Will I Ever Be Enough?

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Digital Feminism in the Arab Gulf

MIT Center for Intnl Studies | Starr Forum: Digital Feminism in the Arab Gulf MICHELLE I'm Michelle English, and on behalf of the MIT Center for International Studies, welcome you to ENGLISH: today's Starr Forum. Before we get started, I'd like to mention that this is our last planned event for the fall. However, we do have many, many events planned for the spring. So if you haven't already, please take time to sign up to get our event notices. Today's talk on digital feminism in the Arab Gulf states is co-sponsored by the MIT Women's and Gender Studies program, the MIT History department, and the MIT Press bookstore. In typical fashion, our talk will conclude with Q&A with the audience. And for those asking questions, please line up behind the microphones. We ask that you to be considerate of time and others who want to ask questions. And please also identify yourself and your affiliation before asking your question. Our featured speaker is Mona Eltahawy, an award winning columnist and international public speaker on Arab and Muslim issues and global feminism. She is based in Cairo and New York City. Her commentaries have appeared in multiple publications and she is a regular guest analyst on television and radio shows. During the Egypt Revolution in 2011, she appeared on most major media outlets, leading the feminist website Jezebel to describe her as the woman explaining Egypt to the West. In November 2011, Egyptian riot police beat her, breaking her left arm and right hand, and sexually assaulted her, and she was detained for 12 hours by the Interior Ministry and Military Intelligence. -

Iranian Women's Quest for Self-Liberation Through

IRANIAN WOMEN’S QUEST FOR SELF-LIBERATION THROUGH THE INTERNET AND SOCIAL MEDIA: AN EMANCIPATORY PEDAGOGY TANNAZ ZARGARIAN A DISSERTATION SUBMITTED TO THE FACULTY OF GRADUATE STUDIES IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY GRADUATE PROGRAM IN EDUCATION YORK UNIVERSITY TORONTO, ONTARIO December 2019 © [Tannaz Zargarian, 2019] i Abstract This dissertation examines the discourse of body autonomy among Iranian women. It approaches the discourse of body autonomy by deconstructing veiling, public mobility, and sexuality, while considering the impact of society, history, religion, and culture. Although there are many important scholarly works on Iranian women and human rights that explore women’s civil rights and freedom of individuality in relation to the hijab, family law, and sexuality, the absence of work on the discourse of body autonomy—the most fundamental human right—has created a deficiency in the field. My research examines the discourse of body autonomy in the context of liberation among Iranian women while also assessing the role of the internet as informal emancipatory educational tools. To explore the discourse of body autonomy, I draw upon critical and transnational feminist theory and the theoretical frameworks of Derayeh, Foucault, Shahidian, Bayat, Mauss, and Freire. Additionally, in-depth semi-structured interviews with Iranian women aged 26 to 42 in Iran support my analysis of the practice and understanding of body autonomy personally, on the internet, and social media. The results identify and explicate some of the major factors affecting the practice and awareness of body autonomy, particularly in relation to the goal of liberation for Iranian women. -

Iranian National Commission for Unesco Internationa

UNITED NATIONS ORGANIZATION FOR EDUCATION, SCIENCE AND CULTURE (U N E S C O) IRANIAN NATIONAL COMMISSION FOR UNESCO INTERNATIONAL SYMPOSIUM ON WOMEN’S ROLE IN TRANSMISSION OF INTANGIBLE CULTURAL HERITAGE Tehran, Iran, 27 - 30 September 1999 LIST OF PARTICIPANTS _____________ Bahrain Ms Aisha Matar Director Modern Craft Industries Co. 263 Isa Al-Kabeer Road Manama 309 Bahrain Tel: 973 25 46 88 / 530 106 Fax: 973 24 66 15 Paper: Modern Craft Industries Project in Bahrain Finland Prof. Pirkko Moisala Department of Musicology Sibelius Museum Abo Akademi University Biskopsgatan 17, FIN-20500 Abo Finland Tel: + 358 2358 2 215 43 38 Fax: + 358 2 251 8528 Email: [email protected] Paper: The Role of Women in the Oral Transmission of Music - Examples from Nepal and Finland 2 Ghana Mama Adokuwa-Asigble IV c/o 31st Dec. Women’s Movement P.O. Box O.65, Osu Accra, Ghana Tel: + 233 21 221 470 Fax: + 233 21 220 303 Paper: Puberty Rights and Adulthood: The Rôle of Women in Transmitting Cutlural Values Ms Rejoice Abla Dugbazah Linguist C/o 31st Dec. Women’s Movement P.O. Box O.65, Osu Accra, Ghana Tel: + 233 21 221 470 Fax: + 233 21 220 303 Hungary Professor M Hoppal European Folklore Institute HUNGARY - 1011 Budapest Szilagi D, ter 6 Tel/Fax: + 36 1 212 20 39 Home: + 36 1 201 62 37 Email: [email protected] Paper: The Role of Women in the Transmission of Folklore - Local Cultures in a Global World India Ms Maya Rao A-30 Friends Colony East New Delhi 110065 India Tel/Fax: 91 1169 27 691 E.mail: [email protected] Paper: no paper, oraldescribing the Indian traditional performance art of Kathakali, and her experiences as a mother Indonesia Prof. -

