95Th EAAE Seminar Civitavecchia (Rome), 9-11 December 2005

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

CV Antonella Saletti Dicembre 2017.Pdf

Arch. Antonella SalettiI Via Gorgognano , 420 Certaldo (FI) CURRICULUM FORMATIVO PROFESSIONALE Dichiarazione sostitutiva ai sensi del D.P.R. 445/28.12.2000 La sottoscritta Antonella Saletti, nata a Castel del Piano (GR) il 13/06/69, residente a Certaldo, via Gorgonano, 420 consapevole delle responsabilità penali cui può andare incontro in caso di dichiarazioni mendaci, ai sensi e per gli effetti di cui all’art. 76 del D.P.R. 445/2000 e sotto la propria responsabilità, dichiara: DATI PERSONALI Nome e cognome Antonella Saletti Luogo e data nascita Castel del Piano (GR) 13/06/69 Residenza Via Gorgonano, 420, Certaldo (FI) Domicilio Via Gorgonano, 420, Certaldo (FI) Recapiti Cell 338/3715980 333/7501758 e-mail [email protected] [email protected] Professione Iscritta all’Ordine degli Architetti, Pianificatori, Paesaggisti e Conservatori di Firenze, settore A, il 22/12/2004, con il numero 6573 P. IVA / c. fiscale 05392800487 / SLTNNL69H53C085C FORMAZIONE novembre 2002 Laurea in Architettura, votazione 108/110, presso l’Università degli Studi di Firenze, Facoltà di Architettura, indirizzo urbanistico, tesi di laurea “Crete senesi: territorio e architettura”, relatore Prof. Gianfranco Di Pietro ottobre 2014 Corso di formazione professionale “Il Restauro tra conservazione, sicurezza, riuso”. Cortona 17-18 Ottobre 2014. Organizzatori: Federazione Architetti, Pianificatori, Paesaggisti, conservatori Toscani, Ordine degli Architetti di Siena, Scuola Permanente dell’Abitare. ottobre 1996-giugno Collaborazione al corso di Pianificazione Ambientale tenuto dal Prof. Riccardo Foresi 1998 presso il Dipartimento di Urbanistica e Pianificazione del Territorio, Facoltà di Architettura di Firenze. 1996-1997 Partecipazione presso il Dipartimento di Urbanistica e Pianificazione del Territorio, Facoltà di Architettura di Firenze alla ricerca “Ambiente, paesaggio e sistemi insediativi del territorio toscano: un patrimonio a rischio. -

1 Bando Di Gara

Monte Argentario Capalbio Magliano in Toscana CENTRALE UNICA DI COMMITTENZA tra i Comuni di: Monte Argentario – Capalbio – Magliano in Toscana C.U.C. - MAREMMA 1 Sede: Comune di Monte Argentario – P.le dei Rioni n. 8 Porto S. Stefano tel. 0564-811934 – e-mail: [email protected] pec: [email protected] BANDO DI GARA MEDIANTE PROCEDURA NEGOZIATA Procedura di aggiudicazione: procedura negoziata art. 36 c. 2 lett. b) D.Lgs n. 50/2016 Criterio di aggiudicazione: “minor prezzo” ex art. 95 c. 4 del D.Lgs. 50/2016 Appalto per affidamento della gestione dei servizi dei cimiteri comunali di Porto S. Stefano e di Porto Ercole in Monte Argentario – anno 2019- 2020 - CIG: 78313087CC SEZIONE I: AMMINISTRAZIONE AGGIUDICATRICE I.1) Denominazione, indirizzi e punti di contatto Denominazione ufficiale: COMUNE DI MONTE ARGENTARIO (GR) Indirizzo postale: Piazzale dei Rioni, 8 Città: Porto S. Stefano CAP 58019 Paese: Italia Punti di contatto: Centralino Telefono + 390564/811911 Arch. Marco Pareti Telefono + 390564/811934 posta elettronica: [email protected] [email protected] Sito internet: http://www.comunemonteargentario.gov.it Ulteriori informazioni, il progetto e la documentazione di gara è disponibile presso il punto di contatto sopraindicato. I.2) L’appalto è aggiudicato dal Comune di Monte Argentario. I.3) I documenti di gara sono disponibili per un accesso gratuito, illimitato e diretto presso il link: http://www.comunemonteargentario.gov.it/uffici-e-servizi/cuc-centrale-unica-di-committenza.html Ulteriori informazioni, il progetto e la documentazione di gara è disponibile presso il punto di contatto sopraindicato (Ufficio Gare e C.U.C. -

