The Freedom to Display the American Flag Act 61

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Mary Pickersgill: the Woman Who Sewed the Star-Spangled Banner

Social Studies and the Young Learner 25 (4), pp. 27–29 ©2013 National Council for the Social Studies Mary Pickersgill: The Woman Who Sewed The Star-Spangled Banner Megan Smith and Jenny Wei Just imagine: you live in a time before electricity. There are no sewing machines, no light bulbs, and certainly no television shows to keep you entertained. You spend six days a week working 12-hours each day inside your small home with four teenage girls and your elderly mother. This was the life of Mary Pickersgill, the woman who sewed the Star-Spangled Banner. This image is the only known likeness of Mary Pickersgill, Each two-foot stripe of the flag was sewn from two widths of though it doesn’t paint an accurate picture of Mary in 1813. British wool bunting. The stars were cut from cotton. Though Visitors who see this image in the “Star-Spangled Banner” the flag seems unusually large to our eyes (nearly a quarter of online exhibition” (amhistory.si.edu/starspangledbanner) the size of a modern basketball court), it was a standard “gar- often envision Mary as a stern grandmother, sewing quietly rison” size meant to be flown from large flagpoles and seen in her rocking chair. No offense to the stern grandmoth- from miles away. ers of the world, but Mary was actually forty years Mary Pickersgill had learned the art of flag making younger than depicted here when she made the from her mother, Rebecca Young, who made a Star-Spangled Banner, and was already a suc- living during the Revolution sewing flags, blan- cessful entrepreneur. -

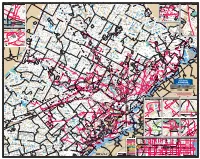

SEPTA Suburban St & Transit Map Web 2021

A B C D E F G H I J K L M N O P Q R S T U V W X Y Z AA BB CC Stoneback Rd Old n d California Rd w d Rd Fretz Rd R o t n R d Dr Pipersville o Rd Smiths Corner i Rd Run Rd Steinsburg t n w TohickonRd Eagle ta Pk Rolling 309 a lo STOCKTON S l l Hill g R Rd Kellers o Tollgate Rd in h HAYCOCK Run Island Keiser p ic Rd H Cassel um c h Rd P Portzer i Tohickon Rd l k W West a r Hendrick Island Tavern R n Hills Run Point Pleasant Tohickon a Norristown Pottstown Doylestown L d P HellertownAv t 563 Slotter Bulls Island Brick o Valley D Elm Fornance St o i Allentown Brick TavernBethlehem c w Carversvill- w Rd Rd Mervine k Rd n Rd d Pottsgrove 55 Rd Rd St Pk i Myers Rd Sylvan Rd 32 Av n St Poplar St e 476 Delaware Rd 90 St St Erie Nockamixon Rd r g St. John's Av Cabin NJ 29 Rd Axe Deer Spruce Pond 9th Thatcher Pk QUAKERTOWN Handle R Rd H.S. Rd State Park s St. Aloysius Rd Rd l d Mill End l La Cemetery Swamp Rd 500 202 School Lumberville Pennsylvania e Bedminster 202 Kings Mill d Wismer River B V Orchard Rd Rd Creek u 1 Wood a W R S M c Cemetery 1 Broad l W Broad St Center Bedminster Park h Basin le Cassel Rockhill Rd Comfort e 1100 y Weiss E Upper Bucks Co. -

Early Morning Encounter with 'The Director'

