The Interview-Document Nexus Recovering Histories of LGBTI Military Service in Australia Noah Riseman

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Rhodesian Crisis in British and International Politics, 1964

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by University of Birmingham Research Archive, E-theses Repository THE RHODESIAN CRISIS IN BRITISH AND INTERNATIONAL POLITICS, 1964-1965 by CARL PETER WATTS A thesis submitted to the University of Birmingham For the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY School of Historical Studies The University of Birmingham April 2006 University of Birmingham Research Archive e-theses repository This unpublished thesis/dissertation is copyright of the author and/or third parties. The intellectual property rights of the author or third parties in respect of this work are as defined by The Copyright Designs and Patents Act 1988 or as modified by any successor legislation. Any use made of information contained in this thesis/dissertation must be in accordance with that legislation and must be properly acknowledged. Further distribution or reproduction in any format is prohibited without the permission of the copyright holder. Abstract This thesis uses evidence from British and international archives to examine the events leading up to Rhodesia’s Unilateral Declaration of Independence (UDI) on 11 November 1965 from the perspectives of Britain, the Old Commonwealth (Canada, Australia, and New Zealand), and the United States. Two underlying themes run throughout the thesis. First, it argues that although the problem of Rhodesian independence was highly complex, a UDI was by no means inevitable. There were courses of action that were dismissed or remained under explored (especially in Britain, but also in the Old Commonwealth, and the United States), which could have been pursued further and may have prevented a UDI. -

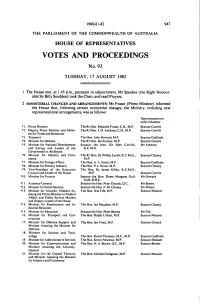

Votes and Proceedings

1980-81-82 947 THE PARLIAMENT OF THE COMMONWEALTH OF AUSTRALIA HOUSE OF REPRESENTATIVES VOTES AND PROCEEDINGS No. 93 TUESDAY, 17 AUGUST 1982 1 The House met, at 1.45 p.m., pursuant to adjournment. Mr Speaker (the Right Honour- able Sir Billy Snedden) took the Chair, and read Prayers. 2 MINISTERIAL CHANGES AND ARRANGEMENTS: Mr Fraser (Prime Minister) informed the House that, following certain ministerial changes, the Ministry, including new representational arrangements, was as follows: Representationin other Chamber *1. Prime Minister The Rt Hon. Malcolm Fraser, C.H., M.P. Senator Carrick *2. Deputy Prime Minister and Minis- The Rt Hon. J. D. Anthony, C.H., M.P. Senator Carrick ter for Trade and Resources *3. Treasurer The Hon. John Howard, M.P. Senator Guilfoyle *4. Minister for Defence The Rt Hon. lan Sinclair, M.P. Senator Durack *5. Minister for National Development Senator the Hon. Sir John Carrick, Mr Anthony and Energy and Leader of the K.C.M.G. Government in the Senate *6. Minister for Industry and Com- The Rt Hon. Sir Phillip Lynch, K.C.M.G., Senator Chaney merce M.P. *7. Minister for Foreign Affairs The Hon. A. A. Street, M.P. Senator Guilfoyle *8. Minister for Primary Industry The Hon. P. J. Nixon, M.P. Senator Chancy *9. Vice-President of the Executive The Hon. Sir James Killen, K.C.M.G., Council and Leader of the House M.P. Senator Carrick *10. Minister for Finance Senator the Hon. Dame Margaret Guil- Mr Howard foyle, D.B.E. *11. Attorney-General Senator the Hon. -

GEOPOLITICS of the 2016 AUSTRALIAN DEFENSE WHITE PAPER and ITS PREDECESSORS Bert Chapman Purdue University, [email protected]

