Kehinde Wiley's Interventions Into the Construction of Black Masculine Identity

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

KEHINDE WILEY Bibliography Selected Publications 2020 Drew

KEHINDE WILEY Bibliography Selected Publications 2020 Drew, Kimberly and Jenna Wortham. Black Futures. New York: One World, 2020. 2016 Robertson, Jean and Craig McDaniel. Themes of Contemporary Art: Visual Art after 1980, Fourth Edition. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2016. 2015 Tsai, Eugenie and Connie H. Choi. Kehinde Wiley: A New Republic. New York: Brooklyn Museum, 2015. Sans, Jérôme. Kehinde Wiley: The World Stage: France 1880-1960. Paris: Galerie Daniel Templon, 2015. 2014 Crutchfield, Margo Ann. Aspects of the Self: Portraits of Our Times. Virginia: Moss Arts Center, Virginia Tech Center for the Arts, 2014. Oliver, Cynthia and Rogge, Mike. Kehinde Wiley: The World Stage: Haiti. Culver City, California: Roberts & Tilton, 2014. 2013 Eshun, Ekow. Kehinde Wiley, The World Stage: Jamaica. London: Stephen Friedman, 2013. Kandel, Eric R. Eye to I: 3,000 Years of Portraits. New York: Katonah Museum of Art, 2013. Kehinde Wiley, Memling. Phoenix: Phoenix Art Museum, 2013. 2012 Golden, Thelma, Robert Hobbs, Sara E. Lewis, Brian Keith Jackson, and Peter Halley. Kehinde Wiley. New York: Rizzoli, 2012. Haynes, Lauren. The Bearden Project. New York: The Studio Museum in Harlem, 2012. Weil, Dr. Shalva, Ruth Eglash, and Claudia J. Nahson. Kehinde Wiley, The World Stage: Israel. Culver City: Roberts & Tilton, 2012. 2010 Wiley, Kehinde, Gayatri Sinha, and Paul Miller. Kehinde Wiley, The World Stage: India, Sri Lanka. Chicago: Rhona Hoffman Gallery, 2011. 2009 Wiley, Kehinde, Brian Keith. Jackson, and Kimberly Cleveland. Kehinde Wiley, The World Stage: Brazil = O Estágio Do Mundo. Culver City: Roberts & Tilton, 2009. Jackson, Brian Keith, and Krista A. Thompson. Black Light. Brooklyn: Powerhouse Books, 2009. -

Kehinde Wiley October 2016 LAMENTATION 20 October 2016 - 15 January 2017

Press Release Kehinde Wiley October 2016 LAMENTATION 20 October 2016 - 15 January 2017 Tuesday-Sunday 10am – 6pm INFORMATIONS www.petitpalais.paris.fr The Petit Palais is holding the first solo exhibition in France of work by Afro-American artist Kehinde Wiley. The exhibition features a previously unseen series of ten monumental works, in the form of stained glass windows and paintings, showcased at the heart of the museum’s permanent collections. Kehinde Wiley draws on the tradition of classical painting masters such as Titian, Van Dyck, Ingres and David to create portraits drenched in colour and abounding in adornment. The subjects are young black and mixed-race people, anonymous models encountered during ad- hoc street castings. The result is a collision where art history and popular culture come face to face. The artist eroticizes the invisible, those traditionally excluded from representations of power, endowing them with hero status. His work takes the vocabulary of power and prestige in a new direction, oscillating between politically-charged critique and an avowed fascination with the luxury and bombast of our society’s symbols. For the Petit Palais show, Kehinde Wiley continues to explore religious iconography, with references to Christ and, for the first time, the figure of the Virgin. Six stained glass windows will be installed on a hexagonal structure in the large format gallery. They will Kehinde Wiley, Mary, Comforter of the Afflicted be accompanied by three monumental paintings displayed on I, 2016 Courtesy Galerie Templon, Paris et Bruxelles the walls of one of the ground floor rooms housing 19th century ©Kehinde Wiley Studio collections. -

