Rainforests of the Illawarra

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Mt Keira Summit Park PLAN of MANAGEMENT December 2019

Mt Keira Summit Park PLAN OF MANAGEMENT December 2019 The Mt Keira Summit Park Plan of Management was prepared by TRC Tourism Pty Ltd for Wollongong City Council. Acknowledgements Images used in this Plan are courtesy of Wollongong City Council, Destination Wollongong and TRC Tourism except where otherwise indicated. Acknowledgement of Country Disclaimer Wollongong City Council would like to show their Any representation, statement, opinion or advice, respect and acknowledge the traditional expressed or implied in this document is made in good custodians of the Land, of Elders past and present, faith but on the basis that TRC Tourism Pty. Ltd., and extend that respect to other Aboriginal and directors, employees and associated entities are not Torres Strait Islander people. liable for any damage or loss whatsoever which has occurred or may occur in relation to taking or not taking action in respect of any representation, statement or advice referred to in this document. ©Copyright TRC Tourism Pty Ltd www.trctourism.com Contents 1 Introduction .......................................................................................................................................... 1 1.1 Background ................................................................................................................................... 1 1.2 Purpose of the Plan of Management ............................................................................................ 2 1.3 Making of the Plan of Management ............................................................................................ -

NPWS Pocket Guide 3E (South Coast)

SOUTH COAST 60 – South Coast Murramurang National Park. Photo: D Finnegan/OEH South Coast – 61 PARK LOCATIONS 142 140 144 WOLLONGONG 147 132 125 133 157 129 NOWRA 146 151 145 136 135 CANBERRA 156 131 148 ACT 128 153 154 134 137 BATEMANS BAY 139 141 COOMA 150 143 159 127 149 130 158 SYDNEY EDEN 113840 126 NORTH 152 Please note: This map should be used as VIC a basic guide and is not guaranteed to be 155 free from error or omission. 62 – South Coast 125 Barren Grounds Nature Reserve 145 Jerrawangala National Park 126 Ben Boyd National Park 146 Jervis Bay National Park 127 Biamanga National Park 147 Macquarie Pass National Park 128 Bimberamala National Park 148 Meroo National Park 129 Bomaderry Creek Regional Park 149 Mimosa Rocks National Park 130 Bournda National Park 150 Montague Island Nature Reserve 131 Budawang National Park 151 Morton National Park 132 Budderoo National Park 152 Mount Imlay National Park 133 Cambewarra Range Nature Reserve 153 Murramarang Aboriginal Area 134 Clyde River National Park 154 Murramarang National Park 135 Conjola National Park 155 Nadgee Nature Reserve 136 Corramy Regional Park 156 Narrawallee Creek Nature Reserve 137 Cullendulla Creek Nature Reserve 157 Seven Mile Beach National Park 138 Davidson Whaling Station Historic Site 158 South East Forests National Park 139 Deua National Park 159 Wadbilliga National Park 140 Dharawal National Park 141 Eurobodalla National Park 142 Garawarra State Conservation Area 143 Gulaga National Park 144 Illawarra Escarpment State Conservation Area Murramarang National Park. Photo: D Finnegan/OEH South Coast – 63 BARREN GROUNDS BIAMANGA NATIONAL PARK NATURE RESERVE 13,692ha 2,090ha Mumbulla Mountain, at the upper reaches of the Murrah River, is sacred to the Yuin people. -

Brass Bands of the World a Historical Directory

Brass Bands of the World a historical directory Kurow Haka Brass Band, New Zealand, 1901 Gavin Holman January 2019 Introduction Contents Introduction ........................................................................................................................ 6 Angola................................................................................................................................ 12 Australia – Australian Capital Territory ......................................................................... 13 Australia – New South Wales .......................................................................................... 14 Australia – Northern Territory ....................................................................................... 42 Australia – Queensland ................................................................................................... 43 Australia – South Australia ............................................................................................. 58 Australia – Tasmania ....................................................................................................... 68 Australia – Victoria .......................................................................................................... 73 Australia – Western Australia ....................................................................................... 101 Australia – other ............................................................................................................. 105 Austria ............................................................................................................................ -

