The Czech Republic and Romania; It's Time to Change the Rules Susan Meyer

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Tobacco Deal Sealed Prior to Global Finance Market Going up in Smoke

marketwatch KEY DEALS Tobacco deal sealed prior to global finance market going up in smoke The global credit crunch which so rocked £5.4bn bridging loan with ABN Amro, Morgan deal. “It had become an auction involving one or Iinternational capital markets this summer Stanley, Citigroup and Lehman Brothers. more possible white knights,” he said. is likely to lead to a long tail of negotiated and In addition it is rescheduling £9.2bn of debt – Elliott said the deal would be part-funded by renegotiated deals and debt issues long into both its existing commitments and that sitting on a large-scale disposal of Rio Tinto assets worth the autumn. the balance sheet of Altadis – through a new as much as $10bn. Rio’s diamonds, gold and But the manifestation of a bad bout of the facility to be arranged by Citigroup, Royal Bank of industrial minerals businesses are now wobbles was preceded by some of the Scotland, Lehmans, Barclays and Banco Santander. reckoned to be favourites to be sold. megadeals that the equity market had been Finance Director Bob Dyrbus said: Financing the deal will be new underwritten expecting for much of the last two years. “Refinancing of the facilities is the start of a facilities provided by Royal Bank of Scotland, One such long awaited deal was the e16.2bn process that is not expected to complete until the Deutsche Bank, Credit Suisse and Société takeover of Altadis by Imperial Tobacco. first quarter of the next financial year. Générale, while Deutsche and CIBC are acting as Strategically the Imps acquisition of Altadis “Imperial Tobacco only does deals that can principal advisors on the deal with the help of has been seen as the must-do in a global generate great returns for our shareholders and Credit Suisse and Rothschild. -

The Romanization of Romania: a Look at the Influence of the Roman Military on Romanian History and Heritage Colleen Ann Lovely Union College - Schenectady, NY

Union College Union | Digital Works Honors Theses Student Work 6-2016 The Romanization of Romania: A Look at the Influence of the Roman Military on Romanian History and Heritage Colleen Ann Lovely Union College - Schenectady, NY Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalworks.union.edu/theses Part of the Ancient History, Greek and Roman through Late Antiquity Commons, European History Commons, and the Military History Commons Recommended Citation Lovely, Colleen Ann, "The Romanization of Romania: A Look at the Influence of the Roman Military on Romanian History and Heritage" (2016). Honors Theses. 178. https://digitalworks.union.edu/theses/178 This Open Access is brought to you for free and open access by the Student Work at Union | Digital Works. It has been accepted for inclusion in Honors Theses by an authorized administrator of Union | Digital Works. For more information, please contact [email protected]. The Romanization of Romania: A Look at the Influence of the Roman Military on Romanian History and Heritage By Colleen Ann Lovely ********* Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for Honors in the Departments of Classics and Anthropology UNION COLLEGE March 2016 Abstract LOVELY, COLLEEN ANN The Romanization of Romania: A Look at the Influence of the Roman Military on Romanian History and Heritage. Departments of Classics and Anthropology, March 2016. ADVISORS: Professor Stacie Raucci, Professor Robert Samet This thesis looks at the Roman military and how it was the driving force which spread Roman culture. The Roman military stabilized regions, providing protection and security for regions to develop culturally and economically. Roman soldiers brought with them their native cultures, languages, and religions, which spread through their interactions and connections with local peoples and the communities in which they were stationed. -

C O N V E N T I O N Between the Hellenic Republic and Romania For

CONVENTION between the Hellenic Republic and Romania for the avoidance of double taxation with respect to taxes on income and on capital. The Government of the Hellenic Republic and the Government of Romania Desiring to promote and strengthen the economic relations between the two countries on the basis of national sovereignty and respect of independence, equality in rights, reciprocal advantage and non-interference in domestic matters; have agreed as follows: Article 1 PERSONAL SCOPE This Convention shall apply to persons who are residents of one or both of the Contracting States. Article 2 TAXES COVERED 1. This Convention shall apply to taxes on income and on capital imposed on behalf of a Contracting State or of its administrative territorial units or local authorities, irrespective of the manner in which they are levied. 2. There shall be regarded as taxes on income and on capital all taxes imposed on total income, on total capital, or on elements of income or of capital, including taxes on gains from the alienation of movable or immovable property, as well as taxes on capital appreciation. 3. The existing taxes to which the Convention shall apply are in particular: a) In the case of the Hellenic Republic: i) the income and capital tax on natural persons ; ii) the income and capital tax on legal persons; iii) the contribution for the Water Supply and Drainage Agencies calculated on the gross- income from buildings; (hereinafter referred to as "(Hellenic tax"). b) In the case of Romania: i) the individual income tax; ii) the tax on salaries, wages and other similar remunerations ; iii) the tax on the profits; iv) the tax on income realised by individuals from agricultural activities; hereinafter referred to as "Romania tax"). -

