Spatial Analysis of the NCAA Basketball Tournament

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Rockbridge Report Thursday, April 7, 2016 Rockbridgereport.Wlu.Edu

Villanova Wildcats win CEOs band together in NCAA National North Carolina against Championship | 8 transgender law | 4 ROCKBRIDGE REPORT Thursday, April 7, 2016 rockbridgereport.wlu.edu What’s Inside Refugees find a home in Rockbridge Anita Filson appointed Rockbridge County’s Refugee Working Group started gathering volunteers, clothes and furniture months before the new judge of Rockbridge County Circuit Court. Congolese family of eight arived in March. See page 2 By John Tompkins Rockbridge Area Health After lengthy flight delays and Center expands space temporarily losing all of their bag- gage, the Msimbwas, a family of and services. eight Congolese refugees, finally See page 3 arrived in town March 11. Their arrival is the culmination of efforts by the Refugee Working Group, an Donald Trump backtracks interfaith coalition that is working to resettle refugees in Rockbridge to appeal to women County. voters after abortion “I’m very happy, it’s a very pleas- comments. ing atmosphere,” said Fahizi See page 4 Msimbwa, the family’s father. “I’m especially happy with the peo- ple who already showed me the school. Everyone’s very welcom- Broadband high-speed i n g .” internet to become Eighty local residents welcomed a reality for BARC their new neighbors at an in- customers. formational meeting at Lylburn Downing Middle School a few See page 5 days after their arrival. “The meeting last night was to learn a little bit about what has With the help of the Refugee Working Group, the Msimbwa family is getting acclimated to life in Lexington. Local residents welcomed their new neighbors at New practice fields an informational meeting at Lylburn Downing Middle School on March 15. -

TABLE of CONTENTS the BIG TEN CONFERENCE CONTENTS Headquarters and Conference Center Media Information

TABLE OF CONTENTS THE BIG TEN CONFERENCE CONTENTS Headquarters and Conference Center Media Information .........................................................................................................2 5440 Park Place • Rosemont, Illinois 60018 • Phone: 847-696-1010 Big Ten Conference History ........................................................................................3 New York City Office 900 Third Avenue, 36th Floor • New York, N.Y., 10022 • Phone: 212-243-3290 Commissioner James E. Delany .................................................................................4 Website: bigten.org Big Life. Big Stage. Big Ten .........................................................................................5 Facebook: /BigTenConference Twitter: @B1GMBBall, @BigTen 2018-19 Composite Schedule .................................................................................. 6-9 BIG TEN STAFF – ROSEMONT Commissioner: James E. Delany 2018-19 TEAM CAPSULES ................................................................................... 10-23 Deputy Commissioner, COO: Brad Traviolia Illinois Fighting Illini ..................................................................................10 Deputy Commissioner, Public Affairs: Diane Dietz Indiana Hoosiers ......................................................................................11 Senior Associate Commissioner, Television Administration: Mark Rudner Iowa Hawkeyes........................................................................................12 Associate -

USA Basketball Men's Pan American Games Media Guide Table Of

2015 Men’s Pan American Games Team Training Camp Media Guide Colorado Springs, Colorado • July 7-12, 2015 2015 USA Men’s Pan American Games 2015 USA Men’s Pan American Games Team Training Schedule Team Training Camp Staffing Tuesday, July 7 5-7 p.m. MDT Practice at USOTC Sports Center II 2015 USA Pan American Games Team Staff Head Coach: Mark Few, Gonzaga University July 8 Assistant Coach: Tad Boyle, University of Colorado 9-11 a.m. MDT Practice at USOTC Sports Center II Assistant Coach: Mike Brown 5-7 p.m. MDT Practice at USOTC Sports Center II Athletic Trainer: Rawley Klingsmith, University of Colorado Team Physician: Steve Foley, Samford Health July 9 8:30-10 a.m. MDT Practice at USOTC Sports Center II 2015 USA Pan American Games 5-7 p.m. MDT Practice at USOTC Sports Center II Training Camp Court Coaches Jason Flanigan, Holmes Community College (Miss.) July 10 Ron Hunter, Georgia State University 9-11 a.m. MDT Practice at USOTC Sports Center II Mark Turgeon, University of Maryland 5-7 p.m. MDT Practice at USOTC Sports Center II July 11 2015 USA Pan American Games 9-11 a.m. MDT Practice at USOTC Sports Center II Training Camp Support Staff 5-7 p.m. MDT Practice at USOTC Sports Center II Michael Brooks, University of Louisville July 12 Julian Mills, Colorado Springs, Colorado 9-11 a.m. MDT Practice at USOTC Sports Center II Will Thoni, Davidson College 5-7 p.m. MDT Practice at USOTC Sports Center II USA Men’s Junior National Team Committee July 13 Chair: Jim Boeheim, Syracuse University NCAA Appointee: Bob McKillop, Davidson College 6-8 p.m. -

