Monograph 19: the Role of the Media in Promoting and Reducing Tobacco

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Sep 19 New Tobacco Products.Ppt

9/20/13 New Products Old Tricks The Problem What’s the Problem with New Products? New tobacco products are designed to: – Draw in new and youth users – Keep smokers smoking – Circumvent regulations and taxation 1 9/20/13 Increased youth smokeless tobacco use TOLL OF OTHER TOBACCO USE National Youth Smoking and Smokeless Tobacco Use 1997 - 2011 2003-2009: -11.0% 2003-2011: -17.4% 2003-2009: -9.2% 2003-2011: -8.7% 2003-2009: +36.4% 2003-2011: +16.4% 2003-2009: +32.8% 2003-2011: +14.9% Source: CDC, Youth Risk Behavior Surveillance Survey. 2 9/20/13 Most popular snuff brands among 12-17 year olds 1999-2011 2011 Top 3 Most Popular Moist Snuff Brands among 12-17 year olds 1. Grizzly (Reynolds American, via American Snuff Company) 2. Skoal (Altria, via UST) 3. Copenhagen (Altria, via UST) Source: 2011 NSDUH Source: Analysis of NHSDA, NSDUH data Health Harms of Other Tobacco Use Smokeless Tobacco It [smokeless • Cancer, including oral cancer tobacco] is not a safe and pancreatic cancer substitute for smoking cigarettes. • Gum disease -- U.S. Surgeon General, 1986 • Nicotine addiction Cigar Use • Cancer of the oral cavity, larynx, esophagus and lung 3 9/20/13 Brand development, Acquisitions Over Time WHERE IS THE INDUSTRY HEADED? Companies under in 1989 ( ) 4 9/20/13 Companies under in 2013 (28.5% economic interest) Tobacco Brands in 2013 Non-Tobacco Products 5 9/20/13 Companies under RJR Nabisco in 1989 Companies under in 2013 (formerly Conwood Company) B&W no longer exists as a separate company. -

Ritz-Carlton Half Moon Bay, Ca

RITZ-CARLTON HALF MOON BAY, CA APRIL 23-25, 2017 CLICK HERE TO DOWNLOAD PDF TABLE OF CONTENTS 2017 Value Program Members .......................................................... 3 Gold Value Program Members ...................................................... 4 Silver Value Program Members ................................................... 13 Bronze Value Program Members ................................................ 18 Agenda................................................................................................. 29 Hotel Map ........................................................................................... 32 Speaker Biographies ......................................................................... 33 Attendees ............................................................................................ 42 By Name ......................................................................................... 42 By Company ................................................................................... 45 Meeting Dates .................................................................................... 48 Board of Directors ............................................................................. 50 Current Data ....................................................................................... 53 SVIA Annual Investment and Policy Survey for 2016 ................ 53 SVIA Quarterly Characteristics Survey through 4Q2016 .......... 73 Stable Times Volume 20 Issue 2 ..................................................... -

Altria.Com/Proxy

6601 West Broad Street Richmond, Virginia 23230 Dear Fellow Shareholder: It is my pleasure to invite you to join us at the 2016 Annual Meeting of Shareholders of Altria Group, Inc. to be held on Thursday, May 19, 2016 at 9:00 a.m., Eastern Time, at the Greater Richmond Convention Center, 403 North 3rd Street, Richmond, Virginia 23219. At this year’s meeting, we will vote on the election of 11 directors, the ratification of the selection of PricewaterhouseCoopers LLP as the Company’s independent registered public accounting firm and, if properly presented, two shareholder proposals. We will also conduct a non-binding advisory vote to approve the compensation of the Company’s named executive officers. There also will be a report on the Company’s business, and shareholders will have an opportunity to ask questions. To attend the meeting, an admission ticket and government-issued photo identification are required. To request an admission ticket, please follow the instructions on page 9 in response to Question 16. One immediate family member who is 21 years of age or older may accompany a shareholder as a guest. We use the U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission rule that allows companies to furnish proxy materials to their shareholders over the Internet. We believe this expedites shareholders receiving proxy materials, lowers costs and conserves natural resources. We thus are mailing to many shareholders a Notice of Internet Availability of Proxy Materials, rather than a paper copy of the Proxy Statement and our Annual Report on Form 10-K for the fiscal year ended December 31, 2015. -

