Racial Double Standards? the Case of Expected Performance and Dismissals of Head Coaches In

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Bill Cartwright

Bill Cartwright Bill Cartwright is a winner! He was in his basketball career, he is in his business career and he continues to be a winner in his family life. Cartwright was a 7’1” NBA center was a dominant physical presence for 3 teams. He was drafted in the 1st round of the 1979 NBA draft, #3 overall, by the New York Knicks. He made an All-Star Game appearance in his rookie season and was named to the All Rookie First Team. He was named team captain of the Knicks but 4 separate fractures to his foot began to slow him steps. Bill was traded to the Chicago Bulls in 1988 and it was here that he fully established himself as a presence. He was once again named team captain and led the Bulls to 3 consecutive NBA championships in 1991, 1992, and 1993. In 1994, he moved on as a free agent to the Seattle SuperSonics where he spent the final season of his 16 year playing career. In 1996, Bill rejoined the Chicago Bulls as an assistant coach and won two more NBA championships with the team in 1997 and 1998. In 2001, he took over the Bulls’ head coach where he remained until 2003, coaching a team that had been stripped of its best players. He moved on from Chicago to be an assistant coach with the New Jersey Nets and Phoenix Suns before spending the 2013 season coaching in Japan and 2014 as head coach of the Mexican National Team. Cartwright has firmly established himself in the business world as the owner of a car dealership and a restaurant and he recently divested himself from a successful security services firm. -

Men's Basketball Coaching Records

MEN’S BASKETBALL COACHING RECORDS Overall Coaching Records 2 NCAA Division I Coaching Records 4 Coaching Honors 31 Division II Coaching Records 36 Division III Coaching Records 39 ALL-DIVISIONS COACHING RECORDS Some of the won-lost records included in this coaches section Coach (Alma Mater), Schools, Tenure Yrs. WonLost Pct. have been adjusted because of action by the NCAA Committee 26. Thad Matta (Butler 1990) Butler 2001, Xavier 15 401 125 .762 on Infractions to forfeit or vacate particular regular-season 2002-04, Ohio St. 2005-15* games or vacate particular NCAA tournament games. 27. Torchy Clark (Marquette 1951) UCF 1970-83 14 268 84 .761 28. Vic Bubas (North Carolina St. 1951) Duke 10 213 67 .761 1960-69 COACHES BY WINNING PERCENT- 29. Ron Niekamp (Miami (OH) 1972) Findlay 26 589 185 .761 1986-11 AGE 30. Ray Harper (Ky. Wesleyan 1985) Ky. 15 316 99 .761 Wesleyan 1997-05, Oklahoma City 2006- (This list includes all coaches with a minimum 10 head coaching 08, Western Ky. 2012-15* Seasons at NCAA schools regardless of classification.) 31. Mike Jones (Mississippi Col. 1975) Mississippi 16 330 104 .760 Col. 1989-02, 07-08 32. Lucias Mitchell (Jackson St. 1956) Alabama 15 325 103 .759 Coach (Alma Mater), Schools, Tenure Yrs. WonLost Pct. St. 1964-67, Kentucky St. 1968-75, Norfolk 1. Jim Crutchfield (West Virginia 1978) West 11 300 53 .850 St. 1979-81 Liberty 2005-15* 33. Harry Fisher (Columbia 1905) Fordham 1905, 16 189 60 .759 2. Clair Bee (Waynesburg 1925) Rider 1929-31, 21 412 88 .824 Columbia 1907, Army West Point 1907, LIU Brooklyn 1932-43, 46-51 Columbia 1908-10, St. -

NBA Commissioner's Comments on Older Coaches Is a Lesson to All

NBA Commissioner’s Comments On Older Coaches Is A Lesson To All Employers Returning To Work Insights 6.08.20 The National Basketball Association made national headlines last week by announcing its season would resume later this summer. That same night, league commissioner Adam Silver also garnered national attention – and criticism – when he said that older coaches may not be able to sit with their teams on the sidelines during games. In an interview on TNT’s “Inside the NBA,” Silver said that “some older coaches may not be able to be the bench coach in order to protect them.” Silver’s comments immediately drew criticism, including from one of the “older coaches,” 65-year- old Alvin Gentry, the coach of the New Orleans Pelicans. “That doesn't make sense. How can I coach that way?” Gentry told ESPN’s Ramona Shelbourne, adding that he does not think that older coaches should be “singled out.” As noted in one of our firm's recent newsletter articles, a recent AARP study found that individuals 65 or older comprised 19.3% of the U.S. workforce. Employers are understandably concerned about their older employees, considering that the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) has reported that 80% of COVID-19-related deaths reported in the U.S. have been in adults 65 years of age and older. The controversy around Silver’s comments, however, should be a lesson for employers who are trying to figure out how to return to work safely. Trying to “protect” older employees may leave employers susceptible to age discrimination lawsuits. -

