Environmental Impacts of One Puppy Mill Among Many: a Case History

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

A Humane Society Starts with You for 60 Years, the Humane Society of the United HSUS States Has Made Unprecedented Change for Animals

a humane society starts with you For 60 years, The Humane Society of the United HSUS States has made unprecedented change for animals. We’ve taken on the biggest fights wherever we find them: on the VICTORIES ground, in the boardroom, in the courts and on Capitol Hill. And we work to change public opinion by bringing issues of animal cruelty out of the shadows. We’ve made momentous progress already, but we’re setting our sights even higher. With your help, our 60th anni- 115,851 Animals cared for by The HSUS and versary campaign will raise $60 million, enabling us to create even affiliates this year through cruelty more transformational change for animals. interventions, spay/neuter and vaccination programs, sanctuaries, Although we and our affiliates provide hands-on care and services wildlife rehabilitation and more to more than 100,000 animals every year, our goal has always been to enact change by attacking the root causes of animal cruelty. We target institutions and practices that af- 58,239 fect millions and even billions of animals—like factory farms, puppy Pets spayed or neutered as part mills, inhumane wildlife management programs and animal-testing of World Spay Day labs—and work to become part of the solution. We offer alterna- tives and help develop more humane practices to ensure lasting change. Our staff is comprised of experts in their fields, whose tech- 2.9+ nical knowledge is matched only by their compassion for animals. MILLION Messages that our supporters We’ve done so much already. We’ve made sweeping policy sent to government and corporate and business changes, from making animal cruelty a felony in decision-makers all 50 states (up from just four states in the mid-1980s) to convinc- ing more than 100 major food retailers to remove extreme confine- ment of farm animals from their supply chains. -

(HSVMA) Veterinary Report on Puppy Mills May 2013

Humane Society Veterinary Medical Association (HSVMA) Veterinary Report on Puppy Mills May 2013 Puppy mills are large-scale canine commercial breeding establishments (CBEs) where puppies are produced in large numbers and dogs are kept in inhumane conditions for commercial sale. That is, the dog breeding facility keeps so many dogs that the needs of the breeding dogs and puppies are not met sufficiently to provide a reasonably decent quality of life for all of the animals. Although the conditions in CBEs vary widely in quality, puppy mills are typically operated with an emphasis on profits over animal welfare and the dogs often live in substandard conditions, housed for their entire reproductive lives in cages or runs, provided little to no positive human interaction or other forms of environmental enrichment, and minimal to no veterinary care. This report reviews the following: • What Makes a Breeding Facility a “Puppy Mill”? • How are Puppies from Puppy Mills Sold? • How Many Puppies Come from Puppy Mills? • Mill Environment Impact on Dog Health • Common Ailments of Puppies from Puppy Mills • Impact of Resale Process on Puppy Health • How Puppy Buyers are Affected • Impact on Animal Shelters and Other Organizations • Conclusion • References What Makes a Breeding Facility a “Puppy Mill”? Emphasis on Quantity not Quality Puppy mills focus on quantity rather than quality. That is, they concentrate on producing as many puppies as possible to maximize profits, impacting the quality of the puppies that are produced. This leads to extreme overcrowding, with some CBEs housing 1,000+ dogs (often referred to as “mega mills”). When dogs live in overcrowded conditions, diseases spread easily. -

Veterinary Problems in Puppy Mill Dogs

Veterinary Problems in Puppy Mill Dogs Dogs in puppy mills often suffer from an array of painful and potentially life-shortening veterinary problems due to overcrowded, unsanitary conditions and the lack of proper oversight or veterinary care. Conditions common to puppy mills, such as the use of stacked, wire cages to house more animals than a given space should reasonably hold, as well as constant exposure to the feces and urine of other dogs, make it difficult for dogs to avoid exposure to common parasites and infectious diseases. In addition, a lack of regular, preventive veterinary care, clean food and water, basic cleaning and grooming, and careful daily observation by the operators may cause even minor injuries or infections to fester until they become severe. These disorders cause undue pain and suffering to the animals involved and often result in premature death. TOP : V irgnia ’s state veterina rian determined that this rescued Examples: puppy mill dog suffered from an ulcerated conjunctiva with a pigmented cornea suggestive of long-term eye disease; dental • When 80 dogs were rescued in July 21, 2011 from a puppy disease, dermatitis, and parasites and required emergency mill in Hertford, N.C., a veterinarian with the local intake veterinary care. / VA State Veterinarian report, 2009 SPCA reported that almost 50% of the dogs were afflicted BOTTOM: Skin conditions caused by mites, fleas and secondary with parasites, 23% suffered from ear infections, 15% infections are common in puppy mill dogs due to overcrowding suffered from various eye disorders including KCS, a very and lack of proper care. -

