The Tragic Crisis for Wotan in Wagner's Ring Cycle Dr. Adrian Anderson

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Wagner in Comix and 'Toons

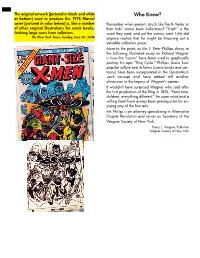

- The original artwork [pictured in black and white Who Knew? at bottom] used to produce the 1975 Marvel cover [pictured in color below] is, like a number Remember when parents struck like Darth Vader at of other original illustrations for comic books, their kids’ comic book collections? “Trash” is the fetching large sums from collectors. word they used, and out the comics went. Little did The New York Times, Sunday, June 30, 2008 anyone realize that he might be throwing out a valuable collectors piece. More to the point, as Mr. F. Peter Phillips shows in the following illustrated essay on Richard Wagner is how the “comix” have been used to graphically portray his epic “Rng Cycle.” Phillips shows how popular culture and its forms (comic books and car- toons) have been incorporated in the Gesamtkust- werk concept and have added still another dimension to the legacy of Wagner’s operas. It wouldn’t have surprised Wagner who said after the first production of the Ring in 1876, “Next time, children, everything different.” An open mind and a willing heart have always been prerequisites for en- joying any of the fine arts. Mr. Phllips is an attorney specializing in Alternative Dispute Resolution and serves as Secretary of the Wagner Society of New York. Harry L. Wagner, Publisher Wagner Society of New York Wagner in Comix and ‘Toons By F. Peter Phillips Recent publications have revealed an aspect of Wagner-inspired literature that has been grossly overlooked—Wagner in graphic art (i.e., comics) and in animated cartoons. The Ring has been ren- dered into comics of substantial integrity at least three times in the past two decades, and a recent scholarly study of music used in animated cartoons has noted uses of Wagner’s music that suggest that Wagner’s influence may even more profoundly im- bued in our culture than we might have thought. -

Relationality and Masculinity in Superhero Narratives Kevin Lee Chiat Bachelor of Arts (Communication Studies) with Second Class Honours

i Being a Superhero is Amazing, Everyone Should Try It: Relationality and Masculinity in Superhero Narratives Kevin Lee Chiat Bachelor of Arts (Communication Studies) with Second Class Honours This thesis is presented for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy of The University of Western Australia School of Humanities 2021 ii THESIS DECLARATION I, Kevin Chiat, certify that: This thesis has been substantially accomplished during enrolment in this degree. This thesis does not contain material which has been submitted for the award of any other degree or diploma in my name, in any university or other tertiary institution. In the future, no part of this thesis will be used in a submission in my name, for any other degree or diploma in any university or other tertiary institution without the prior approval of The University of Western Australia and where applicable, any partner institution responsible for the joint-award of this degree. This thesis does not contain any material previously published or written by another person, except where due reference has been made in the text. This thesis does not violate or infringe any copyright, trademark, patent, or other rights whatsoever of any person. This thesis does not contain work that I have published, nor work under review for publication. Signature Date: 17/12/2020 ii iii ABSTRACT Since the development of the superhero genre in the late 1930s it has been a contentious area of cultural discourse, particularly concerning its depictions of gender politics. A major critique of the genre is that it simply represents an adolescent male power fantasy; and presents a world view that valorises masculinist individualism. -

D. H. Lawrence and the Harlem Renaissance

‘You are white – yet a part of me’: D. H. Lawrence and the Harlem Renaissance A thesis submitted to The University of Manchester for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Faculty of Humanities 2019 Laura E. Ryan School of Arts, Languages and Cultures 2 Contents Abstract ...................................................................................................................... 3 Declaration ................................................................................................................. 4 Copyright statement ................................................................................................... 5 Acknowledgements .................................................................................................... 6 Introduction ................................................................................................................ 7 Chapter 1: ‘[G]roping for a way out’: Claude McKay ................................................ 55 Chapter 2: Chaos in Short Fiction: Langston Hughes ............................................ 116 Chapter 3: The Broken Circle: Jean Toomer .......................................................... 171 Chapter 4: ‘Becoming [the superwoman] you are’: Zora Neale Hurston................. 223 Conclusion ............................................................................................................. 267 Bibliography ........................................................................................................... 271 Word Count: 79940 3 -

