The Hospital Patient Service in Transition: a Study of the Development of Totality of Care

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Our Ref : TP/VAL/Q575/A

For Discussion WCDC Paper On 09.01.2018 No.: 2/2018 Proposed Amendments to the Road Improvement Works at Kennedy Road, and the Junction of Queen’s Road East and Kennedy Road, Wan Chai PURPOSE 1. This paper aims to seek Members’ views on the proposed amendments to the Road Improvement Works (“RIW”) following the presentation by the representatives of Hopewell Holdings Limited to Wan Chai District Council on 10 January 2017 regarding the latest development scheme of Hopewell Centre II and the associated RIW amendments. BACKGROUND 2. The original RIW was gazetted in April 2009 and authorized by the Chief Executive in Council in July 2010. The RIW comprises three parts; namely road widening at Kennedy Road, road widening at the junction of Queen’s Road East and Kennedy Road, and road widening at the junction of Spring Garden Lane and Queen’s Road East Note 1. Please refer to the Key Plan in 2009 Gazette at Appendix 1. 3. In order to preserve more trees, during the detailed design of the road work, Hopewell Holdings Limited proposed to amend the RIW at Kennedy Road and at the junction of Queen’s Road East and Kennedy Road. The proposed amendments to the RIW have been submitted to the relevant Government departments for comment and are considered acceptable in principle. On 11 August 2017, the planning application (No. A/H5/408) of the latest development scheme of Hopewell Centre II was approved with conditions by the Metro Planning Committee of the Town Planning Board including an approval condition on the design and implementation of the related RIW. -

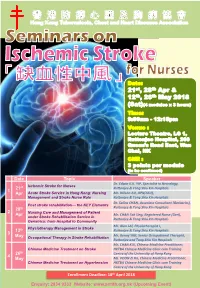

21St, 28Th Apr & 12Th, 26Th May 2018 (Sat)(4 Modules X 3 Hours)

Date: 21st, 28th Apr & 12th, 26th May 2018 (Sat)(4 modules x 3 hours) Time: 9:00am - 12:15pm Venue : Lecture Theatre, LG 1, Ruttonjee Hospital, 266 Queen’s Road East, Wan Chai, HK CNE : 3 points per module (to be confirmed) Date Topic Speaker Dr. Edwin K.K. YIP, Specialist in Neurology, Ischemic Stroke for Nurses 21st Ruttonjee & Tang Shiu Kin Hospitals 1 Apr Acute Stroke Service in Hong Kong: Nursing Mr. Wilson AU, APN(ASU), Management and Stroke Nurse Role Ruttonjee & Tang Shiu Kin Hospitals Dr. Selina CHAN, Associate Consultant (Geriatrics), Post stroke rehabilitation— the KEY Elements 28th Ruttonjee & Tang Shiu Kin Hospitals 2 Nursing Care and Management of Patient Apr Mr. CHAN Tak Sing, Registered Nurse (Geri), under Stroke Rehabilitation Service in Ruttonjee & Tang Shiu Kin Hospitals Geriatrics: from Hospital to Community Mr. Alan LAI, Physiotherapist I, Physiotherapy Management in Stroke 12th Ruttonjee & Tang Shiu Kin Hospitals 3 Mr. Benny YIM, Senior Occupational Therapist, May Occupational Therapy in Stroke Rehabilitation Ruttonjee and Tang Shiu Kin Hospitals Mr. CHAN KUI, Chinese Medicine Practitioner, Chinese Medicine Treatment on Stroke HKTBA Chinese Medicine Clinic cum Training 26th Centre of the University of Hong Kong 4 May Ms. POON Zi Ha, Chinese Medicine Practitioner, Chinese Medicine Treatment on Hypertension HKTBA Chinese Medicine Clinic cum Training Centre of the University of Hong Kong Enrollment Deadline: 18th April 2018 Enquiry: 2834 9333 Website: www.antitb.org.hk (Upcoming Event) Seminars on “Ischemic Stroke” for Nurses Objectives a) To strengthen, update and develop knowledge of nurses on the topic of endocrine system. b) To enhance the skills and technique in daily practice. -

