Iowa's Prohibition Plague

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Gone Rogue: Time to Reform the Presidential Primary Debates

Joan Shorenstein Center on the Press, Politics and Public Policy Discussion Paper Series #D-67, January 2012 Gone Rogue: Time to Reform the Presidential Primary Debates by Mark McKinnon Shorenstein Center Reidy Fellow, Fall 2011 Political Communications Strategist Vice Chairman Hill+Knowlton Strategies Research Assistant: Sacha Feinman © 2012 President and Fellows of Harvard College. All rights reserved. How would the course of history been altered had P.T. Barnum moderated the famed Lincoln-Douglas debates in 1858? Today’s ultimate showman and on-again, off-again presidential candidate Donald Trump invited the Republican presidential primary contenders to a debate he planned to moderate and broadcast over the Christmas holidays. One of a record 30 such debates and forums held or scheduled between May 2011 and March 2012, this, more than any of the previous debates, had the potential to be an embarrassing debacle. Trump “could do a lot of damage to somebody,” said Karl Rove, the architect of President George W. Bush’s 2000 and 2004 campaigns, in an interview with Greta Van Susteren of Fox News. “And I suspect it’s not going to be to the candidate that he’s leaning towards. This is a man who says himself that he is going to run— potentially run—for the president of the United States starting next May. Why do we have that person moderating a debate?” 1 Sen. John McCain of Arizona, the 2008 Republican nominee for president, also reacted: “I guarantee you, there are too many debates and we have lost the focus on what the candidates’ vision for America is.. -

Party and Non-Party Political Committees Vol. II State and Local Party Detailed Tables

FEC REPORTS ON FINANCIAL ACTIVITY 1989 - 1990 FINAL REPORT .. PARTY AND NON-PARTY POLITICAL COKMITTEES VOL.II STATE AND LOCAL PARTY DETAILED TABLES FEDERAL ELECTION COMMISSION 999 E Street, N.W. Washington, D.C. 20463 OCTOBER 1991 I I I I I I I I FEDERAL ELECTION COMMISSION Commissioners John w. McGarry, Chairman Joan D. Aikens, Vice Chairman Lee Ann Elliott, Thomas J. Josefiak Danny L. McDonald Scott E. Thomas Donnald K. Anderson, Ex Officio Clerk of the u.s. House of Representatives Walter J. Stewart Secretary of the Senate John C. Surina, Staff Director Lawrence M. Noble, General Counsel Comments and inquiries about format should be addressed to the Reports Coordinator, Data System Development Division, who coordinated the production of this REPORT. Copies of 1989-1990 FINAL REPORT, PARTY AND NON-PARTY POLITICAL COMMITTEES, may be obtained b writing to the Public Records Office, Federal Election Commission, 999 E Street, N.W. Washington, D.C. 20463. Prices are: VOL. I - $10.00, VOL. II - $10.00, VOL. III - $10.00, VOL IV - $10.00. Checks should be made payable to the Federal Election Commission. TABLE OF CONTENTS I. DESCRIPTION OF REPORT iv II. SUMMARY OF TABLES vi III. EXPLANATION OF COLUMNS viii IV. TABLES: SELECTED FINANCIAL ACTIVITY AND ASSISTANCE TO CANDIDATES, DEMOCRATIC AND REPUBLICAN STATE AND LOCAL POLITICAL COMMITTEES A. SELECTED FINANCIAL ACTIVITY OF DEMOCRATIC STATE AND LOCAL POLITICAL COMMITTEES AND THEIR ASSISTANCE TO CANDIDATES BY OFFICE AND PARTY Alabama 1 Missouri 37 Colorado 7 New York 43 Idaho 13 Ohio 49 Kansas 19 -

