Scottish Journal of Performance Volume 2, Issue 2 June 2015 ISSN

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

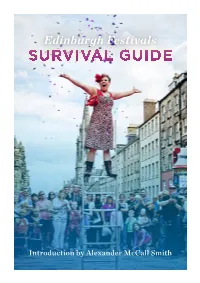

Survival Guide

Edinburgh Festivals SURVIVAL GUIDE Introduction by Alexander McCall Smith INTRODUCTION The original Edinburgh Festival was a wonderful gesture. In 1947, Britain was a dreary and difficult place to live, with the hardships and shortages of the Second World War still very much in evidence. The idea was to promote joyful celebration of the arts that would bring colour and excitement back into daily life. It worked, and the Edinburgh International Festival visitor might find a suitable festival even at the less rapidly became one of the leading arts festivals of obvious times of the year. The Scottish International the world. Edinburgh in the late summer came to be Storytelling Festival, for example, takes place in the synonymous with artistic celebration and sheer joy, shortening days of late October and early November, not just for the people of Edinburgh and Scotland, and, at what might be the coldest, darkest time of the but for everybody. year, there is the remarkable Edinburgh’s Hogmany, But then something rather interesting happened. one of the world’s biggest parties. The Hogmany The city had shown itself to be the ideal place for a celebration and the events that go with it allow many festival, and it was not long before the excitement thousands of people to see the light at the end of and enthusiasm of the International Festival began to winter’s tunnel. spill over into other artistic celebrations. There was How has this happened? At the heart of this the Fringe, the unofficial but highly popular younger is the fact that Edinburgh is, quite simply, one of sibling of the official Festival, but that was just the the most beautiful cities in the world. -

Future of Entertainment Ticketing F Rum London • 19-20 March 2013 Discussion Paper 06

TICKETING TECHNOLOGY THE FUTURE OF ENTERTAINMENT TICKETING F RUM LONDON • 19-20 MARCH 2013 DISCUSSION PAPER 06 The Edinburgh Experience: A Bird’s-Eye View of Clicket.co.uk by Jo Michel, Director, Michel Consultancy The Edinburgh Portal Project was originated to unify the customer experience when searching for events and activities across the city. In this paper, I aim to give you a bird’s-eye view of the experience of those involved in the project which was finally launched in 2011 as www.Clicket.co.uk I came to Edinburgh in June 2008 to be the Ticketing Manager at Hub Tickets, the agency which is operated by the Edinburgh International Festival and sells tickets for “ ...a single point of entry for that festival and many others during the summer visitors, which would offer months each year. product from all the Edinburgh Edinburgh – why a portal? venues...” Edinburgh is a festival city. As everyone knows, it is the home of the largest of them all: the Edinburgh Festival Fringe; the prestigious Edinburgh International Festival; The Edinburgh Book Festival; Edinburgh Jazz & Blues Festival; Structure and strategy Festival of Politics; and Festival of Spirituality and Peace all of The Audience Business (TAB) was appointed as the project which run concurrently throughout August, each year. management and a Strategy Working Group put in place to Edinburgh is also home to the renowned Traverse Theatre guide the decision making process and to be representative Company, has great touring venues in the Festival Theatre of the core stakeholders in the project. The Edinburgh Portal and Edinburgh Playhouse, the beautiful Queens Hall and a Project had begun. -

