High School | 9Th–12Th Grade

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

American Organic Law and Government. Form #11.217

American Organic Law By: Freddy Freeman American Organic Law 1 of 247 Copyright Sovereignty Education and Defense Ministry, http://sedm.org Form #11.217, Rev. 12/12/2017 EXHIBIT:___________ Revisions Notes Updates to this release include the following: 1) Added a new section titled “From Colonies to Sovereign States.” 2) Improved the analysis on Declaration of Independence, which now covers the last half of the document. 3) Improved the section titled “Citizens Under the Articles of Confederation” 4) Improved the section titled “Art. I:8:17 – Grant of Power to Exercise Exclusive Legislation.” This new and improved write-up presents proof that the States of the United States Union were created under Article I Section 8 Clause 17 and consist exclusively of territory owned by the United States of America. 5) Improved the section titled “Citizenship in the United States of America Confederacy.” 6) Added the section titled “Constitution versus Statutory citizens of the United States.” 7) Rewrote and renamed the section titled “Erroneous Interpretations of the 14th Amendment Citizens of the United States.” This updated section proves why it is erroneous to interpret the 14th Amendment “citizens of the United States” as being a citizenry which in not domiciled on federal land. 8) Added a new section titled “the States, State Constitutions, and State Governments.” This new section includes a detailed analysis of the 1849 Constitution of the State of California. Much of this analysis applies to all of the State Constitutions. American Organic Law 3 of 247 Copyright Sovereignty Education and Defense Ministry, http://sedm.org Form #11.217, Rev. -

How Bad Were the Official Records of the Federal Convention?

How Bad Were the Official Records of the Federal Convention? Mary Sarah Bilder* ABSTRACT The official records of the ConstitutionalConvention of 1787 have been neglected and dismissed by scholars for the last century, largely to due to Max Farrand'scriticisms of both the records and the man responsible for keeping them-Secretary of the Convention William Jackson. This Article disagrees with Farrand'sconclusion that the Convention records were bad, and aims to resurrect the records and Jackson's reputation. The Article suggests that the endurance of Farrand'scritique arises in part from misinterpretationsof cer- tain proceduralcomponents of the Convention and failure to appreciate the significance of others, understandable consideringthe inaccessibility of the of- ficial records. The Article also describes the story of the records after the Con- vention but before they were published, including the physical limbo of the records in the aftermath of the Convention and the eventual deposit of the records in March 1796 amidst the rapid development of disagreements over constitutional interpretation. Finally, the Article offers a few cautionary re- flections about the lessons to be drawn from the official records. Particularly, it recommends using caution with Max Farrand's records, paying increased attention to the procedural context of the Convention, and recognizing that Constitutionalinterpretation postdated the Constitution. TABLE OF CONTENTS INTRODUCTION ................................................... 1621 A NOTE ON THE RECORDS ..................................... -