Purdue University Purdue e-Pubs Libraries Faculty and Staff choS larship and Research Purdue Libraries 4-25-2016 GEOPOLITICS OF THE 2016 AUSTRALIAN DEFENSE WHITE PAPER AND ITS PREDECESSORS Bert Chapman Purdue University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: http://docs.lib.purdue.edu/lib_fsdocs Part of the Australian Studies Commons, Comparative Politics Commons, Defense and Security Studies Commons, Economic Policy Commons, Geography Commons, History of the Pacific Islands Commons, Industrial Organization Commons, International and Area Studies Commons, International Relations Commons, Military History Commons, Military Studies Commons, Peace and Conflict Studies Commons, Political Economy Commons, Political History Commons, Public Economics Commons, and the Public Policy Commons Recommended Citation Bert Chapman."Geopolitics of the 2016 Australian Defense White Paper and Its Predecessors." Geopolitics, History, and International Relations, 9 (1)(2017): 17-67. This document has been made available through Purdue e-Pubs, a service of the Purdue University Libraries. Please contact [email protected] for additional information. Geopolitics, History, and International Relations 9(1) 2017, pp. 17–67, ISSN 1948-9145, eISSN 2374-4383 GEOPOLITICS OF THE 2016 AUSTRALIAN DEFENSE WHITE PAPER AND ITS PREDECESSORS BERT CHAPMAN [email protected] Purdue University, West Lafayette, IN ABSTRACT. Australia released the newest edition of its Defense White Paper, describing Canberra’s current and emerging national security priorities, on February 25, 2016. This continues a tradition of issuing defense white papers since 1976. This work will examine and analyze the contents of this document as well as previous Australian defense white papers, scholarly literature, and political statements assess- ing their geopolitical significance. -

Hansard 27 Nov 1997

27 Nov 1997 Ministerial Statement 4895 THURSDAY, 27 NOVEMBER 1997 properties; and (c) not permit the project to proceed without full community support. Petitions received. Mr SPEAKER (Hon. N. J. Turner, Nicklin) read prayers and took the chair at 9.30 a.m. SALARIES AND ALLOWANCES TRIBUNAL REPORT Hon. D. E. BEANLAND (Indooroopilly— PETITIONS Attorney-General and Minister for Justice) The Clerk announced the receipt of the (9.33 a.m.): On 19 August 1997 I tabled the following petitions— 17th report of the Salaries and Allowances Tribunal along with a copy of advice from the Solicitor-General relating to a dissenting report Political Advertising from Sir James Killen. In response to a From Mr Beattie (23 petitioners) request from Sir James, I now table a copy of requesting the House to immediately cease his letter to me on 10 September 1997 in politically motivated, taxpayer-funded which he responds to the Solicitor-General's advertising being used solely to promote the advice. I table also further advice dated 24 National and Liberal Parties and request November 1997 from the Solicitor-General on instead that the money go toward (a) this matter. improving funding for TAFE to give young people an opportunity to gain important skills training; (b) increasing resources to improve PAPER the police presence in Queensland towns and The following paper was laid on the communities; and (c) improving health services table— to reduce accident and emergency waiting Minister for Emergency Services and Minister times and ballooning waiting lists in our public for Sport (Mr Veivers)— hospitals. Response to Public Accounts Committee Report No. -

Commonwealth Arts Policy and Administration

Parliament of Australia Department of Parliamentary Services Parliamentary Library Information, analysis and advice for the Parliament BACKGROUND NOTE www.aph.gov.au/library 7 May 2009, 2008–09 Commonwealth arts policy and administration Dr John Gardiner-Garden Social Policy Section Contents Introduction ................................................................................................................................. 1 From Deakin to McMahon.......................................................................................................... 1 The Whitlam Government .......................................................................................................... 1 The establishing of the Australia Council ......................................................................... 2 Other initiatives ................................................................................................................. 3 The Fraser Government .............................................................................................................. 4 Initial policies .................................................................................................................... 4 Reviews and reports .......................................................................................................... 5 Other initiatives ................................................................................................................. 8 The Hawke Government ............................................................................................................ -