Modernizing the Public Space: Gender Identities

MODERNIZING THE PUBLIC SPACE: GENDER IDENTITIES, MULTIPLE MODERNITIES, AND SPACE POLITICS IN TEHRAN A DISSERTATION IN Geosciences and Sociology Presented to the Faculty of the University of Missouri-Kansas City in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY by NAZGOL BAGHERI Bachelor of Architecture, 2004 Bachelor of Computer Science, 2006 Master of Urban Design, 2007 Shahid Beheshti University, Tehran, Iran Kansas City, Missouri 2013 © 2013 NAZGOL BAGHERI ALL RIGHTS RESERVED MODERNIZING THE PUBLIC SPACE: GENDER IDENTITIES, MULTIPLE MODERNITIES, AND SPACE POLITICS IN TEHRAN Nazgol Bagheri, Candidate for the Doctor of Philosophy Degree University of Missouri - Kansas City, 2013 ABSTRACT After the Islamic Revolution of 1979 in Iran, surprisingly, the presence of Iranian women in public spaces dramatically increased. Despite this recent change in women’s presence in public spaces, Iranian women, like in many other Muslim-majority societies in the Middle East, are still invisible in Western scholarship, not because of their hijabs but because of the political difficulties of doing field research in Iran. This dissertation serves as a timely contribution to the limited post-revolutionary ethnographic studies on Iranian women. The goal, here, is not to challenge the mainly Western critics of modern and often privatized public spaces, but instead, is to enrich the existing theories through including experiences of a more diverse group. Focusing on the women’s experience, preferences, and use of public spaces in Tehran through participant observation and interviews, photography, architectural sketching as well as GIS spatial analysis, I have painted a picture of the complicated relationship between the architecture styles, the gendering of spatial boundaries, and the contingent nature of public spaces that goes beyond the simple dichotomy of female- male, private-public, and modern-traditional. -

