July/August, 2017

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Flora of Oakmont Park, City of Fort Worth Tarrant Co

Flora of Oakmont Park, City of Fort Worth Tarrant Co. Updated 09 April 2015 150 species Oakmont Park FLOWER STATE/FED FAMILY OLD FAMILY LATIN NAME COMMON NAME BLOOM PERIOD Expr1006 COLOR RANK Amaryllidaceae Alliaceae=Liliaceae Allium drummondii Drummond's Onion ++345++++++++++ White/Pink Amaryllidaceae Alliaceae=Liliaceae Nothoscordum bivalve Crow-Poison +F345+++910++++ White Apiaceae Chaerophyllum tainturieri var. Smooth Chervil ++34+++++++++++ White tainturieri Apiaceae Cymopterus macrohizus Bigroot Cymopterus JF34+++++++++++ White/Pink Apiaceae Eryngium leavenworthii Leavenworth Eryngo ++++++789++++++ Purple Apiaceae Polytaenia nuttallii=texana Prairie Parsley +++45++++++++++ Yellow Apiaceae Sanicula canadensis Canada Sanicle +++456+++++++++ White Apiaceae Torilis arvensis Hedge Parsley +++456+++++++++ White Apiaceae Torilis nodosa Knotted Hedge-Parsley +++456+++++++++ White Apocynaceae Asclepidaceae Asclepias asperula ssp. capricornu Antelope Horns +++45678910++++ White Aquifoliaceae Ilex decidua Possum Haw ++345++++++++++ White Asparagaceae Agavaceae Yucca arkansana Arkansas Yucca +++45++++++++++ White Asparagaceae Agavaceae Yucca necopina Glen Rose Yucca ++++5++++++++++ White S1S2 S1S2 Asparagaceae Agavaceae Yucca pallida Pale Leaf Yucca ++++5++++++++++ White S3 S3 Asteraceae Ambrosia psilostachya Western Ragweed +++++++891011++ Inconspicuous Asteraceae Amphiachyris Common Broomweed ++++++7891011++ Yellow dracunculoides=Gutierrezia Asteraceae Artemisia ludoviciana ssp. mexicana Mexican Sagebrush +++++++++1011++ Yellowish White Asteraceae -

Phylogeny and Evolution of Achenial Trichomes In

Luebert & al. • Achenial trichomes in the Lucilia-group (Asteraceae) TAXON 66 (5) • October 2017: 1184–1199 Phylogeny and evolution of achenial trichomes in the Lucilia-group (Asteraceae: Gnaphalieae) and their systematic significance Federico Luebert,1,2,3 Andrés Moreira-Muñoz,4 Katharina Wilke2 & Michael O. Dillon5 1 Freie Universität Berlin, Institut für Biologie, Botanik, Altensteinstraße 6, 14195 Berlin, Germany 2 Universität Bonn, Nees-Institut für Biodiversität der Pflanzen, Meckenheimer Allee 170, 53115 Bonn, Germany 3 Universidad de Chile, Departamento de Silvicultura y Conservación de la Naturaleza, Santiago, Chile 4 Pontificia Universidad Católica de Valparaíso, Instituto de Geografía, Avenida Brasil 2241, Valparaíso, Chile 5 The Field Museum, Integrative Research Center, 1400 South Lake Shore Drive, Chicago, Illinois 60605, U.S.A. Author for correspondence: Federico Luebert, [email protected] ORCID FL, http://orcid.org/0000000322514056; MOD, http://orcid.org/0000000275120766 DOI https://doi.org/10.12705/665.11 Abstract The Gnaphalieae (Asteraceae) are a cosmopolitan tribe with around 185 genera and 2000 species. The New World is one of the centers of diversity of the tribe with 24 genera and over 100 species, most of which form a clade called the Luciliagroup with 21 genera. However, the generic classification of the Luciliagroup has been controversial with no agreement on delimitation or circumscription of genera. Especially controversial has been the taxonomic value of achenial trichomes and molecular studies have shown equivocal results so far. The major aims of this paper are to provide a nearly complete phylogeny of the Lucilia group at generic level and to discuss the evolutionary trends and taxonomic significance of achenial trichome morphology. -

