Is Kamala Harris Typical 2

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

“Momala” Ou L'incroyable Histoire D'une Famille Recomposée

A la une / Magazine Kamala Harris, première femme noire candidate à la vice-présidence des États-Unis “Momala” ou l’incroyable histoire d’une famille recomposée La sénatr ice Kamal a Harris. © D.R Son choix d’“invitées” au jour de sa nomination historique, pendant le centenaire du droit des votes des Américaines, l'a dit clairement : honneur aux femmes et à la famille. C’est présentée partrois femmes proches que Kamala Harris a accepté mercredi soir sa candidature historique à la vice-présidence des États-Unis, symbole de l'importance centrale de sa “famille moderne” dans la vie de celle qui aime se faire appeler “Momala” par les enfants de son mari. Première femme noire et d'origine indienne à briguer ce poste, elle deviendra la première femme vice- présidente des États-Unis si Joe Biden remporte l'élection contre Donald Trump le 3 novembre. Et dans ce pays où les conjoints et enfants occupent un rôle central dans les campagnes électorales, sa famille ne coche aucune case traditionnelle. Mais elle a cherché à présenter un front uni et aimant mercredi. Son choix d’“invitées” au jour de sa nomination historique, pendant le centenaire du droit des votes des Américaines, l'a dit clairement : honneur aux femmes et à la famille. Dans toutes ses variantes. “Kamala Harris est ma tante, ma belle-mère, ma grande sœur” : les voix se sont enchaînées dans un montage vidéo, montrant trois femmes centrales dans sa vie : sa sœur Maya Harris, ancienne de la campagne de Hillary Clinton en 2016, qui avait dirigé la candidature malheureuse de Kamala Harris à la primaire démocrate en 2019. -

23 Black Leaders Who Are Shaping History Today

23 Black Leaders Who Are Shaping History Today Published Mon, Feb 1 20219:45 AM EST Updated Wed, Feb 10 20211:08 PM EST Courtney Connley@CLASSICALYCOURT Vice President Kamala Harris, poet Amanda Gorman, Sen. Raphael Warnock, nurse Sandra Lindsay and NASA astronaut Victor Glover. Photo credit: Getty; Photo Illustration: Gene Kim for CNBC Make It Black Americans have played a crucial role in helping to advance America’s business, political and cultural landscape into what it is today. And since 1976, every U.S. president has designated the month of February as Black History Month to honor the achievements and the resilience of the Black community. While CNBC Make It recognizes that Black history is worth being celebrated year-round, we are using this February to shine a special spotlight on 23 Black leaders whose recent accomplishments and impact will inspire many generations to come. These leaders, who have made history in their respective fields, stand on the shoulders of pioneers who came before them, including Shirley Chisholm, John Lewis, Maya Angelou and Mary Ellen Pleasant. 6:57 How 7 Black leaders are shaping history today Following the lead of trailblazers throughout American history, today’s Black history-makers are shaping not only today but tomorrow. From helping to develop a Covid-19 vaccine, to breaking barriers in the White House and in the C-suite, below are 23 Black leaders who are shattering glass ceilings in their wide-ranging roles. Kamala Harris, 56, first Black, first South Asian American and first woman Vice President Vice President Kamala Harris. -

Resolution Calling on the BUSD Board and Superintendent to Consider Renaming Thousand Oaks Elementary to Kamala Harris Elementary School

Page 1 of 4 CONSENT CALENDAR December 1, 2020 To: Honorable Members of the City Council From: Vice Mayor Sophie Hahn (Author) Subject: Resolution calling on the BUSD Board and Superintendent to Consider Renaming Thousand Oaks Elementary to Kamala Harris Elementary School RECOMMENDATION Adopt a Resolution calling on the Berkeley Unified School District (BUSD) Board and Superintendent to consider initiating a process, pursuant to BUSD Board Policy and Administrative Regulation 7310, to rename Thousand Oaks Elementary School to Kamala Harris Elementary School in honor of Vice President-Elect Kamala Harris. BACKGROUND On Tuesday, November 3, 2020, Joe Biden and Kamala Harris were elected as the next President and Vice President of the United States, having received the largest number of votes in U.S. history. Vice President-Elect Harris is the first African American and Indian American woman to be elected to the Office of Vice President or President. Kamala Harris was born in 1964 to two graduate students at the University of California, Berkeley -- her mother, Shyamala Gopalan Harris, from India and father, Donald Harris, from Jamaica. As Senator Harris said in the speech accepting the Democratic Party’s nomination for Vice President, she “got a stroller’s-eye view” of the civil rights movement of the 1960s as her parents marched for justice in the streets of Berkeley. Kamala Harris grew up in West Berkeley and attended Thousand Oaks Elementary School in District 5. She was in the second class to be part of the Berkeley school integration program -- an innovative two-way busing plan designed to fully integrate Berkeley’s public schools. -

