(August 21, 2013) Final Copy

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

2013 Shingwauk Gathering and Conference: Healing and Reconciliation Through Education Shingwauk 2013 Gathering and Conference Dr

2013 Shingwauk Gathering and Conference: Healing and Reconciliation Through Education Shingwauk 2013 Gathering and Conference Dr. Theresa Turmel, Con’t In her personal life, Theresa is the proud mother of three adult chil- Schedule dren, John, Danielle and Chantal and extremely proud grandmother of Ariel, Alexandra, Dylahn and Emma-Leigh and has been married to husband, Mike for the past thirty years. She achieved her BA from Lau- Friday August 2, 2013 rentian University in 1992 and her Master in Public Administration in 1998 from Lake Superior State University. Theresa possesses a love of Time Conference Gathering learning and she is guided by the traditional Anishinaabe teachings 3:00pm Lighting of the Sacred Fire and traditionalists and never wants to stop her life long learning pro- cess of culture and identity. 5:00pm- Registration and Welcome (EW 202) 7:00pm Shirley Ida (Pheasant) Williams, Kawartha Truth and Reconciliation Saturday August 3, 2013 Support Group in Peterborough Time Conference Gathering Shirley Williams - Pheasant - is a member of the Bird Clan of the Ojib- way and Odawa First Nations of Canada. Her Aboriginal name is Migizi 8:00am - Gathering and Conference Registration (EW 202) ow Kwe meaning Eagle Woman. She was born and raised at Wik- 4:00 pm wemikong, Manitoulin Island and attended St. Joseph’s Residential School in Spanish, Ontario. After completing her NS diploma, she re- 10:00am - Photo albums, displays, tours ceived her BA in Native Studies at Trent University and her Native Lan- 4:00pm (EW 202, EW 201) guage Instructors Program diploma from Lakehead University in Thun- der Bay. -

Structural Engineering Letter

P.O. Box 218, Fenwick, Ontario L0S 1C0 905-892-2110 e-mail: [email protected] August 12, 2019 Walter Basic Acting Director of Planning Town of Grimsby 160 Livingstone Avenue P.O. Box 169 Grimsby, ON L3M 4G3 Re: 133 & 137 Main Street East Dear Sir: We have been retained as heritage structural consultants for the proposed relocation of the Nelles House at 133 Main Street East in Grimsby. While we have not yet had time to develop the complete design and details for the proposed relocation, we have looked at the house and we are confident that it can be successfully moved and restored. We have reviewed your comments in your letter of July 22, 2019 to the IBI Group, specifically items 2 & 4 in the comments on the HIA. Item 2 requests clarification regarding the preservation of the stone foundation when the dwelling is moved. We believe that preservation of the visible portion of the stone foundation between grade and the brick would meet the intent of the designating bylaw and the approach which we have used on previous similar projects is to salvage the stone from the foundation, place the building on a new concrete foundation constructed with a shelf in the concrete, and re-lay the salvaged stone so no concrete is visible in the finished project. In cases where the stone wall is of particular importance, we have documented the positions of the stones and replaced them exactly as originally located on the building, although in most cases the use of the salvaged material laid in a pattern matching the original is sufficient to meet the intent. -

The Anishinabek Nation Economy Our Economic Blueprint

The Anishinabek Nation Economy Our Economic Blueprint Committee Co-Chairs: Report Prepared by: Dawn Madahbee (Aundeck Omni Kaning) Harold Tarbell, Gaspe Tarbell Associates Ray Martin (Chippewas of Nawash First Nation) Collette Manuel, CD Aboriginal Planning Our Economic Blueprint The Anishinabek Economy - Our Economic Blueprint By Harold Tarbell, Collette Manual (Gaspe Tarbell and Associates), Ray Martin and Dawn Madahbee (Union of Ontario Indians) ©2008 Union of Ontario Indians Nipissing First Nation, Ontario Canada All rights reserved. No part of this work covered by copyright may be reproduced or used in any form of by any means with expressed written consent of the Union of Ontario Indians. ISBN 1-896027-64-4 – The Anishinabek Economy - Our Economic Blueprint Union of Ontario Indians Head Office: Nipissing First Nation Highway 17 West P.O. Box 711 North Bay, Ontario P1B 8J8 The publisher greatly acknowledges the assistance of the following funders: ii | P a g e Our Economic Blueprint Acknowledgements Grand Council Chief John Beaucage and Co-Chairs Dawn Madahbee and Ray Martin November 2007 Grand Council adoption of the Economic Blueprint The “Anishinabek Nation Economy - Our Economic Blueprint” is the result of dedicated efforts of many people. It is therefore fitting to begin with words of thanks and appreciation. Harold Tarbell, Gaspe Tarbell Associates and Collette Manuel, CD Aboriginal Planning carried out research, facilitated the planning process, and wrote the strategy. Invaluable advice and direction was provided by a steering committee that was co-chaired by long-time economic and business development advocates Dawn Madahbee (Aundeck Omni Kaning) and Ray Martin (Chippewas of Nawash First Nation). -

