Program and Abstracts for 2008 Meeting

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

University of Cincinnati

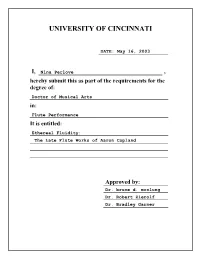

UNIVERSITY OF CINCINNATI DATE: May 16, 2003 I, Nina Perlove , hereby submit this as part of the requirements for the degree of: Doctor of Musical Arts in: Flute Performance It is entitled: Ethereal Fluidity: The Late Flute Works of Aaron Copland Approved by: Dr. bruce d. mcclung Dr. Robert Zierolf Dr. Bradley Garner ETHEREAL FLUIDITY: THE LATE FLUTE WORKS OF AARON COPLAND A thesis submitted to the Division of Research and Advanced Studies of the University of Cincinnati in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF MUSICAL ARTS (DMA) in the Division of Performance Studies of the College-Conservatory of Music 2003 by Nina Perlove B.M., University of Michigan, 1995 M.M., University of Cincinnati, 1999 Committee Chair: bruce d. mcclung, Ph.D. ABSTRACT Aaron Copland’s final compositions include two chamber works for flute, the Duo for Flute and Piano (1971) and Threnodies I and II (1971 and 1973), all written as memorial tributes. This study will examine the Duo and Threnodies as examples of the composer’s late style with special attention given to Copland’s tendency to adopt and reinterpret material from outside sources and his desire to be liberated from his own popular style of the 1940s. The Duo, written in memory of flutist William Kincaid, is a representative example of Copland’s 1940s popular style. The piece incorporates jazz, boogie-woogie, ragtime, hymnody, Hebraic chant, medieval music, Russian primitivism, war-like passages, pastoral depictions, folk elements, and Indian exoticisms. The piece also contains a direct borrowing from Copland’s film scores The North Star (1943) and Something Wild (1961). -

LINER NOTES Recorded Anthology of American Music, Inc

The Vision of Francis Goelet When and if the story of music patronage in the United States is ever written, Francis Goelet will emerge as the single most important individual supporter of composers as well as musical institutions and organizations that we’ve ever had. Unlike donors of buildings—museums, concert halls, and theaters—where names of donors are often prominently displayed, music philanthropy is apt to be noted when a piece is first performed and then is likely to fade into history. In the course of Francis Goelet’s lifetime he commissioned more symphonic and operatic works than any other American citizen. He paid for or contributed toward the staging of seventeen productions at the Metropolitan Opera, including three world premieres: Samuel Barber’s Vanessa and Antony and Cleopatra and John Corigliano’s The Ghosts of Versailles—but his most significant contribution was the commissioning of new music, starting in 1967 with a series of works to celebrate the New York Philharmonic’s 125th anniversary. Several of these have become twentieth-century landmarks. In 1977 he commissioned a series of concertos for the Philharmonic’s first-desk players, and to celebrate the Philharmonic’s 150th anniversary in 1992, he paid for another thirty-six works. Beginning with the American Composers Orchestra’s tenth anniversary he commissioned twenty-one symphonic scores, primarily from emerging composers. When New World Records was created in 1975 by the Rockefeller Foundation to celebrate American music at the time of our bicentennial celebrations, he was invited on the board and became its vice-chairman. At the conclusion of the Bicentennial he underwrote New World Records on his own, and this recording is a result of a continuation of his extraordinary legacy. -

