The Wasatch Literary Association 1874-1878

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Beyond the Machine 21.0

Beyond the Machine 21.0 The Juilliard School presents Center for Innovation in the Arts Edward Bilous, Founding Director Beyond the Machine 21.0: Emerging Artists and Art Forms New works by composers, VR artists, and performers working with new performance technologies Thursday, May 20, 2021, 7:30pm ET Saturday, May 22, 2021, 2 and 7pm ET Approximate running time: 90 minutes Juilliard’s livestream technology is made possible by a gift in honor of President Emeritus Joseph W. Polisi, building on his legacy of broadening Juilliard’s global reach. Juilliard is committed to the diversity of our community and to fostering an environment that is inclusive, supportive, and welcoming to all. For information on our equity, diversity, inclusion, and belonging efforts, and to see Juilliard's land acknowledgment statement, please visit our website at juilliard.edu. 1 About Emerging Artists and Art Forms The global pandemic has compelled many performing artists to explore new ways of creating using digital technology. However, for students studying at the Center for Innovation in the Arts, working online and in virtual environments is a normal extension of daily classroom activities. This year, the Center for Innovation in the Arts will present three programs featuring new works by Juilliard students and alumni developed in collaboration with artists working in virtual reality, new media, film, and interactive technology. The public program, Emerging Artists and Artforms, is a platform for students who share an interest in experimental art and interdisciplinary collaboration. All the works on this program feature live performances with interactive visual media and sound. -

UC San Diego UC San Diego Electronic Theses and Dissertations

UC San Diego UC San Diego Electronic Theses and Dissertations Title Conducting, Teaching, Curating: Re-channelings of a Percussive Education Permalink https://escholarship.org/uc/item/00x5v9r5 Author Hepfer, Jonathan David Publication Date 2016 Peer reviewed|Thesis/dissertation eScholarship.org Powered by the California Digital Library University of California UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA, SAN DIEGO Conducting, Teaching, Curating: Re-channelings of a Percussive Education A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree Doctor of Musical Arts in Contemporary Music Performance by Jonathan David Hepfer Committee in charge: Professor Steven Schick, Chair Professor Anthony Burr Professor William Arctander O’Brien Professor Jann Pasler Professor Kim Rubinstein 2016 © Jonathan David Hepfer, 2016 All rights reserved. This Dissertation of Jonathan David Hepfer is approved, and it is acceptable in quality and form for publication on microfilm and electronically: ________________________________________________________________ ________________________________________________________________ ________________________________________________________________ ________________________________________________________________ ________________________________________________________________ Chair University of California, San Diego 2016 iii DEDICATION TO: Will and Cindy for three decades of selflessness, and for saying “yes” at some crucial moments when I was really expecting to hear “no.” ! My grandfather for showing me the -

Audio Mastering for Stereo & Surround

AUDIO MASTERING FOR STEREO & SURROUND 740 BROADWAY SUITE 605 NEW YORK NY 10003 www.thelodge.com t212.353.3895 f212.353.2575 EMILY LAZAR, CHIEF MASTERING ENGINEER EMILY LAZAR CHIEF MASTERING ENGINEER Emily Lazar, Grammy-nominated Chief Mastering Engineer at The Lodge, recognizes the integral role mastering plays in the creative musical process. Combining a decisive old-school style and sensibility with an intuitive and youthful knowledge of music and technology, Emily and her team capture the magic that can only be created in the right studio by the right people. Founded by Emily in 1997, The Lodge is located in the heart of New York City’s Greenwich Village. Equipped with state-of-the art mastering, DVD authoring, surround sound, and specialized recording studios, The Lodge utilizes cutting-edge technologies and attracts both the industry’s most renowned artists and prominent newcomers. From its unique collection of outboard equipment to its sophisticated high-density digital audio workstations, The Lodge is furnished with specially handpicked pieces that lure both analog aficionados and digital audio- philes alike. Moreover, The Lodge is one of the few studios in the New York Metropolitan area with an in-house Ampex ATR-102 one-inch two-track tape machine for master playback, transfer and archival purposes. As Chief Mastering Engineer, Emily’s passion for integrating music with technology has been the driving force behind her success, enabling her to create some of the most distinctive sounding albums released in recent years. Her particular attention to detail and demand for artistic integrity is evident through her extensive body of work that spans genres and musical styles, and has made her a trailblazer in an industry notably lack- ing female representation. -