25. Colline Dell'albegna

Sistemi territoriali del PIT: Toscana delle Aree interne e meridionali Toscana della Costa e dell’Arcipelago C O L L I N E D E L L‘ A L B E G N A Provincia: Grosseto Territori appartenenti ai Comuni: Castell’Azzara, Magliano in Toscana, Manciano, Roccalbegna, Scansano, Semproniano Superficie dell’ambito: circa 120000 ettari Campi chiusi Oliveti specializzati a seminativo semplice Versanti con boschi Affioramenti calcarei Insediamenti sulle pendici basse a prevalenza di latifoglie da cui nasce il fiume Nucleo storico di origine recenti Albegna medievale (Roccalbegna) confine regionale Formazioni forestali confine regionale Colture agrarie miste L’ambito è caratterizzato morfologicamente dal dell’Albegna, il biotopo di Santissima Trinità e la crinale che dal Monte Labbro scende verso la Riserva Naturale di Pescinello e Rocconi. Prati e pascoli costa, comprendendo anche una piccola La media valle dell’Albegna presenta pendici più alternati porzione dei Monti dell’Uccellina, dove sono dolci dove alle aree boscate si sostituiscono le ad aree boscate concentrati i centri storici maggiori (Roccalbegna, coltivazioni, prevalentemente a oliveto e vigneto Scansano e Magliano), e dalle colline del fiume nelle parti più ondulate, mentre sulle aree più Boschi misti Corso d’acqua Albegna. pianeggianti prevalgono i seminativi. confine di latifoglie con vegetazione I versanti dell’alta valle dell’Albegna sono di regionale Vigneti Alla significativa presenza delle colture di ripa natura rocciosa, morfologicamente aspri e ripidi. Oliveti specializzati specializzate risulta associata una consistente In prossimità di Murci-Poggioferro si incontrano con siepi dotazione di filari, siepi e macchie boscate, che formazioni arenarie quarzoso-feldspatiche e Colture agrarie specializzate e macchie di conferisce una specifica fisionomia al paesaggio. -

Porto Ercole

040-081_Cap2.1_100408++.qxd:148x210 mm 08.04.2010 17:16 Uhr Seite 40 2 capitolo Il Monte Argentario nella prima metà del XVI secolo I confini tra le comunità di Porto Ercole e Orbetello — 42 Andrea Doria conquista Porto Ercole — 52 Gli interventi alla Rocca e alla Casamatta di Porto Ercole — 68 Portercolesi contro tutti — 82 Bartolomeo Peretti da Talamone — 87 Gli Spagnoli a Porto Ercole — 89 La devastante incursione del corsaro Barbarossa — 100 Il porto di Santo Stefano — 111 I progetti per una città ideale all’Argentario — 121 Cronologia: Le fasi salienti della guerra di Siena — 133 40 — La presa di Porto Ercole 2 capitolo: Il Monte Argentario nella prima metà del ’500 — 41 040-081_Cap2.1_100408++.qxd:148x210 mm 08.04.2010 17:16 Uhr Seite 42 Il Monte Argentario nella prima metà del ‘500 suoi. Nel 1495, mentre il fratello Giacomo entrava a far parte del I confini tra le comunità triumvirato che in pratica reggeva il governo della città, Pandolfo fu proposto al comando delle Trecento guardie del Palazzo, che di Porto Ercole e Orbetello costituivano il piccolo esercito permanente di Siena. Dopo varie vicissitudini, che lo videro persino abbandonare la città in segno di sdegno verso i suoi concittadini, Pandolfo Petrucci fu eletto a storia di Siena è contraddistinta da un continuo membro del Collegio di Balia e, dopo la morte del fratello Gia - succedersi di lotte intestine e soltanto la capacità dei como (1497), divenne il personaggio più in vista dello Senesi di ritrovare concordia e unione nei momenti Stato Senese. di maggior pericolo evitò alla gloriosa e antica Repub - Nel tentativo di mantenere e consolidare il Lblica di perdere anzitempo l’indipendenza. -

