The Contribution of Interspecific Variation in Maximum Tree Height To

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Iden Tification G Uidelines for Endangered Ecolo Gical C

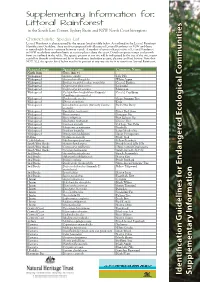

Supplementary Information for: Littoral Rainforest in the South East Corner, Sydney Basin and NSW North Coast bioregions Characteristic Species List Littoral Rainforest is characterised by the species listed in table below. As outlined in the Littoral Rainforest Identification Guideline, there are five recognised sub-alliances of Littoral Rainforest in NSW and there is considerable floristic variation between stands. A number of species characteristic of Littoral Rainforest in NSW reach their southern limits at various places along the coast. Details on species range and growth form are outlined in the table. The species present at any site will be influenced by the size of the site, recent rainfall or drought conditions and by its disturbance (including grazing, clearing and fire) history. Note that NOT ALL the species listed below need to be present at any one site for it to constitute Littoral Rainforest. General range Species name Common Name North from Trees (6m +) Widespread Acmena smithii Lilly Pilly Widespread Acronychia oblongifolia White Aspen Widespread Banksia integrifolia subsp. integrifolia Coastal Banksia Widespread Cryptocarya glaucescens Jackwood Widespread Cryptocarya microneura Murrogun Widespread Cyclophyllum longipetalum (formerly Coastal Canthium Canthium coprosmoides) Widespread Dendrocnide excelsa Giant Stinging Tree Widespread Ehretia acuminata Koda Widespread Elaeodendron australe (formerly Cassine Red Olive Berry australis) Widespread Eucalyptus tereticornis Forest Red Gum Widespread Ficus coronata Sanpaper Fig -

OBSERVATIONS on the DIET of the TOPKNOT PIGEON Lopholaimus Antarcticus in the ILLAWARRA RAINFOREST, NEW SOUTH WALES

OSEAIOS O E IE O E OKO IGEO phl I E IAWAA AIOES EW SOU WAES ntrt , R. D. WATERHOUSE 4/1-5 Ada Street, Oatley, New South Wales 2223 vd: 2 Otbr Obrvtn r d n th fdn bhvr f pnt n Lopholaimus antarcticus fr Mrh 88 t br 2 nr Mt Kr, Wllnn, Sth Wl. h p f plnt tht ntrbtd frt t th dt r rrdd fr h nth f th r. h nlt, ntt nd drtn f frtn b fd p vrd ndrbl vr th td prd. pnt n r fnd t n th frt f rnfrt p nd th tht ntrbtd t t th prn f th brd n th td r r th Cbb r l vtn trl, Mrtn rphll, rn h nnnt nnnh, d Crptr ln, Wht Chrr Shzr vt, pprvn pr nvhllnd nd llpll An th. h r rndd fr rnfrt rvttn h n th Wllnn r. INTRODUCTION 3. to identify 'key' species that could supplement the natural food supplies available locally to Topknot The Topknot Pigeon Lopholaimus antarcticus is a Pigeons as well as other rainforest birds. monotypic Australian endemic which formerly ranged in large flocks, mainly in rainforests along the east coast and Topknot Pigeons were formerly very wary in the region tablelands from Cape York to southern New South Wales due to being hunted extensively until the 1930s. Even (Morris et al. 1981; Pizzey and Knight 1997). today, some illegal shooting takes place in the Illawarra district (D. Rosso, pers. comm.) but no longer occurs in Although at one time reported in flocks of three to five the vicinity of the Mount Keira Scout Camp (D. -

I Is the Sunda-Sahul Floristic Exchange Ongoing?

Is the Sunda-Sahul floristic exchange ongoing? A study of distributions, functional traits, climate and landscape genomics to investigate the invasion in Australian rainforests By Jia-Yee Samantha Yap Bachelor of Biotechnology Hons. A thesis submitted for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy at The University of Queensland in 2018 Queensland Alliance for Agriculture and Food Innovation i Abstract Australian rainforests are of mixed biogeographical histories, resulting from the collision between Sahul (Australia) and Sunda shelves that led to extensive immigration of rainforest lineages with Sunda ancestry to Australia. Although comprehensive fossil records and molecular phylogenies distinguish between the Sunda and Sahul floristic elements, species distributions, functional traits or landscape dynamics have not been used to distinguish between the two elements in the Australian rainforest flora. The overall aim of this study was to investigate both Sunda and Sahul components in the Australian rainforest flora by (1) exploring their continental-wide distributional patterns and observing how functional characteristics and environmental preferences determine these patterns, (2) investigating continental-wide genomic diversities and distances of multiple species and measuring local species accumulation rates across multiple sites to observe whether past biotic exchange left detectable and consistent patterns in the rainforest flora, (3) coupling genomic data and species distribution models of lineages of known Sunda and Sahul ancestry to examine landscape-level dynamics and habitat preferences to relate to the impact of historical processes. First, the continental distributions of rainforest woody representatives that could be ascribed to Sahul (795 species) and Sunda origins (604 species) and their dispersal and persistence characteristics and key functional characteristics (leaf size, fruit size, wood density and maximum height at maturity) of were compared. -

