The Early Fraser Ministry

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Removal of Whitlam

MAKING A DEMOCRACY to run things, any member could turn up to its meetings to listen and speak. Of course all members cannot participate equally in an org- anisation, and organisations do need leaders. The hopes of these reformers could not be realised. But from these times survives the idea that any governing body should consult with the people affected by its decisions. Local councils and governments do this regularly—and not just because they think it right. If they don’t consult, they may find a demonstration with banners and TV cameras outside their doors. The opponents of democracy used to say that interests had to be represented in government, not mere numbers of people. Democrats opposed this view, but modern democracies have to some extent returned to it. When making decisions, governments consult all those who have an interest in the matter—the stake- holders, as they are called. The danger in this approach is that the general interest of the citizens might be ignored. The removal of Whitlam The Labor Party captured the mood of the 1960s in its election campaign of 1972, with its slogan ‘It’s Time’. The Liberals had been in power for 23 years, and Gough Whitlam said it was time for a change, time for a fresh beginning, time to do things differently. Whitlam’s government was in tune with the times because it was committed to protecting human rights, to setting up an ombuds- man and to running an open government where there would be freedom of information. But in one thing Whitlam was old- fashioned: he believed in the original Labor idea of democracy. -

Howard Government Retrospective II

Howard Government Retrospective II “To the brink: 1997 - 2001” Articles by Professor Tom Frame 14 - 15 November 2017 Howard Government Retrospective II The First and Second Howard Governments Initial appraisals and assessments Professor Tom Frame Introduction I have reviewed two contemporaneous treatments Preamble of the first Howard Government. Unlike other Members of the Coalition parties frequently complain retrospectives, these two works focussed entirely on that academics and journalists write more books about the years 1996-1998. One was published in 1997 the Australian Labor Party (ALP) than about Liberal- and marked the first anniversary of the Coalition’s National governments and their leaders. For instance, election victory. The other was published in early three biographical studies had been written about Mark 2000 when the consequences of some first term Latham who was the Opposition leader for a mere decisions and policies were becoming a little clearer. fourteen months (December 2003 to February 2005) Both books are collections of essays that originated when only one book had appeared about John Howard in university faculties and concentrated on questions and he had been prime minister for nearly a decade. of public administration. The contributions to both Certainly, publishers believe that books about the Labor volumes are notable for the consistency of their tone Party (past and present) are usually more successful and tenor. They are not partisan works although there commercially than works on the Coalition parties. The is more than a hint of suspicion that the Coalition sales figures would seem to suggest that history and was tampering with the institutions that undergirded ideas mean more to some Labor followers than to public authority and democratic government in Coalition supporters or to Australian readers generally. -

THE 'RAZOR GANG' Decisions, the GUIDELINES to THE

THE 'RAZOR GANG' DECISiONS, Granl Harman In this paper, I discuss the political-administrative A third consideration is that the Prime Minister's Centre for the Study of Higher Education, context in which the Government's decisions were leadership is by no means secure in the long term. THE GUIDELINES University 01 Melbourne made, summarize the main decisions with regard to One possible partial explanation for the decisions is TO THE COMMISSIONS, education, and comment on the significance and that the Prime Minister needed to demonstrate in a possible consequences with regard to four topics: relatively dramatic fashion his ability and wiUingness AND COMMONWEALTH the future of Commonwealth involvement in educa to be a leader of action, and to take tough decisions. tion; funding for tertiary education; the introduction of Significantly the 'Razor Gang' decisions affect all EDUCATION POLICY tuition fees in universities and CAEs; and the rational portfolios, but in cases such as the Department of ization of single-purpose teacher education CAEs. Prime Minister and Cabinet the 'cuts' appear to be largely cosmetic. Political~Administrative Context Introduction has there been such a sudden and extensive planned In terms of the general political context with regard to Fourth, for various reasons education generally no In recent months the Commonwealth Government cut in government programs, and such a sweeping the two sets of decisions, four points should be kept longer commands the same degree of support that it has announced two sets of important and far elimination of government committees and agencies. in mind. In the first place, it is clear that the Govern appeared to enjoy during the late 1960s. -