Altria Group, Inc. Annual Report

ananan Altria Altria Altria Company Company Company an Altria Company ananan Altria Altria Altria Company Company Company | Inc. Altria Group, Report 2020 Annual an Altria Company From tobacco company To tobacco harm reduction company ananan Altria Altria Altria Company Company Company an Altria Company ananan Altria Altria Altria Company Company Company an Altria Company Altria Group, Inc. Altria Group, Inc. | 6601 W. Broad Street | Richmond, VA 23230-1723 | altria.com 2020 Annual Report Altria 2020 Annual Report | Andra Design Studio | Tuesday, February 2, 2021 9:00am Altria 2020 Annual Report | Andra Design Studio | Tuesday, February 2, 2021 9:00am Dear Fellow Shareholders March 11, 2021 Altria delivered outstanding results in 2020 and made steady progress toward our 10-Year Vision (Vision) despite the many challenges we faced. Our tobacco businesses were resilient and our employees rose to the challenge together to navigate the COVID-19 pandemic, political and social unrest, and an uncertain economic outlook. Altria’s full-year adjusted diluted earnings per share (EPS) grew 3.6% driven primarily by strong performance of our tobacco businesses, and we increased our dividend for the 55th time in 51 years. Moving Beyond Smoking: Progress Toward Our 10-Year Vision Building on our long history of industry leadership, our Vision is to responsibly lead the transition of adult smokers to a non-combustible future. Altria is Moving Beyond Smoking and leading the way by taking actions to transition millions to potentially less harmful choices — a substantial opportunity for adult tobacco consumers 21+, Altria’s businesses, and society. To achieve our Vision, we are building a deep understanding of evolving adult tobacco consumer preferences, expanding awareness and availability of our non-combustible portfolio, and, when authorized by FDA, educating adult smokers about the benefits of switching to alternative products. -

Tobacco Product Use and Associated Factors Among Middle and High School Students — United States, 2019

Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report Surveillance Summaries / Vol. 68 / No. 12 December 6, 2019 Tobacco Product Use and Associated Factors Among Middle and High School Students — United States, 2019 U.S. Department of Health and Human Services Centers for Disease Control and Prevention Surveillance Summaries CONTENTS Introduction ............................................................................................................2 Methods ....................................................................................................................2 Results .......................................................................................................................5 Discussion ................................................................................................................8 Limitations ...............................................................................................................9 Conclusion ............................................................................................................ 10 References ............................................................................................................. 10 The MMWR series of publications is published by the Center for Surveillance, Epidemiology, and Laboratory Services, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Atlanta, GA 30329-4027. Suggested citation: [Author names; first three, then et al., if more than six.] [Title]. MMWR Surveill Summ 2019;68(No. SS-#):[inclusive -

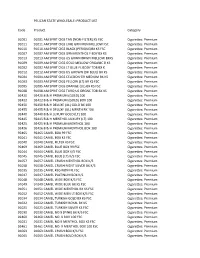

(NON-FILTER) KS FSC Cigarettes: Premiu

PELICAN STATE WHOLESALE: PRODUCT LIST Code Product Category 91001 91001 AM SPRIT CIGS TAN (NON‐FILTER) KS FSC Cigarettes: Premium 91011 91011 AM SPRIT CIGS LIME GRN MEN MELLOW FSC Cigarettes: Premium 91010 91010 AM SPRIT CIGS BLACK (PERIQUE)BX KS FSC Cigarettes: Premium 91007 91007 AM SPRIT CIGS GRN MENTHOL F BDY BX KS Cigarettes: Premium 91013 91013 AM SPRIT CIGS US GRWN BRWN MELLOW BXKS Cigarettes: Premium 91009 91009 AM SPRIT CIGS GOLD MELLOW ORGANIC B KS Cigarettes: Premium 91002 91002 AM SPRIT CIGS LT BLUE FL BODY TOB BX K Cigarettes: Premium 91012 91012 AM SPRIT CIGS US GROWN (DK BLUE) BX KS Cigarettes: Premium 91004 91004 AM SPRIT CIGS CELEDON GR MEDIUM BX KS Cigarettes: Premium 91003 91003 AM SPRIT CIGS YELLOW (LT) BX KS FSC Cigarettes: Premium 91005 91005 AM SPRIT CIGS ORANGE (UL) BX KS FSC Cigarettes: Premium 91008 91008 AM SPRIT CIGS TURQ US ORGNC TOB BX KS Cigarettes: Premium 92420 92420 B & H PREMIUM (GOLD) 100 Cigarettes: Premium 92422 92422 B & H PREMIUM (GOLD) BOX 100 Cigarettes: Premium 92450 92450 B & H DELUXE (UL) GOLD BX 100 Cigarettes: Premium 92455 92455 B & H DELUXE (UL) MENTH BX 100 Cigarettes: Premium 92440 92440 B & H LUXURY GOLD (LT) 100 Cigarettes: Premium 92445 92445 B & H MENTHOL LUXURY (LT) 100 Cigarettes: Premium 92425 92425 B & H PREMIUM MENTHOL 100 Cigarettes: Premium 92426 92426 B & H PREMIUM MENTHOL BOX 100 Cigarettes: Premium 92465 92465 CAMEL BOX 99 FSC Cigarettes: Premium 91041 91041 CAMEL BOX KS FSC Cigarettes: Premium 91040 91040 CAMEL FILTER KS FSC Cigarettes: Premium 92469 92469 CAMEL BLUE BOX -