Soft Power Played on the Hardwood: United States Diplomacy Through Basketball

Claremont Colleges Scholarship @ Claremont Pitzer Senior Theses Pitzer Student Scholarship 2015 Soft oP wer Played on the Hardwood: United States Diplomacy through Basketball Joseph Bertka Eyen Pitzer College Recommended Citation Eyen, Joseph Bertka, "Soft oP wer Played on the Hardwood: United States Diplomacy through Basketball" (2015). Pitzer Senior Theses. 86. https://scholarship.claremont.edu/pitzer_theses/86 This Open Access Senior Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Pitzer Student Scholarship at Scholarship @ Claremont. It has been accepted for inclusion in Pitzer Senior Theses by an authorized administrator of Scholarship @ Claremont. For more information, please contact [email protected]. SOFT POWER PLAYED ON THE HARDWOOD United States Diplomacy through Basketball by Joseph B. Eyen Dr. Nigel Boyle, Political Studies, Pitzer College Dr. Geoffrey Herrera, Political Studies, Pitzer College A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Degree of Bachelor of Arts with Honors in Political Studies Pitzer College Claremont, California 4 May 2015 2 ABSTRACT This thesis demonstrates the importance of basketball as a form of soft power and a diplomatic asset to better achieve American foreign policy, which is defined and referred to as basketball diplomacy. Basketball diplomacy is also a lens to observe the evolution of American power from 1893 through present day. Basketball connects and permeates foreign cultures and effectively disseminates American influence unlike any other form of soft power, which is most powerfully illustrated by the United States’ basketball relationship with China. American basketball diplomacy will become stronger and connect with more countries with greater influence, and exist without relevant competition, until the likely rise of China in the indefinite future. -

For Immediate Release Former Nba Star Johnny Moore

FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE FORMER NBA STAR JOHNNY MOORE NAMED HEAD COACH OF THE NEW ABA UNIVERSAL CITY, TX SERAPHIM™ BASKETBALL TEAM San Antonio, Texas, July 20, 2016 -- One of the American Basketball Association’s newest teams, located in Universal City, Texas, The Seraphim™ is pleased to announce former NBA star Johnny Moore as its’ new Head Coach. Johnny Moore played a total of 10 years in the NBA, all of which were with the San Antonio Spurs. When he finished his NBA career, he was the all- time assist leader in Spurs history, handing out 3,865 assists while appearing in 519 games. He averaged 9.4 points, 7.4 assists and 3.0 rebounds per game. Johnny’s best season was during the 1984-1985 NBA season, where he averaged 12.8 points, 10 assists, 4.8 rebounds and 2.79 steals in 82 games. Johnny Moore had his number (00) retired by the San Antonio Spurs, joining an elite group of former players including Avery Johnson, Bruce Bowen, David Robinson, George Gervin, James Silas and Sean Elliott. Johnny played four seasons at the University of Texas, and was twice named to the All-Southwest Conference First Team. He led the SWC in assists during two different seasons, and holds the record for the most assists in a single game by a SWC player. During the 1978-79 season, he handed out 19 assists in two different games. In his junior year, Texas won the NIT and Johnny was named the tournament MVP. Johnny has been dedicated to serving youth and improving the San Antonio community, since joining the San Antonio Spurs Community Relations team in 1993. -

