Team Mascot Antics Not Assumed Spectator Risk

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

GAME NOTES Tuesday, May 11, 2021

GAME NOTES Tuesday, May 11, 2021 2019 PCL Pacific Southern Division Champions Game 6 – Home Game 6 Sacramento River Cats (2-3) (AAA-S.F. Giants) vs. Las Vegas Reyes de Plata (3-2) (AAA-Oakland Athletics) Aviators At A Glance . The Series (L.V. leads 3-2) Overall Record: 3-2 (.600) Home: 3-2 (.600) PROBABLE STARTING PITCHERS Road: 0-0 (.000) Day Games: 1-0 (1.000) SACRAMENTO LAS VEGAS Tues. (7:05) – LHP Anthony Banda (1-0, 0.00) RHP Matt Milburn 0-0, 0.00) Night Games: 2-2 (.500) Wednesday, May 12 OFF DAY Follow the Aviators on Facebook/Las Vegas Aviators Baseball Team & Twitter/@AviatorsLV Probable Starting Pitchers (Las Vegas at Reno, May 13-18) RENO LAS VEGAS Thurs. (6:35) – TBA RHP Parker Dunshee (0-1, 13.50) Radio: KRLV AM 920 - Russ Langer Fri. (6:35) – TBA RHP Grant Holmes (0-0, 15.00) Web & TV: www.aviatorslv.com; MiLB.TV Sat. (4:05) – TBA RHP Paul Blackburn (0-0. 5.40) Aviators vs. River Cats: The Las Vegas Reyes de Plata professional baseball team, Triple-A affiliate of the Oakland Athletics, will host the Sacramento River Cats, Triple-A affiliate of the San Francisco Giants, tonight in the finale of the season -opening six-game series in Triple-A West action at Las Vegas Ballpark (8,834)…Las Vegas is 3-2 on the homestand…following an off day on Wednesday, May 12, Las Vegas will embark on its first road trip of the season to Northern Nevada to face intrastate rival, the Reno Aces, Triple-A affiliate of the Arizona Diamondbacks, in a six-game series at Greater Nevada Field from Thursday-Tuesday, May 13-18. -

Seattle Area Baseball Umpire Camp

Seattle Area Baseball Umpire Camp February 8th, 2020 - 8:00am-4:00pm Everett Memorial Stadium • A one-day camp featuring current Major League, Minor League, and college umpires. • Tailored for umpires of all levels. • Includes indoor instruction, cage training, and field training. • Provides training credit for local area associations. Little League High School Sub-Varsity High School Varsity Apprentice B Tier Connie Mack C Tier A Tier High School C-Games Tournament Tier Introduction Introduction Introduction 8:00am-8:30am Everett Stadium Conference Everett Stadium Conference Everett Stadium Conference Center Center Center Orientation to Umpiring Everett Stadium Cages Field Training Everett Stadium 8:30am-10-30am Field Training Everett Stadium Conference Everett Stadium Cages Everett Stadium Center Taking the Next Step 10:30am-12:30pm 12:30pm-1:30pm LUNCH at Everett Stadium Conference Everett Stadium Cages Field Training Mistakes even the best make Everett StadiumCenter Everett Stadium Conference Center 1:30pm-3:30pm Finale Finale Finale 3:30pm-4:00pm Everett Stadium Conference Everett Stadium Conference Everett Stadium Conference Center Center Center NOTES: • Umpire support: • Tripp Gibson – Major League Umpire • Mike Muchlinski – Major League Umpire • Brian Hertzog – NCAA Div I & Div II Umpire • Jacob Metz – Minor League Umpire • Cage Training and Field Training support from College–level umpires from NBUA and SCBUA • Uniform: wear the uniform for the bases/field. Plate gear will be worn over the field uniform when in the cages. • Lunch will be provided: sub-sandwiches, chips, water, soda • Cost: $15.00 (assessed at the end of the 2020 season) This covers the cost of the trainers and the food. -