MISSION STATEMENT Global Initiatives Protecting Street Dogs

ANNUAL REPORT 2014 MISSION STATEMENT Humane Society International (HSI) extends the work of The Humane Society of the United States around the globe to promote the human- animal bond, protect street animals, support farm animal welfare, stop wildlife abuse, curtail and eliminate painful animal testing, respond to natural disasters and confront cruelty to animals in all of its forms. cruelty that is supported by government Global Initiatives subsidies. Humane Society International (HSI) When disasters occur, HSI puts a go-team conducts a range of programs together to travel to the stricken nation and internationally that promote the humane address the needs of animals and their management of street animals through human owners in distress. spay/neuter and vaccination programs in Africa, Asia, Latin America, the Pacific and the Caribbean and by ending the dog-meat Protecting Street trade in Asia. HSI seeks a global end to animal testing for human hazard and risk Dogs/Puppy Mills assessment by 2025 and has had HSI is collaborating on efforts to tackle significant success in Europe, India, South rabies, street dog suffering and the illegal America and China. HSI conducts trade in dogs destined for human campaigns to end the use of confinement consumption, amidst mounting concerns for battery cages/gestation crates for chickens human health and animal welfare. The and pigs as well as projects to challenge the commercial trade in dogs for human financing of confinement systems by banks consumption affects an estimated thirty and development agencies. million dogs per year. Street dogs are caught in Thailand, Cambodia and Laos and HSI campaigns against wildlife abuse and illegally transported to Vietnam and China, suffering focus on ending the commercial for slaughter and consumption. -

The Growing Disparity in Protection Between Companion Animals and Agricultural Animals Elizabeth Ann Overcash

NORTH CAROLINA LAW REVIEW Volume 90 | Number 3 Article 7 3-1-2012 Unwarranted Discrepancies in the Advancement of Animal Law:? The Growing Disparity in Protection between Companion Animals and Agricultural Animals Elizabeth Ann Overcash Follow this and additional works at: http://scholarship.law.unc.edu/nclr Part of the Law Commons Recommended Citation Elizabeth A. Overcash, Unwarranted Discrepancies in the Advancement of Animal Law:? The Growing Disparity in Protection between Companion Animals and Agricultural Animals, 90 N.C. L. Rev. 837 (2012). Available at: http://scholarship.law.unc.edu/nclr/vol90/iss3/7 This Comments is brought to you for free and open access by Carolina Law Scholarship Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in North Carolina Law Review by an authorized administrator of Carolina Law Scholarship Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. UNWARRANTED DISCREPANCIES IN THE ADVANCEMENT OF ANIMAL LAW: THE GROWING DISPARITY IN PROTECTION BETWEEN COMPANION ANIMALS AND AGRICULTURAL ANIMALS* INTRO D U CT IO N ....................................................................................... 837 I. SU SIE'S LA W .................................................................................. 839 II. PROGRESSION OF LAWS OVER TIME ......................................... 841 A . Colonial L aw ......................................................................... 842 B . The B ergh E ra........................................................................ 846 C. Modern Cases........................................................................ -

Everything You Didn't Want to Know About the Dog Breeding Industry… …And How We Can Make It Right a FREE Ebook Published B

Everything you didn’t want to know about the dog breeding industry… …And how we can make it right A FREE eBook published by Happy Tails Books Copyright Information: Mill Dog Diaries by Kyla Duffy Published by Happy Tails Books™, LLC http://www.happytailsbooks.com © Copyright 2010 Happy Tails Books™, LLC. This free eBook may be reprinted and distributed but not edited in any way without consent of the publisher. It is the wish of the publisher that you pass this book along to those who may be looking to get a dog or to anyone who simply doesn’t already know this information. Any organization is welcome to use this book as an educational or fundraising tool. If you enjoyed this book, please consider making a donation to dog rescue through http://happytailsbooks.com. Cover photo: Enzo, by Monique and Robert Elardo, It’s the Pits Rescue Author’s Note: The word “he” was used throughout this document for brevity to indicate “he” or “she.” Contents Introduction .................................................................................................................................................. 4 Section1: The Dog Breeding Industry: What Everyone Should Know ........................................................... 5 Puppy Mills and Backyard Breeders .......................................................................................................... 5 A brief comparison of irresponsible and responsible breeders: ............................................................... 5 What are the most common puppy mill breeds? .................................................................................... -