How Many of Cassini Anagrams Should There Be? Molecular

TAXON 59 (6) • December 2010: 1671–1689 Galbany-Casals & al. • Systematics and phylogeny of the Filago group How many of Cassini anagrams should there be? Molecular systematics and phylogenetic relationships in the Filago group (Asteraceae, Gnaphalieae), with special focus on the genus Filago Mercè Galbany-Casals,1,3 Santiago Andrés-Sánchez,2,3 Núria Garcia-Jacas,1 Alfonso Susanna,1 Enrique Rico2 & M. Montserrat Martínez-Ortega2 1 Institut Botànic de Barcelona (CSIC-ICUB), Pg. del Migdia s.n., 08038 Barcelona, Spain 2 Departamento de Botánica, Facultad de Biología, Universidad de Salamanca, 37007 Salamanca, Spain 3 These authors contributed equally to this publication. Author for correspondence: Mercè Galbany-Casals, [email protected] Abstract The Filago group (Asteraceae, Gnaphalieae) comprises eleven genera, mainly distributed in Eurasia, northern Africa and northern America: Ancistrocarphus, Bombycilaena, Chamaepus, Cymbolaena, Evacidium, Evax, Filago, Logfia, Micropus, Psilocarphus and Stylocline. The main morphological character that defines the group is that the receptacular paleae subtend, and more or less enclose, the female florets. The aims of this work are, with the use of three chloroplast DNA regions (rpl32-trnL intergenic spacer, trnL intron, and trnL-trnF intergenic spacer) and two nuclear DNA regions (ITS, ETS), to test whether the Filago group is monophyletic; to place its members within Gnaphalieae using a broad sampling of the tribe; and to investigate in detail the phylogenetic relationships among the Old World members of the Filago group and provide some new insight into the generic circumscription and infrageneric classification based on natural entities. Our results do not show statistical support for a monophyletic Filago group. -

Vascular Plants and a Brief History of the Kiowa and Rita Blanca National Grasslands

United States Department of Agriculture Vascular Plants and a Brief Forest Service Rocky Mountain History of the Kiowa and Rita Research Station General Technical Report Blanca National Grasslands RMRS-GTR-233 December 2009 Donald L. Hazlett, Michael H. Schiebout, and Paulette L. Ford Hazlett, Donald L.; Schiebout, Michael H.; and Ford, Paulette L. 2009. Vascular plants and a brief history of the Kiowa and Rita Blanca National Grasslands. Gen. Tech. Rep. RMRS- GTR-233. Fort Collins, CO: U.S. Department of Agriculture, Forest Service, Rocky Mountain Research Station. 44 p. Abstract Administered by the USDA Forest Service, the Kiowa and Rita Blanca National Grasslands occupy 230,000 acres of public land extending from northeastern New Mexico into the panhandles of Oklahoma and Texas. A mosaic of topographic features including canyons, plateaus, rolling grasslands and outcrops supports a diverse flora. Eight hundred twenty six (826) species of vascular plant species representing 81 plant families are known to occur on or near these public lands. This report includes a history of the area; ethnobotanical information; an introductory overview of the area including its climate, geology, vegetation, habitats, fauna, and ecological history; and a plant survey and information about the rare, poisonous, and exotic species from the area. A vascular plant checklist of 816 vascular plant taxa in the appendix includes scientific and common names, habitat types, and general distribution data for each species. This list is based on extensive plant collections and available herbarium collections. Authors Donald L. Hazlett is an ethnobotanist, Director of New World Plants and People consulting, and a research associate at the Denver Botanic Gardens, Denver, CO. -

Mississippi Natural Heritage Program Special Plants - Tracking List -2018

MISSISSIPPI NATURAL HERITAGE PROGRAM SPECIAL PLANTS - TRACKING LIST -2018- Approximately 3300 species of vascular plants (fern, gymnosperms, and angiosperms), and numerous non-vascular plants may be found in Mississippi. Many of these are quite common. Some, however, are known or suspected to occur in low numbers; these are designated as species of special concern, and are listed below. There are 495 special concern plants, which include 4 non- vascular plants, 28 ferns and fern allies, 4 gymnosperms, and 459 angiosperms 244 dicots and 215 monocots. An additional 100 species are designated “watch” status (see “Special Plants - Watch List”) with the potential of becoming species of special concern and include 2 fern and fern allies, 54 dicots and 44 monocots. This list is designated for the primary purposes of : 1) in environmental assessments, “flagging” of sensitive species that may be negatively affected by proposed actions; 2) determination of protection priorities of natural areas that contain such species; and 3) determination of priorities of inventory and protection for these plants, including the proposed listing of species for federal protection. GLOBAL STATE FEDERAL SPECIES NAME COMMON NAME RANK RANK STATUS BRYOPSIDA Callicladium haldanianum Callicladium Moss G5 SNR Leptobryum pyriforme Leptobryum Moss G5 SNR Rhodobryum roseum Rose Moss G5 S1? Trachyxiphium heteroicum Trachyxiphium Moss G2? S1? EQUISETOPSIDA Equisetum arvense Field Horsetail G5 S1S2 FILICOPSIDA Adiantum capillus-veneris Southern Maidenhair-fern G5 S2 Asplenium -