Reading Print Ads for Designer Children's Clothing

University of Massachusetts Amherst ScholarWorks@UMass Amherst Communication Graduate Student Publication Communication Series October 2009 The mother’s gaze and the model child: Reading print ads for designer children’s clothing Chris Boulton UMass, Amherst, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.umass.edu/communication_grads_pubs Part of the Communication Commons Boulton, Chris, "The mother’s gaze and the model child: Reading print ads for designer children’s clothing" (2009). Advertising & Society Review. 5. Retrieved from https://scholarworks.umass.edu/communication_grads_pubs/5 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Communication at ScholarWorks@UMass Amherst. It has been accepted for inclusion in Communication Graduate Student Publication Series by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks@UMass Amherst. For more information, please contact [email protected]. ABSTRACT This audience analysis considers how two groups of mothers, one affluent and mostly white and the other low-income and mostly of color, responded to six print ads for designer children’s clothing. I argue that the gender and maternal affiliations of these women—which coalesce around their common experience of the male gaze and a belief that children’s clothing represents the embodied tastes of the mother—are ultimately overwhelmed by distinct attitudes towards conspicuous consumption, in-group/out-group signals, and even facial expressions. I conclude that, when judging the ads, these mothers engage in a vicarious process referencing their own daily practice of social interaction. In other words, they are auditioning the gaze through which others will view their own children. KEY WORDS advertising, fashion, race, mothers, children BIO Chris Boulton is a doctoral student in Communication at the University of Massachusetts, Amherst. -

Developing Multicultural Intelligence Through the Work of Kehinde Wiley Melanie L

Virginia Commonwealth University VCU Scholars Compass Art Education Publications Dept. of Art Education 2009 Developing Multicultural Intelligence through the Work of Kehinde Wiley Melanie L. Buffington Virginia Commonwealth University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: http://scholarscompass.vcu.edu/arte_pubs Part of the Art Education Commons, Bilingual, Multilingual, and Multicultural Education Commons, and the Teacher Education and Professional Development Commons Copyright © 2009 Journal of Cultural Research in Art Education Downloaded from http://scholarscompass.vcu.edu/arte_pubs/2 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Dept. of Art Education at VCU Scholars Compass. It has been accepted for inclusion in Art Education Publications by an authorized administrator of VCU Scholars Compass. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Developing Multicultural Intelligence through the Work of Kehinde Wiley Developing Multicultural Intelligence through the Work of Kehinde Wiley Melanie L. Buffington ABSTRACT . Through a revzew ofcurrent events) contemporary ideas on multicultural education) and the art ofKehinde Wiley) this article argues that using the work ofcontemporary artists is one way to introduce pre-service teachers to the complex issues of multiculturalism) race) and culture in contemporary society. By learning about contemporary artists whose work overtly relates to race and culture) pre-service teachers may become more comfortable with the realities of the multicultural schools they encounter throughout their careers. Additionally) the article introduces portraiture methodology as a means ofunderstanding interactions in university classrooms) especially as they relate to pre-service teacher education. Thus) this article explores the roots ofcultural violence through the lens ofmulticultural education and pre-service teacher education. -

Grade One Session One – Exploration of Different Genres in Art

Grade One Session One – Exploration of Different Genres in Art First Grade Overview: The first grade program will explore various genres in art history. Building upon the concept of portraiture examined in kindergarten, we will begin the first session by comparing traditional and contemporary examples of portraiture as an artistic genre. In subsequent sessions, we will examine the genres of landscape and still life through paintings and prints that embrace cultural, international and gender differences. In the fourth and final session, the subject will return to the idea of portraiture looking ahead to the thematic concepts of rituals and traditions examined in the second grade program. To begin the session, you may briefly recall some of the works of art studied during the previous year and/or the concepts of portraiture. While not a requirement, it provides a nice introduction for the start of the program and gets the children back in the practice of looking at art. Grade One Session One First Image (NOTE: DO NOT SHARE IMAGE TITLE OR SOURCE YET) Jacques-Louis David, Napoleon Crossing the Alps, 1801 Oil on canvas, 102 x 87 inches Collection: Chateau du Malmaison, Rueil Malmaison, France (Napoleon and his wife Josephine lived here; it is now a museum) Project the image onto the SMARTboard. Remind the students how a portrait sometimes reveals how an artist sees a person and is often a likeness of an individual. A portrait can also depict how someone would like to be seen. Both wealthy and important people often have portraits painted of them in a certain environment or centered around an important event. -

