Contents More Information

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

New and Old Tendencies in Labour Mediation Among Early Twentieth-Century US and European Composers

Anna G. Piotrowska New and Old Tendencies in Labour Mediation among Early Twentieth-Century U.S. and European Composers: An Outline of Applied Attitudes1 Abstract: New and Old Tendencies in Labour Mediation among Early Twen- tieth-Century U.S. and European Composers: An Outline of Applied Atti- tudes.This paper presents strategies used by early twentieth-century compos- ers in order to secure an income. In the wake of new economic realities, the Romantic legacy of the musician as creator was confronted by new expecta- tions of his position within society. An analysis of written accounts by com- posers of various origins (British, German, French, Russian or American), including their artistic preferences and family backgrounds, reveals how they often resorted to jobs associated with musicianship such as conducting or teaching. In other cases, they willingly relied on patronage or actively sought new sources of employment offered by the nascent film industry and assorted foundations. Finally, composers also benefited from organized associations and leagues that campaigned for their professional recognition. Key Words: composers, 20th century, employment, vacation, film industry, patronage, foundations Introduction Strategies undertaken by early twentieth-century composers to secure their income were highly determined by their position within society.2 Already around 1900, composers confronted a new reality: the definition of a composer inherited from earlier centuries no longer applied. As will be demonstrated by an analysis of their Anna G. Piotrowska, Institute of Musicology, the Jagiellonian University (Krakow), ul. Westerplatte 10, PL-31-033 Kraków; [email protected] ÖZG 24 | 2013 | 1 131 memoirs, diaries and correspondence, those educated as professional musicians and determined to make their living as active composers had to deal with similar career challenges – regardless of their origins (British, German, French, Russian or Ameri- can), their artistic preferences, or their family backgrounds. -

Msm Camerata Nova

Saturday, March 6, 2021 | 12:15 PM Livestreamed from Neidorff-Karpati Hall MSM CAMERATA NOVA George Manahan (BM ’73, MM ’76), Conductor PROGRAM JAMES LEE III A Narrow Pathway Traveled from Night Visions of Kippur (b. 1975) CHARLES WUORINEN New York Notes (1938–2020) (Fast) (Slow) HEITOR VILLA-LOBOS Chôros No. 7 (1887–1959) MAURICE RAVEL Introduction et Allegro (1875–1937) CAMERATA NOVA VIOLIN 1 VIOLA OBOE SAXOPHONE HARP Youjin Choi Sara Dudley Aaron Zhongyang Ling Minyoung Kwon New York, New York New York, New York Haettenschwiller Beijing, China Seoul, South Korea Baltimore, Maryland VIOLIN 2 CELLO PERCUSSION PIANO Ally Cho Rei Otake CLARINET Arthur Seth Schultheis Melbourne, Australia Tokyo, Japan Ki-Deok Park Dhuique-Mayer Baltimore, Maryland Chicago, Illinois Champigny-Sur-Marne, France FLUTE Tarun Bellur Marcos Ruiz BASSOON Plano, Texas Miami, Florida Matthew Pauls Simi Valley, California ABOUT THE ARTISTS George Manahan, Conductor George Manahan is in his 11th season as Director of Orchestral Activities at Manhattan School of Music, as well as Music Director of the American Composers Orchestra and the Portland Opera. He served as Music Director of the New York City Opera for 14 seasons and was hailed for his leadership of the orchestra. He was also Music Director of the Richmond Symphony (VA) for 12 seasons. Recipient of Columbia University’s Ditson Conductor’s Award, Mr. Manahan was also honored by the American Society of Composers and Publishers (ASCAP) for his “career-long advocacy for American composers and the music of our time.” His Carnegie Hall performance of Samuel Barber’s Antony and Cleopatra was hailed by audiences and critics alike. -

