Jahrbuch Des Simon-Dubnow-Instituts

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Rabbi Stephen S. Wise, Ph.D. and the Rise of Social Jewish Progressivism in Portland, Or, 1900-1906

Portland State University PDXScholar Dissertations and Theses Dissertations and Theses 1-1-2010 A Rabbi in the Progressive Era: Rabbi Stephen S. Wise, Ph.D. and the Rise of Social Jewish Progressivism in Portland, Or, 1900-1906 Mordechai Ben Massart Portland State University Follow this and additional works at: https://pdxscholar.library.pdx.edu/open_access_etds Let us know how access to this document benefits ou.y Recommended Citation Massart, Mordechai Ben, "A Rabbi in the Progressive Era: Rabbi Stephen S. Wise, Ph.D. and the Rise of Social Jewish Progressivism in Portland, Or, 1900-1906" (2010). Dissertations and Theses. Paper 729. https://doi.org/10.15760/etd.729 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access. It has been accepted for inclusion in Dissertations and Theses by an authorized administrator of PDXScholar. Please contact us if we can make this document more accessible: [email protected]. A Rabbi in the Progressive Era: Rabbi Stephen S. Wise, Ph.D. and the Rise of Social Jewish Progressivism in Portland, Or, 1900-1906 by Mordechai Ben Massart A thesis in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in History Thesis Committee: David A. Horowitz Ken Ruoff Friedrich Schuler Michael Weingrad Portland State University 2010 ABSTRACT Rabbi Stephen S. Wise presents an excellent subject for the study of Jewish social progressivism in Portland in the early years of the twentieth-century. While Wise demonstrated a commitment to social justice before, during, and after his Portland years, it is during his ministry at congregation Beth Israel that he developed a full-fledged social program that was unique and remarkable by reaching out not only within his congregation but more importantly, by engaging the Christian community of Portland in interfaith activities. -

Mattos Chassidus on the Massei ~ Mattos Chassidus on the Parsha +

LIGHTS OF OUR RIGHTEOUS TZADDIKIM בעזרת ה ' יתבר A Tzaddik, or righteous person , makes everyone else appear righteous before Hashem by advocating for them and finding their merits. Kedushas Levi, Parshas Noach (Bereishis 7:1) MATTOS ~ MASSEI _ CHASSIDUS ON THE PARSHA + Dvar Torah – Mattos Keep Your Word The Torah states (30:3), “If a man takes a vow or swears an oath to G -d to establish a prohibition upon himself, he shall not violate his word; he shall fulfill whatever comes out of his mouth.” In relation to this passuk , the Midrash quotes from Tehillim (144:4), “Our days are like a fleeting shadow.” What is the connection? This can be explained, says Rav Levi Yitzchok, according to a Gemara ( Nedarim 10b), which states, “It is forbidden to say, ‘ Lashem korban , for G-d − an offering.’ Instead a person must say, ‘ Korban Lashem , an offering for G -d.’ Why? Because he may die before he says the word korban , and then he will have said the holy Name in vain.” In this light, we can understand the Midrash. The Torah states that a person makes “a vow to G-d.” This i s the exact language that must be used, mentioning the vow first. Why? Because “our days are like a fleeting shadow,” and there is always the possibility that he may die before he finishes his vow and he will have uttered the Name in vain. n Story The wood chopper had come to Ryczywohl from the nearby village in which he lived, hoping to find some kind of employment. -

