Grade One Session One – Exploration of Different Genres in Art

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Kehinde Wiley October 2016 LAMENTATION 20 October 2016 - 15 January 2017

Press Release Kehinde Wiley October 2016 LAMENTATION 20 October 2016 - 15 January 2017 Tuesday-Sunday 10am – 6pm INFORMATIONS www.petitpalais.paris.fr The Petit Palais is holding the first solo exhibition in France of work by Afro-American artist Kehinde Wiley. The exhibition features a previously unseen series of ten monumental works, in the form of stained glass windows and paintings, showcased at the heart of the museum’s permanent collections. Kehinde Wiley draws on the tradition of classical painting masters such as Titian, Van Dyck, Ingres and David to create portraits drenched in colour and abounding in adornment. The subjects are young black and mixed-race people, anonymous models encountered during ad- hoc street castings. The result is a collision where art history and popular culture come face to face. The artist eroticizes the invisible, those traditionally excluded from representations of power, endowing them with hero status. His work takes the vocabulary of power and prestige in a new direction, oscillating between politically-charged critique and an avowed fascination with the luxury and bombast of our society’s symbols. For the Petit Palais show, Kehinde Wiley continues to explore religious iconography, with references to Christ and, for the first time, the figure of the Virgin. Six stained glass windows will be installed on a hexagonal structure in the large format gallery. They will Kehinde Wiley, Mary, Comforter of the Afflicted be accompanied by three monumental paintings displayed on I, 2016 Courtesy Galerie Templon, Paris et Bruxelles the walls of one of the ground floor rooms housing 19th century ©Kehinde Wiley Studio collections. -

Developing Multicultural Intelligence Through the Work of Kehinde Wiley Melanie L

Virginia Commonwealth University VCU Scholars Compass Art Education Publications Dept. of Art Education 2009 Developing Multicultural Intelligence through the Work of Kehinde Wiley Melanie L. Buffington Virginia Commonwealth University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: http://scholarscompass.vcu.edu/arte_pubs Part of the Art Education Commons, Bilingual, Multilingual, and Multicultural Education Commons, and the Teacher Education and Professional Development Commons Copyright © 2009 Journal of Cultural Research in Art Education Downloaded from http://scholarscompass.vcu.edu/arte_pubs/2 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Dept. of Art Education at VCU Scholars Compass. It has been accepted for inclusion in Art Education Publications by an authorized administrator of VCU Scholars Compass. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Developing Multicultural Intelligence through the Work of Kehinde Wiley Developing Multicultural Intelligence through the Work of Kehinde Wiley Melanie L. Buffington ABSTRACT . Through a revzew ofcurrent events) contemporary ideas on multicultural education) and the art ofKehinde Wiley) this article argues that using the work ofcontemporary artists is one way to introduce pre-service teachers to the complex issues of multiculturalism) race) and culture in contemporary society. By learning about contemporary artists whose work overtly relates to race and culture) pre-service teachers may become more comfortable with the realities of the multicultural schools they encounter throughout their careers. Additionally) the article introduces portraiture methodology as a means ofunderstanding interactions in university classrooms) especially as they relate to pre-service teacher education. Thus) this article explores the roots ofcultural violence through the lens ofmulticultural education and pre-service teacher education. -