Constitutional Convention

CONSTITUTIONAL CONVENTION [2nd to 13th FEBRUARY 1998] TRANSCRIPT OF PROCEEDINGS Wednesday, 11 February 1998 Old Parliament House, Canberra INTERNET The Proof and Official Hansards of the Constitutional Convention are available on the Internet http://www.dpmc.gov.au/convention http://www.aph.gov.au/hansard RADIO BROADCASTS Broadcasts of proceedings of the Constitutional Convention can be heard on the following Parliamentary and News Network radio stations, in the areas identified. CANBERRA 1440 AM SYDNEY 630 AM NEWCASTLE 1458 AM BRISBANE 936 AM MELBOURNE 1026 AM ADELAIDE 972 AM PERTH 585 AM HOBART 729 AM DARWIN 102.5 FM INTERNET BROADCAST The Parliamentary and News Network has established an Internet site containing over 120 pages of information. Also it is streaming live its radio broadcast of the proceedings which may be heard anywhere in the world on the following address: http://www.abc.net.au/concon CONSTITUTIONAL CONVENTION Old Parliament House, Canberra 2nd to 13th February 1998 Chairman—The Rt Hon. Ian McCahon Sinclair MP The Deputy Chairman—The Hon. Barry Owen Jones AO, MP ELECTED DELEGATES New South Wales Mr Malcolm Turnbull (Australian Republican Movement) Mr Doug Sutherland AM (No Republic—ACM) Mr Ted Mack (Ted Mack) Ms Wendy Machin (Australian Republican Movement) Mrs Kerry Jones (No Republic—ACM) Mr Ed Haber (Ted Mack) The Hon Neville Wran AC QC (Australian Republican Movement) Cr Julian Leeser (No Republic—ACM) Ms Karin Sowada (Australian Republican Movement) Mr Peter Grogan (Australian Republican Movement) Ms Jennie George -

The Early Fraser Ministry

Chapter 3 The Early Fraser Ministry James Killen, Minister for Defence Before retirement in 1979 I served my remaining four years in government service under James Killen as Minister and Malcolm Fraser as Prime Minister. At the end there was a well-intentioned, but publicly controversial and financially impractical, proposal from Ministers that I accept an extension beyond the compulsory retiring age of 65, which I declined. On retirement, I was able to turn to neglected family affairs, some writing and occasional involvement in seminars, and to take a short-term appointment nominated by the Prime Minister to review the Public Service in Fiji for that Government. Killen had held the Navy portfolio (now defunct) in the McMahon Ministry. After the now familiar formalities of inducting a new Minister into some classified areas which were subject to limited access, my first interest was to ascertain whether the reorganised system, and the policies put in place by his Labor predecessor, would be confirmed or wound back. Several matters hung in the air. Although amendments to the Defence Act had been proclaimed, they were not to come into effect until February 1976. The content of the Five Year programme would need to be reviewed by the Government, along with its underlying strategic assumptions. We could expect a call for a comprehensive review of those assumptions. Recommendations expected from the Hope Royal Commission affecting Defence would require decision. There was the Defence Force Academy project, several times deferred. There were inefficiencies, such as the low productivity of the civilian workforce in the Williamstown Dockyard managed by the Navy, which needed fixing. -