Minor League Presidents

MINOR LEAGUE PRESIDENTS compiled by Tony Baseballs www.minorleaguebaseballs.com This document deals only with professional minor leagues (both independent and those affiliated with Major League Baseball) since the foundation of the National Association of Professional Baseball Leagues (popularly known as Minor League Baseball, or MiLB) in 1902. Collegiate Summer leagues, semi-pro leagues, and all other non-professional leagues are excluded, but encouraged! The information herein was compiled from several sources including the Encyclopedia of Minor League Baseball (2nd Ed.), Baseball Reference.com, Wikipedia, official league websites (most of which can be found under the umbrella of milb.com), and a great source for defunct leagues, Indy League Graveyard. I have no copyright on anything here, it's all public information, but it's never all been in one place before, in this layout. Copyrights belong to their respective owners, including but not limited to MLB, MiLB, and the independent leagues. The first section will list active leagues. Some have historical predecessors that will be found in the next section. LEAGUE ASSOCIATIONS The modern minor league system traces its roots to the formation of the National Association of Professional Baseball Leagues (NAPBL) in 1902, an umbrella organization that established league classifications and a salary structure in an agreement with Major League Baseball. The group simplified the name to “Minor League Baseball” in 1999. MINOR LEAGUE BASEBALL Patrick Powers, 1901 – 1909 Michael Sexton, 1910 – 1932 -

The Mirage of SAPA & Minor League Baseball Wages

BRUCKER (DO NOT DELETE) 11/5/2020 10:25 PM [SCREW] AMERICA’S PASTIME ACT: THE MIRAGE OF SAPA & MINOR LEAGUE BASEBALL WAGES John Brucker* I. INTRODUCTION The dream of becoming a professional baseball player is an aspiration as all-American as the sport itself. And while baseball and hot dogs are a timeless duo, it is unsurprising that few young people are as enchanted by the prospect of becoming a professional hot dog vendor. Curiously, though, in all but a select few professional ballparks, the hot dog vendor actually makes more money than the ballplayer.1 Jeremy Wolf, a minor league baseball player formerly in the New York Mets organization, attests, “I was paid $45 per game . $3 [per] hour for 70 hours a week . I played in front of 8,000 people [each] night and went to bed hungry. [A]fter seven months of work, I left with less money than I started . .”2 Be that as it may, Major League Baseball (MLB), for its part, presides over this puzzling reality as puppeteer.3 Players at the MLB level earn astounding wealth; however, members of a major league team’s minor leagues—the multi-tiered system below it that employs thousands of Minor League Baseball (MiLB) players who form the lifeblood of an organization’s future—fight to pay rent and eat a decent meal, all while vying rigorously for a promotion to MLB. Because of the inherent symbiosis between MLB and MiLB, the wage disparity between the two entities defies common sense, but not logic: MLB is a business and a good one at that. -

SABR Minor League Newsletter ------Robert C

SABR Minor League Newsletter --------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------- Robert C. "Bob" McConnell, Chairman 210 West Crest Road Wilmington DE 19803 ReedHoward November 2000 (302) 764-4806 [email protected] --------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------- Joe Overfield Most of you read about the death of Joe Overfield in the September-October SABR newsletter. Joe was one of our top minor league researchers and he was always willing to help others with their research. We will miss Joe. 1937 Bi-State and Coastal Plain Leagues Ray Nemec is compiling averages for the 1937 Bi-State and Coastal Plain Leagues. He needs the following box scores: Bi-StateSept. 3 Martinsville11 South Boston 9 Coastal Plain May 14 Greenville 8 Snow Hill 9 May 18 Snow Hill 11 Aydon 6 May 19 Snow Hill 8 Aydon 4 May 23 New Bern 0 Snow Hill 12 May 25 Aydon 5 Snow Hill 3 May 26 Aydon 7 Snow Hill 9 May 27 Williamson 3 Snow Hill 7 May 28 Williamson 8 Snow Hill 6 Kitty League Kevin McCann is working on a history of the Kitty League. In addition he is compiling averages for the 1903-05 and 1922-24 seasons, as well as redoing the 1935 season. Kevin is experiencing long waits in obtaining newspaper microfilm via the inter-library loan. If you have access to any newspapers in the following cities, please contact Kevin at 283 Murrell Road, Dickson, TN 37055, or [email protected]: Bowling Green, KY 1939-41 McLeansboro, IL 1910-11 Cairo, -