Kehinde Wiley Prepared by Traci Timmons, SAM Librarian

Bibliography for Kehinde Wiley Prepared by Traci Timmons, SAM Librarian Resources are available in the Bullitt Library (Seattle Art Museum, Fifth Floor, South Building). 1. Beyond Bling: Voices of Hip-Hop in Art. McLendon, Matthew. Sarasota; London: The John and Mable Ringling Museum of Art; Scala Publications Ltd., 2011. N 6490 S27 M35. 2. Kehinde Wiley: About Page. Kehinde Wiley Studio. http://kehindewiley.com/about/. 3. Kehinde Wiley. Golden, Thelma et al. New York: Rizzoli, 2012. ND 237 W5487 G75 2012. 4. Kehinde Wiley: A New Republic. Tsai, Eugenie et al. Brooklyn, NY: Brooklyn Museum, 2015. ND 237 W5487 T93 2015. 5. Kehinde Wiley: A New Republic website. Brooklyn Museum. https://www.brooklynmuseum.org/exhibitions/kehinde_wiley_new_republic/. 6. Kehinde Wiley: An Economy of Grace website. PBS. http://www.pbs.org/program/kehinde-wiley-economy-grace/ 7. Kehinde Wiley: Columbus. Columbus, Ohio; Los Angeles: Columbus Museum of Art; Roberts & Tilton, 2006. ND 237 W5487 C85 2006. 8. Kehinde Wiley: The World Stage: Brazil = O Estágio do Mundo. Culver City, Calif.: Roberts & Tilton, 2009. ND 237 W5487 R83 2009. 9. Kehinde Wiley: The World Stage: France 1880-1960 = La Scene Mondiale: La France 1880-1960. Paris: Galerie Daniel Templon, 2015. ND 237 W5487 D26 2015. 10. Kehinde Wiley: The World Stage: Haiti = Sèn Mondyal la Ayiti. Culver City, Calif.: Roberts & Tilton, 2015. ND 237 W5487 R83 2015. 11. Kehinde Wiley: The World Stage: India, Sri Lanka. Chicago: Rhona Hoffman Gallery, 2011. ND 237 W5487 R57 2011. 12. Kehinde Wiley: The World Stage: Israel = Bamat ha-ʻolam: Yisra'el.́ Culver City, Calif.: Roberts & Tilton, 2012. -

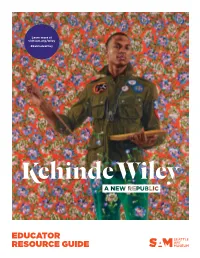

Educator Resource Guide Overview

Learn more at visitsam.org/wiley #KehindeWiley EDUCATOR RESOURCE GUIDE OVERVIEW ABOUT THE EXHIBITION Organized by the Brooklyn Museum, this exhibition brings together over 50 of Kehinde Wiley’s portraits in large-scale paintings, bronze sculptures, and stained glass from the last fifteen years. Wiley is one of the leading contemporary American artists, reworking the grand portraiture traditions of Western culture. Wiley began his first series of portraits in the early 2000s during a residency at the Studio Museum in Harlem. He set out to recast young African American men from the neighborhood in the style and manner of traditional history painting. Since then he has also painted pop culture stars, although his primary focus remains ordinary people in their own clothes and style. Trained at Yale in the 1990s, Wiley brings a strong understanding of traditional painting techniques to an interest in contemporary issues of identity and power. Wiley’s portraits recreate the poses of European aristocrats, contrasting elaborate and ornate backgrounds with contemporary subjects in their own clothes. These choices draw attention to the lack of images of people of color in historical and contemporary works. SAM’s Educator Resource Guide highlights three works from the exhibition and explores ideas about how these works examine personal and cultural identities. ABOUT THE ARTIST “Going to the museums [in Los Angeles] and increasingly throughout the world as an adult, you start to realize that those images of people of color just don’t exist. And there’s something to be said about simply being visible.” Kehinde Wiley, CBC radio interview for Q, February 20, 2014 Born in Los Angeles in 1977, Kehinde Wiley began attending art classes on the weekend with his brother when he was eleven. -

