A Systematic Review of Combination and Volume 1, Issue 1B High-Dose Atypical Antipsychotic Therapy December 2011 in Patients with Schizophrenia

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

When Clozapine Is Not Tolerated Mitchell J

University of North Dakota UND Scholarly Commons Nursing Capstones Department of Nursing 10-28-2018 When Clozapine is Not Tolerated Mitchell J. Relf Follow this and additional works at: https://commons.und.edu/nurs-capstones Recommended Citation Relf, Mitchell J., "When Clozapine is Not Tolerated" (2018). Nursing Capstones. 268. https://commons.und.edu/nurs-capstones/268 This Independent Study is brought to you for free and open access by the Department of Nursing at UND Scholarly Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Nursing Capstones by an authorized administrator of UND Scholarly Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Running head: WHEN CLOZAPINE IS NOT TOLERATED 1 WHEN CLOZAPINE IS NOT TOLERATED by Mitchell J. Relf Masters of Science in Nursing, University of North Dakota, 2018 An Independent Study Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of the University of North Dakota in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Science Grand Forks, North Dakota December 2018 WHEN CLOZAPINE IS NOT TOLERATED 2 PERMISSION Title When Clozapine is Not Tolerated Department Nursing Degree Master of Science In presenting this independent study in partial fulfillment of the requirements for a graduate degree from the University of North Dakota, I agree that the College of Nursing and Professional Disciplines of this University shall make it freely available for inspection. I further agree that permission for extensive copying or electronic access for scholarly purposes may be granted by the professor who supervised my independent study work or, in her absence, by the chairperson of the department or the dean of the School of Graduate Studies. -

Treatment of Psychosis: 30 Years of Progress

Journal of Clinical Pharmacy and Therapeutics (2006) 31, 523–534 REVIEW ARTICLE Treatment of psychosis: 30 years of progress I. R. De Oliveira* MD PhD andM.F.Juruena MD *Department of Neuropsychiatry, School of Medicine, Federal University of Bahia, Salvador, BA, Brazil and Department of Psychological Medicine, Institute of Psychiatry, King’s College, University of London, London, UK phrenia. Thirty years ago, psychiatrists had few SUMMARY neuroleptics available to them. These were all Background: Thirty years ago, psychiatrists had compounds, today known as conventional anti- only a few choices of old neuroleptics available to psychotics, and all were liable to cause severe extra them, currently defined as conventional or typical pyramidal side-effects (EPS). Nowadays, new antipsychotics, as a result schizophrenics had to treatments are more ambitious, aiming not only to suffer the severe extra pyramidal side effects. improve psychotic symptoms, but also quality of Nowadays, new treatments are more ambitious, life and social reinsertion. We briefly but critically aiming not only to improve psychotic symptoms, outline the advances in diagnosis and treatment but also quality of life and social reinsertion. Our of schizophrenia, from the mid 1970s up to the objective is to briefly but critically review the present. advances in the treatment of schizophrenia with antipsychotics in the past 30 years. We conclude DIAGNOSIS OF SCHIZOPHRENIA that conventional antipsychotics still have a place when just the cost of treatment, a key factor in Up until the early 1970s, schizophrenia diagnoses poor regions, is considered. The atypical anti- remained debatable. The lack of uniform diagnostic psychotic drugs are a class of agents that have criteria led to relative rates of schizophrenia being become the most widely used to treat a variety of very different, for example, in New York and psychoses because of their superiority with London, as demonstrated in an important study regard to extra pyramidal symptoms. -

Dopamine D2 Receptor Occupancy by Perospirone: a Positron Emission Tomography Study in Patients with Schizophrenia and Healthy Subjects

Psychopharmacology (2010) 209:285–290 DOI 10.1007/s00213-010-1783-1 ORIGINAL INVESTIGATION Dopamine D2 receptor occupancy by perospirone: a positron emission tomography study in patients with schizophrenia and healthy subjects Ryosuke Arakawa & Hiroshi Ito & Akihiro Takano & Masaki Okumura & Hidehiko Takahashi & Harumasa Takano & Yoshiro Okubo & Tetsuya Suhara Received: 3 September 2009 /Accepted: 18 January 2010 /Published online: 27 March 2010 # Springer-Verlag 2010 Abstract striatum of healthy subjects was 74.8% at 1.5 h, 60.1% at Rationale Perospirone is a novel second-generation antipsy- 8 h, and 31.9% at 25.5 h after administration. chotic drug with high affinity to dopamine D2 receptor and Conclusion Sixteen milligrams of perospirone caused over short half-life of plasma concentration. There has been no 70% dopamine D2 receptor occupancy near its peak level, investigation of dopamine D2 receptor occupancy in patients and then occupancy dropped to about half after 22 h. The with schizophrenia and the time course of occupancy by time courses of receptor occupancy and plasma concentra- antipsychotics with perospirone-like properties. tion were quite different. This single dosage may be Objective We investigated dopamine D2 receptor occupan- sufficient for the treatment of schizophrenia and might be cy by perospirone in patients with schizophrenia and the useful as a new dosing schedule choice. time course of occupancy in healthy subjects. Materials and methods Six patients with schizophrenia Keywords Dopamine D2 receptor occupancy. taking 16–48 mg/day of perospirone participated. Positron Perospirone . Positron emission tomography . emission tomography (PET) scans using [11C]FLB457 were Schizophrenia . Time course performed on each subject, and dopamine D2 receptor occupancies were calculated. -