The Rhodesian Crisis in British and International Politics, 1964

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by University of Birmingham Research Archive, E-theses Repository THE RHODESIAN CRISIS IN BRITISH AND INTERNATIONAL POLITICS, 1964-1965 by CARL PETER WATTS A thesis submitted to the University of Birmingham For the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY School of Historical Studies The University of Birmingham April 2006 University of Birmingham Research Archive e-theses repository This unpublished thesis/dissertation is copyright of the author and/or third parties. The intellectual property rights of the author or third parties in respect of this work are as defined by The Copyright Designs and Patents Act 1988 or as modified by any successor legislation. Any use made of information contained in this thesis/dissertation must be in accordance with that legislation and must be properly acknowledged. Further distribution or reproduction in any format is prohibited without the permission of the copyright holder. Abstract This thesis uses evidence from British and international archives to examine the events leading up to Rhodesia’s Unilateral Declaration of Independence (UDI) on 11 November 1965 from the perspectives of Britain, the Old Commonwealth (Canada, Australia, and New Zealand), and the United States. Two underlying themes run throughout the thesis. First, it argues that although the problem of Rhodesian independence was highly complex, a UDI was by no means inevitable. There were courses of action that were dismissed or remained under explored (especially in Britain, but also in the Old Commonwealth, and the United States), which could have been pursued further and may have prevented a UDI. -

22. Gender and the 2013 Election: the Abbott 'Mandate'

22. Gender and the 2013 Election: The Abbott ‘mandate’ Kirsty McLaren and Marian Sawer In the 2013 federal election, Tony Abbott was again wooing women voters with his relatively generous paid parental leave scheme and the constant sight of his wife and daughters on the campaign trail. Like Julia Gillard in 2010, Kevin Rudd was assuring voters that he was not someone to make an issue of gender and he failed to produce a women’s policy. Despite these attempts to neutralise gender it continued to be an undercurrent in the election, in part because of the preceding replacement of Australia’s first woman prime minister and in part because of campaigning around the gender implications of an Abbott victory. To evaluate the role of gender in the 2013 election, we draw together evidence on the campaign, campaign policies, the participation of women, the discursive positioning of male leaders and unofficial gender-based campaigning. We also apply a new international model of the dimensions of male dominance in the old democracies and the stages through which such dominance is overcome. We argue that, though feminist campaigning was a feature of the campaign, traditional views on gender remain powerful. Raising issues of gender equality, as Julia Gillard did in the latter part of her prime ministership, is perceived as electorally damaging, particularly among blue-collar voters. The prelude to the election Gender received most attention in the run-up to the election in 2012–13 rather than during the campaign itself. Prime Minister Julia Gillard’s famous misogyny speech of 2012 was prompted in immediate terms by the Leader of the Opposition drawing attention to sexism in what she perceived as a hypocritical way. -

William Mcmahon: the First Treasurer with an Economics Degree

William McMahon: the first Treasurer with an economics degree John Hawkins1 William McMahon was Australia’s first treasurer formally trained in economics. He brought extraordinary energy to the role. The economy performed strongly during McMahon’s tenure, although there are no major reforms to his name, and arguably pressures were allowed to build which led to the subsequent inflation of the 1970s. Never popular with his cabinet colleagues, McMahon’s public reputation was tarnished by his subsequent unsuccessful period as prime minister. Source: National Library of Australia.2 1 The author formerly worked in the Domestic Economy Division, the Australian Treasury. This article has benefited from comments provided by Selwyn Cornish and Ian Hancock but responsibility lies with the author and the views are not necessarily those of Treasury. 83 William McMahon: the first treasurer with an economics degree Introduction Sir William McMahon is now recalled by the public, if at all, for accompanying his glamorous wife to the White House in a daringly revealing outfit (hers not his). Comparisons invariably place him as one of the weakest of the Australian prime ministers.3 Indeed, McMahon himself recalled it as ‘a time of total unpleasantness’.4 His reputation as treasurer is much better, being called ‘by common consent a remarkably good one’.5 The economy performed well during his tenure, but with the global economy strong and no major shocks, this was probably more good luck than good management.6 His 21 years and four months as a government minister, across a range of portfolios, was the third longest (and longest continuously serving) in Australian history.7 In his younger days he was something of a renaissance man; ‘a champion ballroom dancer, an amateur boxer and a good squash player — all of which require, like politics, being fast on his feet’.8 He suffered deafness until it was partly cured by some 2 ‘Portrait of William McMahon, Prime Minister of Australia from 1971-1972/Australian Information Service’, Bib ID: 2547524. -