Flora Mediterranea 26

FLORA MEDITERRANEA 26 Published under the auspices of OPTIMA by the Herbarium Mediterraneum Panormitanum Palermo – 2016 FLORA MEDITERRANEA Edited on behalf of the International Foundation pro Herbario Mediterraneo by Francesco M. Raimondo, Werner Greuter & Gianniantonio Domina Editorial board G. Domina (Palermo), F. Garbari (Pisa), W. Greuter (Berlin), S. L. Jury (Reading), G. Kamari (Patras), P. Mazzola (Palermo), S. Pignatti (Roma), F. M. Raimondo (Palermo), C. Salmeri (Palermo), B. Valdés (Sevilla), G. Venturella (Palermo). Advisory Committee P. V. Arrigoni (Firenze) P. Küpfer (Neuchatel) H. M. Burdet (Genève) J. Mathez (Montpellier) A. Carapezza (Palermo) G. Moggi (Firenze) C. D. K. Cook (Zurich) E. Nardi (Firenze) R. Courtecuisse (Lille) P. L. Nimis (Trieste) V. Demoulin (Liège) D. Phitos (Patras) F. Ehrendorfer (Wien) L. Poldini (Trieste) M. Erben (Munchen) R. M. Ros Espín (Murcia) G. Giaccone (Catania) A. Strid (Copenhagen) V. H. Heywood (Reading) B. Zimmer (Berlin) Editorial Office Editorial assistance: A. M. Mannino Editorial secretariat: V. Spadaro & P. Campisi Layout & Tecnical editing: E. Di Gristina & F. La Sorte Design: V. Magro & L. C. Raimondo Redazione di "Flora Mediterranea" Herbarium Mediterraneum Panormitanum, Università di Palermo Via Lincoln, 2 I-90133 Palermo, Italy [email protected] Printed by Luxograph s.r.l., Piazza Bartolomeo da Messina, 2/E - Palermo Registration at Tribunale di Palermo, no. 27 of 12 July 1991 ISSN: 1120-4052 printed, 2240-4538 online DOI: 10.7320/FlMedit26.001 Copyright © by International Foundation pro Herbario Mediterraneo, Palermo Contents V. Hugonnot & L. Chavoutier: A modern record of one of the rarest European mosses, Ptychomitrium incurvum (Ptychomitriaceae), in Eastern Pyrenees, France . 5 P. Chène, M. -

Pollen Morphology of Tribes Gnaphalieae, Helenieae, Plucheeae and Senecioneae (Subfamily Asteroideae) of Compositae from Egypt

American Journal of Plant Sciences, 2011, 2, 120-133 doi:10.4236/ajps.2011.22014 Published Online June 2011 (http://www.SciRP.org/journal/ajps) Pollen Morphology of Tribes Gnaphalieae, Helenieae, Plucheeae and Senecioneae (Subfamily Asteroideae) of Compositae from Egypt Ahmed Kamal El-Deen Osman Faculty of Science, Botany Department, South Valley University, Qena, Egypt. Email: [email protected] Received October 10th, 2010; revised December 9th, 2010; accepted December 20th, 2010. ABSTRACT POLLEN morphology of twenty five species representing 12 genera of tribes Gnaphalieae, Helenieae, Plucheeae and Senecioneae (Asteroideae: Asteraceae) was investigated using light and scanning electron microscopy. The genera are Phagnalon, Filago, Gnaphalium, Helichrysum, Homognaphalium, Ifloga, Lasiopogon, Pseudognaphalium, Flaveria, Tagetes, Sphaeranthus and Senecio. Two pollen types were recognized viz. Senecio pollen type and Filago pollen type. Description of each type, a key to the investigated taxa as well as LM and SEM micrographs of pollen grains are pro- vided. Keywords: Pollen, Morphology, Asteroideae, Asteraceae, Egypt 1. Introduction ture involves the foot layer and the outer layer of the endexine and the endoaperture involves the inner layer of Gnaphalieae, Helenieae, Plucheeae and Senecioneae (As- the endoxine. The intine is thickened considerably in teroideae: Asteraceae) are of the well represented tribes Anthemideae near the aperture. Reference [8] described in Egypt, where 12 genera with about thirty five species are native in -