A History of George Varnum, His Son Samuel Who Came to Ipswich About

THE VARNUMS OF DRACUTT (IN MASSACHUSETTS) A HISTORY -OF- GEORGE VARNUM, HIS SON SAMUEL WHO CAME TO IPSWICH ABOUT 1635, AND GRANDSONS THOMAS, JOHN AND JOSEPH, WHO SETTLED IN DRACUTT, AND THEIR DESCENDANTS, <.tomptlet> from jfamill] ll)aper.s ant> @ffictal 'Necort>.s, -BY- JOHN MARSHALL VARNUM, OF BOSTON, 19 07. " trr:bosu mbo bo not tnasmn up tbe mimotl!: of tbdt S!nmitats bo not bumbt ta bi nmembtttb bl!: lf)osttrit11:." - EDMUND BURKE, CONTENTS. PAGE PREFACE 5 HISTORY OF THE FAMILY, BY SQUIRE PARKER VARNUM, 5 1818 9 GENEALOGY: GEORGE V ARNUM1 13 SAMUEL V ARNUM2 16 THOMAS V ARNUM3 AND HIS DESCENDANTS 23 JOHN V ARNUM3 AND HIS DESCENDANTS - 43 J°'OSEPH V ARNUM3 AND HIS DESCENDANTS - 115 SKETCH OF GEORGE V ARNAM1 13 WILL OF' GEORGE VARNAM - 14 INVENTORY OF ESTATE OF GEORGE V ARNAM - 15 SKETCH OF SAMUEL V ARNUM1 16 DEED OF SHATSWELL-VARNUM PuROHASE, 1664 17 TRANSFER OF LAND TO V ARNUMS, 1688-1735 21 SKETCH OF THOMAS VARNUM3 28 w ILL OF THOMAS VARNUM - 29 SKETCH OF SAMUEL V ARNUM4 30 INVENTORY OF ESTATE OF THOMAS V ARNUM4 31 SKETCHES OF THOMAS V ARNUM1 34 DEACON JEREMIAH V ARNUM8 35 MAJOR ATKINSON C. V ARNUM7 36 JOHN V ARNUM3 45 INVENTORY OF ESTATE OF JOHN VARNUM 41 iv VARNUM GENEALOGY. SKETCH OF LIEUT. JOHN V ARNUM4 51 JOURNAL OF LIEUT. JOHN VARNUM~ 54-64 vVILL 01' L1EuT. JoHN VARNU111• - 64-66 SKETCHES OF JONAS VARNUM4 67 ABRAHAM V ARNUl\14 68 JAMES VA RNUM4 70 SQUIRE p ARK.ER VARNUM. 74-78 COL, JAMES VARNUM" - 78-82 JONAS VARNUM6 83 CAPT. -

The Gaspee Affair As Conspiracy by Lawrence J

The Gaspee Affair as Conspiracy By Lawrence J. DeVaro, Jr. Rhode Island History, October 1973, pp. 106-121 Digitized and reformatted from .pdf available on-line courtesy RI Historical Society at: http://www.rihs.org/assetts/files/publications/1973_Oct.pdf On the afternoon of June 9, 1772, His Majesty's schooner Gaspee grounded on a shoal called Namquit Point in Narragansett Bay. From the time of their arrival in Rhode Island's waters in February, the Gaspee and her commander, Lieutenant William Dudingston, had been the cause of much commercial frustration of local merchants. Dudingston was insolent, described by one local newspaper as more imperious and haughty than the Grand Turk himself. Past accounts of his pettish nature followed him from port to port.[1] The lieutenant was also shrewd. Aware that owners of seized vessels — rather than navy captains deputized in the customs service — would triumph in any cause brought before Rhode Island's vice-admiralty court, Dudingston had favored the district vice-admiralty court at Boston instead, an option available to customs officials since 1768.[2] Aside from threatening property of Rhode Islanders through possible condemnation of seizures, utilization of the court at Boston invigorated opposition to trials out of the vicinage, a grievance which had irritated merchants within the colony for some time.[3] Finally the lieutenant was zealous — determined to be a conscientious customs officer even if it meant threatening Rhode Island's flourishing illicit trade in non-British, West-Indian molasses. Governor Joseph Wanton of Rhode Island observed that Dudingston also hounded little packet boats as they plied their way between Newport and Providence. -