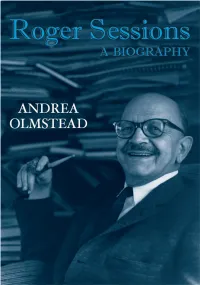

Roger Sessions: a Biography

ROGER SESSIONS: A BIOGRAPHY Recognized as the primary American symphonist of the twentieth century, Roger Sessions (1896–1985) is one of the leading representatives of high modernism. His stature among American composers rivals Charles Ives, Aaron Copland, and Elliott Carter. Influenced by both Stravinsky and Schoenberg, Sessions developed a unique style marked by rich orchestration, long melodic phrases, and dense polyphony. In addition, Sessions was among the most influential teachers of composition in the United States, teaching at Princeton, the University of California at Berkeley, and The Juilliard School. His students included John Harbison, David Diamond, Milton Babbitt, Frederic Rzewski, David Del Tredici, Conlon Nancarrow, Peter Maxwell Davies, George Tson- takis, Ellen Taaffe Zwilich, and many others. Roger Sessions: A Biography brings together considerable previously unpublished arch- ival material, such as letters, lectures, interviews, and articles, to shed light on the life and music of this major American composer. Andrea Olmstead, a teaching colleague of Sessions at Juilliard and the leading scholar on his music, has written a complete bio- graphy charting five touchstone areas through Sessions’s eighty-eight years: music, religion, politics, money, and sexuality. Andrea Olmstead, the author of Juilliard: A History, has published three books on Roger Sessions: Roger Sessions and His Music, Conversations with Roger Sessions, and The Correspondence of Roger Sessions. The author of numerous articles, reviews, program and liner notes, she is also a CD producer. This page intentionally left blank ROGER SESSIONS: A BIOGRAPHY Andrea Olmstead First published 2008 by Routledge 711 Third Avenue, New York, NY, 10017, USA Simultaneously published in the UK by Routledge 2 Park Square, Milton Park, Abingdon, Oxon OX14 4RN Routledge is an imprint of the Taylor & Francis Group, an informa business © 2008 Andrea Olmstead Typeset in Garamond 3 by RefineCatch Limited, Bungay, Suffolk All rights reserved. -

Concert Programdownload Pdf(349

The University at Buffalo Department of Music and The Robert & Carol Morris Center for 21st Century Music present Stockhausen's Mantra For Two Pianos Eric Huebner and Steven Beck, pianos Sound and electronic interface design: Ryan MacEvoy McCullough Sound projection: Chris Jacobs and Ryan MacEvoy McCullough Saturday, October 14, 2017 7:30pm Lippes Concert Hall in Slee Hall PROGRAM Mantra (1970) Karlheinz Stockhausen (1928 – 2007) Program Note by Katherine Chi To say it as simply as possible, Mantra, as it stands, is a miniature of the way a galaxy is composed. When I was composing the work, I had no accessory feelings or thoughts; I knew only that I had to fulfill the mantra. And it demanded itself, it just started blossoming. As it was being constructed through me, I somehow felt that it must be a very true picture of the way the cosmos is constructed, I’ve never worked on a piece before in which I was so sure that every note I was putting down was right. And this was due to the integral systemization - the combination of the scalar idea with the idea of deriving everything from the One. It shines very strongly. - Karlheinz Stockhausen Mantra is a seminal piece of the twentieth century, a pivotal work both in the context of Stockhausen’s compositional development and a tour de force contribution to the canon of music for two pianos. It was written in 1970 in two stages: the formal skeleton was conceived in Osaka, Japan (May 1 – June 20, 1970) and the remaining work was completed in Kürten, Germany (July 10 – August 18, 1970). -

A Heretic in the Schoenberg Circle: Roberto Gerhard's First Engagement with Twelve-Tone Procedures in Andantino