Kehinde Wiley Prepared by Traci Timmons, SAM Librarian

Bibliography for Kehinde Wiley Prepared by Traci Timmons, SAM Librarian Resources are available in the Bullitt Library (Seattle Art Museum, Fifth Floor, South Building). 1. Beyond Bling: Voices of Hip-Hop in Art. McLendon, Matthew. Sarasota; London: The John and Mable Ringling Museum of Art; Scala Publications Ltd., 2011. N 6490 S27 M35. 2. Kehinde Wiley: About Page. Kehinde Wiley Studio. http://kehindewiley.com/about/. 3. Kehinde Wiley. Golden, Thelma et al. New York: Rizzoli, 2012. ND 237 W5487 G75 2012. 4. Kehinde Wiley: A New Republic. Tsai, Eugenie et al. Brooklyn, NY: Brooklyn Museum, 2015. ND 237 W5487 T93 2015. 5. Kehinde Wiley: A New Republic website. Brooklyn Museum. https://www.brooklynmuseum.org/exhibitions/kehinde_wiley_new_republic/. 6. Kehinde Wiley: An Economy of Grace website. PBS. http://www.pbs.org/program/kehinde-wiley-economy-grace/ 7. Kehinde Wiley: Columbus. Columbus, Ohio; Los Angeles: Columbus Museum of Art; Roberts & Tilton, 2006. ND 237 W5487 C85 2006. 8. Kehinde Wiley: The World Stage: Brazil = O Estágio do Mundo. Culver City, Calif.: Roberts & Tilton, 2009. ND 237 W5487 R83 2009. 9. Kehinde Wiley: The World Stage: France 1880-1960 = La Scene Mondiale: La France 1880-1960. Paris: Galerie Daniel Templon, 2015. ND 237 W5487 D26 2015. 10. Kehinde Wiley: The World Stage: Haiti = Sèn Mondyal la Ayiti. Culver City, Calif.: Roberts & Tilton, 2015. ND 237 W5487 R83 2015. 11. Kehinde Wiley: The World Stage: India, Sri Lanka. Chicago: Rhona Hoffman Gallery, 2011. ND 237 W5487 R57 2011. 12. Kehinde Wiley: The World Stage: Israel = Bamat ha-ʻolam: Yisra'el.́ Culver City, Calif.: Roberts & Tilton, 2012. -

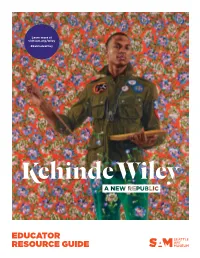

Educator Resource Guide Overview

Learn more at visitsam.org/wiley #KehindeWiley EDUCATOR RESOURCE GUIDE OVERVIEW ABOUT THE EXHIBITION Organized by the Brooklyn Museum, this exhibition brings together over 50 of Kehinde Wiley’s portraits in large-scale paintings, bronze sculptures, and stained glass from the last fifteen years. Wiley is one of the leading contemporary American artists, reworking the grand portraiture traditions of Western culture. Wiley began his first series of portraits in the early 2000s during a residency at the Studio Museum in Harlem. He set out to recast young African American men from the neighborhood in the style and manner of traditional history painting. Since then he has also painted pop culture stars, although his primary focus remains ordinary people in their own clothes and style. Trained at Yale in the 1990s, Wiley brings a strong understanding of traditional painting techniques to an interest in contemporary issues of identity and power. Wiley’s portraits recreate the poses of European aristocrats, contrasting elaborate and ornate backgrounds with contemporary subjects in their own clothes. These choices draw attention to the lack of images of people of color in historical and contemporary works. SAM’s Educator Resource Guide highlights three works from the exhibition and explores ideas about how these works examine personal and cultural identities. ABOUT THE ARTIST “Going to the museums [in Los Angeles] and increasingly throughout the world as an adult, you start to realize that those images of people of color just don’t exist. And there’s something to be said about simply being visible.” Kehinde Wiley, CBC radio interview for Q, February 20, 2014 Born in Los Angeles in 1977, Kehinde Wiley began attending art classes on the weekend with his brother when he was eleven. -