Mixed Migration Flows in the Mediterranean Compilation of Available Data and Information April 2017

MIXED MIGRATION FLOWS IN THE MEDITERRANEAN COMPILATION OF AVAILABLE DATA AND INFORMATION APRIL 2017 TOTAL ARRIVALS TOTAL ARRIVALS TOTAL ARRIVALS 46,015 TO EUROPE 45,056 TO EUROPE BY SEA 959 TO EUROPE BY LAND Content Highlights • Cummulative Arrivals and Weekly Overview According to available data, there have been 46,015 new arrivals to Greece, Italy, Bulgaria, Cyprus and Spain between 1 January and 30 April • Overview Maps 2017. • EU-Turkey Statement Overview Until 30 April 2017, there were estimated 37,248 cumulative arrivals to • Relocations Italy, compared to 27,926 arrivals recorded at the end of the same month • Bulgaria in 2016 (33% increase). Contrary to that, Greece has seen a 96% lower number of arrivals by the end April 2017 when compared to the same • Croatia period 2016 (5,742 and 156,551 respectively). • Cyprus At the end of April, total number of migrants and refugees stranded in • Greece Greece, Cyprus and in the Western Balkans reached 73,900. Since the im- • Hungary plementation of the EU-Turkey Statement on 18 March 2016, the number • Italy of migrants stranded in Greece increased by 45%. More information could be found on page 5. • Romania • Serbia Between October 2015 and 30 April 2017, 17,909 individuals have been relocated to 24 European countries. Please see page on relocations for • Slovenia more information. • Turkey In the first four months of 2017, total of 1,093 migrants and refugees • The former Yugoslav Republic of were readmitted from Greece to Turkey as part of the EU-Turkey State- Macedonia ment. The majority of migrants and refugees were Pakistani, Syrian, Alge- • Central Mediterranean rian, Afghan, and Bangladeshi nationals (more info inTurkey section). -

Ritz-Carlton Half Moon Bay, Ca

RITZ-CARLTON HALF MOON BAY, CA APRIL 23-25, 2017 CLICK HERE TO DOWNLOAD PDF TABLE OF CONTENTS 2017 Value Program Members .......................................................... 3 Gold Value Program Members ...................................................... 4 Silver Value Program Members ................................................... 13 Bronze Value Program Members ................................................ 18 Agenda................................................................................................. 29 Hotel Map ........................................................................................... 32 Speaker Biographies ......................................................................... 33 Attendees ............................................................................................ 42 By Name ......................................................................................... 42 By Company ................................................................................... 45 Meeting Dates .................................................................................... 48 Board of Directors ............................................................................. 50 Current Data ....................................................................................... 53 SVIA Annual Investment and Policy Survey for 2016 ................ 53 SVIA Quarterly Characteristics Survey through 4Q2016 .......... 73 Stable Times Volume 20 Issue 2 ..................................................... -