2012 Information Guide

2012 INFORMATION GUIDE Mesa Peoria Phoenix Salt River Scottsdale Surprise Solar Sox Javelinas Desert Dogs Rafters Scorpions Saguaros BRYCE HARPER INTRODUCING THE UA SPINE HIGHLIGHT SUPER-HIGH. RIDICULOUSLY LIGHT. This season, Bryce Harper put everyone on notice while wearing the most innovative baseball cleats ever made. Stable, supportive, and shockingly light, they deliver the speed and power that will define the legends of this generation. Under Armour® has officially changed the game. Again. AVAILABLE 11.1.12 OFFICIAL PERFORMANCE Major League Baseball trademarks and copyrights are used with permission ® of Major League Baseball Properties, Inc. Visit MLB.com FOOTWEAR SUPPLIER OF MLB E_02_Ad_Arizona.indd 1 10/3/12 2:27 PM CONTENTS Inside Q & A .......................................2-5 Organizational Assignments ......3 Fall League Staff .........................5 Arizona Fall League Schedules ................................6-7 Through The Years Umpires .....................................7 Diamondbacks Saguaros Lists.......................................8-16 Chandler . 1992–94 Peoria.................2003–10 Desert Dogs Phoenix ...................1992 Top 100 Prospects ....................11 Mesa . .2003 Maryvale............1998–2002 Player Notebook ..................17-29 Phoenix ..... 1995–2002, ’04–11 Mesa . .1993–97 Mesa Solar Sox ....................31-48 Javelinas Surprise...................2011 Peoria Javelinas ...................49-66 Tucson . 1992–93 Scorpions Peoria...............1994–2011 Scottsdale . 1992–2004, ’06–11 -

APPENDIX TABLE of APPENDICES Appendix a Opinion, United States Court of Appeals for the Ninth Circuit, Senne V

APPENDIX TABLE OF APPENDICES Appendix A Opinion, United States Court of Appeals for the Ninth Circuit, Senne v. Kansas City Royals Baseball Corp., Nos. 17-16245, 17-16267, 17-16276 (Aug. 16, 2019) ............................................. App-1 Appendix B Order, United States Court of Appeals for the Ninth Circuit, Senne v. Kansas City Royals Baseball Corp., Nos. 17-16245, 17-16267, 17-16276 (Jan. 3, 2020) ............................................. App-90 Appendix C Order, United States District Court for the Northern District of California, Senne v. Kansas City Royals Baseball Corp., No. 14-cv-00608-JCS (Mar. 7, 2017) ......... App-92 App-1 Appendix A UNITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS FOR THE NINTH CIRCUIT ________________ Nos. 17-16245, 17-16267, 17-16276 ________________ AARON SENNE, et al., Plaintiffs-Appellants, v. KANSAS CITY ROYALS BASEBALL CORP., et al., Defendants-Appellees. ________________ Argued: June 13, 2018 Filed: Aug. 16, 2019 ________________ Before: Michael R. Murphy,* Richard A. Paez, and Sandra S. Ikuta, Circuit Judges. ________________ OPINION ________________ PAEZ, Circuit Judge: It is often said that baseball is America’s pastime. In this case, current and former minor league baseball players allege that the American tradition of baseball collides with a tradition far less benign: the * The Honorable Michael R. Murphy, United States Circuit Judge for the U.S. Court of Appeals for the Tenth Circuit, sitting by designation. App-2 exploitation of workers. We are tasked with deciding whether these minor league players may properly bring their wage-and-hour claims on a collective and classwide basis. BACKGROUND I. Most major professional sports in America have their own “farm system” for developing talent: for the National Basketball Association, it’s the G-League; for the National Hockey League, it’s the American Hockey League; and for Major League Baseball (MLB), it’s Minor League Baseball. -