Sage Birchwater, out of Here” at the End of Our Artist of the the Day

ISSUE 5.1 | JANUARY 2014 | FREE Sage the Birchwater Featured Artist Book issue Pages 4 & 5 PAGE 2 | THE STEW Magazine | January 2014 hear | PAGE 1 January 2014 | THE STEW Magazine The Stew Magazine celebrates the written word FREE ISSUE 5.1 | JANUARY 2014 | So this is the ‘Book’ issue, the first issue of the Ne w Year. Some of our writers wanted to do the year in retrospect. I on the other hand want to talk about the history of the book and how we also use the word ‘book’ in many aspects of our life. I know in the course of On the a day in our businesses we use the word book many times. I will book the client an appointment, we will Cover: book the tuxedo for the grad or wedding, Christa will go to her computer and do our books or book- keeping and our 19-year- old employee will “book it Sage Birchwater, out of here” at the end of our artist of the the day. There are people who month, has been know you like a book. The Police might throw incredibly prolific the book at you. An event in the last few years, might be one for the books. You can make a bet cally is what we have today. started to write on lighter from the skins of animals. googled how many books as both a writer and by seeing a bookie, buy Since the dawn of hu- items, engraving on stone If your ancestors were there were in an average raffle tickets in a book and mankind we have wanted tablets and scratching into indigenous to North or library. -

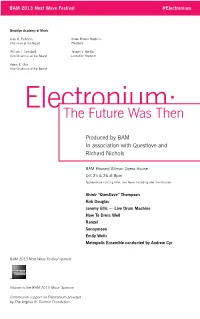

Electronium:The Future Was Then

BAM 2013 Next Wave Festival #Electronium Brooklyn Academy of Music Alan H. Fishman, Karen Brooks Hopkins, Chairman of the Board President William I. Campbell, Joseph V. Melillo, Vice Chairman of the Board Executive Producer Adam E. Max, Vice Chairman of the Board Electronium:The Future Was Then Produced by BAM In association with Questlove and Richard Nichols BAM Howard Gilman Opera House Oct 25 & 26 at 8pm Approximate running time: two hours including one intermission Ahmir “Questlove” Thompson Kirk Douglas Jeremy Ellis — Live Drum Machine How To Dress Well Rahzel Sonnymoon Emily Wells Metropolis Ensemble conducted by Andrew Cyr BAM 2013 Next Wave Festival sponsor Viacom is the BAM 2013 Music Sponsor Commission support for Electronium provided by The Virginia B. Toulmin Foundation Electronium Metropolis Ensemble conducted by Andrew Cyr: Kristin Lee, violin (concertmaster) Francisco Fullana, violin Karen Kim, viola Hiro Matsuo, cello Mellissa Hughes, soprano Virginia Warnken, alto Geoffrey Silver, tenor Jonathan Woody, bass-baritone ADDITIONAL PRODUCTION CREDITS Arrangements by Daniel Felsenfeld, DD Jackson, Patrick McMinn and Anthony Tid Lighting design by Albin Sardzinski Sound engineering by John Smeltz Stage design by Alex Delaunay Stage manager Cheng-Yu Wei Electronium references the first electronic synthesizer created exclusively for the composition and performance of music. Initially created for Motown by composer-technologist Raymond Scott, the electronium was designed but never released for distribution; the one remaining machine is undergoing restoration. Complemented by interactive lighting and aural mash-ups, the music of Electronium: The Future Was Then honors the legacy of the electronium in a production that celebrates both digital and live music interplay. -