Press Release Disabled Leaders Send Open Letter

PRESS RELEASE FOR IMMEDIATE USE 9 June 2020 LEADING DISABLED ARTISTS & CULTURAL LEADERS SEND OPEN LETTER TO UK CULTURE MINISTERS DEMANDING SUPPORT FOR DISABLED PEOPLE IN THE CREATIVE INDUSTRIES #WeShallNotBeRemoved Over 100 leading disabled artists and cultural leaders have today sent an open letter to The Secretary of State for Culture Oliver Dowden MP and devolved UK Culture Ministers, demanding safeguards to protect the future of disability arts in the UK as a consequence of Covid19. Signatories include high profile disabled creatives including actors Mat Fraser & Nabil Shaban, visual artists Tony Heaton & Ashok Mistry, percussionist Dame Evelyn Glennie, poet Jamie Hale, broadcasters Samantha Renke & Mik Scarlet, film director Justin Edgar, performer Jess Thom, theatre directors Jenny Sealey, Amit Sharma, & Vici Wreford-Sinnott and Disability Champion for Arts & Culture, Andrew Miller. The letter warns that the pandemic has magnified inequalities for disabled people working in the creative industries and that many are facing long term shielding, loss of income and invisibility in wider society. Disabled cultural leaders are calling on the government to extend the Self Employment Income Support Scheme (SEISS) beyond August, to prioritise involvement of disabled people in cultural policy, to ensure the renewal and recovery of the cultural sector is more inclusive and offers greater access and representation. The open letter was organised by the new UK Disability Arts Alliance #WeShallNotBeRemoved. The alliance is an emergency response led by disabled people for disabled people working across the UK’s creative industries in every capacity and across artforms. Andrew Miller, UK Government Disability Champion for Arts & Culture said: “The speed of recovery planning risks excluding many creative disabled people. -

Hidden Edinburgh Challenge

Hidden Edinburgh Challenge Created for the Senior Section Spectacular 2016 Introduction The Hidden Edinburgh Challenge is designed for Rainbows, Brownies, Guides, the Senior Section, Leaders and Trefoil members. It has been designed by Girlguiding Edinburgh’s ‘Team Spectacular’, to showcase some of Edinburgh’s hidden treasures, and to give you an opportunity to explore this beautiful city through a range of activities that can be completed in the unit meeting place, and out and about around the city. The badge accompanying this challenge is circular, with a 3-inch diameter and gold accenting. It features a unicorn, Girlguiding Edinburgh’s Senior Section Spectacular mascot. Badges cost £1 each plus P&P. This challenge has been produced to raise funds for Girlguiding Edinburgh’s Senior Section Spectacular activities, and to contribute towards further Senior Section activities following 2016. To earn the badge, Rainbows gain 60 points, Brownies 70 points, Guides 80 points, Senior Section/Leaders/Trefoil Members 100 points. You should complete at least 10 points from each of Places and Spaces, Unicorns, and Guiding. The rest of your points can come from sections of your choice. We have tried to include a range of activities to suit all ages and abilities, but please feel free to adapt any of the activities to suit participants as needed. Badges can be ordered using the order form on the last page. We hope you have fun completing this challenge and exploring our beautiful city. Please share your photos and stories with us by emailing Team Spectacular at [email protected]! Places and Spaces Edinburgh is full of weird and wonderful places. -

Chronicle February 2011

picturethis THECHRONICLE £50 voucher to be won See page 15 for FEBRUARY 2011 Issue No. 125 Free competition details INSIDE THIS ISSUE COMMUNITY IN FOCUS Carr-Gomm Scotland page 3 VOTE FOR TAMARA! BINGHAM RESIDENTS SAY Dance sensation RESPITE PLANS LEAVE in final of Sky1’s ‘Got to Dance’ THEM OUT IN THE COLD page 16 By Phil Harris January, with the suggested change. Local resident Gail Ross said: ple and community. So why move He told the Chronicle: “Going by “Let’s be honest. The children and something else in. It’s no advan- WIN TICKETS TO COUNCIL PLANS TO relocate the press statement, they [the families using Seaview aren’t tage to the people that live here. the Seaview Children’s Respite council] had been preparing this going to put any money into this It’s not right and it’s not fair.” SEE THE MAGIC Centre from Portobello to the behind closed doors but this is just community. We had promises Bingham resident and youth OF MOTOWN site of the former Lismore the start of the pre-planning con- when they came for the school but worker at the local community Primary School in Bingham, sultation. They [the council] need they never happened. centre, Margaret Paterson, added: have met with oppostition from to get the views and objections of “At the moment in Bingham we “I feel that Bingham has had a raw local residents. the locals before going to the have six care facilities. One of deal. Once upon a time we had a Concerns were raised at the expense of drawing up proper these is a homeless unit and we butcher, baker, fishmonger, post Bingham Neighbourhood plans and submitting them. -

