arts and Sciences Of The Catholic University of America In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements For the Degree Doctor of Philosophy © Copyright All Rights Reserved By Shaun Stiemsma Washington, DC 2017 Dramatic Form in the Early Modern English History Play Shaun Stiemsma, Ph.D. Director: Michael Mack, Ph.D. The early modern history play has been assumed to exist as an independent genre at least since Shakespeare’s first folio divided his plays into comedies, tragedies, and histories. However, history has never—neither during the period nor in literary criticism since—been satisfactorily defined as a distinct dramatic genre. I argue that this lack of definition obtains because early modern playwrights did not deliberately create a new genre. Instead, playwrights using history as a basis for drama recognized aspects of established genres in historical source material and incorporated them into plays about history. Thus, this study considers the ways in which playwrights dramatizing history use, manipulate, and invert the structures and conventions of the more clearly defined genres of morality, comedy, and tragedy. Each chapter examines examples to discover generic patterns present in historical plays and to assess the ways historical materials resist the conceptions of time suggested by established dramatic genres. John Bale’s King Johan and the anonymous Woodstock both use a morality structure on a loosely contrived history but cannot force history to conform to the apocalyptic resolution the genre demands. -

Editorial Treatment of the Shakespeare Apocrypha

Egan, Gabriel. 2004j. 'Editorial Treatment of the Shakespeare Apocrypha, 1664-1737': A Paper Delivered at the Conference 'Leviathan to Licensing Act (The Long Restoration, 1650-1737): Theatre, Print and Their Contexts' at Loughborough University, 15-16 September Editorial treatment of the Shakespeare apocrypha, 1664-1737 by Gabriel Egan The third edition (F3) of the collected plays of Shakespeare appeared in 1663, and to its second issue the following year was added a particularly disreputable group of plays comprised Pericles, The London Prodigal, Sir John Oldcastle, A Yorkshire Tragedy, Thomas Lord Cromwell, The Puritan, and Locrine. Of these, only Pericles remains in the accepted Shakespeare canon, the edges of which are imprecisely defined. (At the moment it is unclear whether Edward 3 is in or out.) The landmark event for defining the Shakespeare canon was the publication of the 1623 First Folio (F1), with which, as Stanley Wells and Gary Taylor put it, "the substantive history of Shakespeare's dramatic texts virtually comes to an end" (Wells et al. 1987, 52). Only one more genuine Shakespeare play was first printed after 1623: The Two Noble Kinsmen, which appeared in a quarto of 1634 whose title-page attributed it to Shakespeare and Fletcher, "Gent[lemen]" (Fletcher & Shakespeare 1634, A1r). Perhaps inclusion in F1 should not be an important criterion for us and we should put more weight on such facts as Pericles's appearing in quarto in 1609 with a titlepage that claimed it was by William Shakespeare. But the same can be said for other plays that got added to the Folio in 1663: The London Prodigal, Sir John Oldcastle, and A Yorkshire Tragedy were printed in early quartos that named their author as William Shakespeare and the other three in quartos that named "W.S". -

The Shakespeare Apocrypha and Canonical Expansion in the Marketplace. Philological Quarterly, 91 (2)

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Nottingham ePrints Kirwan, Peter (2012) The Shakespeare apocrypha and canonical expansion in the marketplace. Philological Quarterly, 91 (2). pp. 247-275. ISSN 2169-5342 Access from the University of Nottingham repository: http://eprints.nottingham.ac.uk/37577/1/Kirwan%20-%20Shakespeare%20Apocrypha %20and%20Canonical%20Expansion.pdf Copyright and reuse: The Nottingham ePrints service makes this work by researchers of the University of Nottingham available open access under the following conditions. This article is made available under the University of Nottingham End User licence and may be reused according to the conditions of the licence. For more details see: http://eprints.nottingham.ac.uk/end_user_agreement.pdf A note on versions: The version presented here may differ from the published version or from the version of record. If you wish to cite this item you are advised to consult the publisher’s version. Please see the repository url above for details on accessing the published version and note that access may require a subscription. For more information, please contact [email protected] The Shakespeare Apocrypha and Canonical Expansion in the Marketplace Peter Kirwan 1 n March 2010, Brean Hammond’s new edition of Lewis Theobald’s Double Falsehood was added to the ongoing third series of the Arden Shakespeare, prompting a barrage of criticism in the academic press I 1 and the popular media. Responses to the play, which may or may not con- tain the “ghost”2 of Shakespeare and Fletcher’s Cardenio, have dealt with two issues: the question of whether Double Falsehood is or is not a forgery;3 and if the latter, the question of how much of it is by Shakespeare. -