The Age of Napoleon & the Triumph of Romanticism Chapter 20

The Age of Napoleon & the Triumph of Romanticism Chapter 20 The Rise of Napoleon - Chief danger to the Directory came from royalists o Émigrés returned to France o Spring 1797 – royalists won elections o To preserve the Republic . Directory staged a coup d’etat (Sept. 4, 1797) Placed their supporters back in power - Napoleon o Born 1769 on the island of Corsica . Went to French schools . Pursued military career 1785 – artillery officer . favored the revolution was a fiery Jacobin . 1793- General - Early military victories o Crushed Austria and Sardinia in Italy . Made Treaty of Camp Formino in Oct 1797 on his own accord Returned to France a hero - Britain . Only remaining enemy Too risky to cross channel o Chose to attack in Egypt . Wanted to cut off English trade and communication with India Failure - Russia Alarmed . 2nd coalition formed in 1799 Russia, Ottomans, Austria, Britain o Beat French in Italy and Switzerland 1 Constitution Year VII - Economic troubles and international situation o Directory lost support o Abbe Sieyes, proposed a new constitution . Wanted a strong executive Would require another coup d’etat o October 1799 . Napoleon left army in Egypt November 10, 1799 o Successful coup Napoleon issued the Constitution in December (Year VIII) o First Consul The Consulate in France (1799-1804) - Closed the French Revolution - Achieved wealth and property opportunities o Napoleon’s constitution was voted in overwhelmingly - Napoleon made peace with French enemies o 1801 Treaty of Luneville – took Austria out of war o 1802 Treaty of Amiens – peace with Britain o Peace at home . Employed all political factions (if they were loyal) . -

Fish Terminologies

FISH TERMINOLOGIES Monument Type Thesaurus Report Format: Hierarchical listing - class Notes: Classification of monument type records by function. -

The Signers of the U.S. Constitution

CONSTITUTIONFACTS.COM The U.S Constitution & Amendments: About the Signers (Continued) The Signers of the U.S. Constitution On September 17, 1787, the Constitutional Convention came to a close in the Assembly Room of Independence Hall in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania. There were seventy individuals chosen to attend the meetings with the initial purpose of amending the Articles of Confederation. Rhode Island opted to not send any delegates. Fifty-five men attended most of the meetings, there were never more than forty-six present at any one time, and ultimately only thirty-nine delegates actually signed the Constitution. (William Jackson, who was the secretary of the convention, but not a delegate, also signed the Constitution. John Delaware was absent but had another delegate sign for him.) While offering incredible contributions, George Mason of Virginia, Edmund Randolph of Virginia, and Elbridge Gerry of Massachusetts refused to sign the final document because of basic philosophical differences. Mainly, they were fearful of an all-powerful government and wanted a bill of rights added to protect the rights of the people. The following is a list of those individuals who signed the Constitution along with a brief bit of information concerning what happened to each person after 1787. Many of those who signed the Constitution went on to serve more years in public service under the new form of government. The states are listed in alphabetical order followed by each state’s signers. Connecticut William S. Johnson (1727-1819)—He became the president of Columbia College (formerly known as King’s College), and was then appointed as a United States Senator in 1789. -

Mary Pickersgill: the Woman Who Sewed the Star-Spangled Banner

Social Studies and the Young Learner 25 (4), pp. 27–29 ©2013 National Council for the Social Studies Mary Pickersgill: The Woman Who Sewed The Star-Spangled Banner Megan Smith and Jenny Wei Just imagine: you live in a time before electricity. There are no sewing machines, no light bulbs, and certainly no television shows to keep you entertained. You spend six days a week working 12-hours each day inside your small home with four teenage girls and your elderly mother. This was the life of Mary Pickersgill, the woman who sewed the Star-Spangled Banner. This image is the only known likeness of Mary Pickersgill, Each two-foot stripe of the flag was sewn from two widths of though it doesn’t paint an accurate picture of Mary in 1813. British wool bunting. The stars were cut from cotton. Though Visitors who see this image in the “Star-Spangled Banner” the flag seems unusually large to our eyes (nearly a quarter of online exhibition” (amhistory.si.edu/starspangledbanner) the size of a modern basketball court), it was a standard “gar- often envision Mary as a stern grandmother, sewing quietly rison” size meant to be flown from large flagpoles and seen in her rocking chair. No offense to the stern grandmoth- from miles away. ers of the world, but Mary was actually forty years Mary Pickersgill had learned the art of flag making younger than depicted here when she made the from her mother, Rebecca Young, who made a Star-Spangled Banner, and was already a suc- living during the Revolution sewing flags, blan- cessful entrepreneur. -