Kehinde Wiley,” the Wall Street Journal, April 25, 2012

! O’Rourke, Meghan. “Kehinde Wiley,” The Wall Street Journal, April 25, 2012. On studying art in the forests of St. Petersburg at age 12, his hyperdecorative style, and combining grandeur with chance FAR FROM HERE Artist Kehinde Wiley in his studio in Beijing, with works from his recent Armory Show. He lives part time in China, where he is able to paint free from distractions. Portrait by Mark Leong Painter Kehinde Wiley, 35, has enjoyed the kind of meteoric career that led Andy Warhol to quip about 15 minutes of fame. When he was a child, his mother, a linguist, enrolled Wiley and his siblings in art and literary programs as a way to help keep them safe in the rough South Central Los Angeles neighborhood where they lived. Early on Wiley gravitated toward the visual arts; when he was 12, he went to the U.S.S.R. on an arts exchange program, thanks to a foundation grant funded by financier Michael Milken, which ignited his interest in global politics. After Yale's MFA program, Wiley got a coveted residency at the Studio Museum in Harlem, where he started establishing himself as an art-world luminary. Drawn in by the "peacocking" of Harlem street life, he began making luxurious, Old Master–influenced portraits of young black men in street clothes. Subsequently, in his "The World Stage" series, he broadened his focus to include large-scale portraits of young men from regions around the globe. His work references Titian as easily as it does pop culture, and addresses stereotypes of race and class, power and history. -

Annual Report 2018-2019

FY18 ANNUAL REPORT ALL OF US TOGETHER 2 GLAAD 02 Key GLAAD Initiatives ANNUAL REPORT 03 Mission Statement FY18 05 President & CEO’s Message 06 Jan-Sept 2018 Highlights KEY 10 News & Rapid Response ACCOMPLISHMENTS 12 GLAAD Media Institute (GMI) 14 Spanish-Language and Latinx Media 16 Youth Engagement 18 Events 22 Transgender Media Program 24 Voter Education & Engagement GLAAD BY 28 GLAAD at Work THE NUMBERS 29 Letter from the Treasurer 30 Financial Summary INVESTORS 34 GLAAD Supporters & DIRECTORY 36 Giving Circles 39 Staff 40 Board of Directors 2 3 KEY GLAAD INITIATIVES MISSION GLAAD NEWS & RAPID RESPONSE GLAAD serves as a resource to journalists and news outlets in print, broadcast, and online to ensure that the news media is accurately and fairly representing LGBTQ people in its reporting. As the world’s largest GLAAD MEDIA INSTITUTE (GMI) lesbian, gay, bisexual, Through training, consulting, and research—including annual resources like the Accelerating Acceptance report and the GLAAD Studio Responsibility Index—GMI enables everyone from students to professionals, transgender, and queer journalists to spokespeople to build the core skills and techniques that effectuate positive cultural change. GLAAD CAMPUS AMBASSADOR PROGRAM (LGBTQ) media advocacy GLAAD Campus Ambassadors are a volunteer network of university/college LGBTQ and ally students who work with GLAAD and within their local communities to build an LGBTQ movement to accelerate acceptance and end hate. organization, GLAAD is GLAAD MEDIA AWARDS at the forefront of cultural The GLAAD Media Awards recognize and honor media for their fair, accurate, and inclusive representations of the LGBTQ community and the issues that affect their lives. -

Fadulu, Lola. “Kehinde Wiley on Self-Doubt and How He Made It As a Painter,” the Atlantic, November 4, 2018