Standard Operating Procedure Initiation And

STANDARD OPERATING PROCEDURE Title: Procedure Document Version INITIATION AND PRESCRIBING OF PALIPERIDONE No: Replaced: LONG ACTING INJECTION (PLAI) Clinical N/A 2 SOP 03 Procedure Written By: Procedure Approved By: Approved Review Page Senior Pharmacist Gurj Bhella Date: Date: Deputy Chief Pharmacist Chief Pharmacist 22/05/2018 22/05/2020 1 of 3 Objective To ensure that all prescriptions for paliperidone are initiated by consultants on a named-patient basis and that a record of all patients is kept. Scope All BCPFT consultant teams, Pharmacy Team. Procedure 1. When a patient is identified as being a candidate for paliperidone LAI, the following criteria must be fulfilled: a. The prescribing of a typical antipsychotic depot injection first line has been tried to no effect or has not been tolerated, or is not considered clinically appropriate. b. PLAI to be initiated by Consultants only and be prescribed for its licensed indication only i.e. for maintenance treatment of schizophrenia in adult patients stabilised with risperidone (Oral or LAI) or have responded to it previously. In selected adult patients with schizophrenia and previous responsiveness to oral paliperidone or risperidone, it may be used without prior stabilisation with oral treatment if psychotic symptoms are mild to moderate and a long-acting injectable treatment is needed. Patients may now be switched from oral risperidone as well as risperidone LAI. c. PLAI must be prescribed in line with the treatment guidance for the use of long acting injections contained within NICE guideline CG178 ‘Psychosis and schizophrenia in adults: treatment and management’ issued February 2014. d. Paliperidone LAI must be prescribed once each calendar month i.e.12 times a year. -

Centre for Reviews and Dissemination

Second-generation versus first-generation antipsychotic drugs for schizophrenia: a meta- analysis Leucht S, Corves C, D Arbter, Engel R R, Li C, Davis J M CRD summary The authors concluded that amisulpride, clozapine, olanzapine and risperidone can be effective in treating schizophrenia patients. Second-generation antipsychotic drugs can also result in fewer extrapyramidal side effects, but can induce weight gain. The authors' conclusions reflected the evidence presented, but some potential methodological flaws in the review process meant that the extent to which those conclusions were reliable was unclear. Authors' objectives To compare the effects of first and second-generation antipsychotic drugs in schizophrenia patients. Searching The search for eligible studies was started in 2005, including MEDLINE to October 2006, Cochrane Schizophrenia Group's Specialised Register and the US Food and Drugs Administration website. Search terms were reported and there were no language restrictions. Previous reviews were searched for additional relevant studies. Study selection Randomised controlled trials (RCTs) of oral second-generation antipsychotic drugs (amisulpride, aripiprazole, clozapine, olanzapine, quetiapine, risperidone, sertindole, ziprasidone and zotepine) compared with first-generation drugs in patients with schizophrenia or related disorders (schizoaffective, schizophreniform or delusional disorders) irrespective of diagnostic criteria were eligible for inclusion in the review. The optimum doses of second-generation drugs were selected -

Quantitative Resting State Electroencephalography in Patients with Schizophrenia Spectrum Disorders Treated with Strict Monotherapy Using Atypical Antipsychotics