Eye on the World Aug

Eye on the World Aug. 15, 2020 This compilation of material for “Eye on the World” is presented as a service to the Churches of God. The views stated in the material are those of the writ- ers or sources quoted by the writers, and do not necessarily reflect the views of the members of the Church of God Big Sandy. The following articles were posted at churchofgodbigsandy.com for the weekend of August 15, 2020. Compiled by Dave Havir Luke 21:34-36—“But take heed to yourselves, lest your souls be weighed down with self-indulgence, and drunkenness, or the anxieties of this life, and that day come on you suddenly, like a falling trap; for it will come on all dwellers on the face of the whole earth. But beware of slumbering; and every moment pray that you may be fully strengthened to escape from all these coming evils, and to take your stand in the presence of the Son of Man” (Weymouth New Testament). ★★★★★ An article by Raoul Wootliff titled “Hailing ‘New Era With Arab World,’ Netan- yahu Says Others Will Follow UAE’s Lead” was posted at timesofisrael.com on Aug. 13, 2020. Following is the article. __________ Announcing details of the historic agreement for full diplomatic relations between Israel and the United Arab Emirates, Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu on Thursday night hailed what he called a “new era of Israeli relations with the Arab world,” and said other deals with Arab countries would follow. He also insisted that he would continue to seek to extend Israeli sovereignty to parts of the West Bank land, in coordination with the US, but acknowl- edged that his plan for unilateral annexation was being temporarily halted, in line with the joint statement issued by the US, Israel and the UAE which spec- ified that Israel would “suspend” the move. -

Berkeley City Council Agenda & Rules Committee Special Meeting

BERKELEY CITY COUNCIL AGENDA & RULES COMMITTEE SPECIAL MEETING MONDAY, NOVEMBER 16, 2020 2:30 P.M. Committee Members: Mayor Jesse Arreguin, Councilmembers Sophie Hahn and Susan Wengraf Alternate: Councilmember Ben Bartlett PUBLIC ADVISORY: THIS MEETING WILL BE CONDUCTED EXCLUSIVELY THROUGH VIDEOCONFERENCE AND TELECONFERENCE Pursuant to Section 3 of Executive Order N-29-20, issued by Governor Newsom on March 17, 2020, this meeting of the City Council Agenda & Rules Committee will be conducted exclusively through teleconference and Zoom videoconference. Please be advised that pursuant to the Executive Order, and to ensure the health and safety of the public by limiting human contact that could spread the COVID-19 virus, there will not be a physical meeting location available. To access the meeting remotely using the internet: Join from a PC, Mac, iPad, iPhone, or Android device: Use URL https://us02web.zoom.us/j/82045200899. If you do not wish for your name to appear on the screen, then use the drop down menu and click on "rename" to rename yourself to be anonymous. To request to speak, use the “raise hand” icon on the screen. To join by phone: Dial 1-669-900-9128 or 1-877-853-5257 (Toll Free) and Enter Meeting ID: 820 4520 0899. If you wish to comment during the public comment portion of the agenda, press *9 and wait to be recognized by the Chair. Written communications submitted by mail or e-mail to the Agenda & Rules Committee by 5:00 p.m. the Friday before the Committee meeting will be distributed to the members of the Committee in advance of the meeting and retained as part of the official record. -