20Th Century Book Inside

Y Y R R U U T T N N E E R R E E C C V V O O h h t t C C S S 0 0 I I music of the D D 2 2 DISCOVER MUSIC OF THE 2Oth CENTURY 8.558168–69 20th Century Cover 6/8/05 15:22 Page 1 20th Century Booklet revised 12/9/05 3:22 pm Page 3 DISCOVER music of the 20th CENTURY Contents page Track list 4 Music of the Twentieth Century, by David McCleery 9 I. Introduction 10 II. Pointing the Way Forward 13 III. Post-Romanticism 17 IV. Serialism and Twelve-Tone Music 24 V. Neoclassicism 34 VI. An English Musical Renaissance 44 VII. Nationalist Music 55 VIII. Music from Behind the Iron Curtain 64 IX. The American Tradition 74 X. The Avant Garde 85 XI. Beyond the Avant Garde 104 XII. A Second Musical Renaissance in England 118 XIII. Into the Present 124 Sources of featured panels 128 A Timeline of the Twentieth Century (music, history, art and architecture, literature) 130 Further Listening 150 Composers of the Twentieth Century 155 Map 164 Glossary 166 Credits 179 3 20th Century Booklet revised 12/9/05 3:22 pm Page 4 DISCOVER music of the 20th CENTURY Track List CD 1 Claude Debussy (1862–1918) 1 Prélude à l’après-midi d’un faune 10:33 BRT Philharmonic Orchestra, Brussels / Alexander Rahbari 8.550262 Arnold Schoenberg (1874–1951) Five Piano Pieces, Op. 23 2 Walzer 3:30 Peter Hill, piano 8.553870 Alban Berg (1885–1935) Violin Concerto 3 Movement 1: Andante – Scherzo 11:29 Rebecca Hirsch, violin / Netherlands Radio Symphony Orchestra / Eri Klas 8.554755 Anton Webern (1883–1945) Five Pieces, Op. -

Outline of Introduction to Contemporary Music, 2Nd Edition Joseph Machlis

Outline of Introduction to Contemporary Music, 2nd Edition Joseph Machlis Compliments of www.thereelscore.com Michael Morangelli – [email protected] Michael Morangelli Film Composer Worked with high quality samples. Delivery on DAT Has performed accompanied by the Audio Data files and either the extensively both in sequence or Finale Lead Sheet Conductors score if New York City and required. Boston. His credits include the Angelo All material is laid up to QuickTime for review with Tallaracco and Bob spotting and cue notes if required. January Big Bands, Fire & Ice Jazz Web Octet, and the Blue Rain Lounge Quartet. He was also staff guitarist for South Park Flash audio materials are optimized for file size and Recording Studio. laid up in Flash suitable for web display. Both the .fla file and the .swf file are accompanied by all sound and music samples in AIFF format (with In Boston 1985 - 2004, he has played with the Sound Designer II if required). George Pearson Group (local headliners at the Boston Jazz Society Jazz Festival in 1990), All Flash animations can be converted to QuickTime Urban Ambience, and was founder and leader of should that format be required. the Whats New Septet (1995). His Jazz compositions have been recorded by Comraderie Tapes and included in the missing links Tape Services Sampler. Original Music Composition Composing for film since 1996, he has provided Music Spotting scores for Board Stories, Rules of Order, the Music/Sound Design independent production American Lullaby, the Efx/Foley/VoiceOvers CityScape production Wastebasket, and Il for QuickTime/Flash Animation Moccio - an April 2004 New York Film and Video entry. -

Works Commissioned by Or Written for the New York Philharmonic (Including the New York Symphony Society)

Works Commissioned by or Written for the New York Philharmonic (Including the New York Symphony Society). Updated: August 31, 2011 Date Composer Work Conductor Soloists Premiere Funding Source Notes Nov. 14, 1925 Taylor, Symphonic Poem, “Jurgen” W. Damrosch World Commissioned by Damrosch for the Deems Premiere Symphony Society Dec 3, 1925 Gershwin Concerto for Piano in F W. Damrosch George Gershwin World Commissioned by Damrosch for the Premiere Symphony Society Dec 26, 1926 Sibelius Symphonic Poem Tapiola , W. Damrosch World Commisioned by The Symphony Op. 112 Premiere Society Feb 12, 1928 Holst Tone Poem Egdon Heath W. Damrosch World Commissioned by the Symphony Premiere Society Dec 20, 1936 James Overture, Bret Harte Barbirolli World American Composers Award Premiere Nov 4, 1937 Read Symphony No. 1 Barbirolli World American Composers Award Premiere Apr 2, 1938 Porter Symphony No. 1 Porter World American Composers Award Premiere Dec 18, 1938 Haubiel Passacaglia in A minor Haubiel World American Composers Award Premiere Jan 19, 1939 Van Vactor Symphony in D Van Vactor World American Composers Award Premiere Feb 26, 1939 Sanders Little Symphony in G Sanders World American Composers Award Premiere Jan 24, 1946 Stravinsky Symphony in Three Stravinsky World Movements Premiere Nov 16, 1948 Gould Philharmonic Waltzes Mitropoulos World Premiere Jan 14, 1960 Schuller Spectra Mitropoulos World In honor of Dimitri Mitropoulos Premiere Sep 23, 1962 Copland Connotations for Orchestra Bernstein World Celebrating the opening season of Premiere Philharmonic -