Lega Nazionale Dilettanti * Toscana

* COMITATO * F. I. G. C. - LEGA NAZIONALE DILETTANTI * TOSCANA * ************************************************************************ * * * SECONDA CATEGORIA GIRONE: G * * * ************************************************************************ .--------------------------------------------------------------. .--------------------------------------------------------------. .--------------------------------------------------------------. | ANDATA: 18/09/16 | | RITORNO: 15/01/17 | | ANDATA: 23/10/16 | | RITORNO: 19/02/17 | | ANDATA: 27/11/16 | | RITORNO: 26/03/17 | | ORE...: 15:30 | 1 G I O R N A T A | ORE....: 14:30 | | ORE...: 15:30 | 6 G I O R N A T A | ORE....: 15:00 | | ORE...: 14:30 | 11 G I O R N A T A | ORE....: 15:30 | |--------------------------------------------------------------| |--------------------------------------------------------------| |--------------------------------------------------------------| | CINIGIANO - SAURORISPESCIA DILETTANT. | | CINIGIANO - INTERCOMUNALE S.FIORA | | ALDOBRANDESCA ARCIDOSSO - SORANO A.S.D. | | INTERCOMUNALE S.FIORA - INVICTA GR CALCIO GIOVANI | | INVICTA GR CALCIO GIOVANI - MAGLIANESE | | INVICTA GR CALCIO GIOVANI - NUOVA RADICOFANI | | LA SORBA CASCIANO - PUNTA ALA 2013 | | NUOVA RADICOFANI - LA SORBA CASCIANO | | LA SORBA CASCIANO - SAURORISPESCIA DILETTANT. | | MAGLIANESE - ALDOBRANDESCA ARCIDOSSO | | PUNTA ALA 2013 - PIENZA | | MAGLIANESE - PORTO ERCOLE | | MARSILIANA AICS - PIENZA | | S.ANDREA - PORTO ERCOLE | | MARSILIANA AICS - INTERCOMUNALE S.FIORA | | ORBETELLO A.S.D. - NUOVA -

La Ripresa Delle Indagini a Giglio Porto

BOLLETTINO DI ARCHEOLOGIA ON LINE DIREZIONE GENERALE ARCHEOLOGIA, BELLE ARTI E PAESAGGIO X, 2019/3-4 JACOPO TABOLLI*, MATTEO COLOMBINI**, GIUSEPPINA GRIMAUDO***, con il contributo di PAOLO NANNINI*, FLAVIA LODOVICI**** e FRANCESCA GIAMBRUNI**** SBARCANDO AL GIGLIO (GR). LA RIPRESA DELLE INDAGINI ARCHEOLOGICHE A GIGLIO PORTO A TERRA E IN MARE This paper presents the results of the 2018 excavations at Giglio Porto, in the Roman harbour of Isola del Giglio. Archaeological surveillance during the construction of a small parking lot in the area of Saraceno brought to light a previously unknown part of the Roman villa and especially two sets of corner walls in opus reticulatum with remains of decoration with painted plaster. Vaulted substructures also appeared thus allowing us to identify this area as an intermediate space between the upper terrace of the villa and the lower sector, where the monumental northern semicircular terrace is located, overlooking the bay. At the same time, inside the modern harbour new remains of the Roman one came to light during underwater archaeological survey in the western part of the harbour. A granite bollard, probably connected to one of the ancient piers, has been uncovered together with the remains of architectural elements among which a series of only partially worked granite columns stand out. The concentration of these remains may be connected to the quarry of the Foriano (or Forano), located on top of the Roman Harbour which probably used the small Vado di San Giorgio (the main water stream of the area) as a way downhill towards the harbour and from there the cargos towards Giannutri or the mainland. -