Marian's Song Premiered by Houston Grand Opera 8:00 P.M

HGOCO PRESENTS A Chamber Opera Commissioned by Houston Grand Opera Marian's Song Premiered by Houston Grand Opera 8:00 P.M. MAY 14 AND 15, 2021 Damien Sneed | Deborah D.E.E.P Mouton MILLER OUTDOOR THEATRE “Bringing Anderson’s story to the forefront of our minds was necessary for me. To see a singer of such grace and humility navigate the harsh world around her, gives hope, for our generation, that we too can be unstoppable and make change.” —Librettist Deborah D.E.E.P. Mouton, in the Houston Chronicle Background The Story Marian’s Song is a chamber opera by composer Damien Sneed and Marian’s Song takes place both in the present day and in the past, librettist Deborah D.E.E.P. Mouton, based on the life of celebrated during Anderson’s lifetime. When current-day Howard University contralto Marian Anderson (1897–1993), who broke racial bound- student Nevaeh, who admires the singer thanks to stories shared by aries throughout her career. her grandmother, learns the church where Anderson sang as a child is slated for demolition, she travels to Philadelphia to try to save it. It was in 1939 that Anderson stood on the steps of the Lincoln Nevaeh’s journey is woven together with Anderson’s life story—her Memorial in Washington, D.C. and gave a legendary performance of disappointments, her triumphs, and along the way, the works she “America” to a crowd 75,000 strong. The historic moment took place sang so transcendently, including spirituals and classical pieces. after Anderson was denied the chance to perform at Constitution Hall by the Daughters of the American Revolution. -

Marian's Song a Chamber Opera Music by Damien Sneed Libretto by Deborah D.E.E.P Mouton Commissioned by Houston Grand Opera Premiered by Houston Grand Opera

HGOCO PRESENTS Marian's Song A Chamber Opera Music by Damien Sneed Libretto by Deborah D.E.E.P Mouton Commissioned by Houston Grand Opera Premiered by Houston Grand Opera 7:30 p.m. April 30, 2021 Available on demand through May 30, 2021 Marian's Song “Bringing Anderson’s story to the forefront of our minds was necessary for me. To see a singer of such grace and humility navigate the harsh world around her, gives hope, for our generation, that we too can be unstoppable and make change.” —Librettist Deborah D.E.E.P. Mouton, in the Houston Chronicle Background The Story Marian’s Song is a chamber opera by composer Damien Sneed and Marian’s Song takes place both in the present day and in the past, librettist Deborah D.E.E.P. Mouton, based on the life of celebrated during Anderson’s lifetime. When current-day Howard University contralto Marian Anderson (1897–1993), who broke racial bound- student Nevaeh, who admires the singer thanks to stories shared by aries throughout her career. her grandmother, learns the church where Anderson sang as a child is slated for demolition, she travels to Philadelphia to try to save it. It was in 1939 that Anderson stood on the steps of the Lincoln Nevaeh’s journey is woven together with Anderson’s life story—her Memorial in Washington, D.C. and gave a legendary performance of disappointments, her triumphs, and along the way, the works she “America” to a crowd 75,000 strong. The historic moment took place sang so transcendently, including spirituals and classical pieces. -

Words & Buried Meaning

CREATIVE ASSOCIATE SERIES Friday, Words & December 4, Buried Meaning 1pm ET Creative Associate Nico Muhly in Join us on Zoom Conversation With Iestyn Davies (Passcode: 988570) Moderated by Creative Associate Nadia Sirota Photo: Edward Nelson The Juilliard School presents Words & Buried Meaning Creative Associate Nico Muhly in Conversation With Iestyn Davies Moderated by Creative Associate Nadia Sirota This discussion between Creative Associate Nico Muhly (MM ’04, composition) and countertenor Iestyn Davies will explore their years-long collaborations, including a chamber work dealing with archaeology and the beauty of the lost past (Old Bones); a monodrama about Alan Turing (Sentences); arrangements of folk music and John Dowland; and, most recently, a song created and recorded entirely during the COVID-19 lockdowns. The conversation will be moderated by Creative Associate Nadia Sirota (BM ’04, MM ’06, viola). The program may include excerpts from the following works: Sentences: Part III Iestyn Davies, Countertenor Britten Sinfonia Nico Muhly, Composer The Bitter Withy (Traditional, arr. Muhly) Iestyn Davies, Countertenor Britten Sinfonia New-Made Tongue Iestyn Davies, Countertenor Academy of St. Martin in the Fields Oliver Zeffman, Conductor Nico Muhly, Composer Old Bones Iestyn Davies, Countertenor Thomas Dunford, Theorbo Nico Muhly, Composer Time Stands Still (Dowland, arr. Muhly) Iestyn Davies, Countertenor Aurora Orchestra Nicholas Collon, Conductor 1 Juilliard’s Creative Enterprise programming, including the Creative Associates program, is generously sponsored by Jody and John Arnhold. Special thanks to Kevin Anthenill, Olivia Fitzsimons, James Lemkin, Fritz Myers, Sue Spence, and the many members of the Juilliard community who helped bring this program to life. 2 Panelists Nico Muhly Creative Associate Nico Muhly (MM ’04, composition) is an American composer and sought-after collaborator whose influences range from American minimalism to the Anglican choral tradition. -