View List (.Pdf)

Symphony Society of New York Stadium Concert New York Philharmonic Commission New York Philharmonic 150th Anniversary Commission World Premieres New York Philharmonic Messages for the Millennium Commission as of November 30, 2020 NY PHIL Biennial NY PHIL Biennial Commission Joint Commission Members of / musicians from the New York Philharmonic Click to jump to decade 1842-99 | 1900-09 | 1910-19 | 1920-29 | 1930-39 | 1940-49 | 1950-59 1960-69 | 1970-79 | 1980-89 | 1990-99 | 2000-09 | 2010-19 | 2020 Composer Work Date Conductor 1842 – 1899 Loder Concert Overture, Marmion 17-Jan 1846 Loder Bristow Concert Overture, Op. 3 9-Jan 1847 Timm Bristow Symphony No. 4, Arcadian 14-Feb 1874 Bergmann Liszt Symphonic Poem No. 2, Tasso: lamento e trionfo 24-Mar 1877 L.Damrosch Tchaikovsky Piano Concerto No. 2 12-Nov 1881 Thomas R. Strauss Symphony in F minor, Op. 12 13-Dec 1884 Thomas Stanford Symphony No. 3 in F minor, Op. 28 (Irish) 28-Jan 1888 W.Damrosch Lalo Arlequin 28-Nov 1892 W.Damrosch Beach Scena and Aria from Mary Stuart 2-Dec 1892 W.Damrosch Dvořák Symphony No. 9, From the New World (formerly No. 5) 16-Dec 1893 Seidl Herbert Cello Concerto No. 2 9-Mar 1894 Seidl Damrosch Scarlet letter, The 04-Jan 1895 W.Damrosch 1900 – 1909 Hadley Symphony No. 2, The Four Seasons 21-Dec 1901 Paur Burmeister Dramatic Tone Poem, The Sisters 10-Jan 1902 Paur Rezniček Donna Dianna 23-Nov 1907 W.Damrosch Lyapunov Concerto for Piano and Orchestra 7-Dec 1907 W.Damrosch Hofmann Concerto for Pianoforte No. -

Aaron Copland: Works for Piano 1926-1948 New World NW 277

Aaron Copland: Works for Piano 1926-1948 New World NW 277 Virgil Thomson once said, “The way to write American music is simple. All you have to do is to be an American and then write any kind of music you wish.” Like most aphorisms, this one propounds a course of deceptive simplicity, for it replaces one question with another: “What kind of music do you wish to write?” In this context, “American music” is hardly an admissible reply. Around the turn of the century, most of America's professional composers of art music had completed their studies in Germany—and probably begun them with someone born in Germany or at least trained there (this was perfectly logical, a product of heavy German immigration into the United States and the strong musical traditions of the immigrants; there were simply more German musicians in this country than any other kind). These composers knew what kind of music they wanted to write, certainly. As Aaron Copland has described it: Their attitude was founded upon an admiration for the European art work and an identification with it that made the seeking out of any other art formula a kind of sacrilege. The challenge of the Continental art work was not: can we do better or can we also do something truly our own, but merely, can we do as well. But of course one never does “as well.” Meeting Brahms or Wagner on his own terms one is certain to come off second best. They loved the masterworks of Europe's mature culture not like creative personalities but like the schoolmasters that many of them became. -