אוסף מרמורשטיין the Marmorstein Collection

אוסף מרמורשטיין The Marmorstein Collection Brad Sabin Hill THE JOHN RYLANDS LIBRARY UNIVERSITY OF MANCHESTER Manchester 2017 1 The Marmorstein Collection CONTENTS Acknowledgements Note on Bibliographic Citations I. Preface: Hebraica and Judaica in the Rylands -Hebrew and Samaritan Manuscripts: Crawford, Gaster -Printed Books: Spencer Incunabula; Abramsky Haskalah Collection; Teltscher Collection; Miscellaneous Collections; Marmorstein Collection II. Dr Arthur Marmorstein and His Library -Life and Writings of a Scholar and Bibliographer -A Rabbinic Literary Family: Antecedents and Relations -Marmorstein’s Library III. Hebraica -Literary Periods and Subjects -History of Hebrew Printing -Hebrew Printed Books in the Marmorstein Collection --16th century --17th century --18th century --19th century --20th century -Art of the Hebrew Book -Jewish Languages (Aramaic, Judeo-Arabic, Yiddish, Others) IV. Non-Hebraica -Greek and Latin -German -Anglo-Judaica -Hungarian -French and Italian -Other Languages 2 V. Genres and Subjects Hebraica and Judaica -Bible, Commentaries, Homiletics -Mishnah, Talmud, Midrash, Rabbinic Literature -Responsa -Law Codes and Custumals -Philosophy and Ethics -Kabbalah and Mysticism -Liturgy and Liturgical Poetry -Sephardic, Oriental, Non-Ashkenazic Literature -Sects, Branches, Movements -Sex, Marital Laws, Women -History and Geography -Belles-Lettres -Sciences, Mathematics, Medicine -Philology and Lexicography -Christian Hebraism -Jewish-Christian and Jewish-Muslim Relations -Jewish and non-Jewish Intercultural Influences -

A Taste of Torah

Parshas Bo January 11, 2019 A Taste of Torah Stories for the Soul G-d in the Details by Rabbi Chaim Yeshia Freeman Scroll Down This week’s parsha discusses the final properly express our gratitude to Baron Shimon Wolf Rothschild, three plagues that Hashem brought Hashem. For instance, when we recite of the famed Rothschild family, upon the Egyptians, culminating in a blessing over bread, we should try to wanted a Torah scroll written for him, as per the commandment in the Exodus from Egypt. This event think about the numerous details of the Torah that a Jew should write plays a major role in our lives, as we the natural world that are necessary his own Torah scroll. He searched are commanded in numerous mitzvos to create a loaf of bread. Rabbi Yisroel for a sofer who would live up to the to remember the Exodus. Typically, Salanter (1809-1883) adds another high standards of piety he wanted we commemorate the general concept dimension with a parable of someone imbued in his Torah scroll. Finally, of the Exodus on a daily basis. Once eating in a high-end restaurant. The he found a sofer who enjoyed an a year, however, on Pesach, we are exorbitant prices are not due only excellent reputation, and hired obligated to retell the complete story to the food, but also include the him to write the Torah scroll. in detail. elegant décor, the relaxed ambiance, After many months, the sofer came When Moshe commands the Jewish the beautiful music playing in the to tell the Baron that the scroll People to remember the Exodus, he background. -

Bal Tashchit : the Jewish Prohibition Against Needless Destruction Wolff, K.A

Bal Tashchit : the Jewish prohibition against needless destruction Wolff, K.A. Citation Wolff, K. A. (2009, December 1). Bal Tashchit : the Jewish prohibition against needless destruction. Retrieved from https://hdl.handle.net/1887/14448 Version: Corrected Publisher’s Version Licence agreement concerning inclusion of doctoral thesis in the License: Institutional Repository of the University of Leiden Downloaded from: https://hdl.handle.net/1887/14448 Note: To cite this publication please use the final published version (if applicable). BAL TASHCHIT: THE JEWISH PROHIBITION AGAINST NEEDLESS DESTRUCTION Copyright © 2009 by K. A. Wolff All rights reserved Printed in Jerusalem BAL TASHCHIT: THE JEWISH PROHIBITION AGAINST NEEDLESS DESTRUCTION Proefschrift ter verkrijging van de graad van Doctor aan de Universiteit Leiden, op gezag van de Rector Magnificus prof. mr P.F. van der Heijden, volgens besluit van het College voor Promoties te verdedigen op dinsdag 1 december 2009 klokke 15:00 uur door Keith A. Wolff geboren te Fort Lauderdale (Verenigde Staten) in 1957 Promotiecommissie Promotores: Prof. Dr F.A. de Wolff Prof. Dr A. Wijler, Rabbijn, Jerusalem College of Technology Overige leden: Prof. Dr J.J. Boersema, Vrije Universiteit Amsterdam Prof. Dr A. Ellian Prof. Dr R.W. Munk, Vrije Universiteit Amsterdam Prof. Dr I.E. Zwiep, Universiteit van Amsterdam To my wife, our children, and our parents Preface This is an interdisciplinary thesis. The second and third chapters focus on classic Jewish texts, commentary and legal responsa, including the original Hebrew and Aramaic, along with translations into English. The remainder of the thesis seeks to integrate principles derived from these Jewish sources with contemporary Western thought, particularly on what might be called 'environmental' themes. -