Volume 9 No 18 Publishedat UCSD 17thyear of publication May 29th- June Ilth 1984 CenterVote Irregularities ,/ Cast Doubt VOTER TURNOUT STILL AT DOUBT Amidsthighly suspect and irregular conditions.UCSD undergraduatesand graduatesvoted last week by a marginof 54.4%to 45.6%to assessthemselves $75 per quarter in increased fees "to representthe ongoing commitmentof the UCSD Studentbody tocontributeto the construction, operation and maintenence of University Center facilities."The turnoutwas a mere 89 votesabove the administration’sclaim of 20% of the campus population. r Opponentsargued a 25% aurnout and 2/3rd majority was required for ratification. Controversysarrounded the entire weekof votingfollowing a request,May 22rid.by the Committeefor Responsible Spending(CRS) urgingVice Chancellor of UndergraduateAffairs, 3oe Watson, Turnage Over Coffee "To clarifyand reverse the obvious disclosedhe wouldbe out of townuntil afterthe polls closed on Friday.May 25. deviation from established campus regulations by proponents of the This left unanswered, the CRS contentionon the minimum required Early Morning Encounter UniversityCenter regardingminimum turnout,and gave the administrationthe voterturnout for referendums,such as opportunityto reviewthe outcome of the this. which assessa mamlatoryfee." With ’The Director’ CRS cited campus regulations and voting beforerendering a decision. FollowingLt an interviewwith Maior Now Califorma,let me suggestone Similarly. a CRS follow-up memo precedentto indicatea 25~ minimum GeneralThomas K. Turnage.national thing,there are a numberof reasonswhy addressedto AssistantChancellor, turnoutand two-thirdsmajority vote directoro./the Selective Service Srstem. we thinkthat that occurs... PatrickLedden, urging a decisionon the requiredfor ratification of the measure. Ourfir.~t .~’(’heduied interview with the voterrequirement prior to releasingthe n.i.:That’s what i’m interested.. -

Superman Real Name: Kal-El (Krypton), Clark David Xavier (Earth) Occupation: X-Man Marital Status: Engaged to Phoenix (Jean Grey) Ht: 6'3" Wt: 225 Lbs

Superman Real Name: Kal-el (Krypton), Clark David Xavier (Earth) Occupation: X-Man Marital Status: Engaged to Phoenix (Jean Grey) Ht: 6'3" _ Wt: 225 lbs. Eyes/Hair: Blue / Black First Appearance: "What if Superman were an X-Man?" Vol. 1 (current), Action Comics #1 (June 1938) (historical) Superman is the last son of a doomed world. After the Skrulls found themselves unable to conquer Krypton, they destroyed the planet. Due to the Eradicator Virus, most Kryptonians would have died if they had left the planet, but Superman's father, Jor-el, had used an experimental serum, which left his newborn son immune to the virus. Rather than watch their son die, Jor-el and Lara chose to take a chance and send Kal-el to another world. Having studied Earth, and finding it to his liking, Jor-el sent his son there. Arriving on Earth, fate lead to Kal-el's discovery by young mutant Charles Xavier. Learning of the child's origin from a telepathic transmitter in the ship, Xavier dubbed the infant Clark, and decided to raise the boy as his own. Thus Clark became one of the founding members of the X-Men, a mutant super-hero team, dedicated to promoting peace between mutants and 'normal' humans. In this role he has encountered many hero and villains. When not out saving the world, Superman acts a linguistics teacher at the Xavier Institute, trains with his fellow X-Men, and engages in 'normal' activities (going on dates with Jean, taking the students to baseball games, etc). -

Found, Featured, Then Forgotten: U.S. Network TV News and the Vietnam Veterans Against the War © 2011 by Mark D

Found, Featured, then Forgotten Image created by Jack Miller. Courtesy of Vietnam Veterans Against the War. Found, Featured, then Forgotten U.S. Network TV News and the Vietnam Veterans Against the War Mark D. Harmon Newfound Press THE UNIVERSITY OF TENNESSEE LIBRARIES, KNOXVILLE Found, Featured, then Forgotten: U.S. Network TV News and the Vietnam Veterans Against the War © 2011 by Mark D. Harmon Digital version at www.newfoundpress.utk.edu/pubs/harmon Newfound Press is a digital imprint of the University of Tennessee Libraries. Its publications are available for non-commercial and educational uses, such as research, teaching and private study. The author has licensed the work under the Creative Commons Attribution-Noncommercial 3.0 United States License. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/3.0/us/. For all other uses, contact: Newfound Press University of Tennessee Libraries 1015 Volunteer Boulevard Knoxville, TN 37996-1000 www.newfoundpress.utk.edu ISBN-13: 978-0-9797292-8-7 ISBN-10: 0-9797292-8-9 Harmon, Mark D., (Mark Desmond), 1957- Found, featured, then forgotten : U.S. network tv news and the Vietnam Veterans Against the War / Mark D. Harmon. Knoxville, Tenn. : Newfound Press, University of Tennessee Libraries, c2011. 191 p. : digital, PDF file. Includes bibliographical references (p. [159]-191). 1. Vietnam Veterans Against the War—Press coverage—United States. 2. Vietnam War, 1961-1975—Protest movements—United States—Press coverage. 3. Television broadcasting of news—United States—History—20th century. I. Title. HE8700.76.V54 H37 2011 Book design by Jayne White Rogers Cover design by Meagan Louise Maxwell Contents Preface ..................................................................... -