Hawks' Trio Headlines Reserves for 2015 Nba All

HAWKS’ TRIO HEADLINES RESERVES FOR 2015 NBA ALL-STAR GAME -- Duncan Earns 15 th Selection, Tied for Third Most in All-Star History -- NEW YORK, Jan. 29, 2015 – Three members of the Eastern Conference-leading Atlanta Hawks -- Al Horford , Paul Millsap and Jeff Teague -- headline the list of 14 players selected by the coaches as reserves for the 2015 NBA All-Star Game, the NBA announced today. Klay Thompson of the Golden State Warriors earned his first All-Star selection, joining teammate and starter Stephen Curry to give the Western Conference-leading Warriors two All-Stars for the first time since Chris Mullin and Tim Hardaway in 1993. The 64 th NBA All-Star Game will tip off Sunday, Feb. 15, at Madison Square Garden in New York City. The game will be seen by fans in 215 countries and territories and will be heard in 47 languages. TNT will televise the All-Star Game for the 13th consecutive year, marking Turner Sports' 30 th year of NBA All- Star coverage. The Hawks’ trio is joined in the East by Dwyane Wade and Chris Bosh of the Miami Heat, the Chicago Bulls’ Jimmy Butler and the Cleveland Cavaliers’ Kyrie Irving . This is the 11 th consecutive All-Star selection for Wade and the 10 th straight nod for Bosh, who becomes only the third player in NBA history to earn five trips to the All-Star Game with two different teams (Kareem Abdul-Jabbar, Kevin Garnett). Butler, who leads the NBA in minutes (39.5 per game) and has raised his scoring average from 13.1 points in 2013-14 to 20.1 points this season, makes his first All-Star appearance. -

2020-21 COLORADO BASKETBALL Colorado Buffaloes Coaches Year-By-Year Conference Overall Season Conf

colorado buffaloes Coaching Records COLORADO COACHING CHRONOLOGY No. Coach Years Coached Seasons Won Lost Percent no coach ..................................................................1902-1906 5 18 15 .545 1. Frank R. Castleman ..................................................1907-1912 6 32 22 .592 2. John McFadden ........................................................1913-1914 2 10 9 .526 3. James N. Ashmore ...................................................1915-1917 3 16 10 .615 4. Melbourne C. Evans ..................................................1918 1 9 2 .818 5. Joe Mills ..................................................................1919-1924 6 30 24 .556 6. Howard Beresford ....................................................1925-1933 9 76 52 .594 7. Henry P. Iba ............................................................1934 1 9 8 .529 8. Earl “Dutch” Clark ....................................................1935 1 3 9 .250 9. Forrest B. Cox ..........................................................1936-1950 13 147 89 .623 10. H. B. Lee..................................................................1950-1956 6 63 74 .459 11. Russell “Sox” Walseth ..............................................1956-1976 20 261 245 .516 12. Bill Blair ..................................................................1976-1981 5 67 69 .493 13. Tom Apke ................................................................1981-1986 5 59 81 .421 14. Tom Miller ...............................................................1986-1990 4 35 -

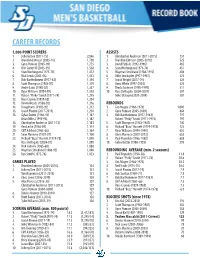

Career Records 1,000-Point Scorers Assists 1

CAREER RECORDS 1,000-POINT SCORERS ASSISTS 1. Johnny Dee (2011-15) 2,046 1. Christopher Anderson (2011-2015) 757 2. Brandon Johnson (2005-10) 1,790 2. Brandon Johnson (2005-2010) 525 3. Gyno Pomare (2005-09) 1,725 3. David Fizdale (1992-1996) 465 4. Olin Carter III (2015-19) 1,558 4. Stan Washington (1971-74) 451 5. Stan Washington (1971-74) 1,472 5. Wayman Strickland (1988-1992) 408 6. Nick Lewis (2001-06) 1,453 6. Mike Stockapler (1977-1981) 374 7. Bob Bartholomew (1977-81) 1,394 7. Isaiah Wright (2017-19) 326 8. Scott Thompson (1983-87) 1,379 8. Dana White (1997-2001) 325 9. Andre Laws (1998-02) 1,337 9. Brock Jacobsen (1995-1999) 311 10. Ryan Williams (1994-99) 1,318 10. Ross DeRogatis (2004-2007) 307 11. Robert “Pinky” Smith (1971-74) 1,295 Mike McGrain (2001-2004) 307 12. Russ Cravens (1959-63) 1,234 13. Kelvin Woods (1988-92) 1,216 REBOUNDS 14. Doug Harris (1992-95) 1,212 1. Gus Magee (1966-1970) 1,000 15. Isaiah Pineiro (2017-2019) 1,210 2. Gyno Pomare (2005-2009) 864 16. Gylan Dottin (1988-93) 1,187 3. Bob Bartholomew (1977-1981) 797 Brian Miles (1995-98) 1,187 Robert “Pinky” Smith (1971-1974) 797 18. Christopher Anderson (2011-15) 1,181 5. Scott Thompson (1983-1987) 740 19. Ken Leslie (1956-59) 1,174 6. Richard “Buzz” Harnett (1974-1978) 723 20. Cliff Ashford (1963-66) 1,164 7. Ryan Williams (1994-1999) 653 21. Sean Flannery (1992-97) 1,100 8. -