1. Executive Summary

1. Executive Summary “The significant problems we The Looking Glass River Watershed is one of three watersheds that were face cannot be solved at the same delineated as a result of the formation of the Greater Lansing Regional level of thinking we were at Committee on Phase II Nonpoint Source Pollution Prevention (GLRC) on when they were created.” May 21, 2004. The GLRC is comprised of 22 political agencies (i.e. - Albert Einstein communities, drain commissioner’s offices, and road commission) that each chose to fulfill the requirements of the Michigan Watershed-Based National Pollutant Discharge Elimination System (NPDES) Phase II Storm Water Permit. The Looking Glass River Watershed contains 14 of the 22 political agencies. Working together as the Looking Glass River Watershed Committee, the permittees have developed this Watershed Management Plan (WMP) to fulfill the permit requirements. The Looking Glass River Watershed includes both rural and urban areas. The urban areas, which encompass approximately 11% of the watershed, Lower Grand include a portion of the Lansing metropolitan area (the Cities of Lansing, River Looking Glass River Watershed Management East Lansing, and Lansing Township), Meridian Township, and the City of Planning Area DeWitt. The City of DeWitt and Bath and DeWitt Townships are experiencing development but still have rural (agricultural and forest) areas that can be protected. Watertown, Woodhull, Victor, Olive and Riley Upper Grand Townships are all in the watershed and all have rural areas with significant River -

Community Profiles for the Oneca Education And

FIRST NATION COMMUNITY PROFILES 2010 Political/Territorial Facts About This Community Phone Number First Nation and Address Nation and Region Organization or and Fax Number Affiliation (if any) • Census data from 2006 states Aamjiwnaang First that there are 706 residents. Nation • This is a Chippewa (Ojibwe) community located on the (Sarnia) (519) 336‐8410 Anishinabek Nation shores of the St. Clair River near SFNS Sarnia, Ontario. 978 Tashmoo Avenue (Fax) 336‐0382 • There are 253 private dwellings in this community. SARNIA, Ontario (Southwest Region) • The land base is 12.57 square kilometres. N7T 7H5 • Census data from 2006 states that there are 506 residents. Alderville First Nation • This community is located in South‐Central Ontario. It is 11696 Second Line (905) 352‐2011 Anishinabek Nation intersected by County Road 45, and is located on the south side P.O. Box 46 (Fax) 352‐3242 Ogemawahj of Rice Lake and is 30km north of Cobourg. ROSENEATH, Ontario (Southeast Region) • There are 237 private dwellings in this community. K0K 2X0 • The land base is 12.52 square kilometres. COPYRIGHT OF THE ONECA EDUCATION PARTNERSHIPS PROGRAM 1 FIRST NATION COMMUNITY PROFILES 2010 • Census data from 2006 states that there are 406 residents. • This Algonquin community Algonquins of called Pikwàkanagàn is situated Pikwakanagan First on the beautiful shores of the Nation (613) 625‐2800 Bonnechere River and Golden Anishinabek Nation Lake. It is located off of Highway P.O. Box 100 (Fax) 625‐1149 N/A 60 and is 1 1/2 hours west of Ottawa and 1 1/2 hours south of GOLDEN LAKE, Ontario Algonquin Park. -

Native Americans in Michigan

Indians’ lifestyles changed dramatically with their arrival: beans, and squash also shared thanksgiving ceremonies: they Native Americans in they were exposed to new and devastating diseases, new were blessed in the spring, evoked in rain prayers in the trade goods and commodities, new weapons and tools, summer, and celebrated in the fall. ” West Bloomfield’s Past new customs, and new prejudices—most of which had The Three-Sisters Garden: Companion Planting very destructive consequences for Native Americans. Nutritional benefits aside, when grown together, corn, beans, Permanent white farmers didn’t move here in earnest and squash are also beneficial to each other. Known as until the early 1800s, after the land was acquired by the “companion planting,” this practice of intermixing crops creates U.S. a healthier garden while minimizing environmental impact. Cornstalks offer poles for beans to climb; corn leaves give Greater West Bloomfield squash shelter from the wind and sun; beans add nitrogen to When did Native Americans leave West Bloomfield? the soil; and squash provide a ground cover of living mulch, Historical Society shading the soil to help retain moisture and limit weeds. This Native Americans were gradually pushed westward as efficient and intensive agricultural method meant that each Pocket Professor Series white settlers began to flood into Michigan in the early family could subsist on about one acre of land. 1800s. Although many local land treaties were negotiated between various Indian groups and the U.S. Agriculture on Apple Island Offered annually the 3rd Weekend in May government, the most significant was the Treaty of Detroit, concluded on November 17, 1807—in which the Surveyor Samuel Carpenter, Jr. -