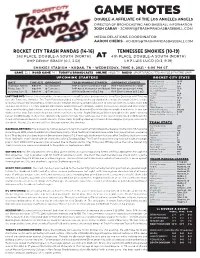

Game Notes Double-A Affiliate of the Los Angeles Angels Director of Broadcasting and Baseball Information: Josh Caray - [email protected]

GAME NOTES DOUBLE-A AFFILIATE OF THE LOS ANGELES ANGELS DIRECTOR OF BROADCASTING AND BASEBALL INFORMATION: JOSH CARAY - [email protected] MEDIA RELATIONS COORDINATOR: AARON CHERIS - [email protected] ROCKET CITY TRASH PANDAS (14-16) TENNESSEE SMOKIES (10-19) 3rd PLACE, DOUBLE-A SOUTH (NORTH) AT 4th PLACE, DOUBLE-A SOUTH (NORTH) RHP DENNY BRADY (0-1, 3.52) LHP LUIS LUGO (0-3, 9.19) SMOKIES STADIUM - KODAK, TN - WEDNESDAY, JUNE 9, 2021 - 6:00 PM CT GAME 32 | ROAD GAME 14 | TODAY’S BROADCASTS ONLINE MiLB TV RADIO SPORTSRADIO 730 AM/103.9 FM THE UMP UPCOMING STARTERS ROCKET CITY STATS Overall Record ....................... 14-16 DATE TIME (CT) OPPONENT TRASH PANDAS STARTER OPPONENT STARTER Home Record ......................... 10-7 Thursday, June 10 6:00 PM @ Tennessee RHP Cooper Criswell (2-3, 4.00) RHP Peyton Remy (0-1, 0.00) Road Record ........................... 4-9 Friday, June 11 6:00 PM @ Tennessee RHP Aaron Hernandez (AA Debut) RHP Cam Sanders (0-1, 4.40) vs. North Division .................. 13-11 Saturday, June 12 6:00 PM @ Tennessee LHP Reid Detmers (1-2, 3.60) RHP Erich Uelman (0-3, 5.06) vs. South Division .................. 1-5 vs RHP .......................................... 10-9 LAST TIME OUT: Rocket City clocked three homers and received 3.1 perfect innings of relief from Tyler Danish in an 8-7 victory vs LHP .......................................... 4-7 Night ............................................ 13-13 over the Tennessee Smokies. The Trash Pandas pounded out 14 hits as the top third of the lineup, shortstop Gavin Cecchini, Day ................................................. 1-4 designated hitter Dalton Pompey, and leftfielder Orlando Martinez combined to go 8-14 with two homers, a triple, three RBI Last 10 ......................................... -