Guide to Cycling in the Illawarra

The Illawarra Bicycle Users Group’s Guide to cycling in the Illawarra Compiled by Werner Steyer First edition September 2006 4th revision August 2011 Copyright Notice: © W. Steyer 2010 You are welcome to reproduce the material that appears in the Tour De Illawarra cycling guide for personal, in-house or non-commercial use without formal permission or charge. All other rights are reserved. If you wish to reproduce, alter, store or transmit material appearing in the Tour De Illawarra cycling guide for any other purpose, request for formal permission should be directed to W. Steyer 68 Lake Entrance Road Oak Flats NSW 2529 Introduction This cycling ride guide and associated maps have been produced by the Illawarra Bicycle Users Group incorporated (iBUG) to promote cycling in the Illawarra. The ride guides and associated maps are intended to assist cyclists in planning self- guided outings in the Illawarra area. All persons using this guide accept sole responsibility for any losses or injuries uncured as a result of misinterpretations or errors within this guide Cyclist and users of this Guide are responsible for their own actions and no warranty or liability is implied. Should you require any further information, find any errors or have suggestions for additional rides please contact us at www.ibug,org.com Updated ride information is available form the iBUG website at www.ibug.org.au As the conditions may change due to road and cycleway alteration by Councils and the RTA and weather conditions cyclists must be prepared to change their plans and riding style to suit the conditions encountered. -

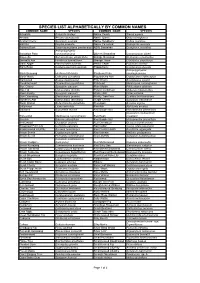

Species List Alphabetically by Common Names

SPECIES LIST ALPHABETICALLY BY COMMON NAMES COMMON NAME SPECIES COMMON NAME SPECIES Actephila Actephila lindleyi Native Peach Trema aspera Ancana Ancana stenopetala Native Quince Guioa semiglauca Austral Cherry Syzygium australe Native Raspberry Rubus rosifolius Ball Nut Floydia praealta Native Tamarind Diploglottis australis Banana Bush Tabernaemontana pandacaqui NSW Sassafras Doryphora sassafras Archontophoenix Bangalow Palm cunninghamiana Oliver's Sassafras Cinnamomum oliveri Bauerella Sarcomelicope simplicifolia Orange Boxwood Denhamia celastroides Bennetts Ash Flindersia bennettiana Orange Thorn Citriobatus pauciflorus Black Apple Planchonella australis Pencil Cedar Polyscias murrayi Black Bean Castanospermum australe Pepperberry Cryptocarya obovata Archontophoenix Black Booyong Heritiera trifoliolata Picabeen Palm cunninghamiana Black Wattle Callicoma serratifolia Pigeonberry Ash Cryptocarya erythroxylon Blackwood Acacia melanoxylon Pink Cherry Austrobuxus swainii Bleeding Heart Omalanthus populifolius Pinkheart Medicosma cunninghamii Blue Cherry Syzygium oleosum Plum Myrtle Pilidiostigma glabrum Blue Fig Elaeocarpus grandis Poison Corkwood Duboisia myoporoides Blue Lillypilly Syzygium oleosum Prickly Ash Orites excelsa Blue Quandong Elaeocarpus grandis Prickly Tree Fern Cyathea leichhardtiana Blueberry Ash Elaeocarpus reticulatus Purple Cherry Syzygium crebrinerve Blush Walnut Beilschmiedia obtusifolia Red Apple Acmena ingens Bollywood Litsea reticulata Red Ash Alphitonia excelsa Bolwarra Eupomatia laurina Red Bauple Nut Hicksbeachia -