Tzadik Righteous One", Pl

Tzadik righteous one", pl. tzadikim [tsadi" , צדיק :Tzadik/Zadik/Sadiq [tsaˈdik] (Hebrew ,ṣadiqim) is a title in Judaism given to people considered righteous צדיקים [kimˈ such as Biblical figures and later spiritual masters. The root of the word ṣadiq, is ṣ-d- tzedek), which means "justice" or "righteousness". The feminine term for a צדק) q righteous person is tzadeikes/tzaddeket. Tzadik is also the root of the word tzedakah ('charity', literally 'righteousness'). The term tzadik "righteous", and its associated meanings, developed in Rabbinic thought from its Talmudic contrast with hasid ("pious" honorific), to its exploration in Ethical literature, and its esoteric spiritualisation in Kabbalah. Since the late 17th century, in Hasidic Judaism, the institution of the mystical tzadik as a divine channel assumed central importance, combining popularization of (hands- on) Jewish mysticism with social movement for the first time.[1] Adapting former Kabbalistic theosophical terminology, Hasidic thought internalised mystical Joseph interprets Pharaoh's Dream experience, emphasising deveikut attachment to its Rebbe leadership, who embody (Genesis 41:15–41). Of the Biblical and channel the Divine flow of blessing to the world.[2] figures in Judaism, Yosef is customarily called the Tzadik. Where the Patriarchs lived supernally as shepherds, the quality of righteousness contrasts most in Contents Joseph's holiness amidst foreign worldliness. In Kabbalah, Joseph Etymology embodies the Sephirah of Yesod, The nature of the Tzadik the lower descending -

Memorial Books As Sources for Family History

MEMORIAL BOOKS AS SOURCES FOR FAMILY HISTORY Zachary M. Baker INTROVUCTION ly preceding World War II.3 Taken as a body of As a librarian active in the genealogical literature, they also stand out as "the foremost field, I frequently receive inquiries about memo- source for ethnographic material on traditional rial (yizkor) books. The~e~inquiriesall too of- Jewish life," as an anthropologist who has used ten reveal a host of mistaken impressions that them extensively in his research has remarked.4 people share, about the very nature of yizkor Many -- but not fi -- yizkor books do in- books and the ways in which they can be used by clude lists of names of Holocaust victims as sup- the genealogist. In this article I will try to plements, which< is very much in keeping with correct some of these misconceptions, provide a their function as Holocaust documents. Usually description of the bookst contents and their de- these lists are in Hebrew or Yiddish. (In rare velopment as a genre, and suggest the uses to cases, these Holocaust necrologies do appear in which they can most practically be put, in the the Roman alphabet.) They are often incomplete, service of family history. For reasons that are reflecting only those names known to survivors. explained in the preface to the accompanying bib- Books for smaller communities are likely to have liography of memorial books, I have arbitrarily fuller lists than are books for larger communi- limited my discussion to memorial books for Eat- ties. It is simply much easier to document the W European Jewish communities. -