Pubblicita' Ed Affissioni

COMUNE DI CAPALBIO (Provincia di Grosseto) Via G.Puccini,32 58011 Capalbio (GR) Tel . 0564897701 Fax 0564 897744 www.comune.capalbio.gr.it e-mail [email protected] STORIA DI CAPALBIO I Non si puo’ parlare della storia di Capalbio senza accennare al castello piu’ antico di Tricosto (oggi detto Capalbiaccio) di cui sono le rovine sul colle sito a Nord Ovest a due km dall’incrocio sulla S.S.Aurelia con accesso a Capalbio Scalo. Dall’alto del poggio e’ possibile abbracciare con un solo sguardo la Valle d’Oro. Esso ha all’incirca la forma di un triangolo, la cui base è rappresentata dai terreni impaludati che formano il prolungamento del lago di Burano verso Ansedonia, mentre i lati – piu’ o meno irregolari – sono costituiti da una serie di dolci rilievi collinosi che trovano il loro vertice in direzione del Monte Alzato. La Valle e’ oggi, e doveva essere anche in antico la pianura piu’ fertile dell’immediato retroterra della collina di Ansedonia. Allorquando (nel 273 a. C.) i romani fondarono su quella collina la colonia latina di Cosa, la Valle d’Oro entro’ a far parte del territorio della nuova citta’ e dovette essere divisa in piccoli lotti (probabilmente di un ettaro e mezzo di media) fra i primi coloni. L’indagine archeologica – tutt’ora in corso – ha rilevato tracce di insediamento deferibili al sistema di piccole fattorie unifamiliari che caratterizzo’ la proprieta’ e l’economia agricola del territorio per alcune generazioni fino a una data ancora imprecisata – ma da collocare certamente fra il II e la prima meta’ del I sec. -

Guarda Il PDF: Orari, Fermate E Percorso Linea

Orari e mappe della linea bus 20A 20A Arcidosso-Santa Fiora-Castell'Azzara Visualizza In Una Pagina Web La linea bus 20A (Arcidosso-Santa Fiora-Castell'Azzara) ha 12 percorsi. Durante la settimana è operativa: (1) Amiata Stazione: 13:25 (2) Arcidosso Autostazione: 06:10 - 15:30 (3) Arcidosso Autostazione: 05:20 - 19:15 (4) Castel Del Piano Centrale: 07:10 - 18:00 (5) Castell'Azzara Centro: 08:05 - 19:29 (6) Largo Verdi: 05:46 - 06:40 (7) Piancastagnaio Centro: 06:10 (8) Santa Fiora Centrale: 14:30 - 15:50 (9) Seggiano C.Le: 05:50 - 15:05 (10) Seggiano Comune: 19:00 (11) Selvena Centro: 14:30 Usa Moovit per trovare le fermate della linea bus 20A più vicine a te e scoprire quando passerà il prossimo mezzo della linea bus 20A Direzione: Amiata Stazione Orari della linea bus 20A 34 fermate Orari di partenza verso Amiata Stazione: VISUALIZZA GLI ORARI DELLA LINEA lunedì 13:25 martedì 13:25 Arcidosso Autostazione mercoledì 13:25 Arcidosso Centrale giovedì 13:25 Arcidosso Cimitero venerdì 13:25 Arcidosso Ponti sabato 13:25 Montoto domenica Non in servizio Arcidosso S.Lorenzo Castel Del Piano Campeggio Informazioni sulla linea bus 20A Castel Del Piano Hotel Impero Direzione: Amiata Stazione Fermate: 34 Durata del tragitto: 47 min Castel Del Piano Vittorio Veneto La linea in sintesi: Arcidosso Autostazione, Via Dalmazia, Castel del Piano Arcidosso Centrale, Arcidosso Cimitero, Arcidosso Ponti, Montoto, Arcidosso S.Lorenzo, Castel Del Castel Del Piano Centrale Piano Campeggio, Castel Del Piano Hotel Impero, Castel Del Piano Vittorio Veneto, Castel Del Piano Castel Del Piano Ospedale Centrale, Castel Del Piano Ospedale, Castel Del Piano Santucci, Castel Del Piano Santucci, Castel Del Piano Castel Del Piano Santucci Cimitero, Castel Del Piano Bivio Casella, Leccio, Pescina Bivio Sud, Pian Di Ballo, Tepolini, Podere La Castel Del Piano Santucci Lama, Bv. -