1193Rd Minutes

Minutes of 1193rd Meeting of the Town Planning Board held on 17.1.2019 Present Permanent Secretary for Development Chairperson (Planning and Lands) Ms Bernadette H.H. Linn Professor S.C. Wong Vice-chairperson Mr Lincoln L.H. Huang Mr Sunny L.K. Ho Dr F.C. Chan Mr David Y.T. Lui Dr Frankie W.C. Yeung Mr Peter K.T. Yuen Mr Philip S.L. Kan Dr Lawrence W.C. Poon Mr Wilson Y.W. Fung Dr C.H. Hau Mr Alex T.H. Lai Professor T.S. Liu Ms Sandy H.Y. Wong Mr Franklin Yu - 2 - Mr Daniel K.S. Lau Ms Lilian S.K. Law Mr K.W. Leung Professor John C.Y. Ng Chief Traffic Engineer (Hong Kong) Transport Department Mr Eddie S.K. Leung Chief Engineer (Works) Home Affairs Department Mr Martin W.C. Kwan Deputy Director of Environmental Protection (1) Environmental Protection Department Mr. Elvis W.K. Au Assistant Director (Regional 1) Lands Department Mr. Simon S.W. Wang Director of Planning Mr Raymond K.W. Lee Deputy Director of Planning/District Secretary Ms Jacinta K.C. Woo Absent with Apologies Mr H.W. Cheung Mr Ivan C.S. Fu Mr Stephen H.B. Yau Mr K.K. Cheung Mr Thomas O.S. Ho Dr Lawrence K.C. Li Mr Stephen L.H. Liu Miss Winnie W.M. Ng Mr Stanley T.S. Choi - 3 - Mr L.T. Kwok Dr Jeanne C.Y. Ng Professor Jonathan W.C. Wong Mr Ricky W.Y. Yu In Attendance Assistant Director of Planning/Board Ms Fiona S.Y. -

Accounts of the Government for the Year Ended 31 March 2008 (Cash-Based)

Capital Works Reserve Fund STATEMENT OF PROJECT PAYMENTS FOR 2007-08 Head 708 — CAPITAL SUBVENTIONS AND MAJOR SYSTEMS AND EQUIPMENT Subhead Approved Original Project Estimate Estimate Cumulative Expenditure Amended to 31.3.2008 Estimate Actual $’000 $’000 $’000 CAPITAL SUBVENTIONS Education Subventions Primary 8008EA Primary school at Jockey Club Road, Sheung Shui 90,700 38,522 24,077 38,522 19,301 8013EA Redevelopment of Heep Yunn Primary School at 63,350 3,038 No. 1 Farm Road, Kowloon 53,228 3,038 - 8015EA Extension to St. Mary’s Canossian School at 162 71,300 10,648 Austin Road, Kowloon 52,685 10,648 - 8016EA Redevelopment of the former premises of The 83,200 3,108 Church of Christ in China Chuen Yuen Second 59,645 3,108 93 Primary School at Sheung Kok Street, Kwai Chung 8017EA Redevelopment of La Salle Primary School at 1D 160,680 5,955 La Salle Road, Kowloon 152,559 5,955 - 8018EA A 30-classroom primary school in Diocesan Boys’ 129,100 11,315 School campus at 131 Argyle Street, Kowloon 119,965 11,315 3,527 8019EA Redevelopment of Yuen Long Chamber of 88,100 40,000 Commerce Primary School at Castle Peak Road, 51,279 40,000 32,068 Yuen Long 8023EA Reprovisioning of The Church of Christ in China 89,700 9,512 Kei Tsz Primary School at Tsz Wan Shan Road, 73,775 9,512 1,892 Wong Tai Sin 8025EA Redevelopment of St. Stephen’s Girls’ Primary 100,000 40,658 School at Park Road, Mid-levels 26,565 40,658 26,565 8026EA A direct subsidy scheme primary school at Nam 105,600 78,817 Fung Path, Wong Chuk Hang 94 78,817 12 8027EA Extension and conversion to St. -