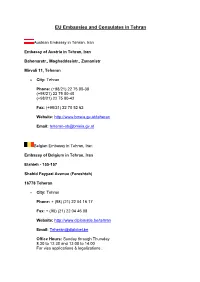

EU Embassies and Consulates in Tehran

EU Embassies and Consulates in Tehran Austrian Embassy in Tehran, Iran Embassy of Austria in Tehran, Iran Bahonarstr., Moghaddasistr., Zamanistr Mirvali 11, Teheran City: Tehran Phone: (+98/21) 22 75 00-38 (+98/21) 22 75 00-40 (+98/21) 22 75 00-42 Fax: (+98/21) 22 70 52 62 Website: http://www.bmeia.gv.at/teheran Email: [email protected] Belgian Embassy in Tehran, Iran Embassy of Belgium in Tehran, Iran Elahieh - 155-157 Shahid Fayyazi Avenue (Fereshteh) 16778 Teheran City: Tehran Phone: + (98) (21) 22 04 16 17 Fax: + (98) (21) 22 04 46 08 Website: http://www.diplomatie.be/tehran Email: [email protected] Office Hours: Sunday through Thursday 8.30 to 12.30 and 13.00 to 14.00 For visa applications & legalizations : Sunday through Tuesday from 8.30 to 11.30 AM Bulgarian Embassy in Tehran, Iran Bulgarian Embassy in Tehran, Iran IR Iran, Tehran, 'Vali-e Asr' Ave. 'Tavanir' Str., 'Nezami-ye Ganjavi' Str. No. 16-18 City: Tehran Phone: (009821) 8877-5662 (009821) 8877-5037 Fax: (009821) 8877-9680 Email: [email protected] Croatian Embassy in Tehran, Iran Embassy of the Republic of Croatia in Tehran, Iran 1. Behestan 25 Avia Pasdaran Tehran, Islamic Republic of Iran City: Tehran Phone: 0098 21 258 9923 0098 21 258 7039 Fax: 0098 21 254 9199 Email: [email protected] Details: Covers the Islamic Republic of Pakistan, Islamic Republic of Afghanistan Details: Ambassador: William Carbó Ricardo Cypriot Embassy in Tehran, Iran Embassy of the Republic of Cyprus in Tehran, Iran 328, Shahid Karimi (ex. -

PROTESTS and REGIME SUPPRESSION in POST-REVOLUTIONARY IRAN Saeid Golkar

THE WASHINGTON INSTITUTE FOR NEAR EAST POLICY n OCTOBER 2020 n PN85 PROTESTS AND REGIME SUPPRESSION IN POST-REVOLUTIONARY IRAN Saeid Golkar Green Movement members tangle with Basij and police forces, 2009. he nationwide protests that engulfed Iran in late 2019 were ostensibly a response to a 50 percent gasoline price hike enacted by the administration of President Hassan Rouhani.1 But in little time, complaints Textended to a broader critique of the leadership. Moreover, beyond the specific reasons for the protests, they appeared to reveal a deeper reality about Iran, both before and since the 1979 emergence of the Islamic Republic: its character as an inherently “revolutionary country” and a “movement society.”2 Since its formation, the Islamic Republic has seen multiple cycles of protest and revolt, ranging from ethnic movements in the early 1980s to urban riots in the early 1990s, student unrest spanning 1999–2003, the Green Movement response to the 2009 election, and upheaval in December 2017–January 2018. The last of these instances, like the current round, began with a focus on economic dissatisfaction and then spread to broader issues. All these movements were put down by the regime with characteristic brutality. © 2020 THE WASHINGTON INSTITUTE FOR NEAR EAST POLICY. ALL RIGHTS RESERVED. SAEID GOLKAR In tracking and comparing protest dynamics and market deregulation, currency devaluation, and the regime responses since 1979, this study reveals that cutting of subsidies. These policies, however, spurred unrest has become more significant in scale, as well massive inflation, greater inequality, and a spate of as more secularized and violent. -

MENA Women News Briefdownload

May 29: Afghan women denied justice over violence, United Nations says “A law meant to protect Afghan women from violence is being undermined by authorities who routinely refer even serious criminal cases to traditional mediation councils that fail to protect victims, the United Nations said on Tuesday. The Elimination of Violence against Women (EVAW) law, passed in 2009, was a centerpiece of efforts to improve protection for Afghan women, who suffer widespread violence in one of the worst countries in the world to be born female.” (Reuters) May 31: Female Genital Mutilation is Declared Religiously Forbidden in Islam “Egyptian Dar Al-Iftaa declared that female genital mutilation (FGM) is religiously forbidden on May 30, 2018, adding that banning FGM should be a religious duty due to its harmful effects on the body. Dar Al- Iftaa also explained that FGM is not mentioned in Islamic laws and that it only still occurs because it’s considered to be a social norm in the rural areas and some poor parts of Egypt. FGM is considered as an attack on religion through damaging the most sensitive organ in the female body. In Islam, protecting the body from any harm is a must and mutilation violates this rule.” (Egypt Today) June 4: Government proposes new draft law to ban early marriage “Egypt's government has proposed a new draft law that includes amendments to the child law article 12 of 1996, which states cases in which parents could be deprived from the authority of guardianship over the girl or her property…Hawary told Egypt Today that this bill stipulates that a father who forces his daughter to get married before reaching the age of marriage will be deprived from the authority of guardianship over the girl or her property.” (Egypt Today) June 4: Youth, women, and minorities have valid concerns “Iranian President Hassan Rouhani admitted on Friday that the youth, women and minorities have legitimate grievances, Anadolu Agency reported, citing the Iranian presidency’s official website. -