Original Article https://doi.org/10.9758/cpn.2021.19.2.313 pISSN 1738-1088 / eISSN 2093-4327 Clinical Psychopharmacology and Neuroscience 2021;19(2):313-322 Copyrightⓒ 2021, Korean College of Neuropsychopharmacology Quantitative Resting State Electroencephalography in Patients with Schizophrenia Spectrum Disorders Treated with Strict Monotherapy Using Atypical Antipsychotics Takashi Ozaki1,2, Atsuhito Toyomaki1, Naoki Hashimoto1, Ichiro Kusumi1 1Department of Psychiatry, Graduate School of Medicine, Hokkaido University, 2Department of Psychiatry, Hokkaido Prefectural Koyogaoka Hospital, Sapporo, Japan Objective: The effect of antipsychotic drugs on quantitative electroencephalography (EEG) has been mainly examined by the administration of a single test dose or among patients using combinations of other psychotropic drugs. We therefore investigated the effects of strict monotherapy with antipsychotic drugs on quantitative EEG among schizophrenia patients. Methods: Data from 2,364 medical reports with EEG results from psychiatric patients admitted to the Hokkaido University Hospital were used. We extracted EEG records of patients who were diagnosed with schizophrenia spectrum disorders and who were either undergoing strict antipsychotic monotherapy or were completely free of psychotropic drugs. The spectral power was compared between drug-free patients and patients using antipsychotic drugs. We also performed multiple regression analysis to evaluate the relationship between spectral power and the chlorpromazine equivalent daily dose of antipsychotics in all the patients. Results: We included 31 monotherapy and 20 drug-free patients. Compared with drug-free patients, patients receiving antipsychotic drugs demonstrated significant increases in theta, alpha and beta power. When patients taking different types of antipsychotics were compared with drug-free patients, we found no significant change in any spectrum power for the aripiprazole or blonanserin groups. -

Lurasidone (Latuda) Reference Number: CP.PMN.50 Effective Date: 09.01.15 Last Review Date: 02.21 Line of Business: Commercial, HIM, Medicaid Revision Log

Clinical Policy: Lurasidone (Latuda) Reference Number: CP.PMN.50 Effective Date: 09.01.15 Last Review Date: 02.21 Line of Business: Commercial, HIM, Medicaid Revision Log See Important Reminder at the end of this policy for important regulatory and legal information. Description Lurasidone (Latuda®) is an atypical antipsychotic. FDA Approved Indication(s) Latuda is indicated for the treatment of: • Schizophrenia in adults and adolescents (13 to 17 years) • Depressive episode associated with bipolar I disorder (bipolar depression) in adults and pediatric patients (10 to 17 years) as monotherapy • Depressive episode associated with bipolar I disorder (bipolar depression) in adults as adjunctive therapy with lithium or valproate Policy/Criteria Provider must submit documentation (such as office chart notes, lab results or other clinical information) supporting that member has met all approval criteria. It is the policy of health plans affiliated with Centene Corporation® that Latuda is medically necessary when the following criteria are met: I. Initial Approval Criteria A. Bipolar Disorder (must meet all): 1. Diagnosis of bipolar disorder; 2. Age ≥ 10 years; 3. Failure of two preferred atypical antipsychotics (e.g., aripiprazole, ziprasidone, quetiapine, risperidone, or olanzapine) at up to maximally indicated doses, each used for ≥ 4 weeks, unless all are contraindicated or clinically significant adverse effects are experienced; 4. Dose does not exceed 120 mg per day for adults and 80 mg per day for pediatric patients. Approval duration: Medicaid/HIM – 12 months Commercial – Length of Benefit B. Schizophrenia (must meet all): 1. Diagnosis of schizophrenia; 2. Age ≥ 13 years; 3. Failure of two preferred atypical antipsychotics (e.g., aripiprazole, ziprasidone, quetiapine, risperidone, or olanzapine) at up to maximally indicated doses, each used Page 1 of 6 CLINICAL POLICY Lurasidone for ≥ 4 weeks, unless all are contraindicated or clinically significant adverse effects are experienced; 4. -