Benjamin Towne: the Precarious Career of a Persistent Printer

Benjamin Towne: The Precarious Career of a Persistent Printer ENJAMIN TOWNE is remembered as the publisher of America's first daily newspaper, which he brought out in Philadelphia B in the spring of 1783.1 However, the fact that he was able to print a newspaper at all during the War for Independence testifies to persistence in the face of continuing adversity worthy of at least equal note.* Towne was a man of fascinatingly fluid political views; his little newspaper, the Pennsylvania Evening 'Posty shuttled repeatedly from one end of the Revolutionary political spectrum to the other during the war. From its founding early in 1775, it was firm in its opposition to England until British soldiers occupied Philadelphia in the fall of 1777. Towne, remaining in Philadelphia, then converted his news- paper into a warm supporter of the occupying force. Subsequently, when the British marched away in June, 1778, Benjamin Towne re- mained on hand, with an ostensibly "patriotic" Evening fW/, to welcome the Americans back. This printer has been a bit of a puzzle to historians, who have noted that he was "attainted'' of treason in 1777, but that the charge was later dropped. It has also been asserted that Towne "published his newspaper undisturbed"2 even after the Americans regained Philadelphia. If true, this apparent lack of restraint would be difficult to reconcile with Leonard W. Levy's generalization that the press was nowhere free during the Revolution.3 * This study was supported in part by the Research Committee of the Graduate School, University of Wisconsin, from special funds voted by the State Legislature. -

SEPTA Suburban St & Transit Map Web 2021

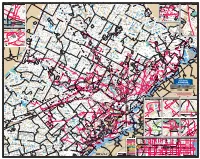

A B C D E F G H I J K L M N O P Q R S T U V W X Y Z AA BB CC Stoneback Rd Old n d California Rd w d Rd Fretz Rd R o t n R d Dr Pipersville o Rd Smiths Corner i Rd Run Rd Steinsburg t n w TohickonRd Eagle ta Pk Rolling 309 a lo STOCKTON S l l Hill g R Rd Kellers o Tollgate Rd in h HAYCOCK Run Island Keiser p ic Rd H Cassel um c h Rd P Portzer i Tohickon Rd l k W West a r Hendrick Island Tavern R n Hills Run Point Pleasant Tohickon a Norristown Pottstown Doylestown L d P HellertownAv t 563 Slotter Bulls Island Brick o Valley D Elm Fornance St o i Allentown Brick TavernBethlehem c w Carversvill- w Rd Rd Mervine k Rd n Rd d Pottsgrove 55 Rd Rd St Pk i Myers Rd Sylvan Rd 32 Av n St Poplar St e 476 Delaware Rd 90 St St Erie Nockamixon Rd r g St. John's Av Cabin NJ 29 Rd Axe Deer Spruce Pond 9th Thatcher Pk QUAKERTOWN Handle R Rd H.S. Rd State Park s St. Aloysius Rd Rd l d Mill End l La Cemetery Swamp Rd 500 202 School Lumberville Pennsylvania e Bedminster 202 Kings Mill d Wismer River B V Orchard Rd Rd Creek u 1 Wood a W R S M c Cemetery 1 Broad l W Broad St Center Bedminster Park h Basin le Cassel Rockhill Rd Comfort e 1100 y Weiss E Upper Bucks Co. -

Waterloo in Myth and Memory: the Battles of Waterloo 1815-1915 Timothy Fitzpatrick