44-Spring 2020 Alumni Calumet Compressed Postal Edition

As we celebrate our 22nd Anniversary, WE NEED YOUR SUPPORT! So please JOIN the Weequahic High School Alumni Association or RENEW your membership. We look forward to the next 22 years of providing opportunity to the students at Weequahic High School. ALUMNI MEMBERSHIP Alumni - $25 Orange & Brown - $50 Ergo - $100 Sagamore - $500 Legend - $1,000 BY CHECK Send a check (made out to WHSAA) to: WHS Alumni Association P.O. Box 494, Newark, NJ 07101 BY CREDIT CARD To pay by credit card, call our Executive Director Myra Lawson at (973) 923-3133 Please enjoy reading our 44th edition - Spring 2020 Alumni Calumet Newsletter 1 ON THE INSIDE: Alumni Association 22nd Anniversary / Hall of Distinction Ceremony Remembering Hal Braff, Co-Founder, WHS Alumni Association 2019 Weequahic High School Alumni Scholarship Recipients Alumni Association, Vision, Goals and Accomplishments Ruby Baskerville, 1961, elected new Alumni Co-President A Son Pays Tribute to His Dad: Alvin Attles, Basketball Hall of Fame Weequahic High School’s new Allied Health Academy Victor Parsonnet, 1941, Inducted into NJ Hall of Fame Brian Logan, 1982, inducted into Newark Athletic Hall of Fame Larry Layton, 1963, Inducted into NJ Boxing Hall of Fame Jacob Toporek, 1963, Impact on the Jewish Community in NJ Two Weequahic Centenarians: Philip Agism and Thelma Gottlieb 2019 Alumni Association Highlights Lenny Wallen’s Pleasantdale Kosher Market in West Orange The story of Mildred’s Corset Shop, originally on Bergen Street 2020 Reunion Information and 2019 Reunion Pictures The Passing of Newark’s Mayor Kenneth Gibson “In Loving Memory” of alumni who recently passed away 2019 Hall of Distinction Ceremony Collage Page 2 Celebrating our 22nd Anniversary with Hall of Distinction Ceremony On the evening of October 17, 2019, 250 alumni Hisani Dubose Sheila Oliver 1971 1970 and friends gathered at the Renaissance Newark Airport Hotel to celebrate the 22nd anniversary of the Weequahic High School Alumni Association and the induction of 20 distinguished alumni into its Hall of Distinction. -

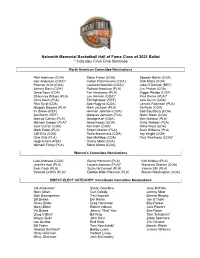

Naismith Memorial Basketball Hall of Fame Class of 2021 Ballot * Indicates First-Time Nominee

Naismith Memorial Basketball Hall of Fame Class of 2021 Ballot * Indicates First-Time Nominee North American Committee Nominations Rick Adelman (COA) Steve Fisher (COA) Speedy Morris (COA) Ken Anderson (COA)* Cotton Fitzsimmons (COA) Dick Motta (COA) Fletcher Arritt (COA) Leonard Hamilton (COA)* Jake O’Donnell (REF) Johnny Bach (COA) Richard Hamilton (PLA) Jim Phelan (COA) Gene Bess (COA) Tim Hardaway (PLA) Digger Phelps (COA) Chauncey Billups (PLA) Lou Henson (COA)* Paul Pierce (PLA)* Chris Bosh (PLA) Ed Hightower (REF) Jere Quinn (COA) Rick Byrd (COA) Bob Huggins (COA) Lamont Robinson (PLA) Muggsy Bogues (PLA) Mark Jackson (PLA) Bo Ryan (COA) Irv Brown (REF) Herman Johnson (COA) Bob Saulsbury (COA) Jim Burch (REF) Marques Johnson (PLA) Norm Sloan (COA) Marcus Camby (PLA) George Karl (COA) Ben Wallace (PLA) Michael Cooper (PLA)* Gene Keady (COA) Chris Webber (PLA) Jack Curran (COA) Ken Kern (COA) Willie West (COA) Mark Eaton (PLA) Shawn Marion (PLA) Buck Williams (PLA) Cliff Ellis (COA) Rollie Massimino (COA) Jay Wright (COA) Dale Ellis (PLA) Bob McKillop (COA) Paul Westhead (COA)* Hugh Evans (REF) Danny Miles (COA) Michael Finley (PLA) Steve Moore (COA) Women’s Committee Nominations Leta Andrews (COA) Becky Hammon (PLA) Kim Mulkey (PLA) Jennifer Azzi (PLA) Lauren Jackson (PLA)* Marianne Stanley (COA) Swin Cash (PLA) Suzie McConnell (PLA) Valerie Still (PLA) Yolanda Griffith (PLA)* Debbie Miller-Palmore (PLA) Marian Washington (COA) DIRECT-ELECT CATEGORY: Contributor Committee Nominations Val Ackerman* Simon Gourdine Jerry McHale Marv -

