National Case Law on Freedom of Expression

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Flash Reports on Labour Law January 2017 Summary and Country Reports

Flash Report 01/2017 Flash Reports on Labour Law January 2017 Summary and country reports EUROPEAN COMMISSION Directorate DG Employment, Social Affairs and Inclusion Unit B.2 – Working Conditions Flash Report 01/2017 Europe Direct is a service to help you find answers to your questions about the European Union. Freephone number (*): 00 800 6 7 8 9 10 11 (*) The information given is free, as are most calls (though some operators, phone boxes or hotels may charge you). LEGAL NOTICE This document has been prepared for the European Commission however it reflects the views only of the authors, and the Commission cannot be held responsible for any use which may be made of the information contained therein. More information on the European Union is available on the Internet (http://www.europa.eu). Luxembourg: Publications Office of the European Union, 2017 ISBN ABC 12345678 DOI 987654321 © European Union, 2017 Reproduction is authorised provided the source is acknowledged. Flash Report 01/2017 Country Labour Law Experts Austria Martin Risak Daniela Kroemer Belgium Wilfried Rauws Bulgaria Krassimira Sredkova Croatia Ivana Grgurev Cyprus Nicos Trimikliniotis Czech Republic Nataša Randlová Denmark Natalie Videbaek Munkholm Estonia Gaabriel Tavits Finland Matleena Engblom France Francis Kessler Germany Bernd Waas Greece Costas Papadimitriou Hungary Gyorgy Kiss Ireland Anthony Kerr Italy Edoardo Ales Latvia Kristine Dupate Lithuania Tomas Davulis Luxemburg Jean-Luc Putz Malta Lorna Mifsud Cachia Netherlands Barend Barentsen Poland Leszek Mitrus Portugal José João Abrantes Rita Canas da Silva Romania Raluca Dimitriu Slovakia Robert Schronk Slovenia Polonca Končar Spain Joaquín García-Murcia Iván Antonio Rodríguez Cardo Sweden Andreas Inghammar United Kingdom Catherine Barnard Iceland Inga Björg Hjaltadóttir Liechtenstein Wolfgang Portmann Norway Helga Aune Lill Egeland Flash Report 01/2017 Table of Contents Executive Summary .............................................. -

Section 7: Criminal Offense, Criminal Responsibility, and Commission of a Criminal Offense

63 Section 7: Criminal Offense, Criminal Responsibility, and Commission of a Criminal Offense Article 15: Criminal Offense A criminal offense is an unlawful act: (a) that is prescribed as a criminal offense by law; (b) whose characteristics are specified by law; and (c) for which a penalty is prescribed by law. Commentary This provision reiterates some of the aspects of the principle of legality and others relating to the purposes and limits of criminal legislation. Reference should be made to Article 2 (“Purpose and Limits of Criminal Legislation”) and Article 3 (“Principle of Legality”) and their accompanying commentaries. Article 16: Criminal Responsibility A person who commits a criminal offense is criminally responsible if: (a) he or she commits a criminal offense, as defined under Article 15, with intention, recklessness, or negligence as defined in Article 18; IOP573A_ModelCodes_Part1.indd 63 6/25/07 10:13:18 AM 64 • General Part, Section (b) no lawful justification exists under Articles 20–22 of the MCC for the commission of the criminal offense; (c) there are no grounds excluding criminal responsibility for the commission of the criminal offense under Articles 2–26 of the MCC; and (d) there are no other statutorily defined grounds excluding criminal responsibility. Commentary When a person is found criminally responsible for the commission of a criminal offense, he or she can be convicted of this offense, and a penalty or penalties may be imposed upon him or her as provided for in the MCC. Article 16 lays down the elements required for a finding of criminal responsibility against a person. -

Freedom of Expression

! BRIEFING NOTE SERIES Freedom of Expression Centre for Law and Democracy International Media Support (IMS) ! FREEDOM OF EXPRESSION BRIEFING NOTE SERIES July 2014 ! This publication was produced with the generous support of the governments of Denmark, Sweden and Norway. ! Centre for Law and Democracy (CLD) International Media Support (IMS) 39 Chartwell Lane Nørregade 18 Halifax, N.S. 1165 Copenhagen K B3M 3S7 Denmark Canada Tel: +1 902 431-3688 Tel: +45 8832 7000 Fax: +1 902 431-3689 Fax: +45 3312 0099 Email: [email protected] Email: [email protected] www.law-democracy.org www.mediasupport.org © CLD, Halifax and IMS, Copenhagen ISBN 978-87-92209-62-7 This work is licenced under the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International licence. To view a copy of this licence, visit: http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-sa/4.0/ You are free to copy, distribute and display this work and to make derivative works, provided you give credit to Centre for Law and Democracy and International Media Support; do not use this work for commercial purposes; and distribute any works derived from this publication under a licence identical to this one. ! Abbreviations ACHR American Convention on Human Rights COE Council of Europe ECHR European Court of Human Rights ICCPR International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights ICT Information and communications technology IPC Indonesia Press Council OAS Organization of American States OSCE Organization for Security and Co-operation in Europe PKK Kurdistan Workers’ Party PSB Public service -