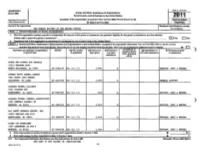

SCHEDULE I OMB No

SCHEDULE I OMB No. 1545-0047 (Form 990) Grants and Other Assistance to Organizations, Governments, and Individuals in the United States 2011 Department of the TreesUl)' Complete if the organization answered "Yes" to Form 990, Part IV, line 21 or 22. Internal Revenue Service ~ Attach to Form 990. Name of the organization Employer identification number THE HUMANE SOCIETY OF THE UNITED STATES 53-0225390 General Information on Grants and Assistance 1 Does the organization maintain records to substantiate the amount of the grants or assistance, the grantees' eligibility for the grants or assistance, and the selection criteria used to award the grants or assistance? ....... .......................................... ................................... .................................... ......................... ................................... 1]:1 Yes DNo 2 Describe in Part IV the or anization's rocedures for monitoTin the use of rant funds in the United States. lJ~a'1: II Grants and Other Assistance to Governments and Organizations in the United States. Complete if the organization answered "Yes" to Form 990, Part IV, line 21, for any recipient that received more than $5,000. Check this box if no one recipient received more than $5,000_ Part II can be duplicated if additional space is needed........................... ~ 0 1 (a) Name and address of organization (b) EIN (c) IRC section (d) Amount of (e) Amount of (~J Memoa OT (g) Description of (h) Purpose of grant ) valuation (book, or govemment if applicable cash grant non-cash non-cash assistance FMV, appraisal, or assistance assistance other) ACTOR AND OTHERS FOR ANIMALS 11523 BURBANK BLVD NORTH HOLLYWOOD, CA 91601 95-2783139 ~01 (e) (3) 2,000, O. SUPPORT: SPAY &: NEUTER AFGHAN STRAY ANIMAL LEAGUE 3823 SOUTH 14TH STREET ARLINGTON, VA 22204 20-2119782 ~01 (e) (3) 3,200, O. -

Read the 2020 Annual Report

2020 Annual Report ACHIEVEMENTS FOR ANIMALS The Humane Society of the United States and Humane Society International work together to end the cruelest practices toward animals, rescue and care for animals in crisis, and build a stronger animal protection movement. And we can’t do it without you. How we work Ending the cruelest practices We are focused on ending the worst forms of institutionalized animal suffering— including extreme confinement of farm animals, puppy mills, the fur industry, trophy hunting, animal testing of cosmetics and the dog meat trade. Our progress is the result of our work with governments, the private sector and multinational bodies; public awareness and consumer education campaigns, public policy efforts, and more. Caring for animals in crisis We respond to large-scale cruelty cases and disasters around the world, providing rescue, hands-on care, logistics and expertise when animals are caught in crises. Our affiliated care centers heal and provide lifelong sanctuary to abused, abandoned, exploited, vulnerable and neglected animals. Building a stronger animal protection movement Through partnerships, trainings, support, collaboration and more, we’re building a more humane world by empowering and expanding the capacity of animal welfare advocates and organizations in the United States and across the globe. Together, we’ll bring about faster change for animals. Our Animal Rescue and Response team stands ready 24/7 to help animals caught in crises in the United States and around the world. Here, HSI director of global animal disaster response Kelly Donithan comforts a koala we saved after the devastating wildfires on Australia’s Kangaroo Island. -

An Advocate's Guide to Stopping Puppy Mills

An Advocate’s Guide to Stopping Puppy Mills An Advocate’s Guide to Stopping Puppy Mills 1 “The greatness of a community is most accurately measured by the compassionate actions of its members.” —CORETTA SCOTT KING 2 An Advocate’s Guide to Stopping Puppy Mills CONTENTS INTRODUCTION..............................................................................................................................3 Why can’t we just ban all puppy mills? ....................................................................................................................3 PART ONE: BECOMING THEIR VOICE .............................................................................................5 Internet and media activism ......................................................................................................................................5 Creative outreach—Classified ads and the public ................................................................................................6 Be heard by lawmakers ...............................................................................................................................................7 Beginner projects ........................................................................................................................................................9 PART TWO: BOOTS ON THE GROUND .........................................................................................13 Puppy friendly pet stores program ..................................................................................................................... -