Week and in Toscana in E-Bike Monte Argentario - Laguna Di Orbetello - Lago Di Burano

WEEK AND IN TOSCANA IN E-BIKE MONTE ARGENTARIO - LAGUNA DI ORBETELLO - LAGO DI BURANO Su due ruote, alla scoperta del Monte Argentario, della laguna di Orbetello e della meravigliosa oasi WWF del lago di Burano, un mix di natura, panorami mozzafiato sulle isole dell’Arcipelago Toscano, storia e sapori di una volta. (circa 80 km, 3 giorni / 2 notti; viaggio individuale o di gruppo) DESCRIZIONE: Un fine settimana di mare, ma non le classiche spiagge affollate di turisti, ma scogliere a picco sul mare, la laguna di Orbetello, il Tombolo della Feniglia ed infine il Lago di Burano, oasi Wwf. Un paesaggio dove la natura è rimasta inalterata e dove ancora si possono gustare i sapori di una volta, un viaggio non solo in bici, ma anche enogastronomico. CARATTERISTICHE TECNICHE: La maggior parte di questo tour si snoda su strade bianche e tratti asfaltati, ma che non presentano mai traffico intenso, con salite in alcuni punti impegnative e tratti pianeggianti, poche le difficolta tecniche. Il tour è adatto anche per bambini dall’età di 14 anni. MOMENTI INDIMENTICABILI: - i panorami sulle isole dell’Arcipelago Toscano - le Fortezze Spagnole - i borghi di Porto Ercole e Orbetello - i prodotti tipici del mare e della laguna - i resti della la città romana di Cosa - la flora e la fauna tipici di questi luoghi - I Tramonti IL VIAGGIO GIORNO PER GIORNO 1° giorno: arrivo a Orbetello Arrivo e sistemazione in hotel o b&b a Orbetello, importante paese in provincia di Grosseto già conosciuto al tempo degli Etruschi e dei Romani, fino a divenire la sede dello Stato dei Presidi che comprendeva anche tutto il Monte Argentario. -

Capalbio / Wine Tasting After Breakfast, Cycle to the Medieval Town of Capalbio

VBT Itinerary by VBT www.vbt.com Italy: Southern Tuscany & Giglio Island Bike Vacation + Air Package Sweeping seascapes, medieval cities, sprawling vineyards… all of this and more await you during VBT’s Tuscany bike tours. This Southern slip of Tuscan countryside is a cycling paradise kissed by Tyrrhenian sea breezes and ensconced in an Etruscan past. Cycle Maremma’s coastal countryside to the quaint fishing village of Talamone. Pause to swim in glittering blue seas and admire castle-dotted horizons. Take a break from your bike as you journey to Giglio Island and explore its fortressed village. In the ancient town of Capalbio, venture through the city’s cobblestone streets, medieval churches, and shops. Savor locally-hosted farm-to-table banquets and learn to make typical Tuscan desserts. Enjoy guided tours and tastings at family-run olive oil and wine vineyards. This breathtaking route showcases Tuscany’s coastal splendor, medieval roots, and famed rustic culture. Cultural Highlights 1 / 9 VBT Itinerary by VBT www.vbt.com Indulge in the amenities of an agriturismo featured in Condé Nast Traveler Savor fresh farm cuisine during stays at fattorie lodgings Dip your toes, lounge in the sand, or swim in Tyrrhenian Sea beaches Learn from a Tuscan chef how to prepare cantucci almond cookies Taste locally pressed olive oil at a family-run mill Pedal across Orbetello Lagoon, a scenic treasure Walk a panoramic trail with a local guide on Giglio Island What to Expect This tour offers a combination of easy terrain and moderate hills and is ideal for beginning and experienced cyclists. -