STG Presents an Average of 600 Events Annually at the Paramount, the Moore, and the Neptune Theatres As Well As at Other Venues Throughout the Region

STG presents an average of 600 events annually at The Paramount, The Moore, and The Neptune Theatres as well as at other venues throughout the region. Broadway productions, concerts, comedy, lectures, education & community programs, film, and other enrichment programs can be found in our venues. Please see below for a chronological list of performances. ● THING - CANCELLED - - Fort Worden ● AIN'T TOO PROUD - CANCELLED - - The Paramount Theatre ● Black Pumas - POSTPONED - - The Paramount Theatre ● John Hiatt & The Jerry Douglas Band - POSTPONED - - The Moore Theatre ● DANCE This! Virtual Performance - August 13, 2021 - Online ● Pop-Up Mini Golf at the Paramount Theatre - August 12 - 15 - The Paramount Theatre ● Tiny Meat Gang - CANCELLED - - The Moore Theatre ● Tune-Yards - August 7, 2021 - The Neptune Theatre ● Palaye Royale - POSTPONED - - The Neptune Theatre ● Joe Russo's Almost Dead - CANCELLED - - The Paramount Theatre ● The Decemberists - CANCELLED - - The Paramount Theatre ● Up Next: Summer 2021 Series - July 24 - August 28, 2021 - Starbucks SODO Reserve ● The Masked Singer Live - CANCELLED - - The Paramount Theatre ● Jason Isbell and The 400 Unit - POSTPONED - - The Paramount Theatre ● IRC Residency - July 12, 2021 - Cascade View Elementary ● Girls Gotta Eat - POSTPONED - - The Moore Theatre ● More Music Songwriters Sessions 2021 - July 7, 2021 - Online ● STG Virtual AileyCamp 2021 - July 7 - August 4, 2021 - Online ● Pop-Up Donor Center with Bloodworks Northwest at The Paramount - July 6 - 9, 2021 - The Paramount Theatre ● Brit -

Kinan Azmeh + Aizuri Quartet “Music & Migration” • May 31, 2018 • 7:30 P.M

LiveConnections Presents Kinan Azmeh + Aizuri Quartet “Music & Migration” • May 31, 2018 • 7:30 p.m. World Cafe Live, Philadelphia Armenian Folk Songs Komitas Vartabed (1869-1935) arr. Sergei Aslamazian I. Yergink Ampel A (It’s Cloudy) II. Haprpan (Festive Song) III. Shoushigi (For Shoushig) IV. Echmiadzni Bar (Dance from Echmiadzin) V. Kaqavik (The Partridge) The Fence, the Rooftop and the Distant Sea (2018) Kinan Azmeh (b. 1976) World premiere of version for clarinet and string quartet, commissioned by the Aizuri Quartet I. Prologue II. Ammonite III. Monologue IV. Dance V. Epilogue RIPEFG (2016) Yevgeniy Sharlat (b. 1977) Commissioned for the Aizuri Quartet by the Curtis Institute of Music I. Vivo INTERMISSION These Memories May Be True (2012) Lembit Beecher (b. 1980) III. Estonian Grandmother Superhero IV. Variations on a Somewhat Old Folk Song Suite of Micro-commissions for String Quartet and Clarinet (2018) World premiere, commissioned by the Aizuri Quartet I. Irresolvable Fragment Can Bilir (b. 1987) II. Diente de León Pauchi Sasaki (b. 1981) III. Between Air Wang Lu (b. 1982) IV. Lullaby for the Transient Michi Wiancko (b. 1976) Kinan Azmeh, clarinet Aizuri Quartet Ariana Kim & Miho Saegusa, violins; Ayane Kozasa, viola; Karen Ouzounian, cello inspiring learning & building community through collaborative music-making liveconnections.org WELCOME FROM LIVECONNECTIONS “MUSIC & MIGRATION” PROGRAM NOTES —The Aizuri Quartet Earlier this month, LiveConnections turned 10 years old. We’ve been spending a lot of time looking back at a About his piece, Kinan Azmeh writes, “A fence, a rooftop and remarkable first decade, and also looking ahead to envision the distant sea were all present there facing my desk while I what comes next. -