Nvcc College-Wide Course Content Summary Lgl 218 - Criminal Law (3 Cr.)

NVCC COLLEGE-WIDE COURSE CONTENT SUMMARY LGL 218 - CRIMINAL LAW (3 CR.) COURSE DESCRIPTION Focuses on major crimes, including their classification, elements of proof, intent, conspiracy, responsibility, parties, and defenses. Emphasizes Virginia law. May include general principles of applicable Constitutional law and criminal procedure. Lecture 3 hours per week. GENERAL COURSE PURPOSE This course is designed to introduce the student to the various substantive and procedural areas of criminal law. ENTRY LEVEL COMPETENCIES Although there are no prerequisites for this course, proficiency (at the high school level) in spoken and written English is recommended for its successful completion. COURSE OBJECTIVES Upon completion of this course, the student should be able to: - describe the structure of the criminal justice system - describe the elements of various federal and Virginia state crimes - understand the ways in which a person can become a party to a crime - describe the elements of various affirmative defenses to federal and Virginia state crimes - understand the basic structure of the law governing arrest, search and seizure, and recognize Constitutional issues posed in these areas - describe the stages of criminal proceedings, in both federal and state courts, and assist a prosecutor or defense lawyer at each stage of such proceedings MAJOR TOPICS TO BE INCLUDED - crimes versus moral wrongs - felonies vs. misdemeanors - criminal capacity - actus reas, mens rea and causation - elements of various federal and Virginia state crimes - inchoate crimes: attempt, solicitation, and conspiracy - parties to a crime - affirmative defenses - insanity - probable cause - arrest, with and without a warrant - search and seizure, with and without a warrant - grand jury indictments - bail and pretrial release - pretrial proceedings - steps of trial and appeal EXTRA TOPICS WHICH MAY BE INCLUDED - purposes of criminal law and punishment - sentencing, probation and parole - special issues posed by mental illness - special issues posed by the death penalty . -

The Right to Freedom of Thought, Conscience and Religion Or Belief

Level 1, 4 Campion St 594 St Kilda Rd DEAKIN ACT 2600 MELBOURNE VIC 3004 T 02 6259 0431 T 02 6171 7446 E [email protected] E [email protected] 14 February 2018 The Expert Panel on Religious Freedom C/o Department of the Prime Minister and Cabinet By email: [email protected] RE: Submission to the Commonwealth Expert Panel on Religious Freedom 1. The Human Rights Law Alliance and the Australian Christian Lobby welcome this opportunity to make a submission to the Inquiry into the Status of the Human Right to Freedom of Religion or Belief. 2. The Human Rights Law Alliance implements legal strategies to protect and promote fundamental human rights. It does this by resourcing legal cases with funding and expertise to create rights-protecting legal precedents. The Alliance is especially concerned to protect and promote the right to freedom of thought, conscience and religion or belief. In the past 24 months, the Alliance has aided more than 30 legal cases, and allied lawyers appeared in State Tribunals and Magistrates, District and Supreme Courts as well as the Federal Court. 3. With more than 100,000 supporters, ACL facilitates professional engagement and dialogue between the Christian constituency and government, allowing the voice of Christians to be heard in the public square. ACL is neither party partisan or denominationally aligned. ACL representatives bring a Christian perspective to policy makers in Federal, State and Territory parliaments. 4. This submission focusses on the intersection between freedom of religion and other human rights first in international law, second in Australian law, and third in the lived experience of Australians. -

19-292 Torres V. Madrid (03/25/2021)