University of San Diego Men's Basketball Media Guide 1992-1993

University of San Diego Digital USD Basketball (Men) University of San Diego Athletics Media Guides 1993 University of San Diego Men's Basketball Media Guide 1992-1993 University of San Diego Athletics Department Follow this and additional works at: https://digital.sandiego.edu/amg-basketball-men UNIVERSITY OF SAN DIEGO EROS '92-93 MEN'S BASKETBALL Senior Co-Captains Geoff Probst (#11) • Gylan Dottin (#24) RADIO AND TELEVISION ROSTER GEOFF ROCCO #11 PROBST #33 RAFFO 5' 11" 165 lbs. 6'9" 220 lbs. Senior Guard Freshman Center Corona de! Mar,CA Salinas, CA DAVID NEAL #13 FIZDALE #35 MEYER 6'2" 170 lbs. 6'3" 200 lbs. Freshman Guard Junior Guard Los Angeles, CA Scottsdale, AZ DOUG BRIAN HARRIS #21 #40 BRUSO 6'0" 174 lbs. 6'7" 200 lbs. Sophomore Guard Freshman Forward Chandler, AZ S. Lake Tahoe, CA----~~ JOE CHRISTOPHER #23 TEMPLE #44 GRANT 6'4" 208 lbs. 6' 8" 215 lbs. Junior Guard/Forward Junior Forward/Center San Diego, CA S. Lake Tahoe, CA GYLAN BROOKS #24 DOTTIN #50 BARNHARD 6'5" 220 lbs. 6'9" 220 lbs. Senior Forward Junior Center Santa Ana, CA Escondido, CA VAL RYAN #30 HILL #55 HICKMAN 6'4" 210 lbs. 6'6" 255 lbs. Freshman Guard/Forward Freshman Forward Tucson, AZ Los Angeles, CA SEAN #32 FLANNERY UNIVERSITY OF SA N DI EG O 6'7" 200 lbs. Freshman Guard :TOREROS Tucson, AZ CONTENTS Page I USD TORERO'S MESSAGE TO THE MEDIA The 1992-93 USD Basketball Media Guide was prepared and 1992-93 Basketball Yearbook edited by USD Sports Information Director Ted Gosen for use by & Media Guide media covering Torero basketball. -

Al Attles, Warriors NBA Legend

VOL 94 Issue # 26 EDITOR: JANIENE LANGFORD • PHOTOGRAPHER: ED AVELAR FEBRUARY 8, 2016 Mike Cobb & Rick Hansen prepare to demonstrate their “eggs-cellent” omelet flipping skills. Call To Order Past President Debby De Angelis, filling in forPresident Andy Krake, called the meeting to order at 12:15 p.m…The Pledge of Allegiance was led by Mike Cobb, followed by a Patriotic Song led by Douglas Den Hartog and Chuck Horner…The Thought for the Day was delivered by George Pacheco: “Teamwork makes our Hayward Rotary Club a success. We are partners in our work, which in turns makes us winners and champions in our community!” Introduction of Visiting Rotarians and Guests Mark Salinas introduced Visiting Rotarian Bob Tucknott from the Dublin Rotary Club. (Bob joined us a little late, but he was here!)... Debby De Angelis introduced her husband, David De Angelis; and Joan McDermott, CSU East Bay’s Director of Athletics… Janiene Langford introduced Dr. Stacy Thompson, Vice President of Academic Services at Chabot College and Chair of Alameda Commission on the Status of Women... Kim Huggett introduced Camilo Pascua, Director of Global Engineering Services for Impax; and Jim Morrison, CEO of Lit San Leandro…Ashton Simmons introduced Dr. Timothy Gay, Executive Vice President of the Health Center for Life Chiropractic College West. Guests were welcomed with a rousing rendition of our favorite song,“HELLO!” Announcements: l Tom Gratny reported that Salvation Army needs a new commercial can opener. The old can opener is shredding the cans and getting metal in the food. Rotarians immediately took up a collection.