Narratives of Home on the Fringe of Tehran: the Case of Shahriar County

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Investigation of Population Establishment Pattern in The

Copyright © 2014 Scienceline Publication Journal of Civil Engineering and Urbanism Volume 4, Issue 4: 390-396 (2014) ISSN-2252-0430 Investigation of Population Establishment Pattern in the Residential Centers of Tehran Metropolitan Area in Relation to the Role of Urban- Regional Management and Planning System (1966-2011) Manijeh Lalepour Assistant Professor, Department of Geography and Urban Planning, University of Maragheh, Maragheh, Iran *Corresponding author’s E-mail: [email protected] ABSTRACT: Current study has analyzed the trend of population establishment in residential centers of Tehran metropolitan area between 1986-2011 in relation to the role of formal management and planning system of the country. Hence, the trend of spatial establishment of population in the region has been considered through population absorption pattern of urban and rural settlements of the region and new towns position. The research method is descriptive-analytical. Results show that the structure of management and ORIGINAL ARTICLE Received 15 Jun. 2014 15 Jun. Received planning of Tehran metropolitan area in the organization of region’s population establishment hasn’t 2014 10 Jul. Accepted solidarity and coordination. Population settlement plans in Tehran metropolitan area which has been implemented in the framework of new towns plan has acted in an abstract space without paying attention to policy making and integrated planning for development of other physical elements such as industrial activity centers, communication network and public services and utilities of metropolitan area has acted. This matter has caused that regardless of considerable capacity making in planned new towns, these centers don’t play important role in organization of population establishment in the region. -

Sand Dune Systems in Iran - Distribution and Activity

Sand Dune Systems in Iran - Distribution and Activity. Wind Regimes, Spatial and Temporal Variations of the Aeolian Sediment Transport in Sistan Plain (East Iran) Dissertation Thesis Submitted for obtaining the degree of Doctor of Natural Science (Dr. rer. nat.) i to the Fachbereich Geographie Philipps-Universität Marburg by M.Sc. Hamidreza Abbasi Marburg, December 2019 Supervisor: Prof. Dr. Christian Opp Physical Geography Faculty of Geography Phillipps-Universität Marburg ii To my wife and my son (Hamoun) iii A picture of the rock painting in the Golpayegan Mountains, my city in Isfahan province of Iran, it is written in the Sassanid Pahlavi line about 2000 years ago: “Preserve three things; water, fire, and soil” Translated by: Prof. Dr. Rasoul Bashash, Photo: Mohammad Naserifard, winter 2004. Declaration by the Author I declared that this thesis is composed of my original work, and contains no material previously published or written by another person except where due reference has been made in the text. I have clearly stated the contribution by others to jointly-authored works that I have included in my thesis. Hamidreza Abbasi iv List of Contents Abstract ................................................................................................................................................. 1 1. General Introduction ........................................................................................................................ 7 1.1 Introduction and justification ........................................................................................................ -

See the Document

IN THE NAME OF GOD IRAN NAMA RAILWAY TOURISM GUIDE OF IRAN List of Content Preamble ....................................................................... 6 History ............................................................................. 7 Tehran Station ................................................................ 8 Tehran - Mashhad Route .............................................. 12 IRAN NRAILWAYAMA TOURISM GUIDE OF IRAN Tehran - Jolfa Route ..................................................... 32 Collection and Edition: Public Relations (RAI) Tourism Content Collection: Abdollah Abbaszadeh Design and Graphics: Reza Hozzar Moghaddam Photos: Siamak Iman Pour, Benyamin Tehran - Bandarabbas Route 48 Khodadadi, Hatef Homaei, Saeed Mahmoodi Aznaveh, javad Najaf ...................................... Alizadeh, Caspian Makak, Ocean Zakarian, Davood Vakilzadeh, Arash Simaei, Abbas Jafari, Mohammadreza Baharnaz, Homayoun Amir yeganeh, Kianush Jafari Producer: Public Relations (RAI) Tehran - Goragn Route 64 Translation: Seyed Ebrahim Fazli Zenooz - ................................................ International Affairs Bureau (RAI) Address: Public Relations, Central Building of Railways, Africa Blvd., Argentina Sq., Tehran- Iran. www.rai.ir Tehran - Shiraz Route................................................... 80 First Edition January 2016 All rights reserved. Tehran - Khorramshahr Route .................................... 96 Tehran - Kerman Route .............................................114 Islamic Republic of Iran The Railways -