Presidents Corner Using Intermediaries

INTERNATIONAL NETWORK OF WOMEN AGAINST TOBACCO Cancellation of the Foundation for a Smoke-Free World meeting Professor Elif Dagli | Chair Health Institute Association In the beginning of June 2019, tobacco control advocates, academicians, hospital physicians, tobacco leaf experts, economists, and some civil servants of Turkey, received an invitation to a full-day meeting titled “Istanbul Dialogues” organized by “Sustainability”. The objective of the meeting was to inform the stakeholders about the creation of a Smoke-Free Index by the Foundation for a Smoke-Free World (FSFW). The index was presented as a tool to transform the industry to eliminate combustible cigarettes and the diseases they cause (1). Against the Framework Convention on Tobacco Control (FCTC), article 5.3., the aim was to get the tobacco control community to meet together with representatives of the industry. The possibility of FSFW organizing a meeting in Istanbul on 3rd July 2019 created a state of emergency in the public health community. The tobacco industry was trying to sit down with civil servants and physicians around a table to discuss the future of their products Presidents Corner using intermediaries. It would be openly against FCTC if the industry had invited physicians directly. Marion Hale | President The innovative strategy of the industry was to put threePresidents levels of mediators in betweenCorner and give Cancellationthe Hello Again to all our INWAT supporters!of the trendy name “Istanbul Dialogues” to the meeting. This issue of The NET is a bumper issue themed around FoundationThe invitations were sent out by thefor “Sustainability a Smokethe tobacco industry’s-Free innovative strategiesWorld to target Academy” of Turkey on behalf of the parent company women and girls. -

Alaska Native Adult Tobacco Survey Member List Version

APPENDIX K: SURVEY (MEMBER LIST VERSION) |___|___|___|___| |___| |___|___| |___|___|___|___| |___|___|___|___| Year Interview Interviewer Survey Number Respondent ID Supervisor Alaska Native Adult Tobacco Survey Member List Version TABLE OF CONTENTS Section Page 1. Introduction ............................................................................................. 2 2. General Health .......................................................................................... 5 3. Cigarette Use ............................................................................................ 5 4. Iqmik Use ............................................................................................... 14 5. Chewing Tobacco (Spit) .......................................................................... 23 6. Snuff or Dip Tobacco .............................................................................. 32 7. Secondhand Smoke Exposure ................................................................. 42 8. Risk Perception ...................................................................................... 44 9. Demographics......................................................................................... 48 10. User-Selected Items ............................................................................. 52 Public burden of this collection of information is estimated to average 40 minutes per response, including the time for reviewing instructions, searching existing data sources, gathering and maintaining the data needed, -

Alameda County Tobacco Retailer License & Flavored Tobacco Training

ALAMEDA COUNTY TOBACCO RETAILER LICENSE & FLAVORED TOBACCO PRESENTATION 7/29/20 Providing Education and Support to Tobacco Retailers in Alameda County Agenda ❑ Welcome/Introductions ❑ Zoom Housekeeping ❑ Why Tobacco Retail Regulations? ❑ Alameda County’s Tobacco Retail Licensing Ordinance ❑ Restricted Tobacco Products ❑ Questionable Products ❑ Tobacco Retailer License Application Process ❑ Q & A WHY TOBACCO RETAIL REGULATIONS? Flavored Tobacco Hooks Kids Over 90% of adult smokers started before age 18 Flavored tobacco initiates youth tobacco use 4 out of 5 youth smokers started with a flavored product Adolescents are more likely than adults to use flavored e-cigs Fruit and candy flavors are designed to appeal to youth users by masking the harsh taste of tobacco Strong Tobacco Retail Licensing ordinances are effective at decreasing youth tobacco sales rates ALAMEDA COUNTY’S TOBACCO RETAILER LICENSING (TRL) ORDINANCE Overview of Adopted TRL Ordinance Purpose is to reduce youth access to tobacco, and to limit negative public health effects of tobacco use. Requires businesses in Unincorporated Alameda County that sell tobacco to obtain a local license annually to sell tobacco. Provides enforcement mechanism; holds retailers accountable to comply with local requirements, as well as state and federal tobacco laws. Overview of Adopted TRL Ordinance TRL ordinance adopted by BOS on January 14, 2020 Electronic Smoking Devices adopted by BOS on March 10, 2020 Retailers obtain TRL by August 7, 2020 Enforcement of both laws begin: September -

