Depot Atypical Antipsychotics: a Review of the Clinical Effectiveness and Safety

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Standard Operating Procedure Initiation And

STANDARD OPERATING PROCEDURE Title: Procedure Document Version INITIATION AND PRESCRIBING OF PALIPERIDONE No: Replaced: LONG ACTING INJECTION (PLAI) Clinical N/A 2 SOP 03 Procedure Written By: Procedure Approved By: Approved Review Page Senior Pharmacist Gurj Bhella Date: Date: Deputy Chief Pharmacist Chief Pharmacist 22/05/2018 22/05/2020 1 of 3 Objective To ensure that all prescriptions for paliperidone are initiated by consultants on a named-patient basis and that a record of all patients is kept. Scope All BCPFT consultant teams, Pharmacy Team. Procedure 1. When a patient is identified as being a candidate for paliperidone LAI, the following criteria must be fulfilled: a. The prescribing of a typical antipsychotic depot injection first line has been tried to no effect or has not been tolerated, or is not considered clinically appropriate. b. PLAI to be initiated by Consultants only and be prescribed for its licensed indication only i.e. for maintenance treatment of schizophrenia in adult patients stabilised with risperidone (Oral or LAI) or have responded to it previously. In selected adult patients with schizophrenia and previous responsiveness to oral paliperidone or risperidone, it may be used without prior stabilisation with oral treatment if psychotic symptoms are mild to moderate and a long-acting injectable treatment is needed. Patients may now be switched from oral risperidone as well as risperidone LAI. c. PLAI must be prescribed in line with the treatment guidance for the use of long acting injections contained within NICE guideline CG178 ‘Psychosis and schizophrenia in adults: treatment and management’ issued February 2014. d. Paliperidone LAI must be prescribed once each calendar month i.e.12 times a year. -

PRODUCT INFORMATION Perphenazine Item No

PRODUCT INFORMATION Perphenazine Item No. 20735 CAS Registry No.: 58-39-9 HO Formal Name: 4-[3-(2-chloro-10H-phenothiazin-10-yl) N propyl]-1-piperazineethanol N Synonyms: NSC 150866, SCH 3940 MF: C21H26ClN3OS FW: 404.0 Purity: ≥98% N Cl UV/Vis.: λmax: 257, 312 nm Supplied as: A crystalline solid Storage: -20°C S Stability: ≥2 years Information represents the product specifications. Batch specific analytical results are provided on each certificate of analysis. Laboratory Procedures Perphenazine is supplied as a crystalline solid. A stock solution may be made by dissolving the perphenazine in the solvent of choice, which should be purged with an inert gas. Perphenazine is soluble in organic solvents such as ethanol, DMSO, and dimethyl formamide. The solubility of perphenazine in these solvents is approximately 5, 20, and 30 mg/ml, respectively. Description 1 Perphenazine is a typical antipsychotic. It binds to dopamine D2, α1A-, α2A-, α2B-, and α2C-adrenergic, M3 muscarinic, and histamine H1 receptors (Kis = 1.4, 10, 1,848, 104.9, 85.2, 810.5 and 8 nM, respectively), as well as the serotonin (5-HT) receptor subtypes 5-HT1A, 5-HT2A, 5-HT2C, 5-HT6, and 5-HT7 (Kis = 421, 5.6, 132, 17, and 23 nM, respectively). Perphenazine (1, 5, and 10 mg/kg) enhances morphine-induced analgesia in the tail-flick and hot plate tests in rats.2 It reduces cannibalism in female mice when administered at doses of 2 and 4 mg/kg.3 Formulations containing perphenazine have been used in the treatment of schizophrenia and psychosis. References 1. -

Appendix 13C: Clinical Evidence Study Characteristics Tables

APPENDIX 13C: CLINICAL EVIDENCE STUDY CHARACTERISTICS TABLES: PHARMACOLOGICAL INTERVENTIONS Abbreviations ............................................................................................................ 3 APPENDIX 13C (I): INCLUDED STUDIES FOR INITIAL TREATMENT WITH ANTIPSYCHOTIC MEDICATION .................................. 4 ARANGO2009 .................................................................................................................................. 4 BERGER2008 .................................................................................................................................... 6 LIEBERMAN2003 ............................................................................................................................ 8 MCEVOY2007 ................................................................................................................................ 10 ROBINSON2006 ............................................................................................................................. 12 SCHOOLER2005 ............................................................................................................................ 14 SIKICH2008 .................................................................................................................................... 16 SWADI2010..................................................................................................................................... 19 VANBRUGGEN2003 .................................................................................................................... -