Explore the Character of Edinburgh, Scotland (Europe) for Seven Days & Six Nights at Your Choice of the Radisson Blu Hotel

Explore the Character of Edinburgh, Scotland (Europe) for Seven Days & Six Nights at Your Choice of the Radisson Blu Hotel, The Principal Edinburgh Charlotte Square, the Macdonald Holyrood, or the Apex International Hotel with Economy Class Air for Two Escape to vibrant Edinburgh, where history and modernity meet in a cosmopolitan city set against the striking landscape of Scotland. Originally Scotland's defensive fortress for hundreds of years with its position presiding over the North Sea, Edinburgh is now a must-see destination. Visit its namesake Edinburgh Castle, home to the 12th-century St. Margaret's Chapel, and wander the cobblestone streets that lead to fantastic dining, rambunctious taverns and exciting shopping. A beautiful and cultured city, you will find a wealth of things to do in Edinburgh. Discover nearby historic attractions like the shops along Princes Street, the National Museum of Scotland or the Scotch Whisky Heritage Centre, all within walking distance of the hotels. Start your Royal Mile journey at Edinburgh Castle and take in the dramatic panorama over Scotland's capital. From there, walk down the cobbled street past the St. Giles Cathedral, John Knox's House and shops selling Scottish crafts and tartan goods. At the end of the Mile, you'll find a uniquely Scottish marriage of old and new power, where Holyrood Palace sits opposite the Scottish Parliament. After a day spent sightseeing, Edinburgh at night is not to be missed. Take in a show at the Edinburgh Playhouse, enjoy a meal at one of Edinburgh's Michelin-starred restaurants or dance the night away in the lively clubs on George Street or the Cowgate. -

International-Festival-Brochure-2019-Digital-Lo-Rez.Pdf

1 1 2–26 August 2019 eif.co.uk #edintfest Thank you to our Thank you to our Supporters Funders and Sponsors Public Funders Opening Event Partner Principal Supporters Dunard Fund American Friends of the Edinburgh Léan Scully EIF Fund International Festival James and Morag Anderson Edinburgh International Festival Fireworks Concert Partner Sir Ewan and Lady Brown Endowment Fund Festival Partners Benefactors Trusts and Corporate Donations Geoff and Mary Ball Richard and Catherine Burns Joscelyn Fox Roxane Clayton Project support The Badenoch Trust Gavin and Kate Gemmell Sheila Colvin The Calateria Trust Donald and Louise MacDonald Lori A. Martin and The Castansa Trust Anne McFarlane Christopher L. Eisgruber The John S Cohen Foundation Keith and Andrea Skeoch Flure Grossart Cullen Property Dr. George Sypert and Professor Ludmilla Jordanova The Peter Diamand Trust Dr. Joy Arpin Niall and Carol Lothian The Evelyn Drysdale Claire and Mark Urquhart Bridget and John Macaskill Principal Sponsors and Supporters Charitable Trust Vivienne and Robin Menzies The Educational Institute Binks Trust Keith and Lee Miller of Scotland Cruden Foundation Limited Brenda Rennie The Elgar Society The Negaunee Foundation George Ritchie Edwin Fox Foundation The Pirie Rankin Charitable Trust Michael Shipley and Philip Gordon Fraser Charitable Trust The Stevenston Charitable Trust Rudge Miss K M Harbinson’s Jim and Isobel Stretton Charitable Trust Andrew and Becky Swanston The Inches Carr Trust Major Sponsors Susie Thomson H I McMorran Charitable Mr Hedley G Wright -