Deutsche Nationalbibliografie 2013 T 07

Deutsche Nationalbibliografie Reihe T Musiktonträgerverzeichnis Monatliches Verzeichnis Jahrgang: 2013 T 07 Stand: 17. Juli 2013 Deutsche Nationalbibliothek (Leipzig, Frankfurt am Main) 2013 ISSN 1613-8945 urn:nbn:de:101-ReiheT07_2013-6 2 Hinweise Die Deutsche Nationalbibliografie erfasst eingesandte Pflichtexemplare in Deutschland veröffentlichter Medienwerke, aber auch im Ausland veröffentlichte deutschsprachige Medienwerke, Übersetzungen deutschsprachiger Medienwerke in andere Sprachen und fremdsprachige Medienwerke über Deutschland im Original. Grundlage für die Anzeige ist das Gesetz über die Deutsche Nationalbibliothek (DNBG) vom 22. Juni 2006 (BGBl. I, S. 1338). Monografien und Periodika (Zeitschriften, zeitschriftenartige Reihen und Loseblattausgaben) werden in ihren unterschiedlichen Erscheinungsformen (z.B. Papierausgabe, Mikroform, Diaserie, AV-Medium, elektronische Offline-Publikationen, Arbeitstransparentsammlung oder Tonträger) angezeigt. Alle verzeichneten Titel enthalten einen Link zur Anzeige im Portalkatalog der Deutschen Nationalbibliothek und alle vorhandenen URLs z.B. von Inhaltsverzeichnissen sind als Link hinterlegt. Die Titelanzeigen der Musiktonträger in Reihe T sind, wie Katalogisierung, Regeln für Musikalien und Musikton-trä- auf der Sachgruppenübersicht angegeben, entsprechend ger (RAK-Musik)“ unter Einbeziehung der „International der Dewey-Dezimalklassifikation (DDC) gegliedert, wo- Standard Bibliographic Description for Printed Music – bei tiefere Ebenen mit bis zu sechs Stellen berücksichtigt ISBD (PM)“ zugrunde. -

FY14 Annual Report View Report

Annual Report 2013–14 1 2 Introduction 4 Metropolitan Opera Board of Directors 5 2013–14 Season Repertory & Events 12 2013–14 Artist Roster 14 The Financial Results 47 Patrons 1 Introduction The Metropolitan Opera’s 2013–14 season featured an extraordinary number of artistic highlights, while the company continued to address the significant financial challenges of grand opera. The Met presented six new productions during the 2013–14 season, including the Met premiere of Nico Muhly’s Two Boys, the first new opera developed through the company’s co-commissioning program with Lincoln Center Theater. The season also saw the first Met performances in nearly 100 years of Borodin’s Prince Igor. Along with four revivals, all six new productions were presented in movie theaters around the world as part of the Met’s Live in HD series, which earned $26.2 million. Combined earned revenue for the Met (Live in HD and box office) totaled $117 million. While enjoying great artistic successes, the company faced challenging economic hurdles, ending with a deficit after five years of break-even or close to break-even results. However, contract negotiations with the Met’s unions, still in process at the end of the fiscal year, resulted in cost reductions to help ensure a more sustainable financial model for the future. At the start of the 2013–14 season, Music Director James Levine made a highly anticipated—and enormously successful—return to the Met after two years away due to injury. His return on the second night of the season to conduct Mozart’s Così fan tutte was rapturously received, as were his performances leading Robert Carsen’s new production of Verdi’s Falstaff.