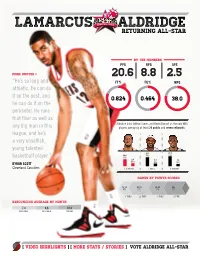

LAMARCUS ALDRIDGE Returning ALL-STAR

LAMARCUS ALDRIDGE returning ALL-STAR BY THE NUMBERS PPG RPG APG MORE QUOTES >> 20.6 8.8 2.5 “He’s so long and FT% FG% MPG athletic. He can do it on the post, and 0.824 0.464 38.0 he can do it on the perimeter. He runs 82+18P47+53P79+21P that floor as well as Aldridge joins LeBron James and Kevin Durant as the only NBA any big man in this players averaging at least 20 points and seven rebounds. league, and he’s a very unselfish, young talented 26.3 29.5 20.6 PPG PPG basketball player.” PPG 8.8 8.1 7.5 RPG BYRON SCOTT RPG RPG Cleveland Cavaliers 21+9L. ALDRIDGE + 27+8+L. JAMES K. DURANT30+7 games by points scored 10-14 15-19 20-24 25+ PTS PTS PTS PTS 606 TIMES+12012 TIMES +909 TIMES+11011 TIMES = rebounding average by month 7.8 8.6 10.8 8+8NOVEMBER +9DECEMBER +11JANUARY [ video highlights ] [ more stats / stories ] VOTE ALDRIDGE ALL-STAr LAMARCUS ALDRIDGE returning ALL-STAR STATS • Is the only player in the NBA averaging at least 20 points and 2.0 turnovers or fewer per game • His three games with at least 30 points and 10 rebounds are tied for most in the NBA with LeBron James and Kobe Bryant • Second in the NBA with three games of at least 25 points, 10 rebounds and five assists, trailing only LeBron James • Ranks eighth in the NBA in scoring (20.6), 19th in rebounding (8.8) and 21st in blocks (1.32) • His eight double-doubles in January are tied for second-most in the league • Leads the team in scoring (20.6) and blocks (1.32), and ranks second in rebounds (8.8) • Among Western Conference post players not already selected to be All-Star starters: - First in scoring (20.6) - First in games with 25 points or more (11) - Second with 10 games of 20-plus points and 10-plus rebounds - One of three players ranked in the top 20 in scoring and rebounding “He was hitting some tough shots. -