Contents Humanities Notes

Humanities Notes Humanities Seminar Notes - this draft dated 24 May 2021 - more recent drafts will be found online Contents 1 2007 11 1.1 October . 11 1.1.1 Thucydides (2007-10-01 12:29) ........................ 11 1.1.2 Aristotle’s Politics (2007-10-16 14:36) ..................... 11 1.2 November . 12 1.2.1 Polybius (2007-11-03 09:23) .......................... 12 1.2.2 Cicero and Natural Rights (2007-11-05 14:30) . 12 1.2.3 Pliny and Trajan (2007-11-20 16:30) ...................... 12 1.2.4 Variety is the Spice of Life! (2007-11-21 14:27) . 12 1.2.5 Marcus - or Not (2007-11-25 06:18) ...................... 13 1.2.6 Semitic? (2007-11-26 20:29) .......................... 13 1.2.7 The Empire’s Last Chance (2007-11-26 20:45) . 14 1.3 December . 15 1.3.1 The Effect of the Crusades on European Civilization (2007-12-04 12:21) 15 1.3.2 The Plague (2007-12-04 14:25) ......................... 15 2 2008 17 2.1 January . 17 2.1.1 The Greatest Goth (2008-01-06 19:39) .................... 17 2.1.2 Just Justinian (2008-01-06 19:59) ........................ 17 2.2 February . 18 2.2.1 How Faith Contributes to Society (2008-02-05 09:46) . 18 2.3 March . 18 2.3.1 Adam Smith - Then and Now (2008-03-03 20:04) . 18 2.3.2 William Blake and the Doors (2008-03-27 08:50) . 19 2.3.3 It Must Be True - I Saw It On The History Channel! (2008-03-27 09:33) . -

DC Earth 2 Jumpchain

DC Earth 2 Jumpchain Five years ago, the Apokolips War ravaged the Earth. Boom Tubes opened across the world, Parademons led by the New God Steppenwolf swarmed and overran the armies of Earth, and countless innocents died in the crossfire. Only through the bravery and sacrifice of the Ternion, Superman, Batman, and Wonder Woman, were the Boom Tubes closed, ending the war and stranding Steppenwolf and his Parademons on Earth. Humanity had won, but they’d won a pyrrhic victory. Wonder Woman was dead by Steppenwolf’s hands, Batman was killed disabling the Boom Tubes, and Superman had vanished in a flash of energy after being surrounded by Parademons. Supergirl and Robin disappeared into thin air, and Wonder Woman’s daughter was being raised by Steppenwolf himself as his Fury. The world was saved, but at the cost of it’s defenders and heroes. Today, the world still hasn’t recovered. The mysterious fire-pits across the planet spew flames of deadly exotic energy out into space, while many countries were reduced to mere cratered wastelands in the fighting. Steppenwolf and Fury are still at large, and rogue Parademon cells are being uncovered to this day. Terry Sloan, the man who secretly led Apokolips to this dimension in an attempt to save his own homeworld from destruction, is rising in power within the World Army. However, even as Apokolips approaches once more, not all is lost. New heroes, new Wonders, will soon rise to stand against the invaders. Will you join them in defense of the Earth, fall in with the ranks of Apokolips hoping for safety in servitude, or work alone towards your own ends? You receive 1000 Choice Points to make your fate in this world. -