Justice in the Justice Trial at Nuremberg Stephen J

University of Baltimore Law Review Volume 46 | Issue 3 Article 4 5-2017 A Court Pure and Unsullied: Justice in the Justice Trial at Nuremberg Stephen J. Sfekas Circuit Court for Baltimore City, Maryland Follow this and additional works at: http://scholarworks.law.ubalt.edu/ublr Part of the Fourteenth Amendment Commons, International Law Commons, and the Legal History Commons Recommended Citation Sfekas, Stephen J. (2017) "A Court Pure and Unsullied: Justice in the Justice Trial at Nuremberg," University of Baltimore Law Review: Vol. 46 : Iss. 3 , Article 4. Available at: http://scholarworks.law.ubalt.edu/ublr/vol46/iss3/4 This Peer Reviewed Articles is brought to you for free and open access by ScholarWorks@University of Baltimore School of Law. It has been accepted for inclusion in University of Baltimore Law Review by an authorized editor of ScholarWorks@University of Baltimore School of Law. For more information, please contact [email protected]. A COURT PURE AND UNSULLIED: JUSTICE IN THE JUSTICE TRIAL AT NUREMBERG* Hon. Stephen J. Sfekas** Therefore, O Citizens, I bid ye bow In awe to this command, Let no man live Uncurbed by law nor curbed by tyranny . Thus I ordain it now, a [] court Pure and unsullied . .1 I. INTRODUCTION In the immediate aftermath of World War II, the common understanding was that the Nazi regime had been maintained by a combination of instruments of terror, such as the Gestapo, the SS, and concentration camps, combined with a sophisticated propaganda campaign.2 Modern historiography, however, has revealed the -

Republican Loyalist: James F. Wilson and Party Politics, 1855-1895

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Iowa Research Online The Annals of Iowa Volume 52 Number 2 (Spring 1993) pps. 123-149 Republican Loyalist: James F. Wilson and Party Politics, 1855-1895 Leonard Schlup ISSN 0003-4827 Copyright © 1993 State Historical Society of Iowa. This article is posted here for personal use, not for redistribution. Recommended Citation Schlup, Leonard. "Republican Loyalist: James F. Wilson and Party Politics, 1855-1895." The Annals of Iowa 52 (1993), 123-149. Available at: https://doi.org/10.17077/0003-4827.9720 Hosted by Iowa Research Online Republican Loyalist: James F. Wilson and Party Politics, 1855-1895 LEONARD SCHLUP ONE OF THE FOUNDING FATHERS of Iowa Republican- ism, James F. Wilson (1828-1895) represented his party and his state in the United States House of Representatives from 1861 to 1869 and the United States Senate from 1882 to 1895. A number of his contemporaries have been the subjects of excellent studies, and various memoirs and autobiogra- phies have helped to illuminate certain personalities and events of the period. ^ Yet Wilson's political career has re- ceived comparatively little notice. In the accounts of his con- temporaries, he appears in scattered references to isolated fragments of his life, while the general surveys of Iowa history either ignore him or mention him only briefly.^ He deserves better treatment. This essay sketches the outlines of Wilson's political career and suggests his role as conciliator in Iowa's Republican party politics. I hope the essay will help readers see Wilson's political career in a broader perspective 1. -

CONGRESSIONAL RECORD—SENATE June 15, 2005 by Mr

June 15, 2005 CONGRESSIONAL RECORD—SENATE 12755 EC–2638. A communication from the Gen- EC–2648. A communication from the Assist- tities’’ (FRL No. 7924–9) received on June 14, eral Counsel, Federal Emergency Manage- ant Administrator, National Marine Fish- 2005; to the Committee on Environment and ment Agency, Department of Homeland Se- eries Service, Department of Commerce, Public Works. curity, transmitting, pursuant to law, the re- transmitting, pursuant to law, the report of EC–2657. A communication from the Prin- port of a rule entitled ‘‘Final Flood Ele- a rule entitled ‘‘Atlantic Highly Migratory cipal Deputy Associate Administrator, Office vation Determinations (70 FR 29639)’’ (44 CFR Species; Atlantic Shark Quotas and Season of Policy, Economics, and Innovation, Envi- 67) received on June 14, 2005; to the Com- Lengths’’ ((RIN0648–AT07) (I.D. No. 020205F)) ronmental Protection Agency, transmitting, mittee on Banking, Housing, and Urban Af- received on June 14, 2005; to the Committee pursuant to law, the report of a rule entitled fairs. on Commerce, Science, and Transportation. ‘‘Hazardous Waste Management System; EC–2639. A communication from the Gen- EC–2649. A communication from the Acting Modification of the Hazardous Waste Mani- eral Counsel, Federal Emergency Manage- White House Liaison, Technology Adminis- fest System; Correction’’ (FRL No. 7925–1) re- ment Agency, Department of Homeland Se- tration, Department of Commerce, transmit- ceived on June 14, 2005; to the Committee on curity, transmitting, pursuant to law, the re- ting, pursuant to law, the report of a va- Environment and Public Works. port of a rule entitled ‘‘Final Flood Ele- cancy in the position of Under Secretary for EC–2658. -