Active Tectonics of Tehran Area, Iran

J. Basic. Appl. Sci. Res., 2(4)3805-3819, 2012 ISSN 2090-4304 Journal of Basic and Applied © 2012, TextRoad Publication Scientific Research www.textroad.com Active Tectonics of Tehran Area, Iran Mehran Arian1 *, Nooshin Bagha2 1Associate professor, Department of Geology, Science and Research branch, Islamic Azad University, Tehran, Iran 2Ph.D.Student, Department of Geology, Science and Research branch, Islamic Azad University, Tehran, Iran ABSTRACT Tehran area (with 2398.5 km2 area) extended from the east of Damavand volcano to the west of Karaj city. This area is a major part of Tehran province and according to geologic division is a minor part of Alborz zone. This area is under compressive stress and shortening that caused by Arabia – Eurasia Convergence. This situation has confirmed by dominant existence of folded structures and thrust fault system. We have investigated geologic hazards of Tehran area, because this area is the most strategic part of Iran. The major faults have been investigated and have not been found any evidences to existence of north and south Rey faults. In the other hand, active tectonic of this area has been investigated and Mosha fault has been introduced as the most active fault. The high seismic potential has been distinguished by integration of structural geology and active tectonic studies. The evaluation of movement potential of the main faults in the current tectonic regime shows the North Tehran fault has % 90 potential to movement. In addition the hazard potentials of landslides, settlements, volcanism and dams have been introduced. Finally, geologic hazard map has been prepared and has been divided to10 zones with one to four ranking of risk. -

The Muslim 500 2011

The Muslim 500 � 2011 The Muslim The 500 The Muslim 500 � 2011 The Muslim The 500 The Muslim 500The The Muslim � 2011 500———————�——————— THE 500 MOST INFLUENTIAL MUSLIMS ———————�——————— � 2 011 � � THE 500 MOST � INFLUENTIAL MUSLIMS · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · All rights reserved. No part of this book may be repro- The Muslim 500: The 500 Most Influential Muslims duced or utilised in any form or by any means, electronic 2011 (First Edition) or mechanic, inclding photocopying or recording or by any ISBN: 978-9975-428-37-2 information storage and retrieval system, without the prior · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · written permission of the publisher. Views expressed in The Muslim 500 do not necessarily re- Chief Editor: Prof. S. Abdallah Schleifer flect those of RISSC or its advisory board. Researchers: Aftab Ahmed, Samir Ahmed, Zeinab Asfour, Photo of Abdul Hakim Murad provided courtesy of Aiysha Besim Bruncaj, Sulmaan Hanif, Lamya Al-Khraisha, and Malik. Mai Al-Khraisha Image Copyrights: #29 Bazuki Muhammad / Reuters (Page Designed & typeset by: Besim Bruncaj 75); #47 Wang zhou bj / AP (Page 84) Technical consultant: Simon Hart Calligraphy and ornaments throughout the book used courtesy of Irada (http://www.IradaArts.com). Special thanks to: Dr Joseph Lumbard, Amer Hamid, Sun- dus Kelani, Mohammad Husni Naghawai, and Basim Salim. English set in Garamond Premiere -

Sheikh Qassim, the Bahraini Shi'a, and Iran

k o No. 4 • July 2012 o l Between Reform and Revolution: Sheikh Qassim, t the Bahraini Shi’a, and Iran u O By Ali Alfoneh The political stability of the small island state of Bahrain—home to the US Navy’s Fifth Fleet—matters to the n United States. And Sheikh Qassim, who simultaneously leads the Bahraini Shi’a majority’s just struggle for a more r democratic society and acts as an agent of the Islamic Republic of Iran, matters to the future of Bahrain. A survey e of the history of Shi’a activism in Bahrain, including Sheikh Qassim’s political life, shows two tendencies: reform and t revolution. Regardless of Sheikh Qassim’s dual roles and the Shi’a protest movement’s periodic ties to the regime in Tehran, the United States should do its utmost to reconcile the rulers and the ruled in Bahrain by defending the s civil rights of the Bahraini Shi’a. This action would not only conform to the United States’ principle of promoting a democracy and human rights abroad, but also help stabilize Bahrain and the broader Persian Gulf region and under- mine the ability of the regime in Tehran to continue to exploit the sectarian conflict in Bahrain in a way that broadens E its sphere of influence and foments anti-Americanism. e Every Friday, the elderly Ayatollah Isa Ahmad The Sunni ruling elites of Bahrain, however, l Qassim al-Dirazi al-Bahrani, more commonly see Sheikh Qassim not as a reformer but as d known as Sheikh Qassim, climbs the stairs to the a zealous revolutionary serving the Islamic pulpit at the Imam al-Sadiq mosque in Diraz, d Bahrain, to deliver his sermon. -