Datasheet Inhibitors / Agonists / Screening Libraries a DRUG SCREENING EXPERT

Datasheet Inhibitors / Agonists / Screening Libraries A DRUG SCREENING EXPERT Product Name : Aripiprazole Lauroxil Catalog Number : T14319 CAS Number : 1259305-29-7 Molecular Formula : C36H51Cl2N3O4 Molecular Weight : 660.71 Description: Aripiprazole lauroxil is cleaved by body’s enzyme esterase to N-hydroxymethyl aripiprazole (plus lauric acid) and then to aripiprazole (plus formaldehyde), no toxicity[1]. Aripiprazole lauroxil, an N-acyloxymethyl prodrug of aripiprazole, is a Long-acting injectable (LAI) typical antipsychotic for schizophrenia. Storage: 2 years -80°C in solvent; 3 years -20°C powder; Receptor (IC50) Others In vivo Activity Aripiprazole lauroxil (intravenous administration; 1.87 mg/ml) bioconversion in vivo involves the formation of an intermediate, N- hydroxymethyl aripiprazole. The in vitro data indicates a high bioconversion of aripiprazole lauroxil, thus, the concentration of N- hydroxymethyl aripiprazole observed in the animals dosed with aripiprazole lauroxil is surprisingly high[1]. Reference 1. Jann MW, et al. Long-Acting Injectable Second-Generation Antipsychotics: An Update and Comparison Between Agents.CNS Drugs. 2018 Mar;32(3):241-257. 2. Rohde M, et al. Biological conversion of aripiprazole lauroxil - An N-acyloxymethyl aripiprazole prodrug.Results Pharma Sci. 2014 May 2;4:19-25. FOR RESEARCH PURPOSES ONLY. NOT FOR DIAGNOSTIC OR THERAPEUTIC USE. Information for product storage and handling is indicated on the product datasheet. Targetmol products are stable for long term under the recommended storage conditions. Our products may be shipped under different conditions as many of them are stable in the short-term at higher or even room temperatures. We ensure that the product is shipped under conditions that will maintain the quality of the reagents. -

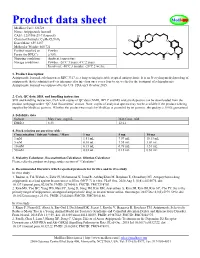

Product Data Sheet

Product data sheet MedKoo Cat#: 326728 Name: Aripiprazole lauroxil CAS#: 1259305-29-7 (lauroxil) Chemical Formula: C36H51Cl2N3O4 Exact Mass: 659.3257 Molecular Weight: 660.721 Product supplied as: Powder Purity (by HPLC): ≥ 98% Shipping conditions Ambient temperature Storage conditions: Powder: -20°C 3 years; 4°C 2 years. In solvent: -80°C 3 months; -20°C 2 weeks. 1. Product description: Aripiprazole lauroxil, aslo known as RDC 3317, is a long-acting injectable atypical antipsychotic. It is an N-acyloxymethyl prodrug of aripiprazole that is administered via intramuscular injection once every four to six weeks for the treatment of schizophrenia. Aripiprazole lauroxil was approved by the U.S. FDA on 5 October 2015. 2. CoA, QC data, SDS, and handling instruction SDS and handling instruction, CoA with copies of QC data (NMR, HPLC and MS analytical spectra) can be downloaded from the product web page under “QC And Documents” section. Note: copies of analytical spectra may not be available if the product is being supplied by MedKoo partners. Whether the product was made by MedKoo or provided by its partners, the quality is 100% guaranteed. 3. Solubility data Solvent Max Conc. mg/mL Max Conc. mM DMSO 8.33 12.61 4. Stock solution preparation table: Concentration / Solvent Volume / Mass 1 mg 5 mg 10 mg 1 mM 1.51 mL 7.57 mL 15.13 mL 5 mM 0.30 mL 1.51 mL 3.03 mL 10 mM 0.15 mL 0.76 mL 1.51 mL 50 mM 0.03 mL 0.15 mL 0.30 mL 5. -