Budawangia* an E-Newsletter for All Those Interested in the Native Plants of the Nsw South Coast

BUDAWANGIA* AN E-NEWSLETTER FOR ALL THOSE INTERESTED IN THE NATIVE PLANTS OF THE NSW SOUTH COAST Contact: Dr Kevin Mills – [email protected] No. 32 - November 2014 Aims: To connect those interested in the native flora of the NSW South Coast, to share up to date information on the flora of the region and to broaden the appreciation of the region’s native plants. Editorial There are so many rainforest trees that many people find it difficult to accurately identify individual species based on leaves alone. This is true of the trees in the laurel family (Lauraceae). This edition contains a piece on identifying the local species based on leaf characteristics. Also included, is a note on a new record of a small rainforest tree found at Minnamurra Rainforest. This edition includes a new mystery weed, a piece on the Giant Pepper Vine of the local rainforests and wetland plant No. 8. Once again, the Illawarra Flame Trees Brachychiton acerifolius are flowering well in the region. Blotches of red appeared along the escarpment and in the rainforest remnants around Kiama early in the month. The common name flame tree is well deserved, as the bright red colour of thousands of flowers really does look like a tree in flame; this is heightened by the fact that the trees are usually leafless at this time. The genus Brachychiton is derived from brachys for short and chiton, a coat of mail, in allusion to the bristly coasting around the seeds in this genus. The species name acerifolius is in reference to the leaves that at times look like those in the deciduous maple tree genus Acer. -

Conservation Area Values Report for 'Belltrees'

CONSERVATION AREA VALUES REPORT FOR ’BELLTREES’ Conservation Area Values Report for ‘Belltrees’ 404 Mudford’s Lane, Landsdowne Protection of Lowland Rainforest and habitat for threatened species including the Spotted-tailed Quoll and Brush-tailed Phascogale Signed and Dated by Landowner recognizing values Report Prepared by BCT Senior Ecologist, Joel Stibbard Page 1 of 35 Belltrees Conservation Area Initials_____________ Contents 1. Introduction .................................................................................................................................... 2 2. Conservation Area ........................................................................................................................... 2 3. Natural Assets of ‘Belltrees’ Conservation Area ............................................................................. 4 4. Vegetation and Priority Species Map .............................................................................................. 8 5. Connectivity Map ............................................................................................................................ 9 6. Weeds ........................................................................................................................................... 10 7. Pest Animals .................................................................................................................................. 11 8. Species Lists ................................................................................................................................. -

Fleshy Fruitsareproducedbymanyplants, What Arefleshyfruits? Has Beenseverelyreduced Since European the Distributionofrainforest Innsw New Rainforestspecies

Fleshy Fruits Food trees for Wildlife 5 What are Fleshy Fruits? settlement with for example less than 1% of lowland sub-tropical rainforest remaining. Fleshy fruits are produced by many plants, Outside of national parks, rainforest NOTE and in particular rainforest species, to occurs now only as small areas, isolated enclose the seed for reproduction of the remnants or as single trees in an agricultural plant. They comprise a fleshy outer layer landscape. As a consequence of this severe within a leathery skin and a central hard reduction in extent and distribution of stone enclosing the seed. rainforest there has been a marked decline DECC in the abundance of a number of pigeons, doves and parrots and other animals reliant on rainforests. Consequently many of these species are now considered rare and threatened in NSW. What can you do? The protection of vegetation including remnants and isolated paddock trees (e.g. figs) that annually produce fleshy fruit, is Assortment of Fleshy Fruits very significant in ensuring the continued survival of many threatened birds and Why are they mammals such as migratory bird and flying- important? fox species. Fleshy fruits vary considerably in size and Forestry operations are not permitted within texture making them an attractive and key rainforests although existing roads can be food resource for many species of native maintained. birds, particularly pigeons (many of which Table 1 lists some of the fleshy fruited feed almost exclusively on fleshy fruits), and rainforest species occurring on the north a number of mammals such as possum and coast. These species can occur in rainforest small rodents. -