An Unprecedented Year

An Unprecedented Year SINCE 1954, THE HUMANE SOCIETY OF THE UNITED STATES (HSUS) has worked to create a more humane world through our programs and campaigns, regional offices, and global affiliates. We made an unprecedented leap forward in 2005 by joining with The Fund for Animals, which was founded by the legendary Cleveland Amory in 1967. Combining forces with The Fund represented a significant step toward uniting the entire humane movement in one powerful voice and streamlined our operations, freeing more resources for action on behalf of animals. This historic union also produced the youngest member of our family of organizations—the Humane Society Legislative Fund—and a new section devoted to major campaigns against factory farming, animal fighting and cruelty, the fur industry, and inhumane hunting practices, as well as the nation’s largest in-house animal protection litigation department. The year also saw unprecedented action—a massive mobilization to rescue animals left in the wake of natural disaster—and our staff and members rose to the challenge with unprecedented dedication and generosity. and helped offset costs to allow the sale Helping Pets and Their People of more than 100,000 copies for only 99 cents each. Our Pets for Life® program continued to In close cooperation with several provide a wealth of resources to help Massachusetts organizations, we put our caregivers solve the problems weight heavily behind an initiative to ban that too often separate them greyhound racing, prevent cruelty to service from their pets. We also dogs, and provide stronger penalties for produced new billboards, dogfighters in the state. -

Solving the Problem of Puppy Mills: Why the Animal Welfare Movement's Bark Is Stronger Than Its Bite

Washington University Journal of Law & Policy Volume 43 New Ideas in Law and Legal Education 2014 Solving the Problem of Puppy Mills: Why the Animal Welfare Movement's Bark is Stronger than its Bite Kailey A. Burger Washington University School of Law Follow this and additional works at: https://openscholarship.wustl.edu/law_journal_law_policy Part of the Animal Law Commons Recommended Citation Kailey A. Burger, Solving the Problem of Puppy Mills: Why the Animal Welfare Movement's Bark is Stronger than its Bite, 43 WASH. U. J. L. & POL’Y 259 (2014), https://openscholarship.wustl.edu/law_journal_law_policy/vol43/iss1/14 This Note is brought to you for free and open access by the Law School at Washington University Open Scholarship. It has been accepted for inclusion in Washington University Journal of Law & Policy by an authorized administrator of Washington University Open Scholarship. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Solving the Problem of Puppy Mills: Why the Animal Welfare Movement‘s Bark is Stronger than its Bite Kailey A. Burger I. INTRODUCTION The relationship between man and dog is one characterized by companionship, service, and love; but dogs serve a variety of functions beyond just ―man‘s best friend.‖ These companion animals provide valuable assistance to people with disabilities,1 in military and police service,2 in therapeutic contexts,3 and in numerous other areas of life. With approximately 78.2 million pet dogs in the United States,4 and approximately 39 percent of U.S. households owning at least one dog,5 it is no surprise that so many animal welfare activists and organizations possess a deep passion for protecting and improving the lives of these animals.6 Zuckerman Fellow and Ed.M. -

Encyclopedia of Animal Rights and Animal Welfare

ENCYCLOPEDIA OF ANIMAL RIGHTS AND ANIMAL WELFARE Marc Bekoff Editor Greenwood Press Encyclopedia of Animal Rights and Animal Welfare ENCYCLOPEDIA OF ANIMAL RIGHTS AND ANIMAL WELFARE Edited by Marc Bekoff with Carron A. Meaney Foreword by Jane Goodall Greenwood Press Westport, Connecticut Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Encyclopedia of animal rights and animal welfare / edited by Marc Bekoff with Carron A. Meaney ; foreword by Jane Goodall. p. cm. Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 0–313–29977–3 (alk. paper) 1. Animal rights—Encyclopedias. 2. Animal welfare— Encyclopedias. I. Bekoff, Marc. II. Meaney, Carron A., 1950– . HV4708.E53 1998 179'.3—dc21 97–35098 British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data is available. Copyright ᭧ 1998 by Marc Bekoff and Carron A. Meaney All rights reserved. No portion of this book may be reproduced, by any process or technique, without the express written consent of the publisher. Library of Congress Catalog Card Number: 97–35098 ISBN: 0–313–29977–3 First published in 1998 Greenwood Press, 88 Post Road West, Westport, CT 06881 An imprint of Greenwood Publishing Group, Inc. Printed in the United States of America TM The paper used in this book complies with the Permanent Paper Standard issued by the National Information Standards Organization (Z39.48–1984). 10987654321 Cover Acknowledgments: Photo of chickens courtesy of Joy Mench. Photo of Macaca experimentalis courtesy of Viktor Reinhardt. Photo of Lyndon B. Johnson courtesy of the Lyndon Baines Johnson Presidential Library Archives. Contents Foreword by Jane Goodall vii Preface xi Introduction xiii Chronology xvii The Encyclopedia 1 Appendix: Resources on Animal Welfare and Humane Education 383 Sources 407 Index 415 About the Editors and Contributors 437 Foreword It is an honor for me to contribute a foreword to this unique, informative, and exciting volume.