'Expanded' Rumble Ignacio Acquires First Electric Vehicle Charge Station

February 1, 2019 suwarog’omasuwiini (9) Odd Culture 3 • Health 4-5 • Education 6-7 • Sports 12 CU supports Richard’s Subscription or advertising PRSRT STD information, 970-563-0118 tuition bill trophy elk U.S. POSTAGE PAID Ignacio, CO 81137 $29 one year subsciption Permit No. 1 $49 two year subscription PAGE 6 PAGE 13 February 26, 2021 Vol. LIII, No. 4 BOBCATS WRESTLING EDUCATION Wrestlers work through Ignacio School District ‘expanded’ Rumble welcomes one of their own IHS 0-2 in tourney’s duals, 0-3 for night deKay selected as next superintendent By Joel Priest By McKayla Lee SPECIAL TO THE DRUM THE SOUTHERN UTE DRUM Pandemics can apparent- The Ignacio School Dis- ly make for some strange trict will welcome Chris mat-fellows. deKay as the new superin- And at the rotating La Pla- tendent in July. Current su- ta County bragging-rights perintendent Rocco Fus- triangular known as the chetto is set to retire at the 2021 Riverside Rumble, end of the 2020-2021 school Ignacio High’s wrestlers year. “I’m very confident found themselves hosting that Chris will do a great not only 4A Durango and job, he has my support and 3A Bayfield as automat- Joel Priest/Special to the Drum anything he needs help with ic opponents, but also 3A Ignacio’s Kyle Rima refuses to relinquish the leg of Durango’s he knows how to reach me,” Montezuma-Cortez (co- Miguel Stubbs during the 2021 Riverside Rumble – hosted Fuschetto expressed. op’ing this winter with 2A this season by IHS – on Thursday, Feb. -

Der Ring Des Nibelungen the Ring of the Nibelung

1 2 Der Ring des Nibelungen The Ring of the Nibelung Ein Bühnesfestspiel für drei Tage und einen Vorabend A Festival Stage Play for Three Days and a Preliminary Evening 1. Das Rheingold 9th & 23rd February 2014 2. Die Walküre 11th & 25th February 2014 3. Siegfried 12th & 28th February 2014 4. Götterdämmerung 16th February & 2nd March 2014 WELCOME TO THE FULHAM RING Good evening. Thank you for coming and supporting perhaps the maddest and most complicated theatrical production ever undertaken by a tiny fringe opera company! The idea was never to do a complete Ring Cycle. After a production of Amahl and the Night Visitors in December 2010, our dear departed friend Robert Presley said to me “Let’s do Rheingold. I wanna be Alberich”. He should have already known at that point not to put such a silly idea in my head! That Rheingold was a remarkable success, to our great surprise, and rather laid down a gauntlet. The idea to revive the shows for full Cycles was that of Fiona Williams a year ago. Between the two of them, along with the support of Zoë South’s wonderfully colourful Brünnhilde, they have caused something wonderful – not to say unlikely – to occur. The productions and the company have grown over the last three years, and I am personally incredibly grateful to every singer, director, board member, crew member, donor and of course, you, the audience for coming and supporting these crazy endeavours. These two week-long productions are the culmination of six weeks rehearsal, as well as 3 years belief on the part of everyone, and they’re all doing it predominantly for love, as they will each only make a share of the ticket sales. -

Archangels-2018-Catalog.Pdf

Conan Savage Tales #4 Ink Wash Art by Gil Kane and Neal Adams. Savage Tales #4 (Marvel Comics, 1974), original artwork for the story, “Night of the Dark god.” Pencils by Gil Kane and Neal Adams with inks by Neal Adams and ink wash by Pablo Marcos. Searching for his childhood sweetheart Mala, Conan returns to the humble home of his birth in Cimmeria, which he finds in ruins. Here, he discovers Mala’s weeping parents who in- form him that their beloved daughter has been taken north, captured by the vicious Vanir. The damsel’s grieving mother looks at Conan and says, “She...spoke often of you...” A dark and tragic tale of nostalgic woe, in the classic Conan tradition. This is a most impressive piece, which has Adams’ unmistak- ble imprint and style all over it and features Conan in every panel with some superb close-up shots, as only the living leg- end himself can do. Ink-wash Conan art is especially tough. Avengers #96 Art by Neal Adams - Great Ronan page. Original artwork from Avengers #96 page 16 (Marvel Comics, 1972), by the living legend himself, Neal Adams (pencils) with ink finishes by Adams, Tom Palmer and Alan Weiss. This is an impressive action page that prominently features the arch villain, Ronan the Accuser as he interrogates a very defiant Rick Jones, who shows the Kree Supremor just exactly what he thinks of him with a powerful jaw shattering blow to his head. Great multiple images of Ronan, who is gaining greatly in popularity especially since his major role in the Guardians of the Galaxy movie (2014) and, even though he was killed off in that film, there is talk of bringing him back for future feature films. -