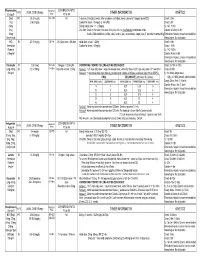

Medication Conversion Chart

Fluphenazine FREQUENCY CONVERSION RATIO ROUTE USUAL DOSE (Range) (Range) OTHER INFORMATION KINETICS Prolixin® PO to IM Oral PO 2.5-20 mg/dy QD - QID NA ↑ dose by 2.5mg/dy Q week. After symptoms controlled, slowly ↓ dose to 1-5mg/dy (dosed QD) Onset: ≤ 1hr 1mg (2-60 mg/dy) Caution for doses > 20mg/dy (↑ risk EPS) Cmax: 0.5hr 2.5mg Elderly: Initial dose = 1 - 2.5mg/dy t½: 14.7-15.3hr 5mg Oral Soln: Dilute in 2oz water, tomato or fruit juice, milk, or uncaffeinated carbonated drinks Duration of Action: 6-8hr 10mg Avoid caffeinated drinks (coffee, cola), tannics (tea), or pectinates (apple juice) 2° possible incompatibilityElimination: Hepatic to inactive metabolites 5mg/ml soln Hemodialysis: Not dialyzable HCl IM 2.5-10 mg/dy Q6-8 hr 1/3-1/2 po dose = IM dose Initial dose (usual): 1.25mg Onset: ≤ 1hr Immediate Caution for doses > 10mg/dy Cmax: 1.5-2hr Release t½: 14.7-15.3hr 2.5mg/ml Duration Action: 6-8hr Elimination: Hepatic to inactive metabolites Hemodialysis: Not dialyzable Decanoate IM 12.5-50mg Q2-3 wks 10mg po = 12.5mg IM CONVERTING FROM PO TO LONG-ACTING DECANOATE: Onset: 24-72hr (4-72hr) Long-Acting SC (12.5-100mg) (1-4 wks) Round to nearest 12.5mg Method 1: 1.25 X po daily dose = equiv decanoate dose; admin Q2-3wks. Cont ½ po daily dose X 1st few mths Cmax: 48-96hr 25mg/ml Method 2: ↑ decanoate dose over 4wks & ↓ po dose over 4-8wks as follows (accelerate taper for sx of EPS): t½: 6.8-9.6dy (single dose) ORAL DECANOATE (Administer Q 2 weeks) 15dy (14-100dy chronic administration) ORAL DOSE (mg/dy) ↓ DOSE OVER (wks) INITIAL DOSE (mg) TARGET DOSE (mg) DOSE OVER (wks) Steady State: 2mth (1.5-3mth) 5 4 6.25 6.25 0 Duration Action: 2wk (1-6wk) Elimination: Hepatic to inactive metabolites 10 4 6.25 12.5 4 Hemodialysis: Not dialyzable 20 8 6.25 12.5 4 30 8 6.25 25 4 40 8 6.25 25 4 Method 3: Admin equivalent decanoate dose Q2-3wks. -

Management of Side Effects of Antipsychotics

Management of side effects of antipsychotics Oliver Freudenreich, MD, FACLP Co-Director, MGH Schizophrenia Program www.mghcme.org Disclosures I have the following relevant financial relationship with a commercial interest to disclose (recipient SELF; content SCHIZOPHRENIA): • Alkermes – Consultant honoraria (Advisory Board) • Avanir – Research grant (to institution) • Janssen – Research grant (to institution), consultant honoraria (Advisory Board) • Neurocrine – Consultant honoraria (Advisory Board) • Novartis – Consultant honoraria • Otsuka – Research grant (to institution) • Roche – Consultant honoraria • Saladax – Research grant (to institution) • Elsevier – Honoraria (medical editing) • Global Medical Education – Honoraria (CME speaker and content developer) • Medscape – Honoraria (CME speaker) • Wolters-Kluwer – Royalties (content developer) • UpToDate – Royalties, honoraria (content developer and editor) • American Psychiatric Association – Consultant honoraria (SMI Adviser) www.mghcme.org Outline • Antipsychotic side effect summary • Critical side effect management – NMS – Cardiac side effects – Gastrointestinal side effects – Clozapine black box warnings • Routine side effect management – Metabolic side effects – Motor side effects – Prolactin elevation • The man-in-the-arena algorithm www.mghcme.org Receptor profile and side effects • Alpha-1 – Hypotension: slow titration • Dopamine-2 – Dystonia: prophylactic anticholinergic – Akathisia, parkinsonism, tardive dyskinesia – Hyperprolactinemia • Histamine-1 – Sedation – Weight gain -