Mayors for Peace Member Cities 2021/10/01 平和首長会議 加盟都市リスト

Mayors for Peace Member Cities 2021/10/01 平和首長会議 加盟都市リスト ● Asia 4 Bangladesh 7 China アジア バングラデシュ 中国 1 Afghanistan 9 Khulna 6 Hangzhou アフガニスタン クルナ 杭州(ハンチォウ) 1 Herat 10 Kotwalipara 7 Wuhan ヘラート コタリパラ 武漢(ウハン) 2 Kabul 11 Meherpur 8 Cyprus カブール メヘルプール キプロス 3 Nili 12 Moulvibazar 1 Aglantzia ニリ モウロビバザール アグランツィア 2 Armenia 13 Narayanganj 2 Ammochostos (Famagusta) アルメニア ナラヤンガンジ アモコストス(ファマグスタ) 1 Yerevan 14 Narsingdi 3 Kyrenia エレバン ナールシンジ キレニア 3 Azerbaijan 15 Noapara 4 Kythrea アゼルバイジャン ノアパラ キシレア 1 Agdam 16 Patuakhali 5 Morphou アグダム(県) パトゥアカリ モルフー 2 Fuzuli 17 Rajshahi 9 Georgia フュズリ(県) ラージシャヒ ジョージア 3 Gubadli 18 Rangpur 1 Kutaisi クバドリ(県) ラングプール クタイシ 4 Jabrail Region 19 Swarupkati 2 Tbilisi ジャブライル(県) サルプカティ トビリシ 5 Kalbajar 20 Sylhet 10 India カルバジャル(県) シルヘット インド 6 Khocali 21 Tangail 1 Ahmedabad ホジャリ(県) タンガイル アーメダバード 7 Khojavend 22 Tongi 2 Bhopal ホジャヴェンド(県) トンギ ボパール 8 Lachin 5 Bhutan 3 Chandernagore ラチン(県) ブータン チャンダルナゴール 9 Shusha Region 1 Thimphu 4 Chandigarh シュシャ(県) ティンプー チャンディーガル 10 Zangilan Region 6 Cambodia 5 Chennai ザンギラン(県) カンボジア チェンナイ 4 Bangladesh 1 Ba Phnom 6 Cochin バングラデシュ バプノム コーチ(コーチン) 1 Bera 2 Phnom Penh 7 Delhi ベラ プノンペン デリー 2 Chapai Nawabganj 3 Siem Reap Province 8 Imphal チャパイ・ナワブガンジ シェムリアップ州 インパール 3 Chittagong 7 China 9 Kolkata チッタゴン 中国 コルカタ 4 Comilla 1 Beijing 10 Lucknow コミラ 北京(ペイチン) ラクノウ 5 Cox's Bazar 2 Chengdu 11 Mallappuzhassery コックスバザール 成都(チォントゥ) マラパザーサリー 6 Dhaka 3 Chongqing 12 Meerut ダッカ 重慶(チョンチン) メーラト 7 Gazipur 4 Dalian 13 Mumbai (Bombay) ガジプール 大連(タァリィェン) ムンバイ(旧ボンベイ) 8 Gopalpur 5 Fuzhou 14 Nagpur ゴパルプール 福州(フゥチォウ) ナーグプル 1/108 Pages -