Mockingbird Trail April 23, 2014 Art Gibson & Jack Beckett 1. Allium

Mockingbird Trail April 23, 2014 Art Gibson & Jack Beckett 1. Allium canadense var. fraseri, wild onion, wild garlic. Native perennial herb that spreads largely by seed 2. Allium drummondii, Drummond’s onion. Native bulbous perennial herb with pink flowers 3. Anemone berlandieri (A. heterophylla), ten-petal anemone, windflower. Native perennial herb with 3-parted leaves and on a stalk a solitary flower with eleven to seventeen white to purple petals (here not ten) 4. Aristida purpurea var. longiseta, red threeawn. Native perennial bunchgrass with purple-red inflorescence having a spikelet with only one floret, that with three awns on each lemma 5. Asclepias asperula subsp. capricornu, antelope horns, Native perennial herbs with several shoots close to the ground, fantastic flowers pollinated by wasps and plants used by butterflies 6. Baccharis neglecta, willow baccharis, Roosevelt-weed. Native shrub but terribly invasive, common in Sun City, with sweetly fragrant flowers in late summer and clouds of windborne fruits with small parachutes 7. Bouchetia rigida, erect bouchetia. Native perennial herb with white, funnel- shaped flowers, closely related to the genus of tobacco but not with the foul odor 8. Bromus catharticus, rescue grass. Perennial herb introduced from the Old World and widely established in grassy areas throughout the region; spikelets have very short awns 9. Bromus japonicus, Japanese brome. Introduced annual from Eurasia with slender, awned spikelets 10. Buglossoides arvensis, field bugloss. Native annual with tiny white flowers, of open and grassy sites. 11. Carex planostachys, cedar sedge?. Native perennial herb of cedar brakes; with the flowers clustered at the top of the stalk well above the foliage 12. -

Ecological Checklist of the Missouri Flora for Floristic Quality Assessment

Ladd, D. and J.R. Thomas. 2015. Ecological checklist of the Missouri flora for Floristic Quality Assessment. Phytoneuron 2015-12: 1–274. Published 12 February 2015. ISSN 2153 733X ECOLOGICAL CHECKLIST OF THE MISSOURI FLORA FOR FLORISTIC QUALITY ASSESSMENT DOUGLAS LADD The Nature Conservancy 2800 S. Brentwood Blvd. St. Louis, Missouri 63144 [email protected] JUSTIN R. THOMAS Institute of Botanical Training, LLC 111 County Road 3260 Salem, Missouri 65560 [email protected] ABSTRACT An annotated checklist of the 2,961 vascular taxa comprising the flora of Missouri is presented, with conservatism rankings for Floristic Quality Assessment. The list also provides standardized acronyms for each taxon and information on nativity, physiognomy, and wetness ratings. Annotated comments for selected taxa provide taxonomic, floristic, and ecological information, particularly for taxa not recognized in recent treatments of the Missouri flora. Synonymy crosswalks are provided for three references commonly used in Missouri. A discussion of the concept and application of Floristic Quality Assessment is presented. To accurately reflect ecological and taxonomic relationships, new combinations are validated for two distinct taxa, Dichanthelium ashei and D. werneri , and problems in application of infraspecific taxon names within Quercus shumardii are clarified. CONTENTS Introduction Species conservatism and floristic quality Application of Floristic Quality Assessment Checklist: Rationale and methods Nomenclature and taxonomic concepts Synonymy Acronyms Physiognomy, nativity, and wetness Summary of the Missouri flora Conclusion Annotated comments for checklist taxa Acknowledgements Literature Cited Ecological checklist of the Missouri flora Table 1. C values, physiognomy, and common names Table 2. Synonymy crosswalk Table 3. Wetness ratings and plant families INTRODUCTION This list was developed as part of a revised and expanded system for Floristic Quality Assessment (FQA) in Missouri. -