Dancing with the Bear: the Politics of Australian National Cultural Policy

Dancing with the bear: the politics of Australian national cultural policy A thesis submitted to fulfil requirements for a degree of Doctor of Social Science Deborah Mills Faculty of Arts and Social Sciences The University of Sydney 2020 1 Statement of originality This is to certify that, to the best of my knowledge the content of this thesis is my own work. This thesis has not been submitted for any degree or other purposes. I certify that the intellectual content of this thesis is the product of my own work and that all the assistance received in preparing this thesis and sources have been acknowledged. Deborah Mills 2 Table of Contents Table of Figures 8 Table of Appendices 10 Abstract 12 Acknowledgements 13 Preface 14 Chapter One: Introduction 16 “Art in a Cold Climate” 16 Introducing the case studies 18 The limits of my inquiry 18 Bringing two theoretical frames together 19 Thesis structure: key themes and chapter outlines 22 Chapter Two: theory and method 27 Part One: public policy theory 27 What is public policy? 27 The Advocacy Coalition Framework 28 Neo-liberalism, culture, and governance 30 Part Two: critical cultural studies 32 Cultural studies and cultural policy 34 Is it art or cultural policy? 38 Art as excellence: its genius and distinctiveness 40 Art as industry: challenging excellence/confirming culture’s 42 exchange value De-colonising culture: access and excellence as cultural self 44 determination Part Three: cultural citizenship and arts policy modes 46 Cultural citizenship 46 Arts policy modes 47 Part Four: research -

Constitutional Convention

CONSTITUTIONAL CONVENTION [2nd to 13th FEBRUARY 1998] TRANSCRIPT OF PROCEEDINGS Monday, 9 February 1998 Old Parliament House, Canberra INTERNET The Proof and Official Hansards of the Constitutional Convention are available on the Internet http://www.dpmc.gov.au/convention http://www.aph.gov.au/hansard RADIO BROADCASTS Broadcasts of proceedings of the Constitutional Convention can be heard on the following Parliamentary and News Network radio stations, in the areas identified. CANBERRA 1440 AM SYDNEY 630 AM NEWCASTLE 1458 AM BRISBANE 936 AM MELBOURNE 1026 AM ADELAIDE 972 AM PERTH 585 AM HOBART 729 AM DARWIN 102.5 FM INTERNET BROADCAST The Parliamentary and News Network has established an Internet site containing over 120 pages of information. Also it is streaming live its radio broadcast of the proceedings which may be heard anywhere in the world on the following address: http://www.abc.net.au/concon CONSTITUTIONAL CONVENTION Old Parliament House, Canberra 2nd to 13th February 1998 Chairman—The Rt Hon. Ian McCahon Sinclair MP The Deputy Chairman—The Hon. Barry Owen Jones AO, MP ELECTED DELEGATES New South Wales Mr Malcolm Turnbull (Australian Republican Movement) Mr Doug Sutherland AM (No Republic—ACM) Mr Ted Mack (Ted Mack) Ms Wendy Machin (Australian Republican Movement) Mrs Kerry Jones (No Republic—ACM) Mr Ed Haber (Ted Mack) The Hon Neville Wran AC QC (Australian Republican Movement) Cr Julian Leeser (No Republic—ACM) Ms Karin Sowada (Australian Republican Movement) Mr Peter Grogan (Australian Republican Movement) Ms Jennie George (Australian -

'On the Edge of Asia': Australian Grand Strategy and the English-Speaking Alliance

‘On the edge of Asia’: Australian Grand Strategy and the English-Speaking Alliance, 1967-1980 A dissertation presented to the faculty of the College of Arts and Sciences of Ohio University In partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree Doctor of Philosophy Laura M. Seddelmeyer August 2014 © 2014 Laura M. Seddelmeyer. All Rights Reserved. 2 This dissertation titled ‘On the edge of Asia’: Australian Grand Strategy and the English-Speaking Alliance, 1967-1980 by LAURA M. SEDDELMEYER has been approved for the Department of History and the College of Arts and Sciences by Peter John Brobst Associate Professor of History Robert Frank Dean, College of Arts and Sciences 3 ABSTRACT SEDDELMEYER, LAURA M., Ph.D., August 2014, History 'On the edge of Asia': Australian Grand Strategy and the English-Speaking Alliance, 1967-1980 Director of Dissertation: Peter John Brobst This dissertation examines the importance of geopolitics in developing an Australian strategy during a transitional, but critical, period in Australian history, and it questions what effect the changing global environment had on the informal English- speaking alliance during the late Cold War. During the late 1960s, the effects of British decolonization, Southeast Asian nationalism, and American foreign policy changes created a situation on Australia’s doorstep, which the government in Canberra could not ignore. After World War II, strategic planning in Canberra emphasized the importance of British and American presence in the Asia-Pacific region to ensure Australian security. The postwar economic challenges facing Great Britain contributed to the decision in July 1967 to withdraw forces from ‘east of Suez’ by the mid-1970s. -