Iden Tification G Uidelines for Endangered Ecolo Gical C

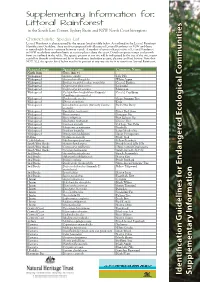

Supplementary Information for: Littoral Rainforest in the South East Corner, Sydney Basin and NSW North Coast bioregions Characteristic Species List Littoral Rainforest is characterised by the species listed in table below. As outlined in the Littoral Rainforest Identification Guideline, there are five recognised sub-alliances of Littoral Rainforest in NSW and there is considerable floristic variation between stands. A number of species characteristic of Littoral Rainforest in NSW reach their southern limits at various places along the coast. Details on species range and growth form are outlined in the table. The species present at any site will be influenced by the size of the site, recent rainfall or drought conditions and by its disturbance (including grazing, clearing and fire) history. Note that NOT ALL the species listed below need to be present at any one site for it to constitute Littoral Rainforest. General range Species name Common Name North from Trees (6m +) Widespread Acmena smithii Lilly Pilly Widespread Acronychia oblongifolia White Aspen Widespread Banksia integrifolia subsp. integrifolia Coastal Banksia Widespread Cryptocarya glaucescens Jackwood Widespread Cryptocarya microneura Murrogun Widespread Cyclophyllum longipetalum (formerly Coastal Canthium Canthium coprosmoides) Widespread Dendrocnide excelsa Giant Stinging Tree Widespread Ehretia acuminata Koda Widespread Elaeodendron australe (formerly Cassine Red Olive Berry australis) Widespread Eucalyptus tereticornis Forest Red Gum Widespread Ficus coronata Sanpaper Fig -

A Brief History of the Mount Keira Tramline

84 NOV /DEC 2000 lllawarra Historical Society Inc. A BRIEF HISTORY OF THE MOUNT KEIRA TRAMLINE 1839 The Rev W B Clarke, who was a qualified geologist, recorded a finding of coal at Mount Keira. 1848 James Shoobert, a retired sea captain and land-owner, drove a tunnel in what is now known as the No. 3 seam. He then observed an outcrop of the No. 2 (4-ft) seam about 21 metres above it, in which the coal was of better quality. 1849 Shoobert then opened a tunnel in the 4-ft seam, which seems to have been on the north side of Para Creek. A track was then cut through the bush to the Mount Keira Road where a depot was established about 400 metres west of the crossroads forming the junction with the main south road. The track and the crossroads both appear on Plan A (page 85), an 1855 proposal to supply Wollongong with water. The first load of coal was taken from this depot to Wollongong Harbour, with much fanfare, on August 27. The coal was delivered from the mine to the depot by bullock drays and dumped there. It was then loaded onto horse-drawn drays and taken to the harbour, where it was bagged and carried on board the waiting vessel, the paddle steamer William the Fourth, and tipped into its hold. [Sydney Morning Herald 10.09.1849) Plan B (page 87) is a line diagram showing the position ofShoobert's road in relation to later developments. 1850 A second tunnel was opened in the 4-ft seam. -

Two Centuries of Botanical Exploration Along the Botanists Way, Northern Blue Mountains, N.S.W: a Regional Botanical History That Refl Ects National Trends

Two Centuries of Botanical Exploration along the Botanists Way, Northern Blue Mountains, N.S.W: a Regional Botanical History that Refl ects National Trends DOUG BENSON Honorary Research Associate, National Herbarium of New South Wales, Royal Botanic Gardens and Domain Trust, Sydney NSW 2000, AUSTRALIA. [email protected] Published on 10 April 2019 at https://openjournals.library.sydney.edu.au/index.php/LIN/index Benson, D. (2019). Two centuries of botanical exploration along the Botanists Way, northern Blue Mountains,N.S.W: a regional botanical history that refl ects national trends. Proceedings of the Linnean Society of New South Wales 141, 1-24. The Botanists Way is a promotional concept developed by the Blue Mountains Botanic Garden at Mt Tomah for interpretation displays associated with the adjacent Greater Blue Mountains World Heritage Area (GBMWHA). It is based on 19th century botanical exploration of areas between Kurrajong and Bell, northwest of Sydney, generally associated with Bells Line of Road, and focussed particularly on the botanists George Caley and Allan Cunningham and their connections with Mt Tomah. Based on a broader assessment of the area’s botanical history, the concept is here expanded to cover the route from Richmond to Lithgow (about 80 km) including both Bells Line of Road and Chifl ey Road, and extending north to the Newnes Plateau. The historical attraction of botanists and collectors to the area is explored chronologically from 1804 up to the present, and themes suitable for visitor education are recognised. Though the Botanists Way is focused on a relatively limited geographic area, the general sequence of scientifi c activities described - initial exploratory collecting; 19th century Gentlemen Naturalists (and lady illustrators); learned societies and publications; 20th century publicly-supported research institutions and the beginnings of ecology, and since the 1960s, professional conservation research and management - were also happening nationally elsewhere. -