Columbia Chronicle College Publications

Columbia College Chicago Digital Commons @ Columbia College Chicago Columbia Chronicle College Publications 11-16-1987 Columbia Chronicle (11/16/1987) Columbia College Chicago Follow this and additional works at: http://digitalcommons.colum.edu/cadc_chronicle Part of the Journalism Studies Commons This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-Noncommercial-No Derivative Works 4.0 License. Recommended Citation Columbia College Chicago, "Columbia Chronicle (11/16/1987)" (Novembe 16, 1987). Columbia Chronicle, College Publications, College Archives & Special Collections, Columbia College Chicago. http://digitalcommons.colum.edu/cadc_chronicle/233 This Book is brought to you for free and open access by the College Publications at Digital Commons @ Columbia College Chicago. It has been accepted for inclusion in Columbia Chronicle by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons @ Columbia College Chicago. -Transcript rule blocks student loan pay-offs By Victoria Pierce saipt. The Rl.'COnJs otl'il.·c rdCrs to this Meanwhile. Annuh 's check has hccn huve gotten it before I registered.·· said. He also >O>id rhe school didn'r as a ··Q rcstrirtion:· sitting in the Financial Aid offil'c for Wells said. know which :-.tudcnts wen:· rcturninJ.! Nearly 350· Columbia studellls an: · "For admission (lo Columbia) all more than two weeks. .. We knew July I rh:~lrhey were gn· and which student!<. were receiving ti unable 10 cnllccrrhcir Pcll GrJnls. ISSC you need is a ievenlh semesrer high By law. a s<:hml can on ly hold a 'IU· ing to start enltm:ing the regulation .·· nanc.:ial aid. or student ltXJ.n chct..-ks due to the rcc.:cm school transcript. -

Vote Goes on to Kennedy Senate

The big thaw , --- :·ol IACCENT: Keenan Revue previews Partly sunny and warmer today with a high of 25. Low tonight 20. Tomorrow's high [VIEWPOINT: Weight jokes not funny temperature is expected to soar to 45. JJ· L---------------------- VOL. XXI, NO. 78 THURSDAY, JANUARY 28, 1988 the independent newspaper serving Notre Dame and Saint Mary's , FBI investigated groups opposed to U.S. foreign policy Associated Press rather than the motives and influence the Congress," Kor sive movements," obtained The FBI's field offices found beliefs of those being inves ten added. 1,320 pages from FBI files no evidence to back up that Washington - A New York tigated." Rep. Don Edwards, D-Calif., through the Freedom of Infor claim, she said, so the focus of based legal group charged And in an interview late Wed chairman of the House subcom mation Act. Many of the pages the investigation was turned Wednesday that the FBI vio nesday, Justice Department mittee on civil and constitu contained blacked-out sen into a "foreign intelligence lated the civil rights of spokesman Pat Korten con tional rights, criticized the tences or paragraphs, and the terrorism" inquiry "even hundreds of people in conduct tended that the Center for FBI's conduct. center said the documents rep though no basis for such ex ing a six-year investigation into Constitutional Rights, which "We want the FBI to catch resent only about a third of the isted." organizations opposed to U.S. has had the FBI documents for spies, terrorists and crooks and government's files. policies in Central America. -

MAB MONTHLY May 2012 FREE

MAB MONTHLY May 2012 FREE RailCats Season Preview Duneland Michigan Recruits Region Softball Midseason Report Boys Hoops All Stars in College Plus, an evening with Bobby Knight www.midamericabroadcasting.com MAB MONTHLY Page 3 MAB ONLINE MAGAZINE MAB Staff family Yet another month rolls around, and another MBA Monthly comes your way. This month we take a look forward at Hank Kilander the Gary SouthShore RailCats 2012 season. Things should be Webmaster Broadcaster exciting in downtown Gary this season as Greg Target leads Staff Writer the team on it’s second American Association campaign. Andy Wielgus does a great job as always taking a look at Rich Sapper the region to Ann Arbor connection in men’s basketball and a Staff Writer Broadcaster historical perspective on Indiana athletes who have set re- Sales cords. Layout & Design Brandon Vickery returns with a mid season look at high school softball in the area, while Hank Kilander gives us a look Bob Potosky Broadcaster at where those Indiana basketball all-stars went to college. We Host only give you a recent list here, the entire list is on our web- Staff Writer site at www.midamericabroadcasting.com. Andy Wielgus We also recap the picks that the Bears and Colts made Broadcaster in this year’s NFL Draft. Of course, as the cover suggests, Rich Host Sapper reflects on his evening with listening to coaching leg- Staff Writer end Bobby Knight speak. JT Hoyo Finally, as always, we ask that you support our spon- Broadcaster sors. Without them, we can not do what we do. -

Racial Double Standards? the Case of Expected Performance and Dismissals of Head Coaches In