Danville High School Baseball Alumni

Danville High School Baseball Alumni DHS Alumni in College Baseball Programs 2012 Cash Kiser Culver- Stockton 2011 Cody Burton Lakeland 2010 2009 Tyler Burton Oakton Chadd Snyder CC MacMurray 2008 Ty Montgomery Brandon Jones DACC DACC 2007 Jacob Jurczak DACC/Blackburn 2006 David Worthington Avion Forthenberry Dante Baxter DACC/Southern DACC/ MacMurray MacMurray University 2005 Ben Wolgamot Kyleer Vance Aaron Forthenberry DACC/Purdue DACC DACC/ MacMurray 2004 Tyler Brandon Derek Bullias Parkland/Eastern DACC/Blackburn Illinois 2003 Cailub Pounds Jordan Powell Jason Lucas DACC DACC/Southern Ill./ Triton/UIC Houston Astros 2002 Cole Graham Cole Smalley Kody Strebin Jason Krainock Justin Strader Triton/Houston DACC DACC DACC DACC Astros 2001 Geoff Desmond DACC/Arkansas St. 2000 Gene Oliver Adam Steht Rigo Torres Ryan Graham Eastern Illinois DACC DACC Triton/Delaware University 1999 Kirk Strebin Adam Joslin Blake Leibach DACC/UNC DACC DACC Greensboro 1998 John Clem Aaron Evans DACC/Southern DACC Illinois Unversity 1997 Jason Anderson Nick Steht University Of Triton/Memphis Illinois/ Chicago Cubs Click here to see pictures of Anderson's professional career 1996 1995 Justin Kees Mike Palmer Todd Thomas DACC/Southern DACC University of Illinois Louisville University/Rockford Riverhawks (Independant) 1994 Adam Decker DACC 1993 1992 1991 Andy Schofield Andy Kortkamp Illinois State University of Illinois University Back to Top Vikings in Professional Baseball Student Year Graduated Pro Team Powell, Jordan 2003 Houston Astros Graham, Cole 2002 Houston Astros Desmond, Geoff 2001 St. Louis Cardinals Graham, Ryan 2000 Houston Astros Anderson, Jason 1997 Philadelphia Phillies Back to Top A great article from the Baton Rouge Advocate on the perseverance of Southern University Senior and former Danville Viking slugger David Worthington. -

2019 Cal League Executive Awards

MEDIA INFORMATION California Professional Baseball League 3600 South Harbor Blvd. #122 / Oxnard, CA 93035 www.CaliforniaLeague.com | Twitter: @CalLeague1 | Facebook: California League of Professional Baseball For Immediate Release Matt Blaney September 19, 2019 [email protected] 805-985-8585 2019 Cal League Executive Awards Oxnard, CA – The California League is proud to announce its Executive Awards for the 2019 season. Teams submitted nominations and winners were voted on by their peers. Organization of the Year: The San Jose Giants – The Giants will represent the Cal League for the national John H. Johnson President’s Award. The award is given annually to a club in Minor League Baseball. The San Jose Giants had a tremendous season. For the first time in franchise history, the club secured a naming rights deal with Excite Credit Union. The organization also set a franchise record in sponsorships. A marketing push to capitalize on two top prospects, Helliot Ramos and Joey Bart, helped increase attendance and ticket revenue. After a several year decline, the organization is averaged 210 fans more per game than last season, a 9.7% increase in attendance year- to-date. The Giants continued their excellent work in the Community. The front office, players and mascot will have made more than 225 appearances across the surrounding communities in 2019. The organization agreed to a partnership with Kaiser Permanente to launch the #WeCareWednesday program, which focused on non-profits serving underserved communities and providing them tickets, tabling and on-field presentations every Wednesday game. On the heels of the Cal League’s successful efforts to raise funds for victims of wildfires, which generated $7,297 for the North Division, the Giants partnered with Walmart to co-sponsor our First Responder’s Night to raise additional revenue for the Camp Fire victims. -