Reconstructing the Basal Angiosperm Phylogeny: Evaluating Information Content of Mitochondrial Genes

55 (4) • November 2006: 837–856 Qiu & al. • Basal angiosperm phylogeny Reconstructing the basal angiosperm phylogeny: evaluating information content of mitochondrial genes Yin-Long Qiu1, Libo Li, Tory A. Hendry, Ruiqi Li, David W. Taylor, Michael J. Issa, Alexander J. Ronen, Mona L. Vekaria & Adam M. White 1Department of Ecology & Evolutionary Biology, The University Herbarium, University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, Michigan 48109-1048, U.S.A. [email protected] (author for correspondence). Three mitochondrial (atp1, matR, nad5), four chloroplast (atpB, matK, rbcL, rpoC2), and one nuclear (18S) genes from 162 seed plants, representing all major lineages of gymnosperms and angiosperms, were analyzed together in a supermatrix or in various partitions using likelihood and parsimony methods. The results show that Amborella + Nymphaeales together constitute the first diverging lineage of angiosperms, and that the topology of Amborella alone being sister to all other angiosperms likely represents a local long branch attrac- tion artifact. The monophyly of magnoliids, as well as sister relationships between Magnoliales and Laurales, and between Canellales and Piperales, are all strongly supported. The sister relationship to eudicots of Ceratophyllum is not strongly supported by this study; instead a placement of the genus with Chloranthaceae receives moderate support in the mitochondrial gene analyses. Relationships among magnoliids, monocots, and eudicots remain unresolved. Direct comparisons of analytic results from several data partitions with or without RNA editing sites show that in multigene analyses, RNA editing has no effect on well supported rela- tionships, but minor effect on weakly supported ones. Finally, comparisons of results from separate analyses of mitochondrial and chloroplast genes demonstrate that mitochondrial genes, with overall slower rates of sub- stitution than chloroplast genes, are informative phylogenetic markers, and are particularly suitable for resolv- ing deep relationships. -

Coke Making in the Illawarra : a Talk Given by Don Reynolds

COKE MAKING IN ILLA WARRA A talk given by Don Reynolds to the Society in March 2006. Coke making began in Illawarra in 1874 by Osborne and Ahearn who built a small battery of circular beehive coke ovens on a site just to the south of Wollongong Harbour, that undertalcing only lasted till about 1890. In 1984 the site was exposed by council when carrying out road works just south east of Belmore Basin; the site was examined and recorded by Brian Rogers and then filled in. In 1884 Thomas Bertram opened the Broker's Nose Coal Company in the escarpment behind what is now CorrimaJ; he built a set of 7 beehive coke ovens (presumably of the circular type) on the northern side of Tarrawanna Road, it appears that these ovens only operated spasmodically. The Southern Coal Company (SCC) was formed in the UK to build a coJliery on the southern slopes ofMt Kembla and a railway from the mine to a jetty they were building in an unprotected bay at Five Islands. They also built a large set of modem rectangular beehive coke ovens alongside their railway near where the Commonwealth Steel stainless steel plant was much later built. This coke ovens plant, which was known as the Australian Coke Making Company, went into service in 1888. The coal mine of the SCC immediately ran into problems due to geological disturbances and the mine was abandoned. They negotiated with Thomas Bertram and leased his Corrimal coal mining and railway facilities in order to meet their commitments. The SCC quickly upgraded the Corrimal facility and began to rail coal to their new jetty and coke works. -