MU»# JL*±=S=— WOCT20 AM 10:38 Office of General Counsel Federal Election Commission OFFICE of GENERAL 999 E Street, N.W

FEDERAL ELECTION COMMISSION October 19.2009 ~ / 4f/J MU»#_JL*±=S=— WOCT20 AM 10:38 Office of General Counsel Federal Election Commission OFFICE OF GENERAL 999 E Street, N.W. COUNSEL Washington, D.C. 20463 RE: Steve Scheffler, President of the lowi Christian Alliance Morris Kurd, Chairman of the Board and Tmuurer of the Iowa Christian Alliance Ic^ChristianAHiaiice-939OfflcePa2kIU)e4Sunell5;WeslI^MoiiiestU 50265 West Hill United Methodist Chwch-540 S.Uebrick Street; ftirh^ 52601 LSI MorrbHiBd-RM of We* HU1 United M Ni ^4 To Whom It May Concern: «r l£ The Iowa Christian Alliance (ICA) is a tax exempt iMiiproftaiidfliiaDcialccfitributionstothelCAare M NOT tax deductible. ^r <qr It is my understanding that Steve Scneffler.Preiidertef die loin Oriita n Chairman of the Boeri aid lYeuur^ Q intended for the ICA through tne West Hffl United Methodist Church fa Buriingto^ They do this so ^ that donors can make a TAX DETXKHTBI£coi»TbutiontotheICA. Morris Hurd is also the pastor of West Hill United Methodist Church. ftvnrybelktfflMtttlieieiliim^ finance laws, the tax exempt iliiiia of the ICA, and the tax exempt ****w lor ne church. According to a phone call I received from Ted Spocer (attoniey.polhlcal activist and friend of Steve Schcffler) on Febnwy II, 2009, Sieve SdieftoadidBifh^^ If a donor that Mr. Scheffler knows and trusts wants to mate a TAX DEDUCTIBLE ccotribirtm to the ICA, Mr. Scheffler asks the donor to write • check for nel(^ and seiidh to Pastor MctrisHuid at the West HiU Untod Methodist Church. Once n^ donor wrh^ a check fiv the 1C A and sends ft to the church, Pastor Hurd sends • document from the church thanting the donor for their ^d^^ Hill United Methodist Church. -

Black Hills Chapter GRHS News

Black Hills Chapter GRHS News April 2017 22nd Year Anniversary of this Newsletter! Volume 22, Issue 2 15th Annual German Dinner—It Takes a Village It really does take a village! We must: Reserve venue at Blessed Sacrament Parish Center a year in advance. Begin planning in November for the Dinner on March 5, 2017. Obtain beer license. Print tickets and pass them out in December. Sell 700 tickets. Purchase disposable dinner and kuchen plates, plastic tableware, coffee and water cups, and nap- kins. Wrap settings of tableware in napkins 800 times. Estimate food needs and place orders. Thursday, three days before the Dinner: Set out for Eureka, SD to pick up 630 pounds of Kauk’s sausage and to Ashley, ND to get 215 Grandma’s kuchen. Power wash all containers. Wash, steam and boil 300 pounds of potatoes. Peel and slice 168 pounds of on- ions to be fried. Chop up the uncut onion ends to be used in sauer- kraut. Chop three commercial bags of parsley and three more of green onions, both for German potato salad. Fry up 4 pounds freshly ground bacon bits for potato salad. Total, 16 volunteers. Friday: Measure out containers of dressing to be used for 24 ten-pound batches of potato salad. 19 volunteers peel all those potatoes in one hour. 5 more then cut out any remaining eyes and blemishes. 4 more slice the potatoes and mix in the dressing. Grate two galloons of potatoes for sauerkraut. Return from across the state with frozen sausage and kuchen. Total, 27 volunteers. -

Republican Party of Iowa 621 East 9Th Street Des Moines, IA 50309 ! !