Aaron Copland Success and Critical Acclaim

to the Pulitzer Prize-winning _Appalachian_ _Spring_ found both popular Aaron Copland success and critical acclaim. His decision to 'say it in the simplest possible terms' alienated some of his peers, who saw in it a repudiation of musical progress -- theirs and his own. But many who had been drawn to Copland's music through his use of familiar melodies were in turn perplexed by his use, beginning in the mid-1950's, of an individualized 12-tone compositional technique. His orchestral works _Connotations_ (1962) and _Inscape_ (1967) stand as perhaps the definitive statements of his mature, 'difficult' style. Copland never ceased to be an emissary and advocate of new music. In 1951, he became the first American composer to hold the position of Norton Aaron Copland photo © Roman Freulich Professor of Poetics at Harvard University; his lectures there were published as _Music and Imagination._ For 25 years he was a leading member of the An introduction to the music of Aaron Copland faculty at the Berkshire Music Center (Tanglewood). Throughout his career, he nurtured the careers of others, including Leonard Bernstein, Carlos Aaron Copland's name is, for many, synonymous with American music. It was Chavez, Toru Takemitsu, and David Del Tredici. He took up conducting while his pioneering achievement to break free from Europe and create a concert in his fifties, becoming a persuasive interpreter of his own music; he music that is recognizably, characteristically American. At the same time, he continued to conduct in concerts, on the radio, and on television until he was was able to stamp his music with a compositional personality so vivid as to 83. -

A Reading of Aaron Copland's Inscape

FROM OUTWARD APPEARANCE TO INNER REALITY: A READING OF AARON COPLAND’S INSCAPE Jeffrey S. Ensign, B.M. Thesis Prepared for the Degree of MASTER OF MUSIC UNIVERSITY OF NORTH TEXAS December 2010 APPROVED: Graham H. Phipps, Major Professor Stephen Slottow, Minor Professor Frank Heidlberger, Committee Member Eileen M. Hayes, Chair of the Division of Music History, Theory, and Ethnomusicology James C. Scott, Dean of the College of Music James D. Meernik, Acting Dean of the Robert B. Toulouse School of Graduate Studies Ensign, Jeffrey S. From Outward Appearance to Inner Reality: A Reading of Aaron Copland’s Inscape. Master of Music (Music Theory), December 2010, 72 pp., 47 illustrations, bibliography, 24 titles. Inspired by Gerard Manley Hopkins, the nineteenth-century English poet-priest, Copland composed the twelve-tone composition Inscape, realizing his own interpretation of Hopkins’s term “inscape” in a work that seems to move inward upon itself, where the outward appearance reflects the inner reality. The outward appearance is the boundary chords that frame the composition. The inner reality is the first complete statement of Copland’s original melodic idea at P-0, which occurs very close to the middle of Inscape. Copland establishes a dichotomy between the vertical sonority and the horizontal dyadic writing in the beginning section and generates motion inward through a disintegration, or liquidation, of these elements. After a journey through a series of tableaux, the music returns to the outer limit, or frame, reestablishing the dichotomy of the vertical and horizontal elements. Copyright 2010 by Jeffrey S. Ensign ii TABLE OF CONTENTS LIST OF EXAMPLES…………………………………………………………………………..v Chapter 1. -

![Aaron Copland Collection [Finding Aid]. Library of Congress. [PDF](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/1759/aaron-copland-collection-finding-aid-library-of-congress-pdf-7011759.webp)

Aaron Copland Collection [Finding Aid]. Library of Congress. [PDF

Aaron Copland Collection Processed by the Music Division of the Library of Congress Music Division, Library of Congress Washington, D.C. 2005 Contact information: http://hdl.loc.gov/loc.music/ perform.contact Finding Aid encoded by Library of Congress Music Division, 2005 Finding aid URL: http://hdl.loc.gov/loc.music/ eadmus.mu002006 Latest revision: 2011 January Collection Summary Title: Aaron Copland Collection Span Dates: 1841-1991 Bulk Dates: (bulk 1911-1990) Call No.: ML31.C7 Creator: Copland, Aaron, 1900- Extent: around 400,000 items; 564 boxes; 306 linear feet Language: Collection material in English Repository: Music Division, Library of Congress, Washington, D.C. Abstract: The Aaron Copland Collection consists of published and unpublished music by Copland and other composers, correspondence, writings, biographical material, datebooks, journals, professional papers including legal and financial material, photographs, awards, art work, and books. Of particular interest is the correspondence with Nadia Boulanger, which extent over 50 years, and with his long-time friend, Harold Clurman. Other significant correspondents are Leonard Bernstein, Paul Bowles, Benjamin Britten, Carlos Chávez, David Diamond, Roy Harris, Charles Ives, Claire Reis, Arnold Schoenberg, Roger Sessions, and Virgil Thomsom. The photographic collection of Copland's friend and confidant Victor Kraft, a professional photographer, forms part of the collection. Selected Search Terms The following terms have been used to index the description of this collection in the Library's online catalog. They are grouped by name of person or organization, by subject or location, and by occupation and listed alphabetically therein. People Bernstein, Leonard, 1918-1990--Correspondence. Boulanger, Nadia--Correspondence. Bowles, Paul, 1910-1999--Correspondence. -