Drug Information Sheet

University Health System PSYCHIATRIC SERVICES Antipsychotics "Depot" Injectable Typical Neuroleptics Fluphenazine Decanoate (Prolixin Decanoate®) Haloperidol Decanoate (Haldol Decanoate®) Course of Treatment: _________________________________________________________________________________ PURPOSE AND GENERAL INFORMATION 1. This medication is used to treat a variety of psychiatric problems such as overactivity, preoccupation with troublesome and recurring thoughts, and unpleasant and unusual experiences such as hearing and seeing things not normally heard nor seen. This medication will reduce or stop these experiences and help you remain outside the hospital. 2. This medication cannot "cure" the illness, but it can take away many of the symptoms or make them milder. It is important to take this medication as directed, even when you begin to feel better. It is necessary to continue taking this medication in order to keep feeling well. 3. Depot medication is an alternative to taking medicine by mouth. An injection is used to deposit medication into muscle tissue and from there the medication is slowly released into your system over a number of weeks. When medication is taken by mouth, it is quickly absorbed through the stomach and intestines; unfortunately, much of it is lost in this digestive process. 4. This medication does not produce euphoria (a high feeling) and is not addictive. BENEFITS Relief of Symptoms 1. Reduction or elimination of voices or visions not heard nor seen by others. 2. Reduction or elimination of frightening or strange beliefs and ideas not shared by others. 3. Decreased tension and agitation with more calm, relaxed feelings. 4. Improved concentration and clearer thinking; better control over thoughts and feelings with less hostile, strange, or aggressive thoughts. -

207533Orig1s000

( CENTER FOR DRUG EVALUATION AND RESEARCH APPLICATION NUMBER: 207533Orig1s000 RISK ASSESSMENT and RISK MITIGATION REVIEW(S) Department of Health and Human Services Public Health Service Food and Drug Administration Center for Drug Evaluation and Research Office of Surveillance and Epidemiology Office of Medication Error Prevention and Risk Management Risk Evaluation and Mitigation Strategy (REMS) Review Date: October 2, 2015 Reviewer(s): Cathy A. Miller, MPH, B.SN Risk Management Analyst Division of Risk Management Team Leader Kimberly Lehrfeld, Pharm.D. Division of Risk Management Acting Deputy Division Reema Mehta, Pharm.D., MPH Director Division of Risk Management Drug Name(s): Aristada (aripiprazole lauroxil) extended-release injection Therapeutic Class: Atypical Antipsychotic Dosage and Route: 441 mg/1.6 mL; 662 mg/2.4 mL; 882 mg/3.2mL intramuscular injection Application Type/Number: NDA 207533 Submission Number: ORIG-1 Submission Seq. No. 0000 dated August 22, 2014 Applicant/Sponsor: Alkermes OSE RCM #: 2014-1849 ***This document contains proprietary and confidential information that should not be released to the public*** Reference ID: 3828483 CONTENTS 1 INTRODUCTION ....................................................................................................... 1 1.1 Product Background............................................................................................ 1 1.2 Disease Background............................................................................................ 2 1.3 Regulatory History ............................................................................................. -