Accelerated Lignite Exit in Bulgaria, Romania and Greece

Accelerated lignite exit in Bulgaria, Romania and Greece May 2020 Report: Accelerated lignite exit in Bulgaria, Romania and Greece Authors: REKK: Dr. László Szabó, Dr. András Mezősi, Enikő Kácsor (chapters 1, 2, 3, 4 and 5) TU Wien: Dr. Gustav Resch, Lukas Liebmann (chapters 2, 3, 4 and 5) CSD: Martin Vladimirov, Dr. Todor Galev, Dr. Radostina Primova (chapter 3) EPG: Dr. Radu Dudău, Mihnea Cătuți, Andrei Covatariu, Dr. Mihai Bălan (chapter 5) FACETS: Dr. Dimitri Lalas, Nikos Gakis (chapter 4) External Experts: Csaba Vaszkó, Alexandru Mustață (chapters 2.4, 3.2, 4.2 and 5.2) 2 The Regional Centre for Energy Policy Research (REKK) is a Budapest based think tank. The aim of REKK is to provide professional analysis and advice on networked energy markets that are both commercially and environmentally sustainable. REKK has performed comprehensive research, consulting and teaching activities in the fields of electricity, gas and carbon-dioxide markets since 2004, with analyses ranging from the impact assessments of regulatory measures to the preparation of individual companies' investment decisions. The Energy Economics Group (EEG), part of the Institute of Energy Systems and Electrical Drives at the Technische Universität Wien (TU Wien), conducts research in the core areas of renewable energy, energy modelling, sustainable energy systems, and energy markets. EEG has managed and carried out many international as well as national research projects funded by the European Commission, national governments, public and private clients in several fields of research, especially focusing on renewable- and new energy systems. EEG is based in Vienna and was originally founded as research institute at TU Wien. -

Appendix 1. Categorization of Cigarette Brands As Either Premium Or Discount

Appendix 1. Categorization of Cigarette Brands as either Premium or Discount Category Name of Cigarette Brand Premium Accord, American Spirit, Barclay, Belair, Benson & Hedges, Camel, Capri, Carlton, Chesterfield, Davidoff, Du Maurier, Dunhill, Dunhill International, Eve, Kent, Kool, L&M, Lark, Lucky Strike, Marlboro, Max, Merit, Mild Seven, More, Nat Sherman, Newport, Now, Parliament, Players, Quest, Rothman’s, Salem, Sampoerna, Saratoga, Tareyton, True, Vantage, Virginia Slims, Winston, Raleigh, Business Club Full Flavor, Ronhill, Dreams Discount 24/7, 305, 1839, A1, Ace, Allstar, Allway Save, Alpine, American, American Diamond, American Hero, American Liberty, Arrow, Austin, Axis, Baileys, Bargain Buy, Baron, Basic, Beacon, Berkeley, Best Value, Black Hawk, Bonus Value, Boston, Bracar, Brand X, Brave, Brentwood, Bridgeport, Bronco, Bronson, Bucks, Buffalo, BV, Calon, Cambridge, Campton, Cannon, Cardinal, Carnival, Cavalier, Champion, Charter, Checkers, Cherokee, Cheyenne, Cimarron, Circle Z, Class A, Classic, Cobra, Complete, Corona, Courier, CT, Decade, Desert Gold, Desert Sun, Discount, Doral, Double Diamond, DTC, Durant, Eagle, Echo, Edgefield, Epic, Esquire, Euro, Exact, Exeter, First Choice, First Class, Focus, Fortuna, Galaxy Pro, Gauloises, Generals, Generic/Private Label, Geronimo, Gold Coast, Gold Crest, Golden Bay, Golden, Golden Beach, Golden Palace, GP, GPC, Grand, Grand Prix, G Smoke, GT Ones, Hava Club, HB, Heron, Highway, Hi-Val, Jacks, Jade, Kentucky Best, King Mountain, Kingsley, Kingston, Kingsport, Knife, Knights, -

Romania, December 2006

Library of Congress – Federal Research Division Country Profile: Romania, December 2006 COUNTRY PROFILE: ROMANIA December 2006 COUNTRY Formal Name: Romania. Short Form: Romania. Term for Citizen(s): Romanian(s). Capital: Bucharest (Bucureşti). Click to Enlarge Image Major Cities: As of 2003, Bucharest is the largest city in Romania, with 1.93 million inhabitants. Other major cities, in order of population, are Iaşi (313,444), Constanţa (309,965), Timişoara (308,019), Craiova (300,843), Galati (300,211), Cluj-Napoca (294,906), Braşov (286,371), and Ploeşti (236,724). Independence: July 13, 1878, from the Ottoman Empire; kingdom proclaimed March 26, 1881; Romanian People’s Republic proclaimed April 13, 1948. Public Holidays: Romania observes the following public holidays: New Year’s Day (January 1), Epiphany (January 6), Orthodox Easter (a variable date in April or early May), Labor Day (May 1), Unification Day (December 1), and National Day and Christmas (December 25). Flag: The Romanian flag has three equal vertical stripes of blue (left), yellow, and red. Click to Enlarge Image HISTORICAL BACKGROUND Early Human Settlement: Human settlement first occurred in the lands that now constitute Romania during the Pleistocene Epoch, which began about 600,000 years ago. About 5500 B.C. the region was inhabited by Indo-European people, who in turn gave way to Thracian tribes. Today’s Romanians are in part descended from the Getae, a Thracian tribe that lived north of the Danube River. During the Bronze Age (about 2200 to 1200 B.C.), these Thraco-Getian tribes engaged in agriculture, stock raising, and trade with inhabitants of the Aegean Sea coast. -