Plants of Magnetic Island

PLANTS OF MAGNETIC ISLAND 3rd EDITION BETSY R. JACKES SCHOOL OF MARINE and TROPICAL BIOLOGY JAMES COOK UNIVERSITY TOWNSVILLE QUEENSLAND 1 © James Cook University 2010 Jackes Betsy R (Betsy Rivers) Plants of Magnetic Island ISBN: 978-0-9808183-8-3 ACKNOWLEDGMENTS This publication is based on "Plants of Magnetic Island', Editions 1 (1987) and 2 (2003). To all those who have collected plants for the 1987 edition and subsequently my sincere thanks. Art work is by Ashley Field, Geoff Kelly and Norm Duke, with small sketches by myself. Other illustrations are based on photocopies and recently coloured scans of actual plants. Photographs of flowers chiefly by Andi Cairns, John Elliott, Chris Gardiner, Don Kinsey and Andrea Lim. The map was prepared by Adella Edwards, Cartography, James Cook University, modified from Sandercoe (1990) with permission of the Director, Queensland Herbarium. Andi Cairns provided valuable assistance with the layout and with suggestions on the manuscript. To all those who have suggested changes, who have provided lists of plants, particularly the staff of the Queensland Herbarium, my grateful thanks. Names updated 2021. 2 GUIDE TO THE PLANTS OF MAGNETIC ISLAND MANGROVES, DUNES AND WOODLANDS Betsy R. Jackes Magnetic Island (190 08 S, 1480 50 E), offshore from the north Queensland city of Townsville, was first named by Captain James Cook in 1770. He called it “Magnetical Point, land which has the appearance of an island”, because his compass moved erratically as he passed it. This large island, about 5,000 ha in area, rises to 493 m at Mt Cook, the highest point. -

Triunia Environmental Reserve Management Plan

Triunia Environmental Reserve Management Plan 2016 - 2026 © Sunshine Coast Council 2009-current. Sunshine Coast Council™ is a registered trademark of Sunshine Coast Council. www.sunshinecoast.qld.gov.au [email protected] T 07 5475 7272 F 07 5475 7277 Locked Bag 72 Sunshine Coast Mail Centre Qld 4560 Acknowledgements Council wishes to thank all contributors and stakeholders involved in the development of this document. Disclaimer Information contained in this document is based on available information at the time of writing. All figures and diagrams are indicative only and should be referred to as such. While the Sunshine Coast Council has exercised reasonable care in preparing this document it does not warrant or represent that it is accurate or complete. Council or its officers accept no responsibility for any loss occasioned to any person acting or refraining from acting in reliance upon any material contained in this document. Contents 1. Executive Summary .............................................................................. 5 2. Acknowledgements ............................................................................ 6 3. Introduction........................................................................................... 7 3.1 Purpose of the Management Plan ................................................... 7 3.2 Management Intent for the reserve .................................................. 7 4. Description of the reserve .................................................................... 7 4.1 -

The Forest Flora of New South Wales Volume 5 Parts 41-50

The Forest Flora of New South Wales Volume 5 Parts 41-50 Maiden, J. H. (Joseph Henry) University of Sydney Library Sydney, Australia 1999 http://setis.library.usyd.edu.au/badham © University of Sydney Library. The texts and images are not to be used for commercial purposes without permission. Illustrations have been included from the print version. Source Text: Prepared from the print edition published by the Forest Department of New South Wales Sydney 1913 J.H.Maiden, Government Botanist of New South Wales and Director of the Botanic Gardens, Sydney. Volume 5 includes Parts 41 to 50. All quotation marks retained as data. All unambiguous end-of-line hyphens have been removed, and the trailing part of a word has been joined to the preceding line. Images exist as archived TIFF images, one or more JPG and GIF images for general use. Australian Etexts botany natural history 1910-1939 23rd November 1999 Final Checking and Parsing Forest Flora of New South Wales Volume 5: Parts XLI-L Sydney William Applegate Gullick, Government Printer 1913. Part XLI. Joseph Henry Maiden The Forest Flora of New South Wales Part XLI Sydney William Applegate Gullick, Government Printer 1910 Published by the Forest Department of New South Wales, under authority of the Honourable the Secretary for Lands. Price, 1/- per Part, or 10/- per dozen Parts, payable in advance. No. 147: Banksia Paludosa, R.Br. A Honeysuckle. (Family PROTEACEÆ.) Botanical description. — Genus, Banksia. (See Part VIII, p. 169.) Botanical description. — Species, B. paludosa, R.Br. Robert Brown, in his Prod. No. 394, has the following description:— "B. -