Racial double standards? The case of expected performance and dismissals of head coaches in NBA Carlos Gomez-Gonzalez, Julio del Corral, Andrés Maroto ABSTRACT Professional basketball in the US provides an opportunity to test racial differences in the labor market. In contrast to other professional sports, such as baseball or American football, and, more deeply, to other economic sectors, black Americans are represented in influencing positions as head coaches in this competitive setting. The paper investigates the influence of the race of the coach and performance (winning ratio and an efficiency index relative to expectations) on dismissal decisions. The data includes coach- team information over a 20-year period of time in the National Basketball Association (NBA) and the analysis uses several probit models. The results show that black head coaches are more likely to be fired and less prone to quit than white head coaches, ceteris paribus. Both measures of performance (efficiency and victories) also play a significant role in dismissals. Keywords: Basketball, Coaches, Dismissal, Efficiency, Race, Performance, NBA 1 1. Introduction In the words of Samuel Johnson, racial discrimination was a fact "too evident for detection and too gross for aggravation" in the American society of the first part of the 20th century (Arrow, 1998, p. 92). African Americans had a strictly limited access to certain jobs, which prevented them from creating a social network and reaching top positions (Ibarra, 1995). In recent years, although African Americans still face barriers to access leadership jobs in certain sectors, they have successfully scale top positions in professional sports, particularly in basketball. -

Alford Helped Engineer the Most Successful Postseason Run in School History at Missouri State University (Then Known Steve to As Southwest Missouri State)

COACH PROFILES Prior to his service at Iowa, Alford helped engineer the most successful postseason run in school history at Missouri State University (then known STEVE to as Southwest Missouri State). His four-year tenure with the Bears was highlighted by the program’s sixth NCAA Division I Tournament ALFORD appearance in 1999, Missouri State’s first-ever trip to the “Sweet 16” in Alford’s final season at the helm. HEAD COACH • 1st YEAR Missouri State advanced to the NCAA Division I Tournament for the sixth ALMA MATER: INDIANA ’87 time in school history that year, entering the field as the East Regional’s No. 13-seeded team. Alford’s team defeated No. 5-seed Wisconsin (43- 32) and No. 4-seed Tennessee (81-51) to advance to the “Sweet 16” Steve Alford begins his first season as UCLA’s head coach in 2013-14, before losing to top-seeded Duke, 78-61, in the East Regional Semifinal. having compiled a 463-235 record (.663) in 22 seasons as a collegiate head coach. Alford was named the 13th head coach in UCLA men’s Missouri State finished the season 22-11, as Alford had guided the basketball history on March 30, 2013, after having spent the previous Bears to their second 20-plus win season in three years. Prior to Alford’s six seasons at New Mexico. arrival in the fall of 1995, Missouri State had not advanced to the NCAA Tournament since 1992. Alford guided Missouri State to a 24-9 record A four-year standout at Indiana (1984-87) and member of the Hoosiers’ in 1997, including a second-place finish in the Missouri Valley Conference, 1987 NCAA Championship team, Alford competed in the NBA for four as the Bears ended their season in the National Invitation Tournament seasons before embarking on his career as a collegiate head coach. -

Thatcher Demands ·:J Deeds Not Wo.~Ds

r--------------------------------·-- Wotnen's Lib-page 8 VOL. XXI, NO. 116 TUESDAY, MARCH 31, 1987 the independent student newspaper sen·ing ~otre Dame and Saint '-fa11's Dollar Thatcher demands plunges to ·:J deeds not wo.~ds . new low Associated Press all nghts, Gorbachev said. They spoke at a state banquet Associated Press MOSCOW - British Prime in the Grand Kremlin Palace Minister Margaret Thatcher on the third day of Thatcher's NEW YORK -A historic challenged Soviet leader Mik official visit. plunge in the dollar's value put hail Gorbachev on Monday to Thatcher pressed the West's a scare into bull markets produce deeds that match his case for arms control, starting around the world Monday as in words about seeking better re with elimination of medium vestors worried about an un lations abroad and providing range nuclear weapons from restrained decline in the U.S. I greater freedom at home. Europe and restraints on currency and the outside Thatcher took Gorbachev to shorter-range rockets. chance of a trade war. • .pt task specifically on human Her attitudes are an impor The prices of stocks and rights and the withdrawal of tant consideration for Gorbac bonds plunged in Tokyo, Lon Soviet troops from Mghanis hev because Britain has its own don and New York in reaction ·.~"' ~ tan. nuclear arsenal and she has to the dollar's fall. The U.S. \.wJr=::-·- -~~~ .. r "We will reach our judg given strong support to U.S. currency hit its lowest point ments not on intentions or on defense policies. against the Japanese yen since promises but on deeds and on Gorbachev accused the West modern exchange rates were results," she said of Western of including "a package of con established in the late 1940s. -