Historic Flag Presentation

National Sojourners, Incorporated Historic Flag Presentation 16 July 2017 1 Table of Contents Table of Contents 2 Type of Program 4 Program Description and Background Information 4 Origin of a Historic Flag Presentation 4 What is a Historic Flag Presentation? 4 Intended Audience of a Historic Flag Presentation 4 Number required to present a Historic Flag Presentation 5 Presentation Attire 5 List of Props Needed and Where Can Props Be Obtained 5 List of Support Equipment (computer, projector, screen, etc.) 5 Special Information 5 Script for an Historic Flag Presentation 6-20 Purpose 6 General Flag Overview 6 Bedford Flag—April 1775 6 Rhode Island Regiment Flag—May 1775 8 Bunker Hill Flag—June 1775 8 Washington’s Cruisers Flag—October 1775 8 Gadsden Flag—December 1775 8 Grand Union Flag—January 1776 9 First Navy Jack—January 1776 9 First Continental Regiment Flag—March 1776 9 Betsy Ross Flag—May 1776 9 Moultrie Flag—June 1776 9 Independence Day History 9 13-Star Flag—June 1777 10 Bennington Flag—August 1777 10 Battle of Yorktown 10 Articles of Confederation 10 15-Star Flag (Star-Spangled Banner)—May 18951 11 20-Star Flag—April 1818 11 Third Republic of Texas Flag—1839-1845 11 Confederate Flag—1861-1865 12 The Pledge to the Flag 11 1909 12 48-Star Flag—September 1912-1959 13 2 World War I 12 Between the Wars 13 World War II 13 Battle of Iwo Jima 13 End of World War II 13 Flag Day 14 Korean War 14 50-Star Flag—July 1960-Present 14 Toast to the Flag 15 Old Glory Speaks 16 That Ragged Old Flag 17 3 Type of Program The Historic Flag Presentation is both a patriotic and an educational program depending on the audience. -

Hartman Kids Tour Booklet

KIDS HARTTOUR MAN TOUR Ben Hartman worked as a molder in a factory. He created objects by pouring hot liquid metal into molds. In 1932, during the Great Depression, Ben lost his job. To keep himself busy, he began creating art in his yard using concrete, stone, and anything else he could find. Ben used the skills he learned as a molder to help create his art. He was not trained as an artist. As Ben was outside of the art world, his art is often called Outsider Art. Others call it Folk Art. We just call it art! Ben used three major themes in his garden: Patriotism: Ben was a proud American and included many patriotic images in his garden, including flags and scenes from American history. Religion: Ben was a Christian and included many religious symbols and biblical stories in his garden. Education: Ben understood the importance of a good education and included many educational stories in his garden. He also built several miniature schools. Now, on your own or with a friend, WALK around the garden and find the next five objects using only the outlines provided. Hint: the first one is in the row next to the house. Betsy Ross House Ben created this miniature version of the Betsy Ross House from Philadelphia, Pennsylvania in the fall of 1932. It was one of his earliest objects in the garden. Popular history says that Betsy Ross sewed the first American flag for George Washington in 1776. In the large picture- window, Ben placed an image of Betsy Ross sewing the flag with friends. -