)&F1y3x PHARMACEUTICAL APPENDIX to THE

)&f1y3X PHARMACEUTICAL APPENDIX TO THE HARMONIZED TARIFF SCHEDULE )&f1y3X PHARMACEUTICAL APPENDIX TO THE TARIFF SCHEDULE 3 Table 1. This table enumerates products described by International Non-proprietary Names (INN) which shall be entered free of duty under general note 13 to the tariff schedule. The Chemical Abstracts Service (CAS) registry numbers also set forth in this table are included to assist in the identification of the products concerned. For purposes of the tariff schedule, any references to a product enumerated in this table includes such product by whatever name known. Product CAS No. Product CAS No. ABAMECTIN 65195-55-3 ACTODIGIN 36983-69-4 ABANOQUIL 90402-40-7 ADAFENOXATE 82168-26-1 ABCIXIMAB 143653-53-6 ADAMEXINE 54785-02-3 ABECARNIL 111841-85-1 ADAPALENE 106685-40-9 ABITESARTAN 137882-98-5 ADAPROLOL 101479-70-3 ABLUKAST 96566-25-5 ADATANSERIN 127266-56-2 ABUNIDAZOLE 91017-58-2 ADEFOVIR 106941-25-7 ACADESINE 2627-69-2 ADELMIDROL 1675-66-7 ACAMPROSATE 77337-76-9 ADEMETIONINE 17176-17-9 ACAPRAZINE 55485-20-6 ADENOSINE PHOSPHATE 61-19-8 ACARBOSE 56180-94-0 ADIBENDAN 100510-33-6 ACEBROCHOL 514-50-1 ADICILLIN 525-94-0 ACEBURIC ACID 26976-72-7 ADIMOLOL 78459-19-5 ACEBUTOLOL 37517-30-9 ADINAZOLAM 37115-32-5 ACECAINIDE 32795-44-1 ADIPHENINE 64-95-9 ACECARBROMAL 77-66-7 ADIPIODONE 606-17-7 ACECLIDINE 827-61-2 ADITEREN 56066-19-4 ACECLOFENAC 89796-99-6 ADITOPRIM 56066-63-8 ACEDAPSONE 77-46-3 ADOSOPINE 88124-26-9 ACEDIASULFONE SODIUM 127-60-6 ADOZELESIN 110314-48-2 ACEDOBEN 556-08-1 ADRAFINIL 63547-13-7 ACEFLURANOL 80595-73-9 ADRENALONE -

The Effects of Antipsychotic Treatment on Metabolic Function: a Systematic Review and Network Meta-Analysis

The effects of antipsychotic treatment on metabolic function: a systematic review and network meta-analysis Toby Pillinger, Robert McCutcheon, Luke Vano, Katherine Beck, Guy Hindley, Atheeshaan Arumuham, Yuya Mizuno, Sridhar Natesan, Orestis Efthimiou, Andrea Cipriani, Oliver Howes ****PROTOCOL**** Review questions 1. What is the magnitude of metabolic dysregulation (defined as alterations in fasting glucose, total cholesterol, low density lipoprotein (LDL) cholesterol, high density lipoprotein (HDL) cholesterol, and triglyceride levels) and alterations in body weight and body mass index associated with short-term (‘acute’) antipsychotic treatment in individuals with schizophrenia? 2. Does baseline physiology (e.g. body weight) and demographics (e.g. age) of patients predict magnitude of antipsychotic-associated metabolic dysregulation? 3. Are alterations in metabolic parameters over time associated with alterations in degree of psychopathology? 1 Searches We plan to search EMBASE, PsycINFO, and MEDLINE from inception using the following terms: 1 (Acepromazine or Acetophenazine or Amisulpride or Aripiprazole or Asenapine or Benperidol or Blonanserin or Bromperidol or Butaperazine or Carpipramine or Chlorproethazine or Chlorpromazine or Chlorprothixene or Clocapramine or Clopenthixol or Clopentixol or Clothiapine or Clotiapine or Clozapine or Cyamemazine or Cyamepromazine or Dixyrazine or Droperidol or Fluanisone or Flupehenazine or Flupenthixol or Flupentixol or Fluphenazine or Fluspirilen or Fluspirilene or Haloperidol or Iloperidone -

Maternal Use of Psychiatric Medications During Pregnancy And

MATERNAL USE OF PSYCHIATRIC MEDICATIONS DURING PREGNANCY AND ADVERSE BIRTH OUTCOMES AND NEURODEVELOPMENTAL PROBLEMS IN OFFSPRING Ayesha C. Sujan Submitted to the faculty of the University Graduate School in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree Doctor of Philosophy in the Department of Psychological and Brain Sciences, Indiana University July 2021 ii Accepted by the Graduate Faculty, Indiana University, in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy. Doctoral Committee _______________________________________________ Brian M. D’Onofrio, PhD _______________________________________________ Richard Viken, PhD _______________________________________________ Patrick D. Quinn, PhD _______________________________________________ Christina Ludema, PhD _______________________________________________ A. Sara Oberg, PhD, MD April 22nd, 2020 iii © 2021 Ayesha C. Sujan iv Ayesha Sujan MATERNAL USE OF PSYCHIATRIC MEDICATIONS DURING PREGNANCY AND ADVERSE BIRTH OUTCOMES AND NEURODEVELOPMENTAL PROBLEMS IN OFFSPRING Understanding consequences of prenatal exposure to psychiatric and analgesic medications is important because use of these medications among pregnant women is relatively common and increasing. Rodent experiments have shown effects of perinatal exposure to specific medications; however, these findings might not apply to humans. Human observational studies have been used to study prenatal exposure to psychiatric and analgesic medications rather than randomiZed control trials due to ethical concerns