Ancient Commitments In

Rabbi David Keleti was an accomplished maggid shiur in Israel when he discovered he had another mission. A native of Hungary and fluent in its language, he left his family behind and set The cannons no longer blast from atop Dobo Square. In fact, this historic plaza has just undergone a dramatic off to sustain the trickle of Jews 21st-century facelift. But as I stand here, at the foot of the whose identities were reemerging ancient fort of Eger — a 500-year-old castle and monument to patriotic heroism in Hungary — I can almost hear the from decades of persecution and desperate cannon fire in our imaginations. The fortress has known regional wars, bloody battles, and passionate neglect. Would he succeed? We revolutions, although now the artillery barrels stand empty, spent a Shabbos there to find out dusty, and abandoned. A bit like the Jewish community that once thrived here. Eger — known as Erloi by the Jews (spelled Erlau by the Germans) — is famous for its ancient battles, but also for its hot springs and world-class wines, about which Rebbe Na- chman of Breslov said that anyone who tastes Hungarian wine can never go back to the taste of other wine. There is no kosher Hungarian wine, though; during my Shabbos in Eger, I made Kiddush on American grape juice. CommitmentsNew in Ancient BY Aryeh Ehrlich, Hungary PHOTOS Avinoam Yogav Eger 76 MISHPACHA 20 Adar 5775 | March 11, 2015 MISHPACHA 77 New Commitments in Ancient Eger 70 YEARS EMPTY “There are 90,000 Jews in Budapest alone, yet most of them don’t even know what Ancient Eger, contested by the Turks and then the Habsburgs, always seemed to bounce For the few Judaism is.” Rabbi Keleti is trying to Today there are approximately 90,000 Jews back from calamity. -

Aug 2009 Newsletter

York County Jewish Community News AUGUST 2009/AV 5769 WWW.ETZCHAIMME.ORG PO BOX 905 KENNEBUNK, ME 04043 L’Shanah Tovah: Welcoming in 5770 Please join us for High Holiday Alan Fink will chant Torah and services this year. Cantor Scott the haftarahs will be chanted by Rapaport will be traveling from several of our Hebrew School alumni Bangor to Biddeford to lead services. and teachers. Our newest readers will Rumor has it that his family will join be Silas Phipps-Costin and Beniam As the Torah covers go him, so we will have a chance to Hollman, who will share the Yom from dark to white, w e l c o m e P a t t i , S a m & B e n . Kippur afternoon haftarah, the familiar So may our motives Tashlich will be on the second (and very, very, very long) story of and our actions day of Rosh Hashanah, because the J o n a h a n d t h e W h a l e . Change from greed first day is Shabbat. At the end of the David Strassler will lead his to generosity, Musaf service (around 12 or 12:30) we famous Family Services on the first will walk down the hill to throw our day of Rosh Hashanah and on Yom From selfishness sins (breadcrumbs) into the Saco Kippur. The services are meaningful to compassion, River. This meaningful tradition really for family members of all ages. From fear to faith, gives the feeling of the fresh start of Our Community Break Fast is And from indifference the New Year. -

Pardes JOURNAL of the ASSOCIATION for JEWISH STUDIES in GERMANY

PaRDeS JOURNAL OF THE ASSOCIATION FOR JEWISH STUDIES IN GERMANY JEWISH FAMILIES AND KINSHIP IN THE EARLY MODERN AND MODERN ERAS Ȳ 26 UNIVERSITÄTSVERLAG POTSDAM PaRDeS Zeitschrift der Vereinigung für Jüdische Studien e. V. / Journal of the Association for Jewish Studies in Germany Jewish Families and Kinship in the Early Modern and Modern Eras (2020) №. 26 Universitätsverlag Potsdam PaRDeS Zeitschrift der Vereinigung für Jüdische Studien e. V. / Journal of the Association for Jewish Studies in Germany Edited by Mirjam Thulin, Markus Krah, and Bianca Pick (Book Reviews) for the Association for Jewish Studies in Germany in association with the department of Jewish Studies and Religious Studies at University of Potsdam Jewish Families and Kinship in the Early Modern and Modern Eras (2020) №. 26 Universitätsverlag Potsdam ISSN (print) 1614-6492 ISSN (online) 1862-7684 ISBN 978-3-86956-493-7 Bibliographic information published by the Deutsche Nationalbibliothek: The Deutsche Nationalbibliothek lists this publication in the Deutsche Nationalbibliografie; de- tailed bibliographic data are available at http://dnb.dnb.de. The production of this issue of the journal was generously supported by the Leibniz Institute of European History (IEG) in Mainz, by Prof. Jonathan Schorsch, chair in Jewish Religious and Intellectual History at University of Potsdam’s School of Jewish Theology, and by the German Department of Johannes Gutenberg University Mainz. Universitätsverlag Potsdam 2020 Am Neuen Palais 10, 14469 Potsdam | http://verlag.ub.uni-potsdam.de/ phone.: +49 (0)331 977 2533 | fax: -2292 | [email protected] Editors: Markus Krah, Ph. D. ([email protected]) Dr. Mirjam Thulin ([email protected]) Bianca Pick, M. -