Kehinde Wiley,” the Wall Street Journal, April 25, 2012

! O’Rourke, Meghan. “Kehinde Wiley,” The Wall Street Journal, April 25, 2012. On studying art in the forests of St. Petersburg at age 12, his hyperdecorative style, and combining grandeur with chance FAR FROM HERE Artist Kehinde Wiley in his studio in Beijing, with works from his recent Armory Show. He lives part time in China, where he is able to paint free from distractions. Portrait by Mark Leong Painter Kehinde Wiley, 35, has enjoyed the kind of meteoric career that led Andy Warhol to quip about 15 minutes of fame. When he was a child, his mother, a linguist, enrolled Wiley and his siblings in art and literary programs as a way to help keep them safe in the rough South Central Los Angeles neighborhood where they lived. Early on Wiley gravitated toward the visual arts; when he was 12, he went to the U.S.S.R. on an arts exchange program, thanks to a foundation grant funded by financier Michael Milken, which ignited his interest in global politics. After Yale's MFA program, Wiley got a coveted residency at the Studio Museum in Harlem, where he started establishing himself as an art-world luminary. Drawn in by the "peacocking" of Harlem street life, he began making luxurious, Old Master–influenced portraits of young black men in street clothes. Subsequently, in his "The World Stage" series, he broadened his focus to include large-scale portraits of young men from regions around the globe. His work references Titian as easily as it does pop culture, and addresses stereotypes of race and class, power and history. -

Fadulu, Lola. “Kehinde Wiley on Self-Doubt and How He Made It As a Painter,” the Atlantic, November 4, 2018

Fadulu, Lola. “Kehinde Wiley on Self-Doubt and How He Made It as a Painter,” The Atlantic, November 4, 2018. Evan Agostini / Invision / AP / Katie Martin / The Atlantic By age 12, Kehinde Wiley had a reputation in his Los Angeles neighborhood for being a talented artist. Teachers at his school recommended him for a program during which he spent the summer of 1989 in Russia with 50 Soviet kids and 50 other Americans, creating murals, learning the Russian language and culture, hiking, swimming, and picking mushrooms. “It was a strange, magical time,” he recalls. Wiley went on to study art at the San Francisco Art Institute and Yale. He now has a studio in Brooklyn, and Barack Obama chose him to paint a lively portrait of the former president that now hangs in the National Portrait Gallery. I recently spoke with Wiley about traveling to Nigeria to meet his father for the first time after having painted portraits of him for years, dealing with criticism, and the importance of slowing down. This interview has been lightly edited and condensed for length and clarity. Lola Fadulu: What was your mom’s work schedule like? Kehinde Wiley: My mother, while raising six kids, had a number of small- business activities. The most prominent one in my memory was sort of like a junk store. She would be away, in the earliest years, much of the day. Then she would be around more in the late afternoons, evenings. When we weren’t in school, we would be around the shop, and I remember learning Spanish dealing with a lot of the customers there. -

30 Americans West Coast Debut at Tacoma Art Museum: Unforgettable

MEDIA RELEASE August 2, 2016 Media Contact: Julianna Verboort, 253-272-4258 x3011 or [email protected] 30 Americans West Coast debut at Tacoma Art Museum: Unforgettable Tacoma, WA - The critically acclaimed, nationally traveling exhibition 30 Americans makes its West Coast debut at Tacoma Art Museum (TAM) this fall. Featuring 45 works drawn from the Rubell Family Collection in Miami – one of the largest private contemporary art collections in the world – 30 Americans will be on view from September 24, 2016 through January 15, 2017. The exhibition showcases paintings, photographs, installations, and sculptures by prominent African American artists who have emerged since the 1970s as trailblazers in the contemporary art scene. The works explore identity and the African American experience in the United States. The exhibition invites viewers to consider multiple perspectives, and to reflect upon the similarities and differences of their own experiences and identities. “The impact of this inspiring exhibition comes from the powerful works of art produced by major artists who have significantly advanced contemporary art practices in our country for three generations," said TAM's Executive Director Stephanie Stebich. "We've been working for four years to bring this exhibition to our community. The stories these works tell are more relevant than ever as we work toward understanding and social change. Art plays a pivotal role in building empathy and resolving conflict." Stebich added, "TAM is a safe space for difficult conversations through art. We plan to hold open forums and discussions during the run of this exhibition offering ample opportunity for community conversations about the role of art, the history of racism, and the traumatic current events.” The museum’s exhibition planning team issued an open call in March to convene a Community Advisory Committee. -