26 • November 1999 Spotlighting Kirby's Gods $5.95 in the US

#26 • November 1999 THE Spotlighting Kirby’s Gods $5.95 In The US Collector . c n I , s c i m o C C D © & M T s i t n a M , . c n I , s r e t c a r a h C l e v r a M © & M T s u t c a l a G THE ONLY ’ZINE AUTHORIZED BY THE Issue #26 Contents THE KIRBY ESTATE Jack Kirby On: ....................................6 (storytelling, man, God, and Nazis) Judaism .............................................11 (how did Jack’s faith affect his stories?) Jack Kirby’s Hercules ........................15 (this god was the ultimate hedonist) ISSUE #26, NOV. 1999 COLLECTOR A Failure To Communicate: Part 5 ....17 (a look at Journey Into Mystery #111) Kirby’s Golden Age Gods ..................20 (“It’s in the bag, All-Wisest!”) Myth-ing Pieces ................................22 (examining Kirby’s use of mythology) Theology of the New Gods ...............24 (the spiritual side of Jack’s opus) Fountain of Youth .............................30 (Kirby means never growing up) Jack Kirby: Mythmaker ....................31 (from Thor to the Eternals ) Stan Lee Presents: The Fourth World ...34 (pondering the ultimate “What If?”) Centerfold: Thor #144 pencils ...........36 Walt Simonson Interview .................39 (doing his damnedest on New Gods ) The Church of Stan & Jack ...............45 (the Bible & brotherhood, Marvel-style) Speak of the Devil .............................49 (how many times did Jack use him?) Kirby’s Ockhamistic Twist: Galactus ...50 (did the FF really fight God?) The Wisdom of the Watcher ............54 (putting on some weight, Watcher?) Kirby’s Trinity ...................................56 The Inheritance of Highfather ..........57 (Kirby & the Judeo-Christian doctrine) Forever Questioning .........................60 (comments on the Forever People) Life As Heroism ................................62 (is victory really sacrifice?) Classifieds .........................................66 Collector Comments .........................67 • Front cover inks: Vince Colletta ( Thor #134) • New Gods Concept Drawings (circa 1967): Pg. -

Be He Worthy

University of Wisconsin- Eau Claire Department of History Be He Worthy Thor's journey from Edda to Avenger Michael T. Ekenstedt Advising Professor: Robert J. Gough Fall 2012 Copyright for this work is owned by the author. This digital version is published by McIntyre Library, University of Wisconsin – Eau Claire with the consent of the author Abstract There’s just something about heroes. Through time people have followed their exploits through stories, found inspiration through them we learn about ourselves. Their names have changed as time goes on Achilles, Theseus, and Rama. They gave way to superman, batman, and the Hulk. The heroes and gods of our past are just that past but what does it say about a culture when it turns a hero from their past into one the modern world’s mightiest heroes. This paper will explore how Thor made the journey from a god of legends to a modern day superhero. i Table of Contents Abstract i Contents ii Acknowledgments and Dedication iii Introduction 1 1. A crash course in Norse mythology 2 2. From Vikings to Wagner: A history of Thor and Norse imagery and culture 6 3. Time for the Hammer to fall: The comic book rises falls and recovers 12 4: I need a hero: The graphic new life of Thor in a Marvelous universe 23 5. Conclusion and room for expansion 33 Bibliography 37 ii Acknowledgments: Special thanks to Marvel Enterprises for permission to reproduce and use images from their comic lines. Dedication: To my friends, family, coworkers, classmates, students, people trapped in elevators with me, and anyone else who has politely listened to me ramble on about Vikings, comic books, or history at any point over the last quarter century. -