Nutritive Value of Persian Walnut (Juglans Regia L.) Orchards

American-Eurasian J. Agric. & Environ. Sci., 14 (11): 1228-1235, 2014 ISSN 1818-6769 © IDOSI Publications, 2014 DOI: 10.5829/idosi.aejaes.2014.14.11.12438 Nutritive Value of Persian Walnut (Juglans regia L.) Orchards 12Sara Aryapak and Parisa Ziarati 1Department of Food Sciences and Technology, Pharmaceutical Sciences Branch (IAUPS), Islamic Azad University, Tehran, Iran 2Department of Medicinal Chemistry, Pharmaceutical Sciences Branch (IAUPS), Islamic Azad University, Tehran, Iran Abstract: Juglans regia L. (Persian walnut), is a temperate nut crop and Iran is one of its centers of origin and diversity. According to the statistics provided in 2007 by (FAO), Persian walnut grows in Iran, ranking third globally. As geographical conditions affect the nutritional value of walnuts, the objective of this study was evaluation of protein, crude fiber, fatty acids and some mineral element contents in samples in Tehran and Karaj County farmlands as two economically important provinces. Samples were collected during the 2 years harvest from 12 different distinguished cultivars of trees grown in a replicated trial in an experimental orchard. All trees under the study were of seedlings origin and are growing naturally and treating traditionally. The order depending on the contents of elements (mg/100 g) in J. regia samples in Karaj studied regions was Mg> K> Fe > Cu >Ca >Zn> Na, whereas in Tehran farmlands the order is: Mg> K> Fe > Ca >Cu >Zn> Na which shows that high levels of these elements in the soil of area, have a great impact on the highness of calcium and copper in the fruits. Total oil content ranged from 60.9 to 73.1%, while the crude protein ranged from 13.5 to 20.2%. -

Us Department of the Treasury Press Centre – 29 August 2014

US DEPARTMENT OF THE TREASURY PRESS CENTRE – 29 AUGUST 2014 WASHINGTON – Today, the U.S. Department of the Treasury announced actions targeting a diverse set of entities and individuals under various Iran-related authorities, targeting Iran’s missile and nuclear programs, sanctions evasion efforts, and support for terrorism. The Department of State also announced additional actions under its authorities. These actions reflect the United States’ sustained commitment to enforce our sanctions as the P5+1 and Iran work toward a comprehensive solution to address the international community’s concerns over Iran’s nuclear program. More specifically: • Treasury designated four individuals and two entities pursuant to Executive Order (E.O.) 13382, which targets proliferators of weapons of mass destruction (WMD) and their supporters. Treasury also identified two aliases used by a previously sanctioned key Iranian missile proliferator. • Treasury designated two entities and three individuals tied to Iran’s energy industry pursuant to E.O. 13645. Treasury also identified six vessels pursuant to this authority. • Treasury designated one entity pursuant to E.O. 13622 for its provision of material support to the Central Bank of Iran in connection with the purchase or acquisition of U.S. dollar bank notes by the Government of Iran. • Treasury identified five Iranian banks that are subject to sanctions under E.O. 13599, which blocks the property and interests in property of the Government of Iran and Iranian financial institutions. • Treasury designated four entities and one individual pursuant to E.O. 13224 in connection with Iran’s support for terrorism. Treasury also identified one alias used by an Iranian airline that was previously sanctioned under this E.O. -