207533Orig1s000

CENTER FOR DRUG EVALUATION AND RESEARCH APPLICATION NUMBER: 207533Orig1s000 MEDICAL REVIEW(S) CLINICAL REVIEW Application Type NDA Application Number(s) 207553 Priority or Standard Standard Submit Date(s) 8/22/2014 Received Date(s) 8/22/2014 PDUFA Goal Date 8/22/2015 Division / Office DPP/ODE1 Reviewer Name(s) Lucas Kempf, MD Review Completion Date October 2, 2015 Established Name Aripiprazole lauroxil (Proposed) Trade Name Aristada Therapeutic Class Antipsychotic Applicant Alkermes Inc. Formulation(s) Extended release injection Dosing Regimen Suspension/ IM up to 6 weeks Indication(s) Schizophrenia Intended Population(s) Schizophrenia Template Version: March 6, 2009 Reference ID: 3806701 Clinical Review Lucas Kempf, MD NDA 207533 Aristada, Aripiprazole lauroxil Table of Contents 1 RECOMMENDATIONS/RISK BENEFIT ASSESSMENT ......................................... 7 1.1 Recommendation on Regulatory Action ............................................................. 7 1.2 Risk Benefit Assessment .................................................................................... 7 1.3 Recommendations for Postmarket Risk Evaluation and Mitigation Strategies ... 8 1.4 Recommendations for Postmarket Requirements and Commitments ................ 8 2 INTRODUCTION AND REGULATORY BACKGROUND ........................................ 8 2.1 Product Information ............................................................................................ 8 2.2 Currently Available Treatments for Proposed Indications .................................. -

Atypical Antipsychotics Step Therapy And

Atypical Antipsychotics Step Therapy and Quantity Limit Criteria Program Summary This step therapy program applies to Commercial, GenPlus, NetResults A series, NetResults F series and Health Insurance Marketplace. OBJECTIVE The intent of the Atypical Antipsychotic Step Therapy (ST) program is to encourage the use of cost-effective generic atypical antipsychotic agents over brand atypical antipsychotic agents and to accommodate for use of brand atypical antipsychotic agents when generic atypical antipsychotic agents cannot be used due to previous trial, documented intolerance, FDA labeled contraindication, or hypersensitivity. The criteria for Abilify and Abilify Discmelt encourage the use of cost-effective generic atypical antipsychotic agents or generic FDA approved agents for Tourette’s Disorder, and accommodate for the use of Abilify and Abilify Discmelt when generic atypical antipsychotic agents or generic FDA approved Tourette’s Disorder agents cannot be used due to previous trial, documented intolerance, FDA labeled contraindication, or hypersensitivity. The use of these agents for the off-label use “dementia- related psychosis” will be accommodated for shorter approval timeframes, due to concerns with safety of their use in the dementia population and based on published regulations and guidelines. The program also allows for continuation of therapy if a patient has been previously stabilized on the requested brand atypical antipsychotic. All dosage forms of the brand atypical antipsychotics listed will be included as targets in -

Effects of a Typical Antipsychotic and Thromboxane A2 Synthase Inhibitor Drug Combination on Albumin and Total Protein Level with Different Doses in Rats

Online - 2455-3891 Vol 12, Issue7, 2019 Print - 0974-2441 Research Article EFFECTS OF A TYPICAL ANTIPSYCHOTIC AND THROMBOXANE A2 SYNTHASE INHIBITOR DRUG COMBINATION ON ALBUMIN AND TOTAL PROTEIN LEVEL WITH DIFFERENT DOSES IN RATS MUHAMMAD IRFAN BASHIR* Riphah Institute of Pharmaceutical Sciences, Riphah International University, Lahore, Pakistan. Email: [email protected] Received: 14 May 2019, Revised and Accepted: 10 June 2019 ABSTRACT Objective: The objective of this study was to investigate the combined as well as individual effects of a typical antipsychotic and thromboxane A2 synthase inhibitor on albumin and total protein level with minimum and maximum dose comparison in rats. Methods: This study consisted of 100 albino rats of 300 to 340 g from both gender, there were 10 groups, each contained 10 rats (n=10). Rats were treated with defined dose of zuclopenthixol (Zuclo) and ozagrel (Ozg) for 21 days (3 weeks). Blood samples were collected at 0, 7th, 14th, and 21st days of study. Albumin and total protein level were examined from blood samples using standard laboratory procedure. Results are extracted by applying statistical analysis on data and comparing percentage variation from 0-day value. Results: A typical antipsychotic-treated group showed gradually significant increase in albumin and total protein level, TXA2 synthase inhibitor- treated group also showed significant gradually increase in albumin and total protein level in combination groups, they showed highly significant increase p<0.001 in both parameter with maximum dose. Conclusion: Combination treatment with zuclopenthixol (Zuclo) and ozagrel (Ozg) can cause large increase on albumin and total protein level with maximum dose as compare to individual drug treatment. -