Western Culture Has Roots in Ancient

37 13. What are some examples of Ravel's thought? La valse (Viennese waltzes), Bolero (Spain), Tzigane (Gypsy Chapter 35 style), violin sonata (blues), jazz (Concerto for the Left Between the World Wars: The Classical Tradition Hand) 1. [875] Music has long been linked to politics. 14. Who are members of Les Six? Why that designation? 2. (876) What was one thought on the relation of music and Arthur Honegger (1892-1955), Darius Milhaud (1892-1974), politics? What science supported it? Francis Poulenc (1899-1963), Germaine Tailleferre Music was independent; musicology focused on styles and (1892-1983), Georges Auric (1899-1983), Louis Durey procedures of the past rather than on its social function (1888-1979); parallel to the Mighty Five in Russia trying to escape foreign domination in music 3. What was the action in democracies where there was economic crisis between the world wars? What are 15. Who were their mentors? examples (genres) that they directed their attention? Erik Satie, Jean Cocteau Composers wanted to make their music have relevance; music for amateurs, theater, nationalism 16. How did they collaborate? Concerts, an albus of piano music, and Cocteau's absurdist 4. What role did the government play? play/ballet Les maries de la tour Eiffel (Newlyweds on Public schools had music in the curriculum (Zoltan Kodaly); the Eiffel Tower, 1921) radio was controlled by the government in Europe; the New Deal in the U.S. employed musicians/composers; 17. Which one left very early? totalitarian governments wanted music that supported the Durey state and its ideologies; the Soviet Union and Nazi Germany sought to suppress modernism 18. -

Contents More Information

Cambridge University Press 978-0-521-89955-0 - Twelve-Tone Music in America Joseph N. Straus Table of Contents More information Contents List of music examples page xi Preface xvii Part One: Thirty-seven ways to write a twelve-tone piece 1 1 “Ultramodern” composers: Adolph Weiss, Wallingford Riegger, Carl Ruggles, and Ruth Crawford Seeger 3 Adolph Weiss and “twelve-tone rows in four forms”: Prelude for Piano, No. 11 (1927) 3 Wallingford Riegger and the serial/chromatic dichotomy: Dichotomy (1931–1932) 7 Carl Ruggles and “dissonant counterpoint”: Evocations II (1941) 11 Ruth Crawford Seeger and rotational/transpositional schemes: Diaphonic Suite No. 1 (1930) 16 2 European immigrants: Arnold Schoenberg, Ernst Krenek, Igor Stravinsky, and Stefan Wolpe 21 Arnold Schoenberg and hexachordal inversional combinatoriality: Piano Concerto, Op. 42 (1942) 21 Ernst Krenek and modal rotation: Lamentatio Jeremiae Prophetae, Op. 43 (1942) 28 Igor Stravinsky and rotational arrays: “Exaudi,” from Requiem Canticles (1966) 34 Stefan Wolpe and the “structures of fantasy”: Form for Piano (1959) 40 3 Postwar pioneers: Milton Babbitt, Elliott Carter, George Perle, Aaron Copland, and Roger Sessions 46 Milton Babbitt and trichordal arrays: Danci for solo guitar (1996) 47 Elliott Carter and twelve-note chords: Caténaires (2006) 52 George Perle and twelve-tone tonality: Six New Etudes, “Romance” (1984) 56 Aaron Copland and “freely interpreted tonalism”: Inscape (1967) 60 © in this web service Cambridge University Press www.cambridge.org Cambridge University Press 978-0-521-89955-0 - Twelve-Tone Music in America Joseph N. Straus Table of Contents More information viii Contents Roger Sessions and “an organic pattern of sounds and intervals”: When Lilacs Last in the Dooryard Bloom’d (1970) 66 4 An older generation (composers born before 1920): Ben Weber, George Rochberg, Ross Lee Finney, Barbara Pentland, and Roque Cordero 71 Ben Weber and an “available form”: Bagatelle No.