Report on Economic and Finance Institute of Cambodia

THE HONOURABLE JOHN WINSTON HOWARD OM AC Citation for the conferral of Doctor of the University (honoris causa) Chancellor, it is a privilege to present to you and to this gathering, for the award of Doctor of the University (honoris causa), the Honourable John Winston Howard OM AC. The Honourable John Howard is an Australian politician who served as the 25th Prime Minister of Australia from 11 March 1996 to 3 December 2007. He is the second-longest serving Australian Prime Minister after Sir Robert Menzies. Mr Howard was a member of the House of Representatives from 1974 to 2007, representing the Division of Bennelong, New South Wales. He served as Treasurer in the Fraser government from 1977 to 1983 and was Leader of the Liberal Party and Coalition Opposition from 1985 to 1989, which included the 1987 federal election against Bob Hawke. Mr Howard was re-elected as Leader of the Opposition in 1995. He led the Liberal- National coalition to victory at the 1996 federal election, defeating Paul Keating's Labor government and ending a record 13 years of Coalition opposition. The Howard Government was re-elected at the 1998, 2001 and 2004 elections, presiding over a period of strong economic growth and prosperity. During his term as Prime Minister, Mr Howard was a supporter of Charles Sturt University and its work in addressing the needs of rural communities. Mr Howard was integral to the development of local solutions to address the chronic shortage of dentists and oral health professionals in rural and regional Australia. During his term, Mr Howard was a proponent for the establishment of dental schools in rural and regional Australia including at Charles Sturt University in Orange and Wagga Wagga and La Trobe University in Bendigo. -

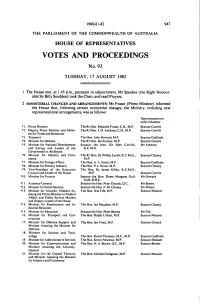

Votes and Proceedings

1980-81-82 947 THE PARLIAMENT OF THE COMMONWEALTH OF AUSTRALIA HOUSE OF REPRESENTATIVES VOTES AND PROCEEDINGS No. 93 TUESDAY, 17 AUGUST 1982 1 The House met, at 1.45 p.m., pursuant to adjournment. Mr Speaker (the Right Honour- able Sir Billy Snedden) took the Chair, and read Prayers. 2 MINISTERIAL CHANGES AND ARRANGEMENTS: Mr Fraser (Prime Minister) informed the House that, following certain ministerial changes, the Ministry, including new representational arrangements, was as follows: Representationin other Chamber *1. Prime Minister The Rt Hon. Malcolm Fraser, C.H., M.P. Senator Carrick *2. Deputy Prime Minister and Minis- The Rt Hon. J. D. Anthony, C.H., M.P. Senator Carrick ter for Trade and Resources *3. Treasurer The Hon. John Howard, M.P. Senator Guilfoyle *4. Minister for Defence The Rt Hon. lan Sinclair, M.P. Senator Durack *5. Minister for National Development Senator the Hon. Sir John Carrick, Mr Anthony and Energy and Leader of the K.C.M.G. Government in the Senate *6. Minister for Industry and Com- The Rt Hon. Sir Phillip Lynch, K.C.M.G., Senator Chaney merce M.P. *7. Minister for Foreign Affairs The Hon. A. A. Street, M.P. Senator Guilfoyle *8. Minister for Primary Industry The Hon. P. J. Nixon, M.P. Senator Chancy *9. Vice-President of the Executive The Hon. Sir James Killen, K.C.M.G., Council and Leader of the House M.P. Senator Carrick *10. Minister for Finance Senator the Hon. Dame Margaret Guil- Mr Howard foyle, D.B.E. *11. Attorney-General Senator the Hon. -

Gough Whitlam, a Moment in History

Gough Whitlam, A Moment in History By Jenny Hocking: The Miegunyah Press, Mup, Carlton Victoria, 2008, 9780522111 Elaine Thompson * Jenny Hocking is, as the media release on this book states, an acclaimed and accomplished biographer and this book does not disappoint. It is well written and well researched. My only real complaint is that it should be clearer in the title that it only concerns half of Gough Whitlam’s life, from birth to accession the moment of the 1972 election. It is not about Whitlam as prime minister or the rest of his life. While there are many books about Whitlam’s term as prime minister, I hope that Jenny Hocking will make this book one of a matched pair, take us through the next period; and that Gough is still with us to see the second half of his life told with the interest and sensitivity that Jenny Hocking has brought to this first part. Given that this is a review in the Australasian Parliamentary Review it seems appropriate to concentrate a little of some of the parliamentary aspects of this wide ranging book. Before I do that I would like to pay my respects to the role Margaret Whitlam played in the story. Jenny Hocking handles Margaret’s story with a light, subtle touch and recognizes her vital part in Gough’s capacity to do all that he did. It is Margaret who raised the children and truly made their home; and then emerges as a fully independent woman and a full partner to Gough. The tenderness of their relationship is indicated by what I consider a lovely quote from Margaret about their first home after their marriage. -