1 CO-OPERATION AGREEMENT Dated As of 27 September 2010

CO-OPERATION AGREEMENT dated as of 27 September 2010 among IMPERIAL TOBACCO LIMITED AND THE EUROPEAN UNION REPRESENTED BY THE EUROPEAN COMMISSION AND EACH MEMBER STATE LISTED ON THE SIGNATURE PAGES HERETO 1 ARTICLE 1 DEFINITIONS Section 1.1. Definitions........................................................................................... 7 ARTICLE 2 ITL’S SALES AND DISTRIBUTION COMPLIANCE PRACTICES Section 2.1. ITL Policies and Code of Conduct.................................................... 12 Section 2.2. Certification of Compliance.............................................................. 12 Section 2.3 Acquisition of Other Tobacco Companies and New Manufacturing Facilities. .......................................................................................... 14 Section 2.4 Subsequent changes to Affiliates of ITL............................................ 14 ARTICLE 3 ANTI-CONTRABAND AND ANTI-COUNTERFEIT INITIATIVES Section 3.1. Anti-Contraband and Anti-Counterfeit Initiatives............................ 14 Section 3.2. Support for Anti-Contraband and Anti-Counterfeit Initiatives......... 14 ARTICLE 4 PAYMENTS TO SUPPORT THE ANTI-CONTRABAND AND ANTI-COUNTERFEIT COOPERATION ARTICLE 5 NOTIFICATION AND INSPECTION OF CONTRABAND AND COUNTERFEIT SEIZURES Section 5.1. Notice of Seizure. .............................................................................. 15 Section 5.2. Inspection of Seizures. ...................................................................... 16 Section 5.3. Determination of Seizures................................................................ -

OTP Wholesalers September 28, 2021

OTP Wholesalers September 28, 2021 Owner Information Business Information Permit Number 4700114 A & E WHOLESALE OF NORTH FLORIDA, LLC A & E WHOLESALE OF NORTH FLORIDA, LLC POST OFFICE BOX 21 1023 CAPITAL CIRCLE NW TALLAHASSEE, FL 32302 TALLAHASSEE, FL 32304 Permit Number 6200236 A & J DISTRIBUTING CORP A & J DISTRIBUTING CORP 3880 69TH AVE 3880 69TH AVE PINELLAS PARK, FL 33781 PINELLAS PARK, FL 33781 Permit Number 5800250 ABC LIQUORS INC ABC LIQUORS INC PO BOX 593688 8989 SOUTH ORANGE AVENUE ORLANDO, FL 32859-3688 ORLANDO, FL 32824 Permit Number 2600353 ADEL WHOLESALE ADEL WHOLESALE 2500 CHARLEVOIX ST 2500 CHARLEVOIX ST JACKSONVILLE, FL 32206 JACKSONVILLE, FL 32206 Permit Number 3900610 ALFA DISTRIBUTING INC ALFA DISTRIBUTING INC 18103 REGENTS SQ DRIVE 18103 REGENTS SQ DRIVE TAMPA, FL 33647 TAMPA, FL 33647 Permit Number 3900605 ALKEIF COFFEE & SMOKE SHOP ALKEIF COFFEE & SMOKE SHOP 4815 E. BUSCH BLVD. 110 BUTLER RD SUITE 103 BRANDON, FL 33511 TAMPA, FL 33617 Permit Number 7900040 ALTADIS U.S.A., INC. ALTADIS U.S.A., INC. 5900 N ANDREWS AVE 600 PERDUE AVENUE FORT LAUDERDALE, FL 33309 RICHMOND, VA 23224 Permit Number 3900405 ALTADIS USA INC ALTADIS USA INC 5900 N ANDREWS AVE 2601 H. TAMPA EAST BLVD FORT LAUDERDALE, FL 33309 TAMPA, FL 33619 Page 1 of 27 OTP Wholesalers September 28, 2021 Owner Information Business Information Permit Number 3900598 AMERICAN COMMERCIAL GROUP LLC AMERICAN COMMERCIAL GROUP LLC 12634 NICOLE LN 5705 HANNA AVE TAMPA, FL 33625 TAMPA, FL 33610 Permit Number 7900073 ANDALUSIA DISTRIBUTING CO INC ANDALUSIA DISTRIBUTING CO INC P O BOX 51 115 ALLEN AVE ANDALUSIA, AL 36420 ANDALUSIA, AL 36420 Permit Number 1614252 ASSOCIATED GROCERS OF FLORIDA INC ASSOCIATED GROCERS OF FLORIDA INC 1141 SW 12TH AVE 1141 SW 12TH AVE POMPANO BEACH, FL 33069 POMPANO BEACH, FL 33069 Permit Number 7900030 ATLANTIC DOMINION DISTRIBUTORS ATLANTIC DOMINION DISTRIBUTORS P.O. -