34764 633851756427921507.Pdf

www.thecubeedinburgh.co.uk The Cube has been designed to be an iconic building reflecting Edinburgh’s vibrant 21st Century business status. The contemporary architecture of The Cube marries Edinburgh’s World Heritage Status with the cut and thrust of commerce. It will be a place of work benefiting from all the city centre amenities yet enjoying the openness of Calton Hill. THE CUBE contents compelling & assured 3 3 the idea sense of place & unique 5 3 location forward thinking & future proof 13 3 aspirational straightforward & flexible 19 3 space 2 THE CUBE compelling & assured Take a plan and watch how it shapes up. The Cube is being developed by The Cube exudes confidence. In a one of Scotland’s leading property prestigious location, next to the city’s companies, Kilmartin Property big occupiers, at the heart of a World Group. Designed by award-winning Heritage site. The Cube will stand Allan Murray Architects and out, proud of its place in a famous, constructed by leading contractor changing capital. A contemporary Sir Robert McAlpine, the delivery solution, offering approximately team has an extensive track 67,000 sq ft of space over six flexible record of developing and creating and efficient floorplates. inspirational space. On time and to the highest specification. Leith Street is a minute’s walk from Waverley Station and Princes Street. The site offers an irresistible Developing this site has been about opportunity, facing the urban city much more than simply filling a centre and with views over the corner. It’s been about building on parkland of Calton Hill. -

Explore the Character of Edinburgh, Scotland (Europe) for Seven Days

Explore the Character of Edinburgh, Scotland (Europe) for Seven Days & Six Nights at Your Choice of the Radisson Blu Hotel, The George, the Macdonald Holyrood, or the Apex International Hotel with Economy Class Air for Two Escape to vibrant Edinburgh, where history and modernity meet in a cosmopolitan city set against the striking landscape of Scotland. Originally Scotland's defensive fortress for hundreds of years with its position presiding over the North Sea, Edinburgh is now a must-see destination. Visit its namesake Edinburgh Castle, home to the 12th-century St. Margaret's Chapel, and wander the cobblestone streets that lead to fantastic dining, rambunctious taverns and exciting shopping. A beautiful and cultured city, you will find a wealth of things to do in Edinburgh. Discover nearby historic attractions like the shops along Princes Street, the National Museum of Scotland or the Scotch Whisky Heritage Centre, both within walking distance of the hotel. Start your Royal Mile journey at Edinburgh Castle and take in the dramatic panorama over Scotland's capital. From there, walk down the cobbled street past the St. Giles Cathedral, John Knox's House and shops selling Scottish crafts and tartan goods. At the end of the Mile, you'll find a uniquely Scottish marriage of old and new power, where Holyrood Palace sits opposite the Scottish Parliament. After a day spent sightseeing, Edinburgh at night is not to be missed. Take in a show at the Edinburgh Playhouse, enjoy a meal at one of Edinburgh's Michelin-starred restaurants or dance the night away in the lively clubs on George Street or the Cowgate. -

This Is Edinburgh Information Pack Summer 2017

1 This is Edinburgh Information Pack Summer 2017 edinburgh.org /Edinburgh @edinburgh thisisedinburgh 2 · This is Edinburgh 3 “ The city whispers: come Edinburgh’s beauty is both staggering and Look at me, listen to the beating of my heart inimitable. But, the city is far more than just I am the place you have seen in dreams a pretty face. Take a closer look and there’s I am a stage for you to play upon much more to discover. I am Edinburgh” Our shopping ranges from the world’s best luxury names, to local, independent talent Alexander McCall Smith just waiting to be discovered. Our food, be it Michelin-starred, or pop-up street-food with award-winning chefs, is mouthwateringly delicious. From the rich – sometimes hidden – history that surrounds your every step, to the wealth of lush, green spaces peppered around the city centre, Edinburgh continually surprises, delights and inspires. Join us and find out why there’s nowhere in the world quite like Scotland’s capital city. Contents Heritage 4 Culture and events 8 Attractions 14 Food and drink 18 Shopping 22 Stay 26 Awards 28 Fast facts 30 10 things 31 Social media 32 4 · This is Edinburgh 5 Edinburgh’s Heritage Royal Mile Calton Hill The Royal Mile is at the centre of Edinburgh’s Old Town Of all places for a view, this Calton Hill is perhaps the best Edinburgh has been inhabited since the and as its name suggests, the thoroughfare is one mile – Robert Louis Stevenson, 1889. long. With Edinburgh Castle at its head and the Palace of Bronze Age; its first settlement can be traced Holyroodhouse at its foot, The Royal Mile features many Home to some of Edinburgh’s most iconic monuments and historic buildings; Gladstone’s Land, The Real Mary King’s one of the city’s most picturesque locations, Calton Hill to a hillfort established in the area, most likely Close and John Knox House to name but a few. -