Birth Record

eHR Sharable Data - Birth Record May 2018 © HKSAR Government eHR Sharable Data - Birth Record Form Category 1 Entity Name Entity ID Definition Data Type Data Type Validation Rule Repeated Code Table Remark Data requirement Data requirement Data requirement Example (Certified Example (Certified Example (Certified (code) (description) Data (Certified Level 1) (Certified Level 2) (Certified Level 3) Level 1) Level 2) Level 3) Birth Birth datetime 100310 The birth date or birth datetime of a patient TS Time stamp M M M 11/02/2012 20/12/2011 21:22 09/12/2001 23:59 Record Birth Birth Birth institution code 1003346 [eHR value] of the "Birth institution" code table, to define CE Coded Birth institution NA NA M PMH Record Institution the healthcare institution who reported the birth data to element the Immigration Department Birth Birth Birth institution description 1003107 [eHR description] of the "Birth institution" code table, it ST String Birth institution NA NA M Princess Margaret Record Institution should be the corresponding description of the selected Hospital [Birth institution code]. Birth institution description is to define the healthcare institution who reported the birth data to the Immigration Department. Birth Birth Birth institution local description 1003108 The local description of the healthcare institution who ST String M M M St. Paul Hospital St. Paul Hospital Princess Margaret Record Institution reported the birth data to the Immigration Department. Hospital Birth Birth Birth location code 1003102 [eHR value] of the "Birth location" code table, to define CE Coded Birth location NA NA O BBA Record Location the location where the patient was born element Birth Birth Birth location description 1003103 [eHR description] of the "Birth location" code table, it ST String Birth location NA NA M if [Birth location code] Born before arrival Record Location should be the corresponding description of the selected is given [Birth location code]. -

Prospective Assessment of the Hong Kong Hospital Authority Universal

Prospective assessment of the Hong Kong Hospital ORIGINAL ARTICLE Authority universal Down syndrome screening programme Daljit S Sahota 邵浩達 WC Leung 梁永昌 Objective To evaluate the performance of the locally developed universal WP Chan 陳運鵬 Down syndrome screening programme. William WK To 杜榮基 Elizabeth T Lau 劉嚴德光 Design Population-based cohort study in the period July 2010 to June 2011 inclusive. TY Leung 梁德楊 Setting Four Hong Kong Hospital Authority Departments of Obstetrics and Gynaecology and a central university-based laboratory for maternal serum processing and risk determination. Participants Women were offered either a first-trimester combined test (nuchal translucency, free beta human chorionic gonadotropin, and pregnancy-associated plasma protein-A) or nuchal- translucency-only test, or a second-trimester double test (alpha-fetoprotein and total human chorionic gonadotropin) for detection of Down syndrome according to their gestational age. Those with a trisomy 21 term risk of 1:250 or higher were offered a diagnostic test. Results A total of 16 205 pregnancies were screened of which 13 331 (82.3%) had a first-trimester combined test, 125 (0.8%) had a nuchal-translucency test only, and 2749 (17.0%) had a second- trimester double test. There were 38 pregnancies affected by Down syndrome. The first-trimester screening tests had a 91.2% (31/34) detection rate with a screen-positive rate of 5.1% (690/13 Key words 456). The second-trimester test had a 100% (4/4) detection rate Down syndrome; First trimester with a screen-positive rate of 6.3% (172/2749). There were screening; Second trimester screening; seven (0.9%) pregnancies that miscarried following an invasive Nuchal translucency; Quality control diagnostic test. -

Hospital Authority Special Visiting Arrangement in Hospitals/Units with Non-Acute Settings Under Emergency Response Level Notes to Visitors