Print the Leaflet of the Museum System Monte Amiata

The Amiata Museum system was set up by the Comunità Montana Amiata Santa Caterina Ethnographic Museum CASA MUSEO DI MONTICELLO AMIATA - CINIGIANO Via Grande, Monticello Amiata, Cinigiano (Gr) of Grosseto to valorize the network of thematic and environmental facilities - Roccalbegna Ph. +39 328 4871086 +39 0564 993407 (Comune) +39 0564 969602 (Com. Montana) spread throughout its territory. The System is a territorial container whose Santa Caterina’s ethnographic collection is housed in the www.comune-cinigiano.com special museum identity is represented by the tight relationship between the rooms of an old blacksmith forge. The museum tells the www.sistemamusealeamiata.it environment and landscape values and the anthropological and historical- story of Monte Amiata’s toil, folk customs and rituals tied artistic elements of Monte Amiata. The Amiata Museum system is part of the to fire and trees. The exhibition has two sections: the first MUSEO DELLA VITE E DEL VINO DI MONTENERO D’ORCIA - CASTEL DEL PIANO Maremma Museums, the museum network of the Grosseto province and is a houses a collection of items used for work and household Piazza Centrale 2, Montenero d’Orcia - Castel del Piano (Gr) useful tool to valorize smaller isolated cultural areas which characterize the activities tied to the fire cycle. The second features the Phone +39 0564 994630 (Strada del Vino Montecucco e dei sapori d’Amiata) Tel. +39 0564 969602 (Comunità Montana) GROSSETO’S AMIATA MUSEUMS Amiata territory. “stollo” or haystack pole, long wooden pole which synthe- www.stradadelvinomontecucco.it sizes the Focarazza feast: ancient ritual to honor Santa Ca- www.sistemamusealeamiata.it For the demoethnoanthropological section terina d’Alessandria which is held each year on November we would like to mention: 24th, the most important local feast for the entire com- munity. -

Introduction

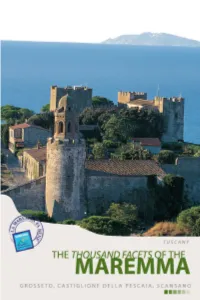

TUSCANY MAREMMA GROSSETO, CASTIGLIONE DELLA PESCAIA, SCANSANO GROSSETO, CASTIGLIONE DELLA PESCAIA, SCANSANO INTRODUCTION cansano, Grosseto, Castiglione della Pescaia: a fresco of hills, planted fields, towns and citadels, sea and beaches, becoming a glowing mosaic embellished by timeless architecture. Here you find one of the most beautiful, warm and Ssincere expressions of the spell cast by the magical Maremma. Qualities lost elsewhere have been carefully nurtured here. The inland is prosperous with naturally fertile farmland that yields high quality, genuine produce. The plain offers GROSSETO, CASTIGLIONE DELLA PESCAIA, SCANSANO THE THOUSAND FACETS OF THE MAREMMA wetlands, rare types of fauna and uncontaminated flora. The sea bathes a coast where flowered beaches, sandy dunes, pine groves and brackish marshes alternate and open into coves with charming tourist ports and modern, well-equipped beaches. What strikes you and may well tie you to this place long after your visit, is the life style you may enjoy the sea, a trip into the Etruscan past, better represented here than anywhere else, then a visit to the villages and towns where the atmosphere and art of the Middle Ages remains firmly embedded. GROSSETO, CASTIGLIONE DELLA PESCAIA, SCANSANO THE THOUSAND FACETS OF THE MAREMMA GROSSETO his beautiful and noble city is the vital centre of the Maremma. Grosseto lies in a green plain traced by the flow of the Ombrone and its origins go back to the powerful Etruscan and Roman city of Roselle. Walking among the military, civil Tand religious monuments, you are able to cover twelve centuries of history and envision each of the periods and rulers as they are unveiled, layer by layer, before you.