Red-Tipped Cudweed

Watsonia 22: 251-260 (1999) 251 Conservation of Britain's biodiversity: Filago lutescens Jordan (Asteraceae), Red-tipped cudweed T. c. G. RICH Department of Biodiversity and Systematic Biology, National Museum and Gallery of Wales, CardiffCFl3NP ABSTRACT This paper summarizes the conservation work being carried out on Filago lutescens L. (Asteraceae), Red-tipped cudweed, a rare, statutorily protected species in Britain. It is a winter or spring annual, germinating mainly in the autumn, and flowering from June to October. Its habitats are mainly arable fields, tracks and path sides, open sandy ground, sand pits and commons or heathland usually in Thero-Airetalia vegetation. It has been recorded in a total of at least 212 sites in 86 10-km squares in south-eastern England, but has been seen in only 14 sites in ten 10-km squares since 1990. It appears to have declined in arable field habitats owing to changes in agricultural practices, and in tracks and heath land owing to reduced disturbance. Much of the decline took place before the 1960s. Population counts for all extant sites between 1993 and 1996 show marked variation from year to year and marked differences between sites. The best conservation management is currently thought to be annual disturbance by digging or rotavation in early autumn. This species is still under severe threat in Britain; only two extant sites have statutory protection and the two largest populations are unprotected. KEYWORDS: population size, ecology, distribution, habitat management, rare species. INTRODUCTION Filago lutescens Jordan (F. apiculata G. E. Srn. ex Bab.; Asteraceae), Red-tipped cudweed, is a rare species in Britain. -

Appendixes, Environmental Assessment, Flint Hills Legacy

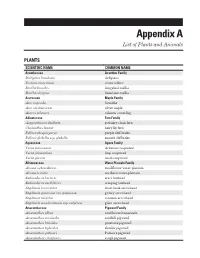

Appendix A List of Plants and Animals PLANTS SCIENTIFIC NAME COMMON NAME Acanthaceae Acanthus Family Dicliptera brachiata dicliptera Justicia americana water willow Ruellia humilis fringeleaf ruellia Ruellia strepens limestone ruellia Aceraceae Maple Family Acer negundo boxelder Acer saccharinum silver maple Acorus calamus calamus sweetflag Adiantaceae Fern Family Argyrochosma dealbata powdery cloak fern Cheilanthes lanosa hairy lip fern Pellaea atropurpurea purple cliff-brake Pellaea glabella ssp. glabella smooth cliffbrake Agavaceae Agave Family Yucca arkansana Arkansas soapweed Yucca filamentosa limp soapweed Yucca glauca small soapweed Alismataceae Water Plantain Family Alisma subcordatum smallflower water plantain Alisma triviale northern water-plantain Echinodorus berteroi erect burhead Echinodorus cordifolius creeping burhead Sagittaria brevirostra short-beak arrowhead Sagittaria graminea var. graminea grassy arrowhead Sagittaria latifolia common arrowhead Sagittaria montevidensis ssp. calycina giant arrowhead Amaranthaceae Pigweed Family Amaranthus albus tumbleweed amaranth Amaranthus arenicola sandhill pigweed Amaranthus blitoides prostrate pigweed Amaranthus hybridus slender pigweed Amaranthus palmeri Palmer’s pigweed Amaranthus retroflexus rough pigweed 36 EA, Flint Hills Legacy Conservation Area, KS SCIENTIFIC NAME COMMON NAME Amaranthus rudis water hemp Amaranthus tuberculatus tall water-hemp Froelichia gracilis slender snakecotton Iresine rhizomatosa bloodleaf Anacardiaceae Sumac Family Rhus aromatica fragrant sumac Rhus -

STB117 Common Names of a Selected List of Plants

Technical Bulletin 117 Revised August 1969 [ Common Names of a Selected List of Plants By Kling l. Anderson and Clanton E. Owensby I [ AGRICULTURAL EXPERIMENT STAnON Kansas State University of Agriculture and Applied Science Manhattan Floyd W. Smith, Director Common Names of a Selected List of Plants' Kling L. Anderson an'd Clanton E. Owensby' Common names of plants often vary widely from place to place, even within rather limited areas. Frequently-occurring and widely-known species may have local names, or the same name may be used for several species. Common names, there fore, often fail to identify plants accurately. That makes it difficult to communicate about plants; the confusion may even discontinue attempts to convey ideas about the subject. Con versations may shift to a subject with an adequate common nomenclature. CONTENTS Scientific names are essential in formal writing. When com mon names are to be used, as in less formal publications, scien Page tific names must also be given either at the place where the Index to common names ............................................................................ 4 common ones first appear in the paper, in a footnote, or in an appended list. Only scientific names identify the species for all Grasses ........................................................................................................ 18 readers. In completely informal writing for a broad area, scientific names may be omitted. Sedges, rushes, and related genera .......................................................... 27 Since common names are so widely used, they should be used as uniformly as possible. The following common names Ferns and related genera .....................: .................................................... 28 are considered "standardized" for all writing in the Kansas Agricultural Experiment Station and may also be used as a Other monocots .........................................................................................