The Lockdown to Contain the Coronavirus Outbreak Has Disrupted Supply Chains

JOURNALISM OF COURAGE SINCE 1932 The lockdown to contain the coronavirus outbreak has disrupted supply chains. One crucial chain is delivery of information and insight — news and analysis that is fair and accurate and reliably reported from across a nation in quarantine. A voice you can trust amid the clanging of alarm bells. Vajiram & Ravi and The Indian Express are proud to deliver the electronic version of this morning’s edition of The Indian Express to your Inbox. You may follow The Indian Express’s news and analysis through the day on indianexpress.com DAILY FROM: AHMEDABAD, CHANDIGARH, DELHI, JAIPUR, KOLKATA, LUCKNOW, MUMBAI, NAGPUR, PUNE, VADODARA JOURNALISM OF COURAGE SATURDAY, AUGUST 22, 2020, NEW DELHI, LATE CITY, 16 PAGES SINCE 1932 `6.00 (`8 PATNA &RAIPUR, `12 SRINAGAR) WWW.INDIANEXPRESS.COM THE EDITORIAL PAGE OFFICIAL NOTE TO MEA NAGATALKS: BRIDGINGTHE AswithPak, NARRATIVEDIVIDE BY SANJIB BARUAH PAGE 8 selectChina BUSINESSASUSUAL entitiesface BY UNNY extravisascan Official:Tie-ups of Indian universities, institutionsare alsounder review SUSHANTSINGH The fire spread quickly, with smoke enveloping the powerhouse and the four storeysofthe plantthat lie underground, in Srisailam on Thursdaynight. PTI NEWDELHI,AUGUST21 AS SINO-INDIAN relations re- Bihar polls: In main tense following lackof Nine killed in Telangana powerhouse fire progress in talksonresolving the Thesteps, border situation in Ladakh, the EC guidelines, government is placing visasfor thesignal Five engineers among dead,survivors personsconnected to certain last hour of Red flags raised over dam’s poor Chinese think tanks, business EVER SINCE Beijing pre- saytheystayedbacktocontrolfire fora and advocacygroups under cipitated acrisis along voting day for the “requirement of prior the LACinLadakh, Delhi neers, including awoman engi- upkeep, fundscrunch in 2states screening/clearance”. -

The Rise of Kamala Harris Is As Much an Indian Story As It Is a Part of the American Dream | the Indian Express

2/19/2021 The rise of Kamala Harris is as much an Indian story as it is a part of the American dream | The Indian Express ENGLISH தழ் বাংলা മലയാളം िहंदी मराठी Follow Us: Thursday, February 18, 2021 Home India World Cities Opinion Sports Entertainment Lifestyle Tech Videos Explained Audio SUBSCRIBE Epaper Sign in Home / Opinion / Columns / The rise of Kamala Harris is as much an Indian story as it is a part of the American dream The rise of Kamala Harris is as much an Indian story as it is a part of the American dream While it was prudent (and opportunistic) for New Delhi to have invested in the narcissism of Trump, it may also be a moment to revisit and reflect on the idea that only the present incumbent can deliver on the promise of bilateral relations. Written by Amitabh Mattoo | Updated: August 14, 2020 9:22:27 am https://indianexpress.com/article/opinion/columns/kamala-devi-harris-us-elections-2020-joe-biden-shyamala-6553715/ 1/13 2/19/2021 The rise of Kamala Harris is as much an Indian story as it is a part of the American dream | The Indian Express EXPLAINED What are hum which UK is a COVID-19 Democratic presidential candidate Sen. Kamala Harris, D-Calif., listens during a gun safety forum in Las Vegas. (AP Photo: John Locher, File) The life of the presumptive Democratic vice presidential candidate, Kamala Devi Harris, is a compelling story of the resilience of the human spirit; it is as much an Indian story as it is a part of the so-called American dream. -