Effective Protection and I

EFFECTIVE PROTECTION AND I Published in History of Economics Review, No 42. Summer 2005, pp. 1-11. Informed and detached biography is better than autobiography, which may be better informed but, inevitably, is less detached. This paper is an exercise in mini-autobiography, a little bit of history of thought1. I shall try to be detached, but perhaps it is best to say caveat emptor. So, readers, beware! I shall assume that the reader knows what “effective protection” is about. If not, the basic idea can be found in any textbook of international economics, and more fully in Corden (1966, 1971), and Greenaway and Milner (2003). In January 1958 I returned to Australia from London, and took up my first academic position, as Lecturer at the University of Melbourne. I had already written one article about the cost of protection, inspired by the Brigden Report on the Australian tariff (Brigden, et. al. 1929). My article was published in the Economic Record (Corden,1957). Australia still had comprehensive import licensing in 1958. This system, established in the balance-of- payments crisis of 1952, was ended in 1960, when tariffs became again the (almost) sole means of restriction of 1 I am indebted to Robert Dixon for suggesting that I embark on this somewhat egocentric exercise. I have also benefited from his comments on a draft. 1 imports2. At the June 1958 congress of Section G of ANZAAS (the predecessor of the annual conference of Australian economists) I presented a paper on “Import Restrictions and Tariffs: A New Look at Australian Policy”, in which I proposed replacing import restrictions with a uniform tariff. -

House of Representatives By-Elections 1902-2002

INFORMATION, ANALYSIS AND ADVICE FOR THE PARLIAMENT INFORMATION AND RESEARCH SERVICES Current Issues Brief No. 15 2002–03 House of Representatives By-elections 1901–2002 DEPARTMENT OF THE PARLIAMENTARY LIBRARY ISSN 1440-2009 Copyright Commonwealth of Australia 2003 Except to the extent of the uses permitted under the Copyright Act 1968, no part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means including information storage and retrieval systems, without the prior written consent of the Department of the Parliamentary Library, other than by Senators and Members of the Australian Parliament in the course of their official duties. This paper has been prepared for general distribution to Senators and Members of the Australian Parliament. While great care is taken to ensure that the paper is accurate and balanced, the paper is written using information publicly available at the time of production. The views expressed are those of the author and should not be attributed to the Information and Research Services (IRS). Advice on legislation or legal policy issues contained in this paper is provided for use in parliamentary debate and for related parliamentary purposes. This paper is not professional legal opinion. Readers are reminded that the paper is not an official parliamentary or Australian government document. IRS staff are available to discuss the paper's contents with Senators and Members and their staff but not with members of the public. Published by the Department of the Parliamentary Library, 2003 I NFORMATION AND R ESEARCH S ERVICES Current Issues Brief No. 15 2002–03 House of Representatives By-elections 1901–2002 Gerard Newman, Statistics Group Scott Bennett, Politics and Public Administration Group 3 March 2003 Acknowledgments The authors would like to acknowledge the assistance of Murray Goot, Martin Lumb, Geoff Winter, Jan Pearson, Janet Wilson and Diane Hynes in producing this paper. -

The Legacy of Robert Menzies in the Liberal Party of Australia

PASSING BY: THE LEGACY OF ROBERT MENZIES IN THE LIBERAL PARTY OF AUSTRALIA A study of John Gorton, Malcolm Fraser and John Howard Sophie Ellen Rose 2012 'A thesis submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of BA (Hons) in History, University of Sydney'. 1 Acknowledgements Firstly, I would like to acknowledge the guidance of my supervisor, Dr. James Curran. Your wisdom and insight into the issues I was considering in my thesis was invaluable. Thank you for your advice and support, not only in my honours’ year but also throughout the course of my degree. Your teaching and clear passion for Australian political history has inspired me to pursue a career in politics. Thank you to Nicholas Eckstein, the 2012 history honours coordinator. Your remarkable empathy, understanding and good advice throughout the year was very much appreciated. I would also like to acknowledge the library staff at the National Library of Australia in Canberra, who enthusiastically and tirelessly assisted me in my collection of sources. Thank you for finding so many boxes for me on such short notice. Thank you to the Aspinall Family for welcoming me into your home and supporting me in the final stages of my thesis and to my housemates, Meg MacCallum and Emma Thompson. Thank you to my family and my friends at church. Thank you also to Daniel Ward for your unwavering support and for bearing with me through the challenging times. Finally, thanks be to God for sustaining me through a year in which I faced many difficulties and for providing me with the support that I needed.