Travel the Usa: a Reading Roadtrip Booklist

READING ROADTRIP USA TRAVEL THE USA: A READING ROADTRIP BOOKLIST Prepared by Maureen Roberts Enoch Pratt Free Library ALABAMA Giovanni, Nikki. Rosa. New York: Henry Holt, 2005. This title describes the story of Alabama native Rosa Parks and her courageous act of defiance. (Ages 5+) Johnson, Angela. Bird. New York: Dial Books, 2004. Devastated by the loss of a second father, thirteen-year-old Bird follows her stepfather from Cleveland to Alabama in hopes of convincing him to come home, and along the way helps two boys cope with their difficulties. (10-13) Hamilton, Virginia. When Birds Could Talk and Bats Could Sing: the Adventures of Bruh Sparrow, Sis Wren and Their Friends. New York: Blue Sky Press, 1996. A collection of stories, featuring sparrows, jays, buzzards, and bats, based on African American tales originally written down by Martha Young on her father's plantation in Alabama after the Civil War. (7-10) McKissack, Patricia. Run Away Home. New York: Scholastic, 1997. In 1886 in Alabama, an eleven-year-old African American girl and her family befriend and give refuge to a runaway Apache boy. (9-12) Mandel, Peter. Say Hey!: a Song of Willie Mays. New York: Hyperion Books for Young Children, 2000. Rhyming text tells the story of Willie Mays, from his childhood in Alabama to his triumphs in baseball and his acquisition of the nickname the "Say Hey Kid." (4-8) Ray, Delia. Singing Hands. New York: Clarion Books, 2006. In the late 1940s, twelve-year-old Gussie, a minister's daughter, learns the definition of integrity while helping with a celebration at the Alabama School for the Deaf--her punishment for misdeeds against her deaf parents and their boarders. -

By David Rothfuss Fireworks and Sex! Is a New

ABSTRACT FIREWORKS AND SEX! by David Rothfuss Fireworks and Sex! is a new religion I’m launching so I can get rich without paying taxes. The religious document that follows, which you’re probably not even allowed to read on account of copyright restrictions, is pretty standard as religious documents go, providing you, the religious consumer, with 205 pages of morally ambiguous poems, fables and doodles to base your life upon. It is by far the most American religion out there, and a sure-fire path to a shinier existence, with the average follower experiencing 74% more happiness, 93% more freedom, and 87% more American Dream than those in other religions. If you were allowed to read it, which you’re not, it would provide you with an inside track to God and eternal salvation. FIREWORKS AND SEX A Field Study Guide to America’s Shiniest Religion A Thesis Submitted to the faculty of Miami University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Masters of the Arts Creative Writing/Poetry Department of English by David Alexander Rothfuss Miami University Oxford, Ohio 2011 Keith Tuma, advisor cris cheek, reader David Schloss, reader . © David Rothfuss 2011 Table of Contents: Book 1: Concerning this Book, its characters and the partial revelation of truths……………………………………………………………….………...p.1 Book 2: Concerning your new religion and how lost you would be without it…p. 52 A Brief Interlude: Poems upon which you shall base your life…………..p. 88 Book 3: Big Time: in which Our now famous characters hash out their differences with God and mortality………………………………………………………p. -

Xero Comics 4 Lupoff 1961-04

For a long time I wondered why I was unable to accept Hollywood’s premise that the Germans in World War II were either misunderstood boys (Marlon Brando in ’"The Young Lions") or really nice guys (Vari Heflin in "Under Ten Flags") while the Americans were deserters or draft dodgers (Montgomery Clift and Dean uartin, respectively, in "The Young Lions") and the British were bumbling, incompetent blowhards (Charles Laughton in "Under Ten Flags"). I was far too young, born in 1955, to remember much of the war and I lost no relatives or friends. Although two of my brothers served in the Navy in the Pacific, my family never told me much about the war. So what could I have against the Germans and Japanese? I think I have finally found the answer: the total propaganda saturation reached me through the comic books, especially through the adventures of the Sub-Mariner, the Human Torch, and Captain America, and subsidiary characters in the magazines featur ing them. 'hen you were raised on these, you learned to hate the enemy. All of these characters got their start in or around 1 959, two years before America got involved in the war, but they really came into their own when Pearl Harbor was attacked, for several reasons. Captain America, of course, was a patriotic hero-figure of a type which couldn't fully flower in peacetime when patriots are "flag-wavers," It took a full-scale war to release the unabashed patriotism which shot him to the top. The Sub-Mariner started out by marauding all shipping, with some emphasis on Amer ican vessels. -