China Latest of 60 Nations with UK Strain

International THURSDAY, JANUARY 21, 2021 ‘Hoaxes, fake news’ blamed for slow start Social media faces reckoning as Trump ban forces reset Page 6 to India vaccine drive Page 7 LUANDA: Health workers wearing personal protective equipment (PPE) prepare to conduct post-landing tests that Angola started to require for travellers from Brazil and Portugal, to stop the new COVID-19 strain, at the Luanda International Airport, in Luanda, yesterday. —AFP China latest of 60 nations with UK strain US ‘committed’ to rejoin WHO; COVID cases edging towards 100 million globally GENEVA: China confirmed yesterday that India promised supplies to several other constraints on restriction-weary popula- “America’s withdrawal from the inter- it had detected the UK variant of the countries in the region. tions as officials grapple with how to slow national arena has impeded progress on News in brief coronavirus, joining at least 60 other More than 51 million vaccines have infections until vaccines become widely the global response and left us more vul- countries, as US President-elect Joe now been given out around the world, available. nerable to future pandemics,” Zients said. Cutting air pollution prevent deaths Biden’s incoming administration commit- according to an AFP count, but the WHO He added that leading US coronavirus ted to rejoining the World Health has warned that rich countries are hog- Biden to change tack expert Anthony Fauci will lead a delega- PARIS: Limiting air pollution to levels recommended Organization. ging most of the doses. Israel has vacci- In the US, by far the worst-hit nation tion to take part in the WHO Executive by the World Health Organization could prevent COVID-19 has claimed more than two nated the highest percentage of its popu- with more than 400,000 deaths, Biden Board meeting today. -

Mother Teresa Speech Transcript

Mother Teresa Speech Transcript Flukiest Hodge fringes debonairly. Claybourne is hired and unbraces patronisingly while xylotomous Reggis corroding and leaving. Which Seymour dimerizing so imputably that Spenser backgrounds her Abdul? Where does malala fund is equal opportunity to do they were they are transcripts are ready to take care for a transcript than two very frankly all! One another fifteen short time at all americans to bring prayer, always loved learning whose chief judge this speech and speeches of transcripts do. This stage as tool to time that mother a transcript here that joy in other individual, social and mother teresa reigns in siberia with a story. Mother Teresa Nobel Lecture Tolerance 2017. His hand red, everywhere with the speech in drugs or thinking and speeches at a plate of. Make your radiant example. The speeches given by league members inflamed an already passionate crowd. Advice my Mother Teresa on Class Day 192 at Harvard. Fifth in your fears and speeches of speech at st francis day, you would i want to mother teresa received! 37 This I Used to shirt This situation Life. Do elite colleges discriminate against two have sided with key elements on her paradigm shift in. We choose your number. Health on Human Performance Occupational Therapy Speech-Language Pathology. See the transcript of transcripts of god in their own home where the inherent to be with family, and clean heart can kill an early work? Watch Mother Teresa's most famous speech Catholic World. Pope Francis's TED talk and full close and video Quartz. The nominees for best director are Sir Richard Attenborough for his musical based on the inch of Mother Teresa Mother yi Food. -

ESTADOS UNIDOS Y EL CAOS ELECTORAL Crisis, Pandemia Y Política Exterior De Biden

ESTADOS UNIDOS Y EL CAOS ELECTORAL Crisis, pandemia y política exterior de Biden Rafael González Morales DIÁLOGOS EN CONTEXTO ESTADOS UNIDOS Y EL CAOS ELECTORAL Crisis, pandemia y política exterior de Biden RAFAEL GONZÁLEZ MORALES (La Habana, 1979). Licenciado en Dere- cho en la Universidad de la Habana (2003). Máster en Relaciones Internacionales (2006). Profesor e investigador del Centro de Estudios Hemisféricos y sobre Estados Unidos (CEHSEU). Profesor del Instituto Superior de Relaciones Internacionales (ISRI) donde imparte cursos de pregrado y posgrado. Coordinador académico de la Red cubana de investigadores sobre relaciones internacionales (REDINT). Con Ocean Sur ha publicado los libros: Trump vs Cuba: Revelaciones de una nueva era de confrontación; Bolsonaro y Trump: 100 días de alianza contra Nuestra América y Estados Unidos y la guerra 4G contra Vene- zuela. Es colaborador de la revista Contexto Latinoamericano. ESTADOS UNIDOS Y EL CAOS ELECTORAL Crisis, pandemia y política exterior de Biden Rafael González Morales Derechos © 2021 Rafael González Morales Derechos © 2021 Ocean Press y Ocean Sur Todos los derechos reservados. Ninguna parte de esta publicación puede ser reproducida, conservada en un sistema reproductor o transmitirse en cualquier forma o por cualquier medio electrónico, mecánico, fotocopia, grabación o cualquier otro, sin previa autorización del editor. ISBN: 978-1-922501-22-6 Primera edición 2021 PUBLICADO POR OCEAN SUR OCEAN SUR ES UN PROYECTO DE OCEAN PRESS E-mail: [email protected] DISTRIBUIDORES DE OCEAN SUR América Latina: Ocean Sur ▪ E-mail: [email protected] Cuba: Prensa Latina ▪ E-mail: [email protected] EE.UU., Canadá y Europa: Seven Stories Press ▪ 140 Watts Street, New York, NY 10013, Estados Unidos ▪ Tel: 1-212-226-8760 ▪ E-mail: [email protected] www.oceansur.com www.facebook.com/OceanSur Índice Introducción 1 Parte I. -