ARCHIE COMICS Random House Adult Blue Omni, Fall 2013 Archie

ARCHIE COMICS Random House Adult Blue Omni, Fall 2013 Archie Comics The Best of Archie Comics 3 Summary: It's Archie's third volume in our all-time Archie Superstars bestselling The Best of Archie Comics graphic novel series, 9781936975617 featuring even more great stories from Archie's eight decades Pub Date: 9/3/13, On Sale Date: 9/3 of excellence! This fun full-color collection of more of Archie's Ages 10 And Up, Grades 5 And Up all-time favorite stories, lovingly hand-selected and $9.99/$10.99 Can. introduced by Archie creators, editors, and historians from 416 pages / FULL-COLOR ILLUSTRATIONS 200,000 pages of material, is a must-have for any Archie fan THROUGHOUT and fans of comics in general, as well as a great introduction Paperback / softback / Digest format paperback to the comics medium! Juvenile Fiction / Comics & Graphic Novels ... Series: The Best Of Archie ComicsTerritory: World Ctn Qty: 1 Author Bio: THE ARCHIE SUPERSTARS are the impressive 5.250 in W | 7.500 in H line-up of talented writers and artists who have brought 133mm W | 191mm H Archie, his friends and his world to life for more than 70 years, from legends such as Dan DeCarlo, Frank Doyle, Harry Lucey, and Bob Montana to recent greats like Dan Parent and Fernando Ruiz, and many more! Random House Adult Blue Omni, Fall 2013 Archie Comics Sabrina the Teenage Witch: The Magic Within 3 Summary: Return to the magic with Sabrina the Teenage Tania del Rio Witch: The Magic Within 3! 9781936975600 Pub Date: 9/10/13, On Sale Date: 9/10 Sabrina and friends become caught up in the secrets of the Ages 10 And Up, Grades 5 And Up Magic Realm, while friendships and relationships are put to the $10.99/$11.99 Can. -

THE SUPERHERO BOOK SH BM 9/29/04 4:16 PM Page 668

SH BM 9/29/04 4:16 PM Page 667 Index Miss Masque, Miss Acts of Vengeance, 390 Adventure Comics #253, A Victory, Nightveil, Owl, Acy Duecey, 4478 586 A Carnival of Comics, 229 Pyroman, Rio Rita, AD Vision, 21, 135, 156 Adventure Comics #432, “A Day in the Life,” 530 Rocketman, Scarlet Adam, 97 446 (ill.) A Distant Soil, 21 Scorpion, Shade, She- Adam, Allen, 117 Adventure Comics #482, A Touch of Silver (1997), 275 Cat, Yankee Girl Adam Strange, 3–4, 317, 441, 180 (ill.) AAA Pop Comics, 323 Academy X, 650 500, 573, 587 Adventurers’ Club, 181 Aardvark-Vanaheim, 105 Acclaim Entertainment, 563, Justice League of Ameri- Adventures in Babysitting, 525 Abba and Dabba, 385 613 ca, member of, 294 Adventures into the Unknown, Abbey, Lynn, 526 Ace, 42 Adamantium, 643 434 Abbott, Bruce, 147 Ace Comics, 160, 378 Adams, Art, 16, 44–45, 107, The Adventures of Aquaman ABC See America’s Best Ace Magazines, 427 254, 503 (1968–1969), 296 Comics (ABC) Ace of Space, 440 Adams, Arthur See Adams, Art Adventures of Batman (TV ABC News, 565 Ace Periodicals, 77 Adams, Jane, 62, 509 series), 491 ABC Warriors, 441 Ace the Bat-Hound, 59, 72, Adams, Lee, 545 The Adventures of Batman and Abhay (Indian superhero), 283 402, 562 Adams, Neal, 22, 25, 26, 32, Robin (1969–1970), 56, 64 Abin Sur, 240, 582 “Aces,” 527 47, 59, 60, 94, 104, 174, The Adventures of Batman and Abner Cadaver, 416 ACG, 42 177, 237, 240, 241, 334, Robin (1994–1997), 56, 67, Abomination, 259–260, 266, Achille le Heel, 342 325, 353, 366, 374, 435, 493 577 Acolytes, 658 445, 485, 502, 503, 519, The Adventures of Bob Hope, Aboriginie Stevie, 583 Acrata (Planet DC), 282 542, 582, 635, 642 103, 502 About Comics, 194 Acrobat, 578 Adapt (Australian superhero), Adventures of Captain Africa, Abra Kadabra, 220, 575 Action #23, 550 283 378 Abrams, J.