Republican Party of Iowa 621 East 9th Street Des Moines, IA 50309 ! ! TO: Interested Parties FROM: Jeff Kaufmann Chairman, Republican Party of Iowa DATE: May 27, 2015 SUBJECT: Participation in 2015 Straw Poll Preliminary Meetings Several individuals who are considering running for the Republican nomination for President in 2016, but who have not yet declared their candidacies, have questioned their ability to participate in the preliminary planning meetings for the 2015 Iowa Straw Poll (the “Straw Poll”) while they “test the waters” for a potential candidacy. Such individuals have expressed concerns that their participation in these preliminary meetings will trigger “candidate” status under federal election laws and require them to register as candidates with the Federal Election Commission (the “Commission”). In short, participation in the preliminary planning meetings for the Straw Poll would not cause these individuals to trigger candidate status. Iowa Straw Poll Preliminary Meetings In the lead up to the August 8, 2015 Straw Poll, the Republican Party of Iowa (“RPI”) will hold a number of preliminary meetings to address certain logistical issues for participants, potential participants, consultants and vendors. At these preliminary meetings, RPI will distribute draft rules for the Straw Poll, circulate a draft map and layout of the Straw Poll, provide an overview of the event’s activities, and address logistics about speaking order and ticket sales. Participation in the Straw Poll and any preliminary meetings leading up to the Straw Poll are by invitation only. RPI has invited declared candidates for President, as well as individuals who are not candidates but are considering running for President in 2016. -

Bryan, Cleveland, and the Disrupted Democracy Scroll Down for Complete Article

Nebraska History posts materials online for your personal use. Please remember that the contents of Nebraska History are copyrighted by the Nebraska State Historical Society (except for materials credited to other institutions). The NSHS retains its copyrights even to materials it posts on the web. For permission to re-use materials or for photo ordering information, please see: http://www.nebraskahistory.org/magazine/permission.htm Nebraska State Historical Society members receive four issues of Nebraska History and four issues of Nebraska History News annually. For membership information, see: http://nebraskahistory.org/admin/members/index.htm Article Title: Bryan, Cleveland, and the Disrupted Democracy Full Citation: Paolo E Coletta, “Bryan, Cleveland, and the Disrupted Democracy,” Nebraska History 41 (1960): 1- 27 URL of article: http://www.nebraskahistory.org/publish/publicat/history/full-text/NH1960DisruptedDemocracy.pdf Date: 10/27/2016 Article Summary: Chaos prevailed in the Democratic Party in the 1890s when Bryan’s revolutionary leadership threatened Cleveland’s long-accepted ways. Even Bryan’s opponents recognized his courage when he fought Cleveland’s gold policies and his support for the privileged. Scroll down for complete article. Cataloging Information: Names: William Jennings Bryan, Grover Cleveland, George L Miller, Charles F Crisp, William M Springer, J P Morgan, J Sterling Morton, William Vincent Allen, Silas A Holcomb, James B Weaver, Euclid Martin, Richard Parks (“Silver Dick”) Bland Keywords: William Jennings Bryan, Grover Cleveland, Populists, fusion, free silver, Sherman Silver Purchase Act (1890), tariff reform, Ways and Means committee, Fifty-Third Congress, bimetallism, Bourbon Democrats, goldbugs, Credentials Committee, bolters BRYAN, CLEVELAND, AND THE DISRUPTED DEMOCRACY, 1890-1896 BY PAOLO E. -

William Jennings Bryan and the Nebraska Senatorial Election of 1893

William Jennings Bryan and the Nebraska Senatorial Election of 1893 (Article begins on page 2 below.) This article is copyrighted by History Nebraska (formerly the Nebraska State Historical Society). You may download it for your personal use. For permission to re-use materials, or for photo ordering information, see: https://history.nebraska.gov/publications/re-use-nshs-materials Learn more about Nebraska History (and search articles) here: https://history.nebraska.gov/publications/nebraska-history-magazine History Nebraska members receive four issues of Nebraska History annually: https://history.nebraska.gov/get-involved/membership Full Citation: Paolo E Coletta, “William Jennings Bryan and the Nebraska Senatorial Election of 1893,” Nebraska History 31 (1950): 183-203 Article Summary: Bryan lost more than he gained in his first campaign for the Senate. He needed to master the Nebraska political situation, but he chose instead to fight for a national issue, free silver. Cataloging Information: Names: William Jennings Bryan, Grover Cleveland, Richard (“Silver Dick”) Bland, Allen W Field, William McKeighan, J Sterling Morton, James E Boyd, Tobe Castor, Omar M Kem, John M Thurston, A S Paddock, Thomas Stinson Allen, William V Allen Keywords: William Jennings Bryan, Grover Cleveland, William Vincent Allen, free silver, tariff reform, income tax, Populists, Democrats, patronage, Photographs / Images: William Vincent Allen, John M Thurston, A S Paddock, J Sterling Morton, James E Boyd WILLIAM JENNINGS BRYAN AND THE NEBRASKA SENATORIAL ELECTION OF 1893 BY PAOLO E. COLETTA HE Nebraska senatorial election of 1893 proved a side show for William Jennings Bryan in which he lost T more than he gained, but it is evident that he learned some lessons from his experience and that the election was considered important enough in national affairs to justify the intervention of the Democratic National Committee in a state contest. -