Hospital Authority Special Visiting Arrangement in Hospitals/Units with Non-acute Settings under Emergency Response Level Notes to Visitors 1. Hospital Authority implemented special visiting arrangement in four phases on 21 April 2021, 29 May 2021, 25 June 2021 and 23 July 2021 respectively (as appended table). Cluster Hospitals/Units with non-acute settings Cheshire Home, Chung Hom Kok Ruttonjee Hospital Hong Kong East Mixed Infirmary and Convalescent Wards Cluster Tung Wah Eastern Hospital Wong Chuk Hang Hospital Grantham Hospital MacLehose Medical Rehabilitation Centre Hong Kong West The Duchess of Kent Children’s Hospital at Sandy Bay Cluster Tung Wah Group of Hospitals Fung Yiu King Hospital Tung Wah Hospital Kowloon East Haven of Hope Hospital Cluster Hong Kong Buddhist Hospital Kowloon Central Kowloon Hospital (Except Psychiatric Wards) Cluster Our Lady of Maryknoll Hospital Tung Wah Group of Hospitals Wong Tai Sin Hospital Caritas Medical Centre Developmental Disabilities Unit, Wai Yee Block Medical and Geriatrics/Orthopaedics Rehabilitation Wards and Palliative Care Ward, Wai Ming Block North Lantau Hospital Kowloon West Extended Care Wards Cluster Princess Margaret Hospital Lai King Building Yan Chai Hospital Orthopaedics and Traumatology Rehabilitation Ward and Medical Extended Care Unit (Rehabilitation and Infirmary Wards), Multi-services Complex New Territories Bradbury Hospice East Cluster Cheshire Home, Shatin North District Hospital 4B Convalescent Rehabilitation Ward Shatin Hospital (Except Psychiatric Wards) Tai Po Hospital (Except Psychiatric Wards) Pok Oi Hospital Tin Ka Ping Infirmary New Territories Siu Lam Hospital West Cluster Tuen Mun Hospital Rehabilitation Block (Except Day Wards) H1 Palliative Ward 2. Hospital staff will contact patients’ family members for explanation of special visiting arrangement and scheduling the visits. -

List of Hospitals That Keep Copies of the Application Form for Reimbursement / Direct Payment of Medical Expenses

List of Hospitals that Keep Copies of the Application Form for Reimbursement / Direct Payment of Medical Expenses Responsible Office / Location / Cluster Hospital Telephone Office Hours Hong Kong Pamela Youde Enquiry Counter / 2595 6205 East Cluster Nethersole G/F., Main Block, Pamela Youde Nethersole Eastern Hospital Eastern Hospital / Monday to Friday 9:00 a.m. to 5:00 p.m. Saturday 9:00 a.m. to 1:00 p.m. Ruttonjee Medical Records Office / 2291 1035 Hospital LG1, Hospital Main Building, Ruttonjee Hospital / Monday to Friday 9:00 a.m. to 5:30 p.m. Saturday 9:00 a.m. to 12:00 noon St. John Hospital Personnel Office / 2981 9442 2/F., OPD Block, St. John Hospital / Monday to Friday 9:00 a.m. to 1:00 p.m. 2:00 p.m. to 5:00 p.m. Hong Kong Queen Mary Health Information & Records Office / 2855 4175 West Cluster Hospital 2/F., Block S, Queen Mary Hospital / Monday to Friday 9:00 a.m. to 1:00 p.m. 2:00 p.m. to 5:00 p.m. Saturday 9:00 a.m. to 1:00 p.m. Grantham Patient Relations Officer / 2518 2182 Hospital 1/F., Kwok Tak Seng Heart Centre, Grantham Hospital / Monday to Friday 9:00 a.m. to 5:00 p.m. Saturday 9:00 a.m. to 1:00 p.m. - 2 - Responsible Office / Location / Cluster Hospital Telephone Office Hours Kowloon Kwong Wah Medical Report Office / 3517 5216 West Cluster Hospital 1/F., Central Stack, Kwong Wah Hospital / Monday to Friday 9:00 a.m. -

Hospital Authority List of Medical Social Services Units (January 2019)