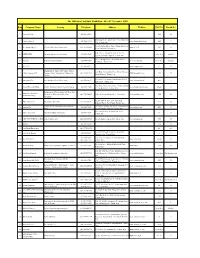

Row Company Name Activity Telephone Address Website Hall No Booth No

The 10th Auto Parts Int,l. Exhibition - 16 to 19 November 2015 Row Company Name Activity Telephone Address WebSite Hall No Booth No 1 Abarashi Group (021)36466786 31B 38 D46 Golgasht St., Golzar Ave, Parand Industrial 2 Abzar Andisheh (021)56419014 www.abzarandisheh.com 40B 7 City, Tehran- Iran No.120, Kalhor Blvd, Shahre Ghods, 20th km of 3 Ace Engineering Co Electrical Auto Part Manufacturer (021)46884888-9 www.ACE.IR 40B 16 Karaj Old Road, Tehran, Iran Unit 2, No. 4, Koopayeh Alley, Before the 4 ADIB IMENi Garment industry and advertising (021)55380846 Open Area South 31 Qazvin Sq, South Kargar St, Tehran, Iran No. 17, Dastgheib Ave, West Shahed Blvd., 5 Agradad Industrial Automatic Door (021)44588684 www.agradad.com Open Area South 31 Tehransar, Tehran, Iran 6 AL.TECH. (021)26760992 www.dinapart.com 6 38 Manufactur of Types of Steel Parts by hot Sarir Bldg., Peykanshahr Exit,15th km Tehran- 7 Alborz Forging IND forging method, Auto Gearbox, Suspension (021)44784191-5 www.forgealborz.com 40B 29 Karaj Highway, Tehran- Iran Chassis No. 18 & 19, Next to the Gas Station, West 15 8 Aluminium Faz Car Aluminium Parts (Die Casting) (021)55690137 www.aluminiumfaz.ir 40A 3 Khordad St., Tehran, Iran First Floor, No.7, Zahiroleslam Alley, Iranshahr 9 Alvand Electronic Dana Vehicle Tracking, kinds of electronic boards (021)88313640 www.alvandelectronic.com 20-22 16 St., Taleghani Ave., Tehran- Iran Production of different kind of oil filters, Fuel Aman Filter Industrial 10 filters & Air filters for light & heavy (021)77167003-5 Unit 6, 3rd Floor, Piroozi Ave, Tehran, Iran www.amanfilter.com 31B 28 Production Group automobile No.207, 208- F, Sarv 24 St, Nasirabad 11 Aman Ghate Kar Automobile spare parts (021)56390795 20-22 20 Industrial Town, Saveh Road, Tehran, Iran Manufacturing Auto suspension & steering 1st Eastern 20 Meter St., Tabriz Exhibition old 12 Amirnia Co. -

Refrence-Projects.Pdf

Dear all, The following collection contains some of references projects in which PMA or KALE porcelain ceramic tiles have been used. Thanks to all designers, architects, contractors and others who have contributed to create these precious works, I urge myself to make some remark: This collection, consists some of projects that we had access to their photos and documents, it has been published in limited edition and will be distributed in some authorized employers, architects and contractor’s offices. We hope to publish better photos accompanied with architectural explanations and their creators names from all worthy projects in near future and open edition. Your kind assistance to compile this rich collection I want to thank you in advance, for all your support in this project. Hope by continuing this way we could have put effective steps in introducing the valuable works in construction industry in our country. Yours sincerely Seyed Ali Ziaee Chairman of the board Pishgaman Memari Arya co. representing modern architecture through two recent decades would be highly appreciated, therefore our colleagues 04 in traning and technical support department will contact you to gather your valuable information. Also, you may update 05 us with more detailed information or any needed revision through our website www.pma. co.ir. 06 07 INDEX Residential Projects............................................................08 Bank Projects....................................................................154 Hotel Projects.....................................................................36 -