(Slip Opinion) OCTOBER TERM, 2020 1 Syllabus NOTE: Where it is feasible, a syllabus (headnote) will be released, as is being done in connection with this case, at the time the opinion is issued. The syllabus constitutes no part of the opinion of the Court but has been prepared by the Reporter of Decisions for the convenience of the reader. See United States v. Detroit Timber & Lumber Co., 200 U. S. 321, 337. SUPREME COURT OF THE UNITED STATES Syllabus TORRES v. MADRID ET AL. CERTIORARI TO THE UNITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS FOR THE TENTH CIRCUIT No. 19–292. Argued October 14, 2020—Decided March 25, 2021 Respondents Janice Madrid and Richard Williamson, officers with the New Mexico State Police, arrived at an Albuquerque apartment com- plex to execute an arrest warrant and approached petitioner Roxanne Torres, then standing near a Toyota FJ Cruiser. The officers at- tempted to speak with her as she got into the driver’s seat. Believing the officers to be carjackers, Torres hit the gas to escape. The officers fired their service pistols 13 times to stop Torres, striking her twice. Torres managed to escape and drove to a hospital 75 miles away, only to be airlifted back to a hospital in Albuquerque, where the police ar- rested her the next day. Torres later sought damages from the officers under 42 U. S. C. §1983. She claimed that the officers used excessive force against her and that the shooting constituted an unreasonable seizure under the Fourth Amendment. Affirming the District Court’s grant of summary judgment to the officers, the Tenth Circuit held that “a suspect’s continued flight after being shot by police negates a Fourth Amendment excessive-force claim.” 769 Fed. -

The Supreme Court and the New Equity

Vanderbilt Law Review Volume 68 | Issue 4 Article 1 5-2015 The uprS eme Court and the New Equity Samuel L. Bray Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarship.law.vanderbilt.edu/vlr Part of the Supreme Court of the United States Commons Recommended Citation Samuel L. Bray, The uS preme Court and the New Equity, 68 Vanderbilt Law Review 997 (2019) Available at: https://scholarship.law.vanderbilt.edu/vlr/vol68/iss4/1 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by Scholarship@Vanderbilt Law. It has been accepted for inclusion in Vanderbilt Law Review by an authorized editor of Scholarship@Vanderbilt Law. For more information, please contact [email protected]. VANDERBILT LAW REVIEW VOLUME 68 MAY 2015 NUMBER 4 ARTICLES The Supreme Court and the New Equity Samuel L. Bray* The line between law and equity has largely faded away. Even in remedies, where the line persists, the conventional scholarly wisdom favors erasing it. Yet something surprisinghas happened. In a series of cases over the last decade and a half, the U.S. Supreme Court has acted directly contrary to this conventional wisdom. These cases range across many areas of substantive law-from commercial contracts and employee benefits to habeas and immigration, from patents and copyright to environmental law and national security. Throughout these disparate areas, the Court has consistently reinforced the line between legal and equitable remedies, and it has treated equitable remedies as having distinctive powers and limitations. This Article describes and begins to evaluate the Court's new equity cases. -