Capitan America

Capitan America Capitan America (Captain America), il cui vero nome è Steven Grant "Steve" Rogers, è un personaggio dei fumetti creato da Joe Simon e Jack Kirby nel 1941, pubblicato dalla Timely Comics (in seguito Marvel Comics). Detto affettuosamente Cap, ha anche altri appellativi, come "Sentinella della libertà" (poiché incarna gli ideali di libertà e giustizia del popolo statunitense) e "Leggenda vivente" (in quanto fonte di ispirazione per tre generazioni di eroi), è un supereroe tra i più famosi e longevi. Il personaggio è nato come elemento di propaganda durante la seconda guerra mondiale, dove rappresentava un'America libera e democratica che si opponeva ad un'Europa imperialista e bellicosa, ed ebbe un grande successo di pubblico; tuttavia con la fine del conflitto perse la sua popolarità, nonostante un (vano) tentativo di riciclarlo come cacciatore di comunisti durante i primi anni della guerra fredda. Quando, nel 1964, Stan Lee decise di riprendere il personaggio (nel numero 4 della serie Avengers), lo privò di quegli elementi nazionalistici che aveva in origine ma lo ripropose donandogli una sensibilità e un'umanità tutta nuova, e molto spesso le sue storie venivano utilizzate per denunciare le differenze sociali e la corruzione presenti nella società americana, a rappresentare una sorta di "coscienza" reale dell'America. Il sito web IGN ha inserito Capitan America alla sesta posizione nella classifica dei cento maggiori eroi della storia dei fumetti, dopo Wonder Woman e prima di Hal Jordan. Storia editoriale Nel 1940, lo sceneggiatore Joe Simon disegnò un bozzetto di Capitan America, in un primo momento denominato 'Super American'; questo nome venne tuttavia abbandonato dallo stesso Simon per la grande diffusione di personaggi che adottavano un nome simile. -

Book Title Author Reading Level Approx. Grade Level

Approx. Reading Book Title Author Grade Level Level Anno's Counting Book Anno, Mitsumasa A 0.25 Count and See Hoban, Tana A 0.25 Dig, Dig Wood, Leslie A 0.25 Do You Want To Be My Friend? Carle, Eric A 0.25 Flowers Hoenecke, Karen A 0.25 Growing Colors McMillan, Bruce A 0.25 In My Garden McLean, Moria A 0.25 Look What I Can Do Aruego, Jose A 0.25 What Do Insects Do? Canizares, S.& Chanko,P A 0.25 What Has Wheels? Hoenecke, Karen A 0.25 Cat on the Mat Wildsmith, Brain B 0.5 Getting There Young B 0.5 Hats Around the World Charlesworth, Liza B 0.5 Have you Seen My Cat? Carle, Eric B 0.5 Have you seen my Duckling? Tafuri, Nancy/Greenwillow B 0.5 Here's Skipper Salem, Llynn & Stewart,J B 0.5 How Many Fish? Cohen, Caron Lee B 0.5 I Can Write, Can You? Stewart, J & Salem,L B 0.5 Look, Look, Look Hoban, Tana B 0.5 Mommy, Where are You? Ziefert & Boon B 0.5 Runaway Monkey Stewart, J & Salem,L B 0.5 So Can I Facklam, Margery B 0.5 Sunburn Prokopchak, Ann B 0.5 Two Points Kennedy,J. & Eaton,A B 0.5 Who Lives in a Tree? Canizares, Susan et al B 0.5 Who Lives in the Arctic? Canizares, Susan et al B 0.5 Apple Bird Wildsmith, Brain C 1 Apples Williams, Deborah C 1 Bears Kalman, Bobbie C 1 Big Long Animal Song Artwell, Mike C 1 Brown Bear, Brown Bear What Do You See? Martin, Bill C 1 Found online, 7/20/2012, http://home.comcast.net/~ngiansante/ Approx.