Aboriginal Peoples in the Superior-Greenstone Region: an Informational Handbook for Staff and Parents

Aboriginal Peoples in the Superior-Greenstone Region: An Informational Handbook for Staff and Parents Superior-Greenstone District School Board 2014 2 Aboriginal Peoples in the Superior-Greenstone Region Acknowledgements Superior-Greenstone District School Board David Tamblyn, Director of Education Nancy Petrick, Superintendent of Education Barb Willcocks, Aboriginal Education Student Success Lead The Native Education Advisory Committee Rachel A. Mishenene Consulting Curriculum Developer ~ Rachel Mishenene, Ph.D. Student, M.Ed. Edited by Christy Radbourne, Ph.D. Student and M.Ed. I would like to acknowledge the following individuals for their contribution in the development of this resource. Miigwetch. Dr. Cyndy Baskin, Ph.D. Heather Cameron, M.A. Christy Radbourne, Ph.D. Student, M.Ed. Martha Moon, Ph.D. Student, M.Ed. Brian Tucker and Cameron Burgess, The Métis Nation of Ontario Deb St. Amant, B.Ed., B.A. Photo Credits Ruthless Images © All photos (with the exception of two) were taken in the First Nations communities of the Superior-Greenstone region. Additional images that are referenced at the end of the book. © Copyright 2014 Superior-Greenstone District School Board All correspondence and inquiries should be directed to: Superior-Greenstone District School Board Office 12 Hemlo Drive, Postal Bag ‘A’, Marathon, ON P0T 2E0 Telephone: 807.229.0436 / Facsimile: 807.229.1471 / Webpage: www.sgdsb.on.ca Aboriginal Peoples in the Superior-Greenstone Region 3 Contents What’s Inside? Page Indian Power by Judy Wawia 6 About the Handbook 7 -

1989 Senate Enrolled Bill

Act No. 154 Public Acts of 1989 Approved by the Governor July 24, 1989 Filed with the Secretary of State July 27, 1989 STATE OF MICHIGAN 85TH LEGISLATURE REGULAR SESSION OF 1989 Introduced by Senators Arthurhultz and Gast ENROLLED SENATE BILL No. 287 AN ACT to make appropriations to the department of natural resources; to provide for the acquisition of land; to provide for the development of public recreation facilities; to provide for the powers and duties of certain state agencies and officials; and to provide for the expenditure of appropriations. The People of the State of Michigan enact: Sec. 1. There is appropriated for the department of natural resources to supplement former appropriations for the fiscal year ending September 30, 1989, the sum of $15,442,244.00 for land acquisition and grants and $5,147,415.00 for public recreation facility development and grants as provided in section 35 of article IX of the state constitution of 1963 and the Michigan natural resources trust fund act, Act No. 101 of the Public Acts of 1985, being sections 318.501 to 318.516 of the Michigan Compiled Laws, from the following funds: GROSS APPROPRIATIONS........................................................................................................ $ 20,589,659 Appropriated from: Special revenue funds: Michigan natural resources trust fund......................................................................................... 20,589,659 State general fund/general purpose............................................................................................. $ —0— (59) For Fiscal Year Ending Sept. 30, 1989 DEPARTMENT OF NATURAL RESOURCES A. Michigan natural resources trust fund land acquisition (by priority) 1. Manistee river-phase II, Wexford, Missaukee, Kalkaska counties (#88-100) 2. Acquisition of Woods-phase II, Oakland county (grant-in-aid to West Bloomfield township) (#88-172) 3. -