Oral History Interview with Kehinde Wiley, 2010 September 29

Oral history interview with Kehinde Wiley, 2010 September 29 Contact Information Reference Department Archives of American Art Smithsonian Institution Washington. D.C. 20560 www.aaa.si.edu/askus Transcript Preface The following oral history transcript is the result of a tape-recorded interview with Kehinde Wiley on 2010 September 28. The interview took place at Sean Kelly Gallery in New York, NY, and was conducted by Anne Louise Bayly Berman for the Archives of American Art, Smithsonian Institution. Kehinde Wiley and Anne Louise Bayly Berman have reviewed the transcript and have made corrections and emendations. The reader should bear in mind that he or she is reading a transcript of spoken, rather than written, prose. Interview ANNE LOUISE BAYLY BERMAN: This is Anne Louise Berman interviewing Kehinde Wiley at the Sean Kelly Gallery on West 29th Street on September 28th – KEHINDE WILEY: Two thousand ten. MS. BERMAN: Two thousand ten. So now you were born in L.A. MR. WILEY: I was born in Los Angeles. MS. BERMAN: Okay. MR. WILEY: My mother’s from Texas. MS. BERMAN: Okay. MR. WILEY: Small town outside of Waco called Downsville. And my father’s from Nigeria. And so I guess I’m properly African-American. MS. BERMAN: [Laughs.] Yes. MR. WILEY: They met in university back in the ‘70s. And I didn’t grow up with my father. He – they separated before I was born. At age 20 I went to go find him in Nigeria. And after much toil, I finally figured out exactly where he was. And there’s something about seeing your father for the first time – my mother destroyed all pictures of him. -

Kehinde Wiley Rumors of War New York Unveiling

COMMUNICATIONS DIVISION VIRGINIA MUSEUM OF FINE ARTS 200 N. Boulevard I Richmond, Virginia 23220 www.VMFA.museum/pressroom FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE Sept. 27, 2019 Artist Kehinde Wiley unveils Rumors of War sculpture in Times Square, New York, to be permanently installed at the Virginia Museum of Fine Arts Rumors of War © 2019 Kehinde Wiley. Used by permission. Presented by Times Square Arts in partnership with the Virginia Museum of Fine Art and Sean Kelly, New York. Photographer: Kylie Corwin for Kehinde Wiley. TODAY, FRIDAY, SEPTEMBER 27, 2019 — Times Square Arts, the Virginia Museum of Fine Arts (VMFA) and Sean Kelly, New York unveiled artist Kehinde Wiley’s first monumental public sculpture Rumors of War in Times Square, New York on the Broadway Plaza between 46th and 47th Streets. Video content from the event is available HERE. Photos will be available at the same link shortly. User: TSQA Password: press Artwork Details: Kehinde Wiley Rumors of War, 2019 Patinated bronze with stone pedestal Overall: 27’4 7/8” H x 25’5 7/8” L x 15’9” 5/8” W Following its presentation in Times Square, Rumors of War will be permanently installed on historic Arthur Ashe Boulevard in Richmond at the entrance to the VMFA, a recent acquisition to the museum’s world-class collection. An installation ceremony will take place at VMFA on December 10, 2019. Kehinde Wiley, a world-renowned visual artist, is best known for his vibrant portrayals of contemporary African- American and African-Diasporic individuals that subvert the hierarchies and conventions of European and American portraiture. -