2006 NCAA Final Four Records Book

360,000 student-athletes 1,200 members 88 championships 23 sports 3 divisions 1 association 10 0 years 1906-2006 NCAA 52045-1/06 F4 06 THE NATIONAL COLLEGIATE ATHLETIC ASSOCIATION P.O. Box 6222, Indianapolis, Indiana 46206-6222 317/917-6222 http://www.ncaa.org January 2006 LSU Sports Information Researched and Compiled By: Gary K. Johnson, Associate Director of Statistics. Cover Photography By: Clarkson and Associates. ON THE COVER Top row (left to right): Francisco Garcia, Sidney Wicks, Sean May and Bruce Weber. Second row: Roy Williams, Artis Gilmore, Lute Olson and Patrick Ewing & John Thompson. Third row: Bill Bradley, Deron Williams & Raymond Felton, Christian Laettner and Tom Izzo. Bottom row: Rashad McCants, Wilt Chamberlain, Rick Pitino and Luther Head. Distributed to Division I men’s basketball sports information directors and confer- ence publicity directors. NCAA, NCAA logo and National Collegiate Athletic Association are registered marks of the Association and use in any manner is prohibited unless prior approval is obtained from the Association. Copyright, 2006, by the National Collegiate Athletic Association. Printed in the United States of America. ISSN 0267-1017 NCAA 52045-1/06 2 2005 NCAA FINAL FOUR Contents The Final Four...................................................... 7 The Early Rounds ................................................. 35 The Tournament ................................................... 49 The Coaches ........................................................ 91 Attendance and Sites ........................................... 111 The Tournament Field ........................................... 127 Index................................................................... 246 Photo by Rich Clarkson/NCAA Photos CONTENTS 3 New to this Book AP No. 1 vs. No. 2 in the Championship Game list .......................................................... 21 Top 5 Team Tournament Scoring Margins for a Series ....................................................... 56 Photo by Brian Gadbery/NCAA Photos All-time No. -

Southeastern Conference Basketball Is a "Tradition of Excellence"

Former Auburn standout Marquis Daniels attempts a shot for the Indiana Pacers. Southeastern Conference Basketball is a "Tradition of Excellence" Did you know? ... The SEC is one of just two confer- ences in the nation to have all of its teams ranked at least one week in the AP top 25 since 1999-2000. • The RPI has ranked the SEC the No.1 overall conference in all of college basketball in five of the past 12 seasons. The and the • Every SEC team has played in the NCAA Tournament at least once since • 400 former SEC players have been selected the 2002 season. in the NBA Draft since 1949. • The SEC record for most Sweet 16 ap- • 110 players have been taken in the NBA pearances in an NCAA Tournament is Draft since 1990, including 12 in 2012, four set in 1986 when Auburn, Alabama, eight in 2007 and seven each in 2010, 2005 Kentucky and LSU advanced past the and 2004. first two rounds and in 1996 when Ar- kansas, Georgia, Kentucky and Missis- • 55 players have been selected in the first sippi State did it. round of the NBA Draft since 1990. • Eight SEC players were chosen in • 29 players chosen as lottery picks in the the 2012 NBA Draft. Over the last five NBA Draft since the Draft Lottery was in- NBA Drafts, 35 SEC players have heard cepted in 1985, including four in 2010 and their names called. Seven were chosen three in both 2012 and 2007. in 2010. 138 ond to None Did you know? ..