Twentieth-Century Music 16/3, 557–588 © Cambridge University Press 2019. This is an Open Access article, distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution licence (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted re-use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited. doi: 10.1017/S1478572219000306 A Heretic in the Schoenberg Circle: Roberto Gerhard’s First Engagement with Twelve-Tone Procedures in Andantino DIEGO ALONSO TOMÁS Abstract Shortly before finishing his studies with Arnold Schoenberg, Roberto Gerhard composed Andantino,a short piece in which he used for the first time a compositional technique for the systematic circu- lation of all pitch classes in both the melodic and the harmonic dimensions of the music. He mod- elled this technique on the tri-tetrachordal procedure in Schoenberg’s Prelude from the Suite for Piano, Op. 25 but, unlike his teacher, Gerhard treated the tetrachords as internally unordered pitch-class collections. This decision was possibly encouraged by his exposure from the mid- 1920s onwards to Josef Matthias Hauer’s writings on ‘trope theory’. Although rarely discussed by scholars, Andantino occupies a special place in Gerhard’s creative output for being his first attempt at ‘twelve-tone composition’ and foreshadowing the permutation techniques that would become a distinctive feature of his later serial compositions. This article analyses Andantino within the context of the early history of twelve-tone music and theory. How well I do remember our Berlin days, what a couple we made, you and I; you (at that time) the anti-Schoenberguian [sic], or the very reluctant Schoenberguian, and I, the non-conformist, or the Schoenberguian malgré moi. -

A Conductor's Study of George Rochberg's Three Psalm Settings David Lawrence Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College

Louisiana State University LSU Digital Commons LSU Major Papers Graduate School 2002 A conductor's study of George Rochberg's three psalm settings David Lawrence Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_majorpapers Part of the Music Commons Recommended Citation Lawrence, David, "A conductor's study of George Rochberg's three psalm settings" (2002). LSU Major Papers. 51. https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_majorpapers/51 This Major Paper is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at LSU Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in LSU Major Papers by an authorized graduate school editor of LSU Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. A CONDUCTOR’S STUDY OF GEORGE ROCHBERG’S THREE PSALM SETTINGS A Monograph Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of the Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College in partial fulfillment of the Requirements for the degree of Doctor of Musical Arts in School of Music By David Alan Lawrence B.M.E., Abilene Christian University, 1987 M.M., University of Washington, 1994 August 2002 ©Copyright 2002 David Alan Lawrence All rights reserved. ii TABLE OF CONTENTS LIST OF TABLES ....................................................................................................................v LIST OF FIGURES..................................................................................................................vi LIST -

Ojai North Music Festival

CAL PERFORMANCES PRESENTS Thursday–Saturday, June 19–21, 2014 Hertz Hall Ojai North Music Festival Jeremy Denk Music Director, 2014 Ojai Music Festival Thomas W. Morris Artistic Director, Ojai Music Festival Matías Tarnopolsky Executive and Artistic Director, Cal Performances Robert Spano, conductor Storm Large, vocalist Timo Andres, piano Aubrey Allicock, bass-baritone Kim Josephson, baritone Dominic Armstrong, tenor Ashraf Sewailam, bass-baritone Rachel Calloway, mezzo-soprano Peabody Southwell, mezzo-soprano Keith Jameson, tenor Jennifer Zetlan, soprano The Knights Eric Jacobsen, conductor Brooklyn Rider Uri Caine Ensemble Hudson Shad Ojai Festival Singers Kevin Fox, conductor Ojai North is a co-production of the Ojai Music Festival and Cal Performances. Ojai North is made possible, in part, by Patron Sponsors Liz and Greg Lutz. Cal Performances’ – season is sponsored by Wells Fargo. CAL PERFORMANCES 13 FESTIVAL SCHEDULE Thursday–Saturday, June 19–21, 2014 Hertz Hall Ojai North Music Festival FESTIVAL SCHEDULE Thursday, June <D, =;<?, Cpm Welcome : Cal Performances Executive and Artistic Director Matías Tarnopolsky Concert: Bay Area première of The Classical Style: An Opera (of Sorts) plus Brooklyn Rider plays Haydn Brooklyn Rider Johnny Gandelsman, violin Colin Jacobsen, violin Nicholas Cords, viola Eric Jacobsen, cello The Knights Aubrey Allicock, bass-baritone Dominic Armstrong, tenor Rachel Calloway, mezzo-soprano Keith Jameson, tenor Kim Josephson, baritone Ashraf Sewailam, bass-baritone Peabody Southwell, mezzo-soprano Jennifer Zetlan, soprano Mary Birnbaum, director Robert Spano, conductor Friday, June =;, =;<?, A:>;pm Talk: The creative team of The Classical Style: An Opera (of Sorts) —Jeremy Denk, Steven Stucky, and Mary Birnbaum—in a conversation moderated by Matías Tarnopolsky PLAYBILL FESTIVAL SCHEDULE Cpm Concert: Second Bay Area performance of The Classical Style: An Opera (of Sorts) plus Brooklyn Rider plays Haydn Same performers as on Thursday evening. -