Hospital Authority List of Medical Social Services Units (January 2019) Name of Hospital Address Tel No. Fax No. 1. Alice Ho Miu Ling Nethersole 11 Chuen On Road, Tai Po, N.T. 2689 2020 2662 3152 Hospital (Non- psychiatric medical social service) 2. Bradbury Hospital 17 A Kung Kok Shan Road, 2645 8832 2762 1518 Shatin, N.T. 3. Caritas Medical Centre 111 Wing Hong Street, 3408 7709 2785 3192 Shamshuipo, Kowloon 4. Cheshire Home 128 Chung Hom Kok Road, 2899 1391 2813 8752 (Chung Hom Kok) Hong Kong 5. Cheshire Home (Shatin) 30 A Kung Kok Shan Road, 2636 7269 2636 7242 Shatin, N.T. 6. TWGHs Fung Yiu King Hospital 9 Sandy Bay Road, Hong Kong 2855 6236 2904 9021 7. Grantham Hospital 125 Wong Chuk Hang Road, 2518 2678 2580 7629 Aberdeen, Hong Kong 8. Haven of Hope Hospital 8 Haven of Hope Road, 2703 8227 2703 8230 Tseung Kwan O, Kowloon 9. Hong Kong Buddhist Hospital 10 Heng Lam Road, Lok Fu, 2339 6253 2339 6298 Kowloon 10. Kowloon Hospital Mezzanine Floor, Kowloon 3129 7806/ 3129 7838 (Ward 2B at Rehabilitation Hospital Rehabilitation Building, 3129 7831 Building ) 147A, Argyle Street, Kowloon 11. Kwong Wah Hospital 25 Waterloo Road, Kowloon 3517 2900 3517 2959 12. MacLehose Medical 7 Sha Wan Drive, 2872 7131 2872 7909 Rehabilitation Centre Pokfulam, Hong Kong Name of Hospital Address Tel No. Fax No. 13. Our Lady of Maryknoll Hospital 118 Shatin Pass Road, 2354 2285 2324 8719 Wong Tai Sin, Kowloon 14. Pok Oi Hospital Au Tau, Yuen Long, N.T. 2486 8140 2486 8095 2486 8141 15. -

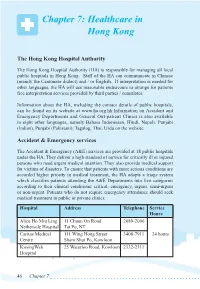

Chapter 7: Healthcare in Hong Kong

Chapter 7: Healthcare in Hong Kong The Hong Kong Hospital Authority The Hong Kong Hospital Authority (HA) is responsible for managing all local public hospitals in Hong Kong. Staff of the HA can communicate in Chinese (mainly the Cantonese dialect) and / or English. If interpretation is needed for other languages, the HA will use reasonable endeavours to arrange for patients free interpretation services provided by third parties / consulates. Information about the HA, including the contact details of public hospitals, can be found on its website at www.ha.org.hk.Information on Accident and Emergency Departments and General Out-patient Clinics is also available in eight other languages, namely Bahasa Indonesian, Hindi, Nepali, Punjabi (Indian), Punjabi (Pakistani), Tagalog, Thai, Urdu on the website. Accident & Emergency services The Accident & Emergency (A&E) services are provided at 18 public hospitals under the HA. They deliver a high standard of service for critically ill or injured persons who need urgent medical attention. They also provide medical support for victims of disasters. To ensure that patients with more serious conditions are accorded higher priority in medical treatment, the HA adopts a triage system which classifies patients attending the A&E Departments into five categories according to their clinical conditions: critical, emergency, urgent, semi-urgent or non-urgent. Patients who do not require emergency attendance should seek medical treatment in public or private clinics. Hospital Address Telephone Service Hours Alice Ho Miu Ling 11 Chuen On Road 2689-2000 Nethersole Hospital Tai Po, NT Caritas Medical 111 Wing Hong Street 3408-7911 24 hours Centre Sham Shui Po, Kowloon KwongWah 25 Waterloo Road, Kowloon 2332-2311 Hospital 46 Chapter 7 North District 9 Po Kin Road 2683-8888 Hospital Sheung Shui, NT North Lantau 1/F, 8 Chung Yan Road 3467-7000 Hospital Tung Chung, Lantau, N.T. -