Directory of Fire Safe Certified Cigarette Brand Styles Updated 11/20/09

Directory of Fire Safe Certified Cigarette Brand Styles Updated 11/20/09 Beginning August 1, 2008, only the cigarette brands and styles listed below are allowed to be imported, stamped and/or sold in the State of Alaska. Per AS 18.74, these brands must be marked as fire safe on the packaging. The brand styles listed below have been certified as fire safe by the State Fire Marshall, bear the "FSC" marking. There is an exception to these requirements. The new fire safe law allows for the sale of cigarettes that are not fire safe and do not have the "FSC" marking as long as they were stamped and in the State of Alaska before August 1, 2008 and found on the "Directory of MSA Compliant Cigarette & RYO Brands." Filter/ Non- Brand Style Length Circ. Filter Pkg. Descr. Manufacturer 1839 Full Flavor 82.7 24.60 Filter Hard Pack U.S. Flue-Cured Tobacco Growers, Inc. 1839 Full Flavor 97 24.60 Filter Hard Pack U.S. Flue-Cured Tobacco Growers, Inc. 1839 Full Flavor 83 24.60 Non-Filter Soft Pack U.S. Flue-Cured Tobacco Growers, Inc. 1839 Light 83 24.40 Filter Hard Pack U.S. Flue-Cured Tobacco Growers, Inc. 1839 Light 97 24.50 Filter Hard Pack U.S. Flue-Cured Tobacco Growers, Inc. 1839 Menthol 97 24.50 Filter Hard Pack U.S. Flue-Cured Tobacco Growers, Inc. 1839 Menthol 83 24.60 Filter Hard Pack U.S. Flue-Cured Tobacco Growers, Inc. 1839 Menthol Light 83 24.50 Filter Hard Pack U.S. -

Cigarette Minimum Retail Price List

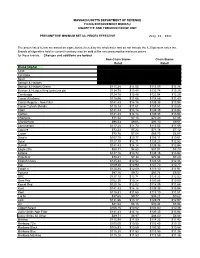

MASSACHUSETTS DEPARTMENT OF REVENUE FILING ENFORCEMENT BUREAU CIGARETTE AND TOBACCO EXCISE UNIT PRESUMPTIVE MINIMUM RETAIL PRICES EFFECTIVE July 26, 2021 The prices listed below are based on cigarettes delivered by the wholesaler and do not include the 6.25 percent sales tax. Brands of cigarettes held in current inventory may be sold at the new presumptive minimum prices for those brands. Changes and additions are bolded. Non-Chain Stores Chain Stores Retail Retail Brand (Alpha) Carton Pack Carton Pack 1839 $86.64 $8.66 $85.38 $8.54 1st Class $71.49 $7.15 $70.44 $7.04 Basic $122.21 $12.22 $120.41 $12.04 Benson & Hedges $136.55 $13.66 $134.54 $13.45 Benson & Hedges Green $115.28 $11.53 $113.59 $11.36 Benson & Hedges King