Contact: a Journal for Contemporary Music (1971-1988) Citation

Contact: A Journal for Contemporary Music (1971-1988) http://contactjournal.gold.ac.uk Citation Toplis, Gloria. 1983. ‘Stravinsky’s Pitch Organisation Re-Examined’. Contact, 27. pp. 35-38. ISSN 0308-5066. ! 36 material, each involving different textures, registers, Example 1 harmonies, rhythms, and metres, are set synchro- nically side by side; when considered apart from their immediate context, the blocks may be seen to possess one or another of these parameters in common.' The same author has defined the structur- ing of the first movement of the Symphony in C ( 1938- 40)-one of the neoclassical works most obviously conform to the dictates of functional tonality. The akin in spirit to Classical models-not in terms of the appropriateness of the octatonic theory to Stravin- tonal relationships of sonata form, but in terms of the sky' s output becomes increasingly obvious the more temporal proportion to one another of the sections closely the constitution of the scale itself is examined. (established by means of rather ill-defined tonal For example, each degree articulating a division at areas), which is very much the same as that of a the minor third supports both a minor and a major typical sonata form movement. 3 triad-in Example 1 C supports the triads C-E flat-G Stravinsky students in the sixties were strongly and C-E-G, E flat supports the triads E flat-G flat-B influenced by the somewhat scathing and (in the flat and E flat-G-B flat, and so on; overlapping opinion of later analysts) harmful remarks of Pierre tetrachords a minor third apart contain interlocking Boulez on the composer's compositional technique in minor/major thirds-C-C sharp-D sharp-E, D sharp- works following The Rite of Spring (1911-13). -

High Fidelity's Description ) a D Q F L V F R (Modem Music, 1944

) ( ' / "New York-born composer whom a good many of York Times and leading magazines. his American colleagues regard as the best musical Arthur Berger was born in New York City on May stylist among them," is High Fidelity's description 15, 1912. When his family acquired a piano in 1921, of Arthur Berger (Feb., 1957). His stylism is marked his older sister received piano lessons which he by a highly personal stamp and capacity for precise learned before she did, and he played by ear. Between shape. Time Magazine (April 27, 1953) stated "it eleven and sixteen, aside from piano lessons, he was clear that Berger had a style of his own." was musically self-taught, and by 1928 when he "Clarity, refinement, perfect timing and impecca- entered New York City College he was writing tra- bly clean workmanship are the keynotes to his style," ditional sonatas. Since the College offered little in wrote Alfred Frankenstein (San F~ancisco Chronicle, music he later transferred to New York University, June 6, 1948). He "is the sort of musician who thinks working mainly in the education division with Vincent twice before he reaches for the staff-paper." In the Jones. There, along with two fellow students, he same vein Darius Milhaud remarked on his "loving extolled Charles lves as early as 1930, entered the attention to minute detail" (Modem Music, 1944). vital set that Henry Cowell attracted, and also became The Time article already quoted points out that part of the Young Composers Group that formed after a work '.'is technically finished, Berger often around Aaron Copland as guardian. -

Boston Symphony Orchestra Concert Programs, Summer, 1963-1964

TANGLEWOOD Festival of Contemporary American Music August 9, 10, 11, 12, 13, 1964 Sponsored by the Berkshire Music Center In Cooperation with the Fromm Music Foundation RCA Victor R£D SEAL festival of Contemporary American Composers DELLO JOIO: Fantasy and Variations/Ravel: Concerto in G Hollander/Boston Symphony Orchestra/Leinsdorf LM/LSC-2667 COPLAND: El Salon Mexico Grofe-. Grand Canyon Suite Boston Pops/ Fiedler LM-1928 COPLAND: Appalachian Spring The Tender Land Boston Symphony Orchestra/ Copland LM/LSC-240i HOVHANESS: BARBER: Mysterious Mountain Vanessa (Complete Opera) Stravinsky: Le Baiser de la Fee (Divertimento) Steber, Gedda, Elias, Mitropoulos, Chicago Symphony/Reiner Met. Opera Orch. and Chorus LM/LSC-2251 LM/LSC-6i38 FOSS: IMPROVISATION CHAMBER ENSEMBLE Studies in Improvisation Includes: Fantasy & Fugue Music for Clarinet, Percussion and Piano Variations on a Theme in Unison Quintet Encore I, II, III LM/LSC-2558 RCA Victor § © The most trusted name in sound BERKSHIRE MUSIC CENTER ERICH Leinsdorf, Director Aaron Copland, Chairman of the Faculty Richard Burgin, Associate Chairman of the Faculty Harry J. Kraut, Administrator FESTIVAL of CONTEMPORARY AMERICAN MUSIC presented in cooperation with THE FROMM MUSIC FOUNDATION Paul Fromm, President Alexander Schneider, Associate Director DEPARTMENT OF COMPOSITION Aaron Copland, Head Gunther Schuller, Acting Head Arthur Berger and Lukas Foss, Guest Teachers Paul Jacobs, Fromm Instructor in Contemporary Music Stanley Silverman and David Walker, Administrative Assistants The Berkshire Music Center is the center for advanced study in music sponsored by the BOSTON SYMPHONY ORCHESTRA Erich Leinsdorf, Music Director Thomas D. Perry, Jr., Manager BALDWIN PIANO RCA VICTOR RECORDS — 1 PERSPECTIVES OF NEW MUSIC Participants in this year's Festival are invited to subscribe to the American journal devoted to im- portant issues of contemporary music. -

Miriam Gideon's Cantata, the Habitable Earth

Louisiana State University LSU Digital Commons LSU Major Papers Graduate School 2003 Miriam Gideon's cantata, The aH bitable Earth: a conductor's analysis Stella Panayotova Bonilla Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_majorpapers Part of the Music Commons Recommended Citation Bonilla, Stella Panayotova, "Miriam Gideon's cantata, The aH bitable Earth: a conductor's analysis" (2003). LSU Major Papers. 20. https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_majorpapers/20 This Major Paper is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at LSU Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in LSU Major Papers by an authorized graduate school editor of LSU Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. MIRIAM GIDEON’S CANTATA, THE HABITABLE EARTH: A CONDUCTOR’S ANALYSIS A Monograph Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of the Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Musical Arts in The School of Music by Stella Panayotova Bonilla B.M., State Academy of Music, Sofia, Bulgaria, 1991 M.M., Louisiana State University, 1994 August 2003 ©Copyright 2003 Stella Panayotova Bonilla All rights reserved ii DEDICATION To you mom, and to the memory of my beloved father. iii ACKNOWLEDGMENTS Thanks to Dr. Kenneth Fulton for his guidance through the years, his faith in me and his invaluable help in accomplishing this project. Thanks to Dr. Robert Peck for his inspirational insight. Thanks to Dr. Cornelia Yarbrough and Dr. -

Guide to the Milt Gabler Papers

Guide to the Milt Gabler Papers NMAH.AC.0849 Paula Larich and Matthew Friedman 2004 Archives Center, National Museum of American History P.O. Box 37012 Suite 1100, MRC 601 Washington, D.C. 20013-7012 [email protected] http://americanhistory.si.edu/archives Table of Contents Collection Overview ........................................................................................................ 1 Administrative Information .............................................................................................. 2 Arrangement..................................................................................................................... 3 Scope and Contents........................................................................................................ 3 Biographical / Historical.................................................................................................... 2 Names and Subjects ...................................................................................................... 4 Container Listing ............................................................................................................. 5 Series 1: Personal Correspondence, 1945-1993..................................................... 5 Series 2: Writings, 1938 - 1991............................................................................... 7 Series 3: Music Manuscripts and Sheet Music,, 1927-1981.................................. 10 Series 4: Personal Financial and Legal Records, 1947-2000...............................