Freedom of Information: a Comparative Legal Survey

JeXo C[dZ[b ^h i]Z AVl J^[_cfehjWdY[e\j^[h_]^jje Egd\gVbbZ9^gZXidgl^i]6GI>8A:&.!<adWVa 8VbeV^\c [dg ;gZZ :megZhh^dc! V aZVY^c\ _d\ehcWj_edehj^[h_]^jjeadem_iWd ^ciZgcVi^dcVa ]jbVc g^\]ih C<D WVhZY ^c _dYh[Wi_d]boYedijWdjh[\hW_d_dj^[ AdcYdc! V edh^i^dc ]Z ]Vh ]ZaY [dg hdbZ iZc nZVgh# >c i]Vi XVeVX^in! ]Z ]Vh ldg`ZY cekj^ie\Z[l[befc[djfhWYj_j_ed[hi" ZmiZch^kZan dc [gZZYdb d[ ZmegZhh^dc VcY g^\]i id ^c[dgbVi^dc ^hhjZh ^c 6h^V! 6[g^XV! Y_l_bieY_[jo"WYWZ[c_Yi"j^[c[Z_WWdZ :jgdeZ! i]Z B^YYaZ :Vhi VcY AVi^c 6bZg^XV! ]el[hdc[dji$M^Wj_ij^_ih_]^j"_i_j gjcc^c\ igV^c^c\ hZb^cVgh! Xg^i^fj^c\ aVlh! iV`^c\XVhZhidWdi]cVi^dcVaVcY^ciZgcVi^dcVa h[WbboWh_]^jWdZ^em^Wl[]el[hdc[dji WdY^Zh! VYk^h^c\ C<Dh VcY \dkZgcbZcih! VcY ZkZc ldg`^c\ l^i] d[ÒX^Vah id egZeVgZ iek]^jje]_l[[\\[Yjje_j5J^[i[Wh[ YgV[ig^\]iid^c[dgbVi^dcaVlh#>cVYY^i^dcid iec[e\j^[gk[ij_edij^_iXeeai[[ai ]^h ldg` l^i] 6GI>8A:&.! ]Z ]Vh egdk^YZY ZmeZgi^hZ dc i]ZhZ ^hhjZh id V l^YZ gVc\Z jeWZZh[ii"fhel_Z_d]WdWYY[ii_Xb[ d[ VXidgh ^cXajY^c\ i]Z LdgaY 7Vc`! kVg^djh JCVcYdi]Zg^ciZg\dkZgcbZciVaWdY^Zh!VcY WYYekdje\j^[bWmWdZfhWYj_Y[h[]WhZ_d] cjbZgdjh C<Dh# Eg^dg id _d^c^c\ 6GI>8A: \h[[Zece\_d\ehcWj_ed"WdZWdWdWboi_i &.!IdWnBZcYZaldg`ZY^c]jbVcg^\]ihVcY ^ciZgcVi^dcVa YZkZadebZci! ^cXajY^c\ Vh V e\m^Wj_imeha_d]WdZm^o$ hZc^dg ]jbVc g^\]ih XdchjaiVci l^i] Dm[Vb 8VcVYVVcYVhV]jbVcg^\]iheda^XnVcVanhi 68dbeVgVi^kZAZ\VaHjgkZn Vi i]Z 8VcVY^Vc >ciZgcVi^dcVa 9ZkZadebZci ;gZZYdbd[>c[dgbVi^dc/ 6\ZcXn8>96# ÆJ^[\h[[Ôeme\_d\ehcWj_edWdZ_Z[Wi IdWn BZcYZa ]Vh ejWa^h]ZY l^YZan! b_[iWjj^[^[Whje\j^[l[hodej_ede\ 6 8dbeVgVi^kZ AZ\Va HjgkZn Xdcig^Wji^c\ id cjbZgdjh 6GI>8A: &. -

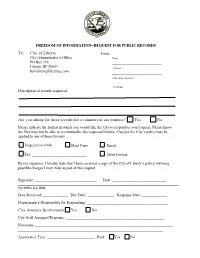

FOIA--Public Records Request

FREEDOM OF INFORMATION--REQUEST FOR PUBLIC RECORDS To: City of Liberty From: __________________________ City Administrator’s Office Name PO Box 716 __________________________ Liberty, SC 29657 Address [email protected] __________________________ City, State, Zip Code __________________________ Telephone Description of records requested: Are you asking for these records for a commercial use/purpose? Yes No Please indicate the format in which you would like the City to respond to your request. Please know the City may not be able to accommodate the requested format. Cost per the City’s policy may be applied to any of these formats. Inspection Only Hard Copy Email: ___________________________ Fax: ____________________________ Other Format: _____________________ By my signature, I hereby state that I have received a copy of the City of Liberty’s policy outlining possible charges I may incur as part of this request. Signature: ________________________________ Date: ____________________________ For Office Use Only: Date Received: _____________ Due Date: ______________ Response Date: _____________ Department(s) Responsible for Responding: __________________________________________ City Attorney Involvement: Yes No City Staff Assigned Response: ___________________________________________________ Notations:________________________________________________________________________ ___________________________________________________________________________ Associated Fees: _______________________ Paid: Yes No FREEDOM OF INFORMATION POLICY The City of Liberty upholds the Public’s right to know the activities of its government, but finds it necessary to adopt a written policy to advise its employees. With regard to our own records, this office discloses records in compliance with the state’s Freedom of Information Act. All FOIA requests must be submitted in writing and will be responded to within ten (10) business days unless the records are more than 24 months old, then it will be responded to within twenty (20) business days. -