Download Catalogue

F i n e J u d a i C a . printed booKs, manusCripts, autograph Letters, graphiC & CeremoniaL art K e s t e n b au m & C om pa n y thursday, september 22nd, 2016 K est e n bau m & C o m pa ny . Auctioneers of Rare Books, Manuscripts and Fine Art A Lot 132 Catalogue of F i n e J u d a i C a . FEATURING: Fine Art Formerly in the Collections of Lady Charlotte Louise Adela Evelina Rothschild Behrens (1873-1947) & The Late Edmund Traub, Prague-London A Singular Collection of Early Printed Books & Rabbinic Manuscripts Sold by Order of the Execution Office, District High Court, Tel Aviv (Part IV) Property of Bibliophile and Book-Seller The Late Yosef Goldman, Brooklyn, NY Important Soviet, German and Early Zionist Posters Ceremonial Judaica & Folk Art From a Private Collection, Mid-Atlantic Seaboard ——— To be Offered for Sale by Auction, Thursday, 22nd September, 2016 at 3:00 pm precisely ——— Viewing Beforehand: Sunday, 18th September - 12:00 pm - 6:00 pm Monday, 19th September - 10:00 am - 6:00 pm Tuesday, 20th September - 10:00 am - 6:00 pm Wednesday, 21st September - 10:00 am - 6:00 pm No Viewing on the Day of Sale This Sale may be referred to as: “Yevsektsiya” Sale Number Seventy Illustrated Catalogues: $38 (US) * $45 (Overseas) KESTENBAUM & COMPANY Auctioneers of Rare Books, Manuscripts and Fine Art . 242 West 30th Street, 12th Floor, New York, NY 10001 • Tel: 212 366-1197 • Fax: 212 366-1368 E-mail: [email protected] • World Wide Web Site: www.Kestenbaum.net K est e n bau m & C o m pa ny . -

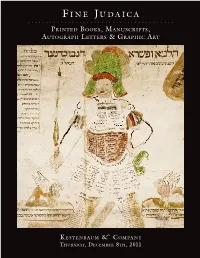

Fi N E Ju D a I

F i n e Ju d a i C a . pr i n t e d bo o K s , ma n u s C r i p t s , au t o g r a p h Le t t e r s & gr a p h i C ar t K e s t e n b a u m & Co m p a n y th u r s d a y , de C e m b e r 8t h , 2011 K e s t e n b a u m & Co m p a n y . Auctioneers of Rare Books, Manuscripts and Fine Art A Lot 334 Catalogue of F i n e Ju d a i C a . PRINTED BOOKS , MANUSCRI P TS , AUTOGRA P H LETTERS & GRA P HIC ART Featuring: Books from Jews’ College Library, London ——— To be Offered for Sale by Auction, Thursday, 8th December, 2011 at 3:00 pm precisely ——— Viewing Beforehand: Sunday, 4th December - 12:00 pm - 6:00 pm Monday, 5th December - 10:00 am - 6:00 pm Tuesday, 6th December - 10:00 am - 6:00 pm Wednesday 7th December - 10:00 am - 6:00 pm No Viewing on the Day of Sale. This Sale may be referred to as: “Omega” Sale Number Fifty-Three Illustrated Catalogues: $35 (US) * $42 (Overseas) KestenbauM & CoMpAny Auctioneers of Rare Books, Manuscripts and Fine Art . 242 West 30th street, 12th Floor, new york, NY 10001 • tel: 212 366-1197 • Fax: 212 366-1368 e-mail: [email protected] • World Wide Web site: www.Kestenbaum.net K e s t e n b a u m & Co m p a n y .