Federal Register/Vol. 85, No. 63/Wednesday, April 1, 2020/Notices

18334 Federal Register / Vol. 85, No. 63 / Wednesday, April 1, 2020 / Notices DEPARTMENT OF THE TREASURY a.k.a. CHAGHAZARDY, MohammadKazem); Subject to Secondary Sanctions; Gender DOB 21 Jan 1962; nationality Iran; Additional Male; Passport D9016371 (Iran) (individual) Office of Foreign Assets Control Sanctions Information—Subject to Secondary [IRAN]. Sanctions; Gender Male (individual) Identified as meeting the definition of the Notice of OFAC Sanctions Actions [NPWMD] [IFSR] (Linked To: BANK SEPAH). term Government of Iran as set forth in Designated pursuant to section 1(a)(iv) of section 7(d) of E.O. 13599 and section AGENCY: Office of Foreign Assets E.O. 13382 for acting or purporting to act for 560.304 of the ITSR, 31 CFR part 560. Control, Treasury. or on behalf of, directly or indirectly, BANK 11. SAEEDI, Mohammed; DOB 22 Nov ACTION: Notice. SEPAH, a person whose property and 1962; Additional Sanctions Information— interests in property are blocked pursuant to Subject to Secondary Sanctions; Gender SUMMARY: The U.S. Department of the E.O. 13382. Male; Passport W40899252 (Iran) (individual) Treasury’s Office of Foreign Assets 3. KHALILI, Jamshid; DOB 23 Sep 1957; [IRAN]. Control (OFAC) is publishing the names Additional Sanctions Information—Subject Identified as meeting the definition of the of one or more persons that have been to Secondary Sanctions; Gender Male; term Government of Iran as set forth in Passport Y28308325 (Iran) (individual) section 7(d) of E.O. 13599 and section placed on OFAC’s Specially Designated [IRAN]. 560.304 of the ITSR, 31 CFR part 560. Nationals and Blocked Persons List Identified as meeting the definition of the 12. -

A NEW DIRECTION for CHICK LIT by Rachel

ABSTRACT CONSCIOUSNESS-RAISING: A NEW DIRECTION FOR CHICK LIT by Rachel R. Rode Schaefer Focusing on novels published outside of the popular market, this thesis seeks to draw attention to work being published under the label of chick lit that subverts standard chick lit genre conventions. While much work has been and is being done that concentrates on popular market chick lit, such as Helen Fielding’s Bridget Jones’s Diary (1996) and Candace Bushnell’s Sex and the City (1996), only cursory attention is being given to transnational, minority, and religious chick lit. This thesis considers chick lit within the larger history of women’s writing in order to contextualize the genre. Since chick lit has been connected to both feminism and post-feminism in its origins, consideration of this genre as a feminist genre focuses attention on how chick lit functions as a consciousness-raising genre. CONSCIOUSNESS-RAISING: A NEW DIRECTION FOR CHICK LIT A Thesis Submitted to the Faculty of Miami University In partial fulfillment of Master of Arts Department of English by Rachel R. Rode Schaefer Miami University Oxford, Ohio 2015 Advisor_________________________________ Dr. Madelyn Detloff Reader__________________________________ Dr. Mary Jean Corbett Reader__________________________________ Dr. Theresa Kulbaga © Rachel R. Rode Schaefer 2015 Table of Contents Introduction: Reading Chick Lit as Consciousness-Raising Novel ................................................ 1 Project Summary ........................................................................................................................