Towardatobaccofreeworld Hi Res.Pdf

Toward A Tobacco Free World Preface This e-book Toward A Tobacco Free World is being given away to inform people about the significant adverse effect tobacco continues to have on humanity. It’s also being given away to create awareness of the World Health Organization’s World No Tobacco Day on May 31st. According to the World Health Organization, 1 billion people will die from smoking in this century. This dire scenario doesn’t have to hap- pen. The time is NOW to act as a community in preventing children and teens from starting to use tobacco products and helping those who want to quit. The Good News and the Bad News Since the printed version of Toward A Tobacco Free World came out at the end of 2006 (Ending The Tobacco Holocaust), the U.S. has expe- rienced a decrease in tobacco smoking as well as a decrease in overall exposure to second-hand smoke. That’s the good news. Specifically, the percentage of adults who smoke has dropped from 20.8 % to 19.8 %, and the percentage of high school seniors who smoked in the last 30 days has dropped from 21.6% to 20.4%. However, the bad news is that 19.8 % of adults and 20.4 % of high school seniors in the U.S. still smoke. The U.S. government’s Healthy People 2010 goals called for only 12% of adults, and 16% of adolescents, to smoke by 2010. It IS a Big Deal Interestingly, when asked, many Americans don’t regard the tobacco problem as a big issue. -

At Work in the World

Perspectives in Medical Humanities At Work in the World Proceedings of the Fourth International Conference on the History of Occupational and Environmental Health Edited by Paul D. Blanc, MD and Brian Dolan, PhD Page Intentionally Left Blank At Work in the World Proceedings of the Fourth International Conference on the History of Occupational and Environmental Health Perspectives in Medical Humanities Perspectives in Medical Humanities publishes scholarship produced or reviewed under the auspices of the University of California Medical Humanities Consortium, a multi-campus collaborative of faculty, students and trainees in the humanities, medi- cine, and health sciences. Our series invites scholars from the humanities and health care professions to share narratives and analysis on health, healing, and the contexts of our beliefs and practices that impact biomedical inquiry. General Editor Brian Dolan, PhD, Professor of Social Medicine and Medical Humanities, University of California, San Francisco (ucsf) Recent Monograph Titles Health Citizenship: Essays in Social Medicine and Biomedical Politics By Dorothy Porter (Fall 2011) Paths to Innovation: Discovering Recombinant DNA, Oncogenes and Prions, In One Medical School, Over One Decade By Henry Bourne (Fall 2011) The Remarkables: Endocrine Abnormalities in Art By Carol Clark and Orlo Clark (Winter 2011) Clowns and Jokers Can Heal Us: Comedy and Medicine By Albert Howard Carter iii (Winter 2011) www.medicalhumanities.ucsf.edu [email protected] This series is made possible by the generous support of the Dean of the School of Medicine at ucsf, the Center for Humanities and Health Sciences at ucsf, and a Multi-Campus Research Program grant from the University of California Office of the President. -

Menthol Marketing to the LGBTQ Community

MENTHOL GET THE FACTS Menthol makes smoking easier to start and harder to quit. Evidence from tobacco industry documents shows that the industry studied smokers’ menthol preferences and manipulated menthol levels to appeal to adolescents and young adults. African Americans smoke 3 TIMES MORE menthol than whites so target marketing makes quitting harder. Studies show that amounts of tar, nicotine and other poisons are 30 -70% higher in inhaled menthol cigarettes than in non-mentholated cigarettes. The Surgeon General has stated that people who smoke menthols inhale more deeply and keep the smoke in their lungs longer, which gives them greater exposure to the 4,000 chemicals and poisons in cigarettes. A menthol ban could save 340,000 lives, over 100,000 black lives by 2050. @CityofMilwaukeeTobaccoFreeAlliance @WAATPN @MKETobaccoFree @WAATPN Source © 2016 NAATPN, Inc. All rights reserved. Menthol Marketing to the LGBTQ Community LGBTQ youth and adults smoke at higher rates than the general population due to industry targeting, social norms centered around bar culture, and minority stress, including lack of family acceptance. Did you know… In the 90s, a tobacco company created a marketing plan targeting gay people in San Francisco. They called it Project SCUM. Marketing For decades, the tobacco industry has targeted African Americans, women, youth, and the LGBTQ community with menthol marketing through advertisements and music events. More recently, tobacco companies have targeted menthol marketing to traditionally safe spaces for the LGBTQ community, like bars and Pride festivals, through event sponsorship and coupons to buy packs for $1. Ad from Out Magazine (2001) promoting Ad from Out Magazine, 1994 the “House of Menthol.” “Houses” have long been a form of LGBTQ social support and entertainment to ll a void when families of origin are unsupportive.