Senne V. Kansas City Royals Baseball

FOR PUBLICATION UNITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS FOR THE NINTH CIRCUIT AARON SENNE; MICHAEL LIBERTO; Nos. 17-16245 OLIVER ODLE; BRAD MCATEE; CRAIG 17-16267 BENNIGSON; MATT LAWSON; KYLE 17-16276 WOODRUFF; RYAN KIEL; KYLE NICHOLSON; BRAD STONE; MATT D.C. No. DALY; AARON MEADE; JUSTIN 3:14-cv-00608- MURRAY; JAKE KAHAULELIO; RYAN JCS KHOURY; DUSTIN PEASE; JEFF NADEAU; JON GASTON; BRANDON HENDERSON; TIM PAHUTA; LEE OPINION SMITH; JOSEPH NEWBY; RYAN HUTSON; MATT FREVERT; ROBERTO ORTIZ; WITER JIMENEZ; KRIS WATTS; MITCH HILLIGOSS; DANIEL BRITT; YADEL MARTI; HELDER VELAQUEZ; JORGE JIMENEZ; JORGE MINYETY; EDWIN MAYSONET; JOSE DIAZ; NICK GIARRAPUTO; LAUREN GAGNIER; LEONARD DAVIS; GASPAR SANTIAGO; GRANT DUFF; OMAR AGUILAR; MARK WAGNER; DAVID QUINOWSKI; BRANDON PINCKNEY, Individually and on Behalf of All Those Similarly Situated; JAKE OPITZ; BRETT NEWSOME, Plaintiffs-Appellants, v. 2 SENNE V. KANSAS CITY ROYALS BASEBALL KANSAS CITY ROYALS BASEBALL CORP.; MARLINS TEAMCO LLC; SAN FRANCISCO BASEBALL ASSOCIATES, LLC; OFFICE OF THE COMMISSIONER OF BASEBALL, DBA Major League Baseball, an unincorporated association; ALLAN HUBER SELIG, “BUD”; ANGELS BASEBALL LP; ST. LOUIS CARDINALS, LLC; COLORADO ROCKIES BASEBALL CLUB, LTD.; CINCINNATI REDS, LLC; HOUSTON BASEBALL PARTNERS LLC; ATHLETICS INVESTMENT GROUP, LLC; ROGERS BLUE JAYS BASEBALL PARTNERSHIP; PADRES L.P.; SAN DIEGO PADRES BASEBALL CLUB, L.P.; MINNESOTA TWINS, LLC; DETROIT TIGERS, INC.; LOS ANGELES DODGERS LLC; STERLING METS L.P.; AZPB L.P.; NEW YORK YANKEES P’SHIP; RANGERS BASEBALL EXPRESS, LLC; MILWAUKEE BREWERS BASEBALL CLUB, INC.; CHICAGO CUBS BASEBALL CLUB, LLC; PITTSBURGH ASSOCIATES, LP; BASEBALL CLUB OF SEATTLE, LLP; LOS ANGELES DODGERS HOLDING COMPANY LLC; RANGERS BASEBALL, LLC, Defendants-Appellees. -

East Kernapril 2017 Eastvisionsvisions Kern East Kernapril 2017 Eastvisionsvisions Kern

The desert is blooming! Find the best spots to work out your camera. PAGE 3 East KernApril 2017 EastVisionsVisions Kern East KernApril 2017 EastVisionsVisions Kern Inside this issue Plenty of petals to photograph ...................................................................... 3 Four simple rules for getting good shots ...................................................... 6 Local racer wins hometown event ................................................................ 7 Touch base with Cal City’s new Pecos League team ................................... 9 Publisher Fairgrounds become the hub for local events ............................................ 11 John Watkins Concert in the Rocks .................................................................................... 13 Editor Cruise on over to these car shows .............................................................. 14 Aaron Crutchfield ON THE COVER: Advertising Director A bee searches for pollen Paula McKay among the inviting yellow flowers in Short Canyon. Advertising Sales Rodney Preul STORY, PAGE 3 Gerald Elford Robert Aslanian Writers Jack Barnwell Michael Smit Christopher Livingston Jim Matthews MICHAEL SMIT/DAILY INDEPENDENT 2 APRIL 2017 EAST KERN VISIONS The desert is blooming ... here’s where MICHAEL SMIT/DAILY INDEPENDENT Yellow and purple flowers break in to add variety to the yellow fields of coreopsis flowers in Short Canyon. BY MICHAEL SMIT The Daily Independent fter years of drought that left Southern California dry and forced the implementation of new