Fadulu, Lola. “Kehinde Wiley on Self-Doubt and How He Made It as a Painter,” The Atlantic, November 4, 2018. Evan Agostini / Invision / AP / Katie Martin / The Atlantic By age 12, Kehinde Wiley had a reputation in his Los Angeles neighborhood for being a talented artist. Teachers at his school recommended him for a program during which he spent the summer of 1989 in Russia with 50 Soviet kids and 50 other Americans, creating murals, learning the Russian language and culture, hiking, swimming, and picking mushrooms. “It was a strange, magical time,” he recalls. Wiley went on to study art at the San Francisco Art Institute and Yale. He now has a studio in Brooklyn, and Barack Obama chose him to paint a lively portrait of the former president that now hangs in the National Portrait Gallery. I recently spoke with Wiley about traveling to Nigeria to meet his father for the first time after having painted portraits of him for years, dealing with criticism, and the importance of slowing down. This interview has been lightly edited and condensed for length and clarity. Lola Fadulu: What was your mom’s work schedule like? Kehinde Wiley: My mother, while raising six kids, had a number of small- business activities. The most prominent one in my memory was sort of like a junk store. She would be away, in the earliest years, much of the day. Then she would be around more in the late afternoons, evenings. When we weren’t in school, we would be around the shop, and I remember learning Spanish dealing with a lot of the customers there. -

Finding Aid to the Historymakers ® Video Oral History with Thelma Golden

Finding Aid to The HistoryMakers ® Video Oral History with Thelma Golden Overview of the Collection Repository: The HistoryMakers®1900 S. Michigan Avenue Chicago, Illinois 60616 [email protected] www.thehistorymakers.com Creator: Golden, Thelma Title: The HistoryMakers® Video Oral History Interview with Thelma Golden, Dates: August 9, 2016 Bulk Dates: 2016 Physical 13 uncompressed MOV digital video files (6:10:28). Description: Abstract: Museum director and curator Thelma Golden (1965 - ) became the director and chief curator of the Studio Museum in Harlem in 2005, having served as a curator at the Whitney Museum of American Art in the 1990s. Golden was interviewed by The HistoryMakers® on August 9, 2016, in New York, New York. This collection is comprised of the original video footage of the interview. Identification: A2016_006 Language: The interview and records are in English. Biographical Note by The HistoryMakers® Museum director and curator Thelma Golden was born on September 22, 1965 in Queens, New York. In 1983, she graduated from the New Lincoln School, where she trained as a curatorial apprentice at the Metropolitan Museum of Art in her senior year. In 1987, she earned her B.A. degree in art history and African American studies from Smith College. Golden worked first as a curatorial intern at the Studio Museum in Harlem in 1987, then as a curatorial assistant at the Whitney Museum of American Art in 1988. From 1989 to 1991, she worked as the visual arts director for the Jamaica Arts Center in Queens, New York, where she curated eight shows. Golden was then appointed branch director of the Whitney Museum of American Art’s Philip Morris branch in 1991 and curator of the Whitney Museum of American Art in 1996. -

Aimed at Helping Dot.Ccm Business

MIN ItB}(IDESBIlL *************************3-DIGIT078 s 1071159037SP 20000619 edl ep 2 IIILAURA K JONES, ASS1TANT MGR 330G < NALCENBOOKS a 42 MOUNT PLEASANT AVE (r) WHARTON NJ 07885-2120 135 Lu Z HI iilmIli.1,1..1..1.1,,.1.1...11,.1,111,,,ilul..1.111,111 Vol. 9 No. 31 THE NEWS MAGAZINE OF THE MEDIA August 9, 1999 $3.50 Andy Sareyan Ann Moore (standing), Susan Wylan MARKET INDICATORS National TV: Steady It's quiet now, but fourth-quarter scatte- keeps trickling in. Dot.coms, autos anrd packaged goods pac- ing well. Net Cable: Chilling Sales execs take sum- mer break as third quar- ter wraps and fourth quarter paces 25 per- Time Inc. plans a cent over upfront. Wall Street ups and downs new magazine causirg some jitters about end -of -year aimed at helping dot.ccm business. women cope Spot TV: Quiet Lazy summer days are with life Page 4 here. September is open, but October buys will likely get crunched as the expected fourth-quar- ter dcllars rush in. Radio: Sold out Fourth-quarter network scatter is all but sold out, diving rates through the roof. Up- front for first quarter next year is wide open. Magazines: Waiting Software companies are holding off from buying ads in third and Might of the Right FCC Gives Thumbs Up to LMAspage 5 fourth quarter. Huge spending expected in As former House Speaker Newt first quarter 2000 after Y2K stare is over. 'Gingrich hits the airwaves, Hearst Buys 'Chronicle, Sells Magspage 6 3 2> conservative talk radio is as strong W 7 as it was back in '94.