Success. Cause of the Him to Use Itfor His Personal Choice of the Real Democrats Offlorida

THE SAN FRANCISCO CALL, SATURDAY, JULY 11, 1896. 3 SOME FAMOUS SPEECHES BY ORATORS AT NATIONAL CONVENTIONS. By reason of the very general belief that the nomination of William J. Bryan for the constitution by proclaiming that the militaryrule shall ever be subservient to the civil The el ection power. The before us will be the Ansterlitz of American politics. Itwilldecide whether States by the Democratic National Convention at Chicago was plighted word of a soldier was proved by the acts of a statesman. Inominate one foryears tocome the country willbe Republican or Cossack. ••"••« defeated President of the United name will factions, will be Never in war subject whose suppress all alike acceptable to the North and to the or inpeace, his name is the most illustrious borne by any livingman; his Jargelv effected by bis famous speech for silver, the of National Convention South— aname name, if services attest his that willthrill the Republic, a nominated, of a man that will crush, greatness, and the country knows them by heart. His fame was born not alone of things writ- oratory on new Interest. Mr. Bryan is not the first orator who has by well- the last embers of sectional strife, and whose name willbe dawning day take? hailed as the of the of ten and said, but of the arduous groatness of things done, and dangers and emergencies will enthusiasm delegates. are submitted perpetual brotherhood. With him we can flingaway our shields and wage an aggressive war. in vain in the rounded periods awakened the of Below extracts appeal search future, as they have searched in vain in the past, for any other on whom orations, We can to the supreme tribunal of the American people against the corruption of the the Nation leaus with • * • from various convention including some of the more striking passages of Mr. -

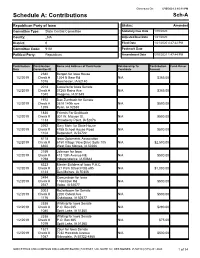

Schedule A: Contributions Sch-A

Generated On: 5/10/2021 2:15:11 PM Schedule A: Contributions Sch-A Republican Party of Iowa Status: Amended Committee Type: State Central Committee Statutory Due Date 1/19/2020 County: _NA Adjusted Due Date 1/21/2020 District: 0 Filed Date 1/21/2020 4:27:22 PM Committee Code: 9161 Postmark Date Political Party: Republican Amendment Date 5/10/2021 1:47:44 PM Contribution Contribution Name and Address of Contributor Relationship To Contribution Fund-Raiser Date Committee ID Candidate Amount 2382 Bergan for Iowa House 1/2/2019 Check # 1204 N Bear Rd N/A $365.00 1078 Dorchester, IA 52140 2014 Costello for Iowa Senate 1/2/2019 Check # 37265 Rains Ave N/A $365.00 1040 Imogene, IA 51645 1972 Dan Zumbach for Senate 1/2/2019 Check # 2618 140th ave N/A $500.00 1255 Ryan, IA 52330 1838 Friends For Breitbach 1/2/2019 Check # 301 W. Mission St. N/A $500.00 1133 Strawberry Point, IA 52076 2252 Gary Mohr for State House 1/2/2019 Check # 4755 School House Road N/A $500.00 1104 Bettendorf, IA 52722 6118 Iowa Optometric Association 1/2/2019 Check # 6150 Village View Drive Suite 105 N/A $2,500.00 6360 West Des Moines, IA 50266 2159 Johnson for Iowa 1/2/2019 Check # 413 13th Avenue NE N/A $500.00 1098 Independence, IA 50644 6323 Master Builders of Iowa P.A.C. 1/2/2019 Check # 221 Park Street POB 695 N/A $1,000.00 4144 Des Moines, IA 50306 2494 Osmundson for Iowa 1/2/2019 Check # 11663 Bell Rd N/A $500.00 0547 Volga, IA 52077 2003 Rozenboom for Senate 1/2/2019 Check # 2200 Oxford Ave N/A $500.00 1176 Oskaloosa, IA 52577 2338 Whiting for Iowa Senate 1/2/2019 Check # P.O.