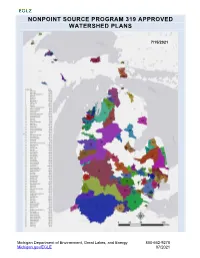

Nonpoint Source Program 319 Approved Watershed Plans

NONPOINT SOURCE PROGRAM 319 APPROVED WATERSHED PLANS 7/15/2021 Michigan Department of Environment, Great Lakes, and Energy 800-662-9278 Michigan.gov/EGLE 07/2021 NONPOINT SOURCE PROGRAM 319 APPROVED WATERSHED PLANS WITHIN LARGER 319 PLANS Page 2 NONPOINT SOURCE PROGRAM CMI APPROVED WATERSHED PLANS Page 3 NONPOINT SOURCE PROGRAM PENDING AND UPDATING WATERSHED PLANS Page 4 TABLE OF CONTENTS Nonpoint Source Program 319 Approved Watershed Plans ...................................................... 1 Nonpoint Source Program 319 Approved Watershed Plans within Larger 319 Plans ............ 2 Nonpoint Source Program CMI Approved Watershed Plans .................................................. 3 Nonpoint Source Program Pending and Updating Watershed Plans ..................................... 4 Table of Contents ...................................................................................................................... 5 Introduction .............................................................................................................................. 11 Summary of Approved Watershed Plans ................................................................................. 12 Watershed Plans ..................................................................................................................... 20 Lake Huron Initiative ............................................................................................................. 20 Cadillac District 319 Watersheds ......................................................................................... -

Niagara National Heritage Area Study

National Park Service U.S. Department of the Interior Niagara National Heritage Area Study Study Report 2005 Contents Executive Summaryr .................................................................................................. Introduction ..........................................................................................................................5 Part 1: Study Purpose and Backgroundr Project History ....................................................................................................................11 Legislation ..........................................................................................................................11 Study Process ......................................................................................................................12 Planning Context ................................................................................................................15 The Potential for Heritage Tourism ..................................................................................20 Part 2: Affected Environmentr .............................................................................. Description of the Study Area ..........................................................................................23 Natural Resources ..............................................................................................................24 Cultural Resources ..............................................................................................................26 -

Download a Map Template at Brief Descriptions of Key Events That Took Place on the Major Bodies of Water

Table of Contents INTRODUCTION Message to Teachers In this guide, borders are defined in geographic, political, national, linguistic and cultural terms. and Introduction Page 2 Sometimes they are clearly defined and other times they are abstract, though still significant to the populations affected by them. During the War of 1812, borders were often unclear as Canada, the United States and the War of 1812 Today Page 2 no proper survey had been done to define the boundaries. Border decisions were made by government leaders and frequently led to decades of disagreements. When borders changed, Borders Debate Page 4 they often affected the people living on either side by determining their nationality and their ability to trade for goods and services. Integrating Geography and History Page 5 When Canadians think of the border today, they might think of a trip to the United States on War on the Waves Page 5 vacation, but the relationship between these bordering countries is the result of over 200 Battles and Borders in Upper and Lower Canada Page 6 years of relationship-building. During the War of 1812 the border was in flames and in need of defence, but today we celebrate the peace and partnership that has lasted since then. Post-War: The Rush-Bagot Agreement Page 6 CANADA, THE UNITED STATES AND the WaR OF TeachersMessage to This guide is designed to complement “Just two miles up the road, there’s a border crossing. Through it, thousands of people pass18 to and 12 from The Historica-Dominion Institute’s the United States every day. -

Native American Indians

Native American Indians Local Camp Sites, Forts and Mounds Indian Trails Native American Indians Also see Maps Album - Maps of Native American Tribes, Trails, Camps Indian Trails in the Bedford - Walton Hills area Early Indian Trails and Villages in Pre-Pioneer Times Indian Trails Passing through our area Recorded Indian Sites in the Bedford - Walton Hills area Also see Album - Maps Archaeological Reconnaissance of the Lower Tinkers Creek Region - Also see Maps Album Tinkers Creek Valley Tinkers Creek from its Source to its Mouth, in 3 sections/pages The Many Fingers of Tinkers Creek in our area Tinkers Creek and its Tributaries 1961 map of Proposed Lake Shawnee, map 1 1961 map of Proposed Lake Shawnee, map 2 - Also see Maps Album Tinkers Creek Valley 1923-1933 Scenic and Historic Tinkers Creek Valley Map of Tinkers Creek Valley Legend and Map of Tinkers Creek Valley Legend and Map of Deerlick Creek Valley 1989 - Bedford Reservation and Cuyahoga Valley National Park areas within Walton Hills Boundaries - Also see Maps Album Special Areas of the Tinkers Creek Valley, Bedford Reservation 1923-1933 Topography and Elevations Streams Woodlands Trails and Lanes Early Residents - homes, bams Legend and Map - Places of Interest Also see Native American items on exhibit at Walton Hills Historical Resource Center, Community Room, Walton Hills Village Hall, corner of Walton and Alexander Roads, Walton Hills, Ohio CHAPTER 4 INDIAN SITES For many years, from mid Spring through Autumn, bands of woodland Indians camped in the western half of Walton Hills. Their summer campsites were near major Indian trails for east-west and north-south travel.