Menzies, Whitlam, and Social Justice: a View from the Academy Sir Robert Menzies Oration on Higher Education University of Melbourne

Menzies, Whitlam, and Social Justice: A View from The Academy Sir Robert Menzies Oration on Higher Education University of Melbourne 23 October 2012 Professor Janice Reid1 AM 1 Vice-Chancellor, University of Western Sydney Chancellor, Vice-Chancellor, distinguished guests. To be invited to give this oration is a great honour and I thank the University and the Board for this privilege. I begin by acknowledging the Wurundjeri people of the Kulin nation, the traditional owners of the land on which this oration and ceremony are being held. I also acknowledge all Aboriginal people here today, and the ancestors who cared for this land for countless millennia. Comment has been made on my professional longevity – 14 years in my current role. I’m not sure that the accretion of years is especially noteworthy but it did bring to mind Gough Whitlam who, when in his mid-80s, as guest speaker at a commemorative event in western Sydney said by way of introduction, “I expect you’re all rather surprised to see me here today”. A long pause. “You probably expected me to have been taken up by now”. He gazed at his bemused audience and continued, “Frankly, I think the Almighty doesn’t want the competition”. With masterful timing he waited until the mirth had subsided and added ponderously, “Personally I’d have thought He’d enjoy the conversation”. The Commanding Heights I should declare that the title of my talk today, Menzies, Whitlam, and Social Justice is respectfully appropriated from the 1999 Sir Robert Menzies Lecture by Petro Georgiou, entitled Menzies, Liberalism and Social Justice. -

VOTES and PROCEEDINGS No

1980-81-82 1059 THE PARLIAMENT OF THE COMMONWEALTH OF AUSTRALIA HOUSE OF REPRESENTATIVES VOTES AND PROCEEDINGS No. 105 TUESDAY, 21 SEPTEMBER 1982 1 The House met, at 1.45 p.m., pursuant to adjournment. Mr Speaker (the Right Honourable Sir Billy Snedden) took the Chair, and read Prayers. 2 AUSTRALIAN MEAT INDUSTRY-REPORT OF ROYAL COMMISSION-PAPERS AND MINISTERIAL STATEMENT-MOTION TO TAKE NOTE OF PAPERS: Mr Fraser (Prime Minister), by command of His Excellency the Governor-General, presented the following paper: Australian Meat Industry-Report of Royal Commission, dated September 1982. Suspension of standing orders-Ministerial statement: Sir James Killen (Leader of the House) moved-That so much of the standing orders be suspended as would prevent Mr Fraser making a statement to the House forthwith. Debate ensued. Question-put and passed, with the concurrence of an absolute majority. Mr Fraser made a ministerial statement in connection with the report, and, by command of His Excellency the Governor-General, presented the following papers: Australian Meat Industry-Royal Commission- Extract from transcript of evidence of 13-14 July 1982 (pp. 10240-10342). Ministerial statement, 21 September 1982. Record of telephone conversation between Mr W. A. Buettel, member of the committee of inquiry to examine Commonwealth and State meat inspection systems, and Mr L. P. Duthie, Secretary, Department of Primary Industry, dated 19 September 1982. Sir James Killen moved-That the House take note of the papers. Suspension of standing orders-Extended timefor speech: Sir James Killen, by leave, moved-That so much of the standing orders be suspended as would prevent Mr Hayden (Leader of the Opposition) speaking for a period not exceeding 62 minutes.