Fauna Survey, Wingham Management Area, Port Macquarie Region

This document has been scanned from hard-copy archives for research and study purposes. Please note not all information may be current. We have tried, in preparing this copy, to make the content accessible to the widest possible audience but in some cases we recognise that the automatic text recognition maybe inadequate and we apologise in advance for any inconvenience this may cause. FOREST RESOURCES SERIES NO. 19 FAUNA SURVEY, WINGHAM MANAGEMENT AREA, PORT MACQUARIE REGION PART 1. MAMMALS BY ALAN YORK \ \ FORESTRY COMMISSION OF NEW SOUTH WALES ----------------------------- FAUNA SURVEY, WINGHAM MANAGEMENT AREA, PORT MACQUARIE REGION PART 1. MAMMALS by ALAN YORK FOREST ECOLOGY SECTION WOOD TECHNOLOGY AND FOREST RESEARCH DIVISION FORESTRY COMMISSION OF NEW SOUTH WALES SYDNEY 1992 Forest Resources Series No. 19 March 1992 The Author: AIan York, BSc.(Hons.) PhD., Wildlife Ecologist, Forest Ecology Section, Wood Technology and Forest Research Division, Forestry Commission ofNew South Wales. Published by: Forestry Commission ofNew South Wales, Wood Technology and Forest Research Division, 27 Oratava Avenue, West Pennant Hills, 2125 P.O. Box lOO, Beecroft 2119 Australia. Copyright © 1992 by Forestry Commission ofNew South Wales ODC 156.2:149 (944) ISSN 1033-1220 ISBN 07305 5663 8 Fauna Survey, Wingham Management Area, -i- PortMacquarie Region Part 1. Mammals TABLE OF CONTENTS PAGE INTRODUCTION 1 1. The Wingham Management Area 1 (a) Location 1 (b) Physical environment 3 (c) Vegetation communities 3 (d) Fire 5 (e) Timber harvesting : 5 SURVEY METHODOLOGy 7 1. Overall Sampling Strategy 7 (a) General survey 7 (b) Plot-based survey 7 (i) Stratification 1:Jy Broad Forest Type : 8 (ii) Stratification by Altitude 8 (iii) Stratification 1:Jy Management History 8 (iv) Plot selection 9 (v) Special considerations 9 (vi) Plot establishment 10 (vii) Plot design........................................................................................................... -

World Heritage Values and to Identify New Values

FLORISTIC VALUES OF THE TASMANIAN WILDERNESS WORLD HERITAGE AREA J. Balmer, J. Whinam, J. Kelman, J.B. Kirkpatrick & E. Lazarus Nature Conservation Branch Report October 2004 This report was prepared under the direction of the Department of Primary Industries, Water and Environment (World Heritage Area Vegetation Program). Commonwealth Government funds were contributed to the project through the World Heritage Area program. The views and opinions expressed in this report are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect those of the Department of Primary Industries, Water and Environment or those of the Department of the Environment and Heritage. ISSN 1441–0680 Copyright 2003 Crown in right of State of Tasmania Apart from fair dealing for the purposes of private study, research, criticism or review, as permitted under the Copyright Act, no part may be reproduced by any means without permission from the Department of Primary Industries, Water and Environment. Published by Nature Conservation Branch Department of Primary Industries, Water and Environment GPO Box 44 Hobart Tasmania, 7001 Front Cover Photograph: Alpine bolster heath (1050 metres) at Mt Anne. Stunted Nothofagus cunninghamii is shrouded in mist with Richea pandanifolia scattered throughout and Astelia alpina in the foreground. Photograph taken by Grant Dixon Back Cover Photograph: Nothofagus gunnii leaf with fossil imprint in deposits dating from 35-40 million years ago: Photograph taken by Greg Jordan Cite as: Balmer J., Whinam J., Kelman J., Kirkpatrick J.B. & Lazarus E. (2004) A review of the floristic values of the Tasmanian Wilderness World Heritage Area. Nature Conservation Report 2004/3. Department of Primary Industries Water and Environment, Tasmania, Australia T ABLE OF C ONTENTS ACKNOWLEDGMENTS .................................................................................................................................................................................1 1.