The Freedom of Academic Freedom: a Legal Dilemma

Chicago-Kent Law Review Volume 48 Issue 2 Article 4 October 1971 The Freedom of Academic Freedom: A Legal Dilemma Luis Kutner Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarship.kentlaw.iit.edu/cklawreview Part of the Law Commons Recommended Citation Luis Kutner, The Freedom of Academic Freedom: A Legal Dilemma, 48 Chi.-Kent L. Rev. 168 (1971). Available at: https://scholarship.kentlaw.iit.edu/cklawreview/vol48/iss2/4 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by Scholarly Commons @ IIT Chicago-Kent College of Law. It has been accepted for inclusion in Chicago-Kent Law Review by an authorized editor of Scholarly Commons @ IIT Chicago-Kent College of Law. For more information, please contact [email protected], [email protected]. THE FREEDOM OF ACADEMIC FREEDOM: A LEGAL DILEMMA Luis KUTNER* Because modern man in his search for truth has turned away from kings, priests, commissars and bureaucrats, he is left, for better or worse, with professors. -Walter Lippman. Complete liberty of contradicting and disproving our opinion is the very condition which justifies us in assuming its truth for purposes of action.... -John Stuart Mill, On Liberty. I. INTRODUCTION IN THESE DAYS of crisis in higher education, part of the threat to aca- demic freedom-which includes the concepts of freedom of thought, inquiry, expression and orderly assembly-has come, unfortunately, from certain actions by professors, who have traditionally enjoyed the protection that academic freedom affords. While many of the professors who teach at American institutions of higher learning are indeed competent and dedicated scholars in their fields, a number of their colleagues have allied themselves with student demonstrators and like organized groups who seek to destroy the free and open atmosphere of the academic community. -

Freedom of Thought, Conscience and Religion

Freedom of thought, COUNCIL CONSEIL conscience OF EUROPE DE L’EUROPE and religion A guide to the implementation of Article 9 of the European Convention on Human Rights Jim Murdoch Human rights handbooks, No. 9 HRHB9_EN.book Page 1 Tuesday, June 26, 2007 4:08 PM HRHB9_EN.book Page 1 Tuesday, June 26, 2007 4:08 PM Freedom of thought, conscience and religion A guide to the implementation of Article 9 of the European Convention on Human Rights Jim Murdoch Human rights handbooks, No. 9 HRHB9_EN.book Page 2 Tuesday, June 26, 2007 4:08 PM In the “Human rights handbooks” series: No. 1: The right to respect for private No. 6: The prohibition of torture. A Directorate General and family life. A guide to the implemen- guide to the implementation of Article 3 of Human Rights tation of Article 8 of the European Con- of the European Convention on Human and Legal Affairs vention on Human Rights (2001) Rights (2003) Council of Europe F-67075 Strasbourg Cedex No. 2: Freedom of expression. A guide to the implementation of Article 10 of the No. 7 : Positive obligations under the © Council of Europe, 2007 European Convention on Human Rights European Convention on Human Cover illustration © Sean Nel – Fotolia.com (2001) Rights. A guide to the implementation of No. 3: The right to a fair trial. A guide to the European Convention on Human 1st printing, June 2007 the implementation of Article 6 of the Rights (2007) Printed in Belgium European Convention on Human Rights (2001; 2nd edition, 2006) No. 8: The right to life. -

Detailed Table of Contents (PDF Download)

CONTENTS Preface to the Third Edition xxix Preface to the Second Edition xxxiii Preface to the First Edition xxxix Acknowledgments xiv PART I INTRODUCTION 1 CHAPTER 1 THE IDEA OF INTERNATIONAL AND TRANSNATIONAL CRIMINAL LAW 3 A. What Are International and Transnational Criminal Law? 3 1. Transnational Criminal Law 3 2. International Crimes 4 3. Treaty-Based Domestic Crimes 5 B. What Is Criminal Law? 6 Henry M. Hart, Jr., The Aims of the Criminal Law 6 Notes and Questions 7 C. Crime and Punishment 9 Prosecutor v. Blaškic´ 14 Notes and Questions 14 D. The Need for Safeguards in the Criminal Law 14 1. The Risk of Overenforcement 15 John Hasnas, Once More Unto the Breach: The Inherent Liberalism of the Criminal Law and Liability for Attempting the Impossible 15 2. The Basic Protections in Criminal Law and Procedure 16 E. Is International Criminal Law Different? The Eichmann Trial 18 Prosecutor v. Eichmann 20 Mark Osiel, Mass Atrocity, Collective Memory, and the Law 21 Hannah Arendt, Eichmann in Jerusalem: A Report on the Banality of Evil 23 Notes and Questions 23 xi xii Contents CHAPTER 2 INTERNATIONAL LAW PRELIMINARIES 29 A. The Classical Picture of International Law 29 1. Historical Overview 30 a. Westphalian Sovereignty 31 Island of Palmas (United States v. Netherlands) 32 Questions 33 b. Other Historical Sources of International Law 33 c. The Age of Imperialism 34 d. The Consequences of World War II 35 i. The End of European Dominance 35 ii. Decolonization 35 iii. The Trials of Major War Criminals 35 iv. Human Rights Law 36 v.