The Evening Standard

The London Evening Standard Kehinde Wiley on his first UK solo show for Frieze week 11 October 2013 Ben Luke Kehinde Wiley on his first UK solo show for Frieze week For his first UK show, hip-hop’s portrait artist Kehinde Wiley has turned his attention to the Jamaican dancehall with dazzling results. It’s all about history and identity, he tells Ben Luke Kingston parade: Alexander I, Emperor of Russia, after Gerard’s 1817 painting Kehinde Wiley is already a big art world star. He’s the South Central LA kid who became the darling of the hip-hop scene, with A-list celebrities queuing up to be painted by him; he’s a fixture in American museums, with paintings that reach six figures at auction; and he has studios around the world, in New York, Beijing and Dakar. The London Evening Standard Kehinde Wiley on his first UK solo show for Frieze week 11 October 2013 Ben Luke Britain has been slower to notice him but that’s set to change as London bursts into brighter-than-usual colour for Frieze week and Wiley’s first UK solo show opens in Mayfair. Once seen, these paintings aren’t forgotten: images of young black people, mainly men, in poses from grand historical portraits, with dazzling flower-patterned backgrounds. In the new show, all the paintings are based on great British portraits by Joseph Wright of Derby and other masters, and the backdrops are like William Morris on acid. “I’ve turned the volume up on notions of acceptable colour and taste,” the 36-year-old artist tells me from Beijing. -

Kehinde Wiley: a New Republic VIRGINIA MUSEUM of FINE ARTS | Art Education

Kehinde Wiley: A New Republic VIRGINIA MUSEUM OF FINE ARTS | Art Education Explore Kehinde Wiley’s work through the lens of VMFA’s encyclopedic permanent collection! No. 1 Fantastic patterns often take the place of more traditional settings in the background of Wiley’s portraits. Intricately designed textiles, wallpaper, and decorative objects such as ceramics are sources of inspiration for the artist. Compare Wiley’s background in Two Heroic Sisters of the Grassland to the 17th- century Chinese blue-and-white porcelain Drug Jar. These types of jars were used to store herbs and other natural remedies including one called Diacarth, a medicinal paste used to calm an upset stomach. Drug Jar, 1662-1722, Chinese, porcelain with underglaze. Gift of Dr. and Mrs. John A. Pope. © 2016 Virginia Museum of Fine Arts. Kehinde Wiley (American, born 1977), Two Heroic Sisters of the Grassland, 2011, Oil on canvas. Hort Family Collection. © Kehinde Wiley No. 2 Radiant gold and architectural frames surround these two images. The Virgin Mary, Mother of God in the Christian faith, is shown in Andrea di Bartolo’s painting as large and majestic, ascending into heaven surrounded by a group of angels. The opposite work shows a bare-chested, tattooed gentleman holding an art history book, the cover of which features none other than Mary holding her child, Jesus Christ. Wiley’s subject gives the sign of a benediction or blessing with his other hand. The Assumption of the Virgin with St. Thomas and Two Donors (Ser Palamedes and His Son Matthew), ca. 1390s, Andrea di Bartolo (Italian, 1360-1428), tempera on wood. -

Kehinde Wiley's Interventions Into the Construction of Black Masculine Identity

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Carolina Digital Repository The Power of Décor: Kehinde Wiley’s Interventions into the Construction of Black Masculine Identity Shahrazad A. Shareef A thesis submitted to the faculty of the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in the Department of Art. Chapel Hill 2010 Approved by: Dr. John Bowles Dr. Dorothy Verkerk Dr. Pika Ghosh © 2010 Shahrazad A. Shareef ALL RIGHTS RESERVED ii ABSTRACT Contemporary artist Kehinde Wiley creates portraits that employ conventional representations of young black males in varying degrees of hip-hop inspired attire placed against intricate, botanical patterns. Criticism of the artist’s work claims that the subjects of his imagery are the old master paintings which often function as the artist’s templates. It also implicitly suggests that Wiley accepts racialized typologies. In my analysis of the artist’s distinct style, I argue that these images confront the construction of black masculinity and its reduction to a limited set of possibilities through its decorative system. I discuss the black male subjects in combination with the decor woven around their bodies. Interpreting botanical ornamentation as a visual analogue to American consumerism, I expand the subject of the paintings to include contemporary culture. These patterns act as social capital and function as an extension of the body. In addition to light, prints recalling an ethnic “other” and hip-hop attire, Wiley’s decorative elements imbue the sitters with power and prestige through their references to history and their transgressions through race, class and gender.