William Shakespeare 1 William Shakespeare

William Shakespeare 1 William Shakespeare William Shakespeare The Chandos portrait, artist and authenticity unconfirmed. National Portrait Gallery, London. Born Baptised 26 April 1564 (birth date unknown) Stratford-upon-Avon, Warwickshire, England Died 23 April 1616 (aged 52) Stratford-upon-Avon, Warwickshire, England Occupation Playwright, poet, actor Nationality English Period English Renaissance Spouse(s) Anne Hathaway (m. 1582–1616) Children • Susanna Hall • Hamnet Shakespeare • Judith Quiney Relative(s) • John Shakespeare (father) • Mary Shakespeare (mother) Signature William Shakespeare (26 April 1564 (baptised) – 23 April 1616)[1] was an English poet and playwright, widely regarded as the greatest writer in the English language and the world's pre-eminent dramatist.[2] He is often called England's national poet and the "Bard of Avon".[3][4] His extant works, including some collaborations, consist of about 38 plays,[5] 154 sonnets, two long narrative poems, and a few other verses, the authorship of some of which is uncertain. His plays have been translated into every major living language and are performed more often than those of any other playwright.[6] Shakespeare was born and brought up in Stratford-upon-Avon. At the age of 18, he married Anne Hathaway, with whom he had three children: Susanna, and twins Hamnet and Judith. Between 1585 and 1592, he began a successful career in London as an actor, writer, and part-owner of a playing company called the Lord Chamberlain's Men, later known as the King's Men. He appears to have retired to Stratford around 1613 at age 49, where he died three years later. -

Renaissance Drama- Unit I

Renaissance Drama- Unit I 1 Background 2 The Elizabethan and Jacobean Ages 3 Offshoots of Renaissance Drama 4 Major poets of this Age 5 Elizabethan Prose 6 Elizabethan Drama 7 Other Playwrights during this period 8 Conclusion 9 Important Questions 1 Background 1.1 Introduction to Renaissance Drama: Renaissance" literally means "rebirth." It refers especially to the rebirth of learning that began in Italy in the fourteenth century, spread to the north, including England, by the sixteenth century, and ended in the north in the mid-seventeenth century (earlier in Italy). During this period, there was an enormous renewal of interest in and study of classical antiquity. Yet the Renaissance was more than a "rebirth." It was also an age of new discoveries, both geographical (exploration of the New World) and intellectual. Both kinds of discovery resulted in changes of tremendous import for Western civilization. In science, for example, Copernicus (1473-1543) attempted to prove that the sun rather than the earth was at the center of the planetary system, thus radically altering the cosmic world view that had dominated antiquity and the Middle Ages. In religion, Martin Luther (1483-1546) challenged and ultimately caused the division of one of the major institutions that had united Europe throughout the Middle Ages--the Church. In fact, Renaissance thinkers often thought of themselves as ushering in the modern age, as distinct from the ancient and medieval eras Study of the Renaissance might well center on five interrelated issues. First, although Renaissance thinkers often tried to associate themselves with classical antiquity and to dissociate themselves from the Middle Ages, important continuities with their recent past, such as belief in the Great Chain of Being, were still much in evidence. -

Heterodox Drama: Theater in Post-Reformation London

Heterodox Drama: Theater in Post-Reformation London Musa Gurnis-Farrell Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of Arts and Sciences COLUMBIA UNIVERSITY 2011 © 2011 Musa Gurnis-Farrell All rights reserved ABSTRACT Heterodox Drama: Theater in Post-Reformation London Musa Gurnis-Farrell In “Heterodox Drama: Theater in Post-Reformation London,” I argue that the specific working practices of the theater industry generated a body of drama that combines the varied materials of post-Reformation culture in hybrid fantasies that helped audiences emotionally negotiate and productively re-imagine early modern English religious life. These practices include: the widespread recycling of stock figures, scenarios, and bits of dialogue to capitalize on current dramatic trends; the collaboration of playwrights and actors from different religious backgrounds within theater companies; and the confessionally diverse composition of theater audiences. By drawing together a heterodox conglomeration of Londoners in a discursively capacious cultural space, the theaters created a public. While the public sphere that emerges from early modern theater culture helped audience members process religious material in politically significant ways, it did so not primarily through rational-critical thought but rather through the faculties of affect and imagination. The theater was a place where the early modern English could creatively reconfigure existing confessional identity categories, and emotionally experiment with the rich ideological contradictions of post-Reformation life. ! Table of Contents Introduction: Heterodoxy and Early Modern Theater . 1 Chapter One: “Frequented by Puritans and Papists”: Heterodox Audiences . 23 Chapter Two: Religious Polemic from Print into Plays . 64 Chapter Three: Martyr Acts: Playing with Foxe’s Martyrs on the Public Stage . -

Forgotten Histories Abstracts Leader: Marisa Cull, Randolph-Macon College 1

2017 SAA Seminar: Forgotten Histories Abstracts Leader: Marisa Cull, Randolph-Macon College 1 Mark Bayer Nobody’s Business Sometimes, histories were meant to be forgotten. This would seem to be the case with the anonymous Nobody and Somebody: With the True Chronicle History of Elidure, first staged at the Red Bull sometime around 1606. While this play might not qualify as a history in the modern sense of the term, it is loosely based on the exploits of the legendary King Elidure as recounted by Geoffrey of Monmouth, features the political intrigue common to this genre, and is set in a panoply of London locales that would be familiar to its audience. It’s no coincidence, I think, that this play was performed at the Red Bull, an often- neglected venue we usually associate with tradesmen and apprentices—the ‘nobodies’ of Jacobean England. The play, I argue, appeals specifically to this audience precisely because it inserts Nobody as a significant historical figure, one who eventually triumphs over Somebody. Part of Nobody’s attraction is the fluidity with which he is able to move within different social settings, be they in country, city, or court. His ambiguous agential status also has important economic implications; like Robin Hood, he redistributes wealth to the needy, and he does so more efficiently than the official channels designed to relieve London’s poor. Nobody, I claim, is emblematic of market efficiency at a time when commerce—both in the play and in the city— was curtailed by extensive monopoly power exercised over several key industries.