Bartopia & Environs – Flora Species List

Bartopia & Environs – Flora Species List - March 2005 This list currently comprises at 01Mar05 - 513 species of plants in 113 plant families. Note: environs includes approximately one kilometer beyond the property perimeter to allow for seed dispersal and habitat shifts due to climate, fire, etc. FLORA Culcitaceae PTERIDOPHYTA Calochlaena dubia Soft Bracken Fern Adiantaceae Adiantum aethiopicum Maidenhair Fern Cyatheaceae Adiantum diaphanum Filmy Maidenhair Fern Cyathea australis Rough Tree Fern Adiantum formosum Giant Maidenhair Fern/ Black Stem Cyathea cooperii Common Tree Fern Fern Adiantum hispidulum Rough Maidenhair Fern Davalliaceae Cheilanthes distans Davallia solida var. pyxidata Hares Foot Fern Cheilanthes sieberii Pellaea falcata Sickle Fern Pellaea paradoxa Dennsteadtiaceae Dennsteadtia davallioides Soft Shield Fern Hypolepis glandulifera Aspleniaceae Hypolepis meullerii Asplenium attenuatum var. attenuatum Walking Fern Asplenium australasicum Crows Nest Fern Asplenium flabellifolium Necklace Fern Drypoteridaceae Asplenium polyodon Mares Tail Fern Arachniodes aristata Prickly Shield Fern Lastreopsis decomposita Lastreopsis microsora Blechnaceae Lastreospsis munita Blechnum cartilagineum Gristle Fern Lastreopsis shepherdii Creeping Shield Fern Blechnum cartilagineum X Doodia aspera (Intergeneric Hybrid) Polystichum fallax Doodia aspera Rasp Fern Doodia australis Grammitidaceae Doodia caudata Small Rasp Fern Grammitis billardierei Finger Fern Doodia linearis Doodia media Soft Rasp Fern Hymenophyllaceae Hymenophyllum bivalve A -

Dynamics of Tree Diversity in Undisturbed and Logged Subtropical Rainforest in Australia

Preprint of: Biodiversity and Conservation (2005) 14:2447–2463 DOI 10.1007/s10531-004-0215-0 Dynamics of tree diversity in undisturbed and logged subtropical rainforest in Australia R. Geoff B. Smith 1 (corresponding author) J. Doland Nichols 2 Jerome K. Vanclay 2 1. State Forests of New South Wales Research and Development Division. Coffs Harbour, NSW 2450 Australia [email protected] 2. Forestry Program, Environmental Science and Management, Southern Cross University, Lismore, NSW 2480 Australia [email protected] telephone 612 6620 3492 Fax 612 6621 2669 Abstract In subtropical rainforest in eastern Australia, changes in the diversity of trees were compared under natural conditions and eight silvicultural regimes over 35 years. In the treated plots basal area remaining after logging ranged from 12 to 58 m 2 per ha. In three control plots richness differed little over this period. In the eight treated plots richness per plot generally declined after intervention and then gradually increased to greater than original diversity. After logging there was a reduction in richness per plot and an increase in species richness per stem in all but the lightest selective treatments. The change in species diversity was related to the intensity of the logging, however the time taken for species richness to return to pre-logging levels was similar in all silvicultural treatments and was not effected by the intensity of treatment. These results suggest that light selective logging in these forests mainly affects dominant species. The return to high diversity after only a short time under all silvicultural regimes suggests that sustainability and the manipulation of species composition for desired management outcomes is possible. -

The International Timber Trade

THE INTERNATIONAL TIMBER TRADE: A Working List of Commercial Timber Tree Species By Jennifer Mark1, Adrian C. Newton1, Sara Oldfield2 and Malin Rivers2 1 Faculty of Science & Technology, Bournemouth University 2 Botanic Gardens Conservation International The International Timber Trade: A working list of commercial timber tree species By Jennifer Mark, Adrian C. Newton, Sara Oldfield and Malin Rivers November 2014 Published by Botanic Gardens Conservation International Descanso House, 199 Kew Road, Richmond, TW9 3BW, UK Cover Image: Sapele sawn timber being put together at IFO in the Republic of Congo. Photo credit: Danzer Group. 1 Table of Contents Introduction ............................................................................................................ 3 Summary ................................................................................................................. 4 Purpose ................................................................................................................ 4 Aims ..................................................................................................................... 4 Considerations for using the Working List .......................................................... 5 Section Guide ...................................................................................................... 6 Section 1: Methods and Rationale .......................................................................... 7 Rationale - Which tree species are internationally traded for timber? .............