Florida State University Libraries Electronic Theses, Treatises and Dissertations The Graduate School 2013 Waterloo in Myth and Memory: The Battles of Waterloo 1815-1915 Timothy Fitzpatrick Follow this and additional works at the FSU Digital Library. For more information, please contact [email protected] FLORIDA STATE UNIVERSITY COLLEGE OF ARTS AND SCIENCES WATERLOO IN MYTH AND MEMORY: THE BATTLES OF WATERLOO 1815-1915 By TIMOTHY FITZPATRICK A Dissertation submitted to the Department of History in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Degree Awarded: Fall Semester, 2013 Timothy Fitzpatrick defended this dissertation on November 6, 2013. The members of the supervisory committee were: Rafe Blaufarb Professor Directing Dissertation Amiée Boutin University Representative James P. Jones Committee Member Michael Creswell Committee Member Jonathan Grant Committee Member The Graduate School has verified and approved the above-named committee members, and certifies that the dissertation has been approved in accordance with university requirements. ii For my Family iii ACKNOWLEDGMENTS I would like to thank Drs. Rafe Blaufarb, Aimée Boutin, Michael Creswell, Jonathan Grant and James P. Jones for being on my committee. They have been wonderful mentors during my time at Florida State University. I would also like to thank Dr. Donald Howard for bringing me to FSU. Without Dr. Blaufarb’s and Dr. Horward’s help this project would not have been possible. Dr. Ben Wieder supported my research through various scholarships and grants. I would like to thank The Institute on Napoleon and French Revolution professors, students and alumni for our discussions, interaction and support of this project. -

H. Doc. 108-222

EIGHTEENTH CONGRESS MARCH 4, 1823, TO MARCH 3, 1825 FIRST SESSION—December 1, 1823, to May 27, 1824 SECOND SESSION—December 6, 1824, to March 3, 1825 VICE PRESIDENT OF THE UNITED STATES—DANIEL D. TOMPKINS, of New York PRESIDENT PRO TEMPORE OF THE SENATE—JOHN GAILLARD, 1 of South Carolina SECRETARY OF THE SENATE—CHARLES CUTTS, of New Hampshire SERGEANT AT ARMS OF THE SENATE—MOUNTJOY BAYLY, of Maryland SPEAKER OF THE HOUSE OF REPRESENTATIVES—HENRY CLAY, 2 of Kentucky CLERK OF THE HOUSE—MATTHEW ST. CLAIR CLARKE, 3 of Pennsylvania SERGEANT AT ARMS OF THE HOUSE—THOMAS DUNN, of Maryland; JOHN O. DUNN, 4 of District of Columbia DOORKEEPER OF THE HOUSE—BENJAMIN BIRCH, of Maryland ALABAMA GEORGIA Waller Taylor, Vincennes SENATORS SENATORS REPRESENTATIVES William R. King, Cahaba John Elliott, Sunbury Jonathan Jennings, Charlestown William Kelly, Huntsville Nicholas Ware, 8 Richmond John Test, Brookville REPRESENTATIVES Thomas W. Cobb, 9 Greensboro William Prince, 14 Princeton John McKee, Tuscaloosa REPRESENTATIVES AT LARGE Gabriel Moore, Huntsville Jacob Call, 15 Princeton George W. Owen, Claiborne Joel Abbot, Washington George Cary, Appling CONNECTICUT Thomas W. Cobb, 10 Greensboro KENTUCKY 11 SENATORS Richard H. Wilde, Augusta SENATORS James Lanman, Norwich Alfred Cuthbert, Eatonton Elijah Boardman, 5 Litchfield John Forsyth, Augusta Richard M. Johnson, Great Crossings Henry W. Edwards, 6 New Haven Edward F. Tattnall, Savannah Isham Talbot, Frankfort REPRESENTATIVES AT LARGE Wiley Thompson, Elberton REPRESENTATIVES Noyes Barber, Groton Samuel A. Foote, Cheshire ILLINOIS Richard A. Buckner, Greensburg Ansel Sterling, Sharon SENATORS Henry Clay, Lexington Ebenezer Stoddard, Woodstock Jesse B. Thomas, Edwardsville Robert P. Henry, Hopkinsville Gideon Tomlinson, Fairfield Ninian Edwards, 12 Edwardsville Francis Johnson, Bowling Green Lemuel Whitman, Farmington John McLean, 13 Shawneetown John T.