UC Berkeley UC Berkeley Electronic Theses and Dissertations

UC Berkeley UC Berkeley Electronic Theses and Dissertations Title The Rise of Iran Auto: Globalization, liberalization and network-centered development in the Islamic Republic Permalink https://escholarship.org/uc/item/3558f1v5 Author Mehri, Darius Bozorg Publication Date 2014 Peer reviewed|Thesis/dissertation eScholarship.org Powered by the California Digital Library University of California ! The$Rise$of$Iran$Auto:$Globalization,$liberalization$and$network:centered$development$in$ the$Islamic$Republic$ $ By$ $ Darius$Bozorg$Mehri$ $ A$dissertation$submitted$in$partial$satisfaction$of$the$ requirements$for$the$degree$of$ Doctor$of$Philosophy$ in$ Sociology$ in$the$ Graduate$Division$ of$the$ University$of$California,$Berkeley$ Committee$in$Charge:$ Professor$Peter$B.$Evans,$Chair$ Professor$Neil$D.$Fligstein$ Professor$Heather$A.$Haveman$ Professor$Robert$E.$Cole$ Professor$Taghi$Azadarmarki$ Spring$2015$ $ $ $ $ $ $ $ $ $ $ $ $ $ $ $ $ $ $ $ $ $ $ $ $ $ 1$ Abstract$ The$Rise$of$Iran$Auto:$Globalization,$liberalization$and$network:centered$development$in$ the$Islamic$Republic$ by$Darius$Bozorg$Mehri$ Doctor$of$Philosophy$in$Sociology$ University$of$California,$Berkeley$ Peter$B.$Evans,$Chair $ This$dissertation$makes$contributions$to$the$field$of$sociology$of$development$and$ globalization.$ It$ addresses$ how$ Iran$ was$ able$ to$ obtain$ the$ state$ capacity$ to$ develop$ the$ automobile$ industry,$ and$ how$ Iran$ transferred$ the$ technology$ to$ build$ an$ industry$ with$ autonomous,$indigenous$technical$capacity$$$ Most$ theories$ -

Department of the Treasury

Vol. 81 Monday, No. 49 March 14, 2016 Part IV Department of the Treasury Office of Foreign Assets Control Changes to Sanctions Lists Administered by the Office of Foreign Assets Control on Implementation Day Under the Joint Comprehensive Plan of Action; Notice VerDate Sep<11>2014 14:39 Mar 11, 2016 Jkt 238001 PO 00000 Frm 00001 Fmt 4717 Sfmt 4717 E:\FR\FM\14MRN2.SGM 14MRN2 jstallworth on DSK7TPTVN1PROD with NOTICES 13562 Federal Register / Vol. 81, No. 49 / Monday, March 14, 2016 / Notices DEPARTMENT OF THE TREASURY Department of the Treasury (not toll free Individuals numbers). 1. AFZALI, Ali, c/o Bank Mellat, Tehran, Office of Foreign Assets Control SUPPLEMENTARY INFORMATION: Iran; DOB 01 Jul 1967; nationality Iran; Electronic and Facsimile Availability Additional Sanctions Information—Subject Changes to Sanctions Lists to Secondary Sanctions (individual) Administered by the Office of Foreign The SDN List, the FSE List, the NS– [NPWMD] [IFSR]. Assets Control on Implementation Day ISA List, the E.O. 13599 List, and 2. AGHA–JANI, Dawood (a.k.a. Under the Joint Comprehensive Plan additional information concerning the AGHAJANI, Davood; a.k.a. AGHAJANI, of Action JCPOA and OFAC sanctions programs Davoud; a.k.a. AGHAJANI, Davud; a.k.a. are available from OFAC’s Web site AGHAJANI, Kalkhoran Davood; a.k.a. AGENCY: Office of Foreign Assets AQAJANI KHAMENA, Da’ud); DOB 23 Apr (www.treas.gov/ofac). Certain general Control, Treasury Department. 1957; POB Ardebil, Iran; nationality Iran; information pertaining to OFAC’s Additional Sanctions Information—Subject ACTION: Notice. sanctions programs is also available via to Secondary Sanctions; Passport I5824769 facsimile through a 24-hour fax-on- (Iran) (individual) [NPWMD] [IFSR]. -