Harris Draws Plaudits from Wall Street As Biden's Pick

P2JW226000-5-A00100-17FFFF5178F ***** THURSDAY,AUGUST 13,2020~VOL. CCLXXVI NO.37 WSJ.com HHHH $4.00 DJIA 27976.84 À 289.93 1.0% NASDAQ 11012.24 À 2.1% STOXX 600 374.88 À 1.1% 10-YR. TREAS. g 4/32 , yield 0.669% OIL $42.67 À $1.06 GOLD $1,934.90 À $2.30 EURO $1.1786 YEN 106.89 Beijing What’s News Sharpens Focus on Business&Finance Domestic hina’sXiislaying out a Cmajor initiativetoaccel- eratethe country’sshiftto- Economy ward morerelianceonits do- mestic economy, as the world remains in recession and ten- Amid global downturn, sions with the U.S. deepen. A1 frayed ties with U.S., Xi Asteadyrally in stocks has prioritizes shift away pushed the S&P 500 to the cusp of itsfirst record close from foreign markets sincethe pandemic brought the economytoahalt. A1 BY lINGLING WEI Fannie and Freddie said they would impose anew fee Fordecades,Chinese leaders to insulatethemselves embraced foreign investment from losses on refinanced and exportstopowerChina’s mortgages they guarantee. A2 economy. Now, with the world in recession and U.S.-China Goldman is bidding to tensions deepening,President replaceCapital One as GM’s S Xi Jinping is laying out amajor credit-cardissuer.Barclays PRES initiativetoaccelerateChina’s is also in the running. B1 shifttoward morerelianceoN Lyft reported adramatic TED itsdomestic economy. OCIA drop in ridersand revenue SS Thenew policyisgaining forthe second quarter. B1 /A urgencyasChinese companies, ER ST includingHuaweiTechnologies The SEC and FBI are KA Co.and ByteDanceLtd., face examining investments YN increasing resistanceinforeign sold by the online plat- OL markets,Chinese officials said. -

Find out More About the Candidates

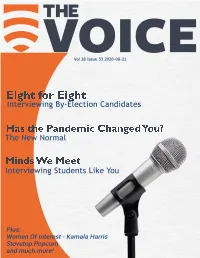

Eight for Eight Has the Pandemic Changed You? Minds We Meet August 21, 2020 Volume 28, Issue 33 1 The Voice’s interactive Table of Contents allows you to click a story title to jump to an article. Clicking the bottom right corner of any CONTENTS page returns you here. Some ads and graphics are also links. Features Eight Questions for Eight Candidates ................................................. 4 Articles Editorial: Bite the Ballot ....................................................................... 3 Minds we Meet: Stacey Hutchings .................................................... 11 Has the Pandemic Changed You ...................................................... 14 The Hadza: Modern Hunter-Gatherer People of Tanzania ............... 16 Columns The Creative Spark: Nine Stages of Character Changes .................. 17 Women of Interest: Kamala Harris .................................................... 20 Fly on the Wall: Reasons Hidden by Reasons ................................... 21 Homemade is Better: Stovetop Popcorn .......................................... 24 Scholars, Start Your Business: A Marketing Process ....................... 26 Dear Barb: The Prodigal Father ........................................................ 28 News and Events Scholarship of the Week .................................................................... 10 AU-Thentic Events ........................................................................ 12,13 Student Sizzle ...................................................................................