Adverse Side Effects in Horses Following the Administration of Fluphenazine Decanoate

MEDICINE I Adverse Side Effects in Horses Following the Administration of Fluphenazine Decanoate John D. Baird, BVSc, PhD*; and George A. Maylin, DVM, MS, PhD Adverse behavioral side effects may occur in some horses after the intramuscular administration of fluphenazine decanoate. In severe cases, these side effects are difficult to manage and may be life-threatening to the horse, stable personnel, and treating veterinarians. The drug is not approved for use in the horse, and testing for fluphenazine is now conducted by various regulatory organizations involved in racing and equestrian competitions. Authors’ addresses: Department of Clinical Stud- ies, Ontario Veterinary College, University of Guelph, Guelph, ON Canada N1G 2W1 (Baird); and Equine Drug Testing and Research Program, New York Drug Testing and Research Program Mor- risville State College, 777 Warren Road, Ithaca, NY 14850 (Maylin); e-mail: jbaird@ovc. uoguelph.ca. *Corresponding author. © 2011 AAEP. 1. Introduction more commonly used clinically than fluphenazine Fluphenazine is a trifluoromethyl phenothiazine enanthate. In humans, the most common dosage of derivative (Fig. 1). The systematic International fluphenazine decanoate is 25 mg (range, 12.5 to 50 Union of Pure and Applied Chemistry (IUPAC) mg), with patients injected once every 2 weeks name of fluphenazine is 2-[4-[3-[2-(trifluoromethyl) (range, 1 to 4 weeks).1,5,6 After the IM injection of phenothiazin-10-yl]propyl]-piperazin-1-yl]ethanol fluphenazine decanoate, the drug gradually diffuses and it has the following structural formula. from the oily vehicle into the surrounding lymph nodes and tissues. Once the drug enters the tissue, 2. Clinical Pharmacology it is rapidly hydrolyzed by ubiquitous esterases, and Fluphenazine is a highly potent antipsychotic drug the parent compound (fluphenazine) is released. -

PRODUCT INFORMATION Cis-Flupenthixol (Hydrochloride) Item No

PRODUCT INFORMATION cis-Flupenthixol (hydrochloride) Item No. 17634 CAS Registry No.: 51529-01-2 4-[3-[(3Z)-2-(trifluoromethyl)-9H- Formal Name: OH thioxanthen-9-ylidene]propyl]-1- N piperazineethanol, dihydrochloride Synonym: cis-Flupentixol N MF: C H F N OS • 2HCl 23 25 3 2 • 2HCl FW: 507.4 CF3 Purity: ≥95% UV/Vis.: λmax: 230 nm Supplied as: A crystalline solid S Storage: -20°C Stability: ≥2 years Information represents the product specifications. Batch specific analytical results are provided on each certificate of analysis. Laboratory Procedures cis-Flupenthixol (hydrochloride) is supplied as a crystalline solid. A stock solution may be made by dissolving the cis-flupenthixol (hydrochloride) in the solvent of choice. cis-Flupenthixol (hydrochloride) is soluble in organic solvents such as ethanol, DMSO, and dimethyl formamide, which should be purged with an inert gas. The solubility of cis-flupenthixol (hydrochloride) in these solvents is approximately 1, 25, and 15 mg/ml, respectively. Further dilutions of the stock solution into aqueous buffers or isotonic saline should be made prior to performing biological experiments. Ensure that the residual amount of organic solvent is insignificant, since organic solvents may have physiological effects at low concentrations. Organic solvent-free aqueous solutions of cis-flupenthixol (hydrochloride) can be prepared by directly dissolving the crystalline solid in aqueous buffers. The solubility of cis-flupenthixol (hydrochloride) in PBS, pH 7.2, is approximately 10 mg/ml. We do not recommend storing the aqueous solution for more than one day. Description cis-Flupenthixol is a typical antipsychotic, a dopamine D2 receptor antagonist (Ki = 0.38 nM), and an 1 inverse agonist at the serotonin (5-HT) receptor subtype 5-HT2A (Ki = 7 nM).