A New Method for Environmental Site Assessment of Urban Solid Waste Landfills

Environ Monit Assess DOI 10.1007/s10661-011-2034-6 A new method for environmental site assessment of urban solid waste landfills Fatemeh Ghanbari · Farham Amin Sharee · Masoud Monavari · Narges Zaredar Received: 7 June 2010 / Accepted: 16 March 2011 © Springer Science+Business Media B.V. 2011 Abstract Regarding various types of pollutant, similar methods, much more criteria (53 parame- waste management requires high attention. En- ters) can be considered within this method, so vironmental site selection study, prior to landfill the results will be more calculable. According to operation, and subsequently, monitoring and this method, Rasht landfill (site H) is classified maintaining of the location, are of foremost points as unacceptable landfill site i.e. there is an urgent in landfill site selection process. By means of these need for a new suitable site for landfill, while studies, it is possible to control the undesirable Andishe Landfill (site D) is ranked as acceptable impacts caused by landfills. Study ahead aims at landfill site but needs environmental management examination of effectiveness of a new method program to handle the existing weaknesses. called Monavari 95–2 in landfill site assessment. For this purpose, two landfills Rasht and An- Keywords Landfill site assessment · Arid area · disheh, which are, respectively, located on humid Humid area · Solid wastes · Deposition · and arid areas, were selected as case studies. Then, Waste management the results obtained from both sites were com- pared with each other to find out the weaknesses and strengths of each site. Compared with others Introduction Lack of sufficient laws and regulation and enough land for landfilling have caused several environ- mental pollutions and natural resources degrada- F. -

Index of Iranian Participant 212 2017 Company Name Page

Index of Iranian participant 212 2017 www.khoushab.com Company Name Page 0ta100 Iranian Industry 228 Abin Gostar Marlik Eng. Group 228 Abtin Sanat Dana Plast 228 Adak Starch 228 Adili Machinery Packing 228 Adonis Teb Laboratory 229 Afshan Sanatavaran Novin 229 Agricaltural Services Holding 229 Agro Food News Agency 229 Ala Sabz Kavir (Jilan) 229 Aladdin Food Ind. 230 Alborz Bahar Machine 230 Alborz Machine Karaj 230 Alborz Sarmayesh 230 Alborz Steel 230 Alia Golestan Food Ind. 231 Almas Film Azarbayjan 231 Almatoz 231 Ama 231 Amad Polymer 231 Arad Science & Technique 232 Ard Azin Neshasteh 232 Ardin Shahd 232 Argon Sanat Sepahan 232 Ari Candy Sabalan Natural & Pure Honey 232 Aria Grap Part 233 Aria Plastic Iranian 233 Arian Car Pack 233 Arian Milan 233 Arian Zagros Machine 233 Arkan Felez 234 Armaghan Behshahd Chichest (Mirnajmi Honey) 234 telegram.me/golhaco instagram:@golhaco www.golhaco.ir صدای مشرتی: 5-66262701 تلفکس: 66252490-4 club.golhaco.ir پس از هر طلوع چاشنی زندگی تان می شویم 213 www.khoushab.com 2017 Company Name Page Armaghan Chashni Toos (Arshia) 234 Armaghan Dairy (Manimas) 234 Arman Goldasht 234 Armen Goosht 235 Arvin Bokhar Heating Ind. 235 Asal Dokhte Shahd 235 Asan Kar Ind. Group 235 Asan Pack (Asan Ghazvin Pack & Print Ind.) 235 Ashena Lable 236 Ashianeh Sabz Pardisan 236 Ashkan Mehr Iranian 236 Asia Borj 236 Asia Cap Band 236 Asia Shoor 237 Atlas Tejarat Saina 237 Atrin Protein 237 Ava 237 Aytack Commercial 237 Azar Halab 238 Azar Yeshilyurt 238 Azin Masroor 238 Azooghe Shiraz 238 Bahraman Saffron 238 Barzegar Magazine 239 Barzin Sanat Koosha 239 Baspar Pishrafteh Sharif 239 Behafarin Behamin 239 Behban Shimi 239 Beheshtghandil 240 Behfar Machine Sahand 240 Behin Azma Shiraz Eng.