Backstage in Biscuit Land by Touretteshero

Marketing Pack: Backstage in Biscuit Land BACKSTAGE IN BISCUIT LAND BY TOURETTESHERO TITLE AND CREDITS Co-Creators - Jess Thom, Jess Mabel Jones, Matthew Pountney Produced by Jolie Booth and Matthew Pountney Supported by Unlimited, Graeae & Battersea Arts Centre COMPANY INFORMATION Jessica Thom Jess is co-founder of Touretteshero and may or may not lead a secret double life as a superhero. Artist, playworker, and expert fundraiser, Jess currently helps coordinate a large play project in South London. Jess has had tics since she was a child but wasn’t diagnosed with Tourettes until she was in her twenties. With some encouragement from her friends, Jess decided to turn her tics into a source of imaginative creativity and the Touretteshero project was born. Jess Mabel Jones Performer, puppeteer and co-creator of the award winning Backstage In Biscuit Land, Jess, AKA Chopin, has become an integral part of the Touretteshero family. Jess is also Associate Director of Finger in The Pie and programmer of their prestigious Finger in The Pie Cabaret. Marketing Pack: Backstage in Biscuit Land Matthew Pountney Matthew is co-founder of Touretteshero and rumour has it he might be a Leftwing Idiot. He’s been friends with Jess for over a decade and they’ve worked together on a large number of creative projects for children during that time. Jolie Booth Producer, performer and Essex girl Jolie works with a portfolio of companies that includes Tangram Theatre Company, Hertford Theatre, Harlow Playhouse and, of course, Touretteshero. If you’re lucky you might just catch her dressed as a cat (dressed as a nun). -

This Is Edinburgh Information Pack Winter 2017-18

1 This is Edinburgh Information Pack Winter 2017-18 edinburgh.org /Edinburgh @edinburgh thisisedinburgh 2 · This is Edinburgh 3 “ The city whispers: come Edinburgh’s beauty is both staggering and Look at me, listen to the beating of my heart inimitable. But, the city is far more than just I am the place you have seen in dreams a pretty face. Take a closer look and there’s much I am a stage for you to play upon more to discover. I am Edinburgh” Our shopping ranges from the world’s best luxury names, to local, independent talent just waiting to Alexander McCall Smith be discovered. Our food, be it Michelin-starred, or pop-up street-food with award-winning chefs, is mouthwateringly delicious. From the rich – sometimes hidden – history that surrounds your every step, to the wealth of lush, green spaces peppered around the city centre, Edinburgh continually surprises, delights and inspires. Join us and find out why there’s nowhere in the world quite like Scotland’s capital city. Contents Heritage 4 Culture and events 8 Attractions 14 Food and drink 18 Shopping 22 Stay 26 Awards 28 Fast facts 30 10 things 31 Social media 32 4 · This is Edinburgh 5 Edinburgh’s Heritage Royal Mile Calton Hill The Royal Mile is at the centre of Edinburgh’s Old Town and Of all places for a view, this Calton Hill is perhaps the best – as its name suggests, the thoroughfare is one mile long. With Robert Louis Stevenson, 1889. Edinburgh has been inhabited since the Bronze Edinburgh Castle at its head and the Palace of Holyroodhouse at its foot, The Royal Mile features many historic buildings; Home to some of Edinburgh’s most iconic monuments and one Age; its first settlement can be traced to a hillfort Gladstone’s Land, The Real Mary King’s Close and John Knox of the city’s most picturesque locations, Calton Hill helped to House to name but a few.