List of Medical Social Services Units Under Social Welfare Department

List of Medical Social Services Units Under Social Welfare Department Hong Kong Name of Hospital/Clinic Tel. No. Email Address 1. Queen Mary Hospital 2255 3762 [email protected] 2255 3764 2. Wong Chuk Hang Hospital 2873 7201 [email protected] 3. Pamela Youde Nethersole Eastern 2595 6262 [email protected] Hospital 4. Pamela Youde Nethersole Eastern 2595 6773 [email protected] Hospital (Psychiatric Department) Kowloon Name of Hospital/Clinic Tel. No. Email Address 5. Tseung Kwan O Hospital 2208 0335 [email protected] 2208 0327 6. United Christian Hospital 3949 5178 [email protected] (Psychiatry) 7. Queen Elizabeth Hospital 3506 7021 [email protected] 3506 7027 3506 5499 3506 4021 8. Hong Kong Eye Hospital 2762 3069 [email protected] 9. Kowloon Hospital Rehabilitation 3129 7857 [email protected] Building 10. Kowloon Hospital 3129 6193 [email protected] 11. Kowloon Hospital 2768 8534 [email protected] (Psychiatric Department) 1 The New Territories Name of Hospital/Clinic Tel. No. Email Address 12. Prince of Wales Hospital 3505 2400 [email protected] 13. Shatin Hospital 3919 7521 [email protected] 14. Tai Po Hospital 2607 6304 [email protected] Sub-office Tai Po Hospital (Child and Adolescent 2689 2486 [email protected] Mental Health Centre) 15. North District Hospital 2683 7750 [email protected] 16. Tin Shui Wai Hospital 3513 5391 [email protected] 17. Castle Peak Hospital 2456 7401 [email protected] 18. Siu Lam Hospital 2456 7186 [email protected] 19. -

TOWN PLANNING BOARD Minutes of 390Th Meeting of the Metro Planning Committee Held at 9:00 A.M. on 13.2.2009 Present Director O

TOWN PLANNING BOARD Minutes of 390th Meeting of the Metro Planning Committee held at 9:00 a.m. on 13.2.2009 Present Director of Planning Chairperson Mrs. Ava S.Y. Ng Mr. Stanley Y.F. Wong Vice-chairman Mr. Nelson W.Y. Chan Mr. Leslie H.C. Chen Professor N.K. Leung Dr. Daniel B.M. To Ms. Sylvia S.F. Yau Mr. Walter K.L. Chan Mr. Raymond Y.M. Chan Ms. Starry W.K. Lee Mr. K.Y. Leung Mr. Maurice W.M. Lee Dr. Winnie S.M. Tang Assistant Commissioner for Transport (Urban), Transport Department Mr. Anthony Loo Assistant Director (Environmental Assessment), - 2 - Environmental Protection Department Mr. C.W. Tse Assistant Director (Kowloon), Lands Department Ms. Olga Lam Deputy Director of Planning/District Secretary Miss Ophelia Y.S. Wong Absent with Apologies Professor Bernard V.W.F. Lim Mr. Felix W. Fong Dr. Ellen Y.Y. Lau Assistant Director(2), Home Affairs Department Mr. Andrew Tsang In Attendance Assistant Director of Planning/Board Mr. Lau Sing Chief Town Planner/Town Planning Board Mr. W.S. Lau Town Planner/Town Planning Board Ms. Karina W.M. Mok - 3 - Agenda Item 1 Confirmation of the Draft Minutes of the 389th MPC Meeting Held on 23.1.2009 [Open Meeting] 1. The draft minutes of the 389th MPC meeting held on 23.1.2009 were confirmed without amendments. Agenda Item 2 Matters Arising [Open Meeting] (i) Approval of Outline Zoning Plans (OZPs) 2. The Secretary reported that the Chief Executive in Council (CE in C) on 10.2.2009 had approved the draft Ting Kok OZP (to be renumbered as S/NE-TK/15) and the draft Peng Chau OZP (to be renumbered as S/I-PC/10) under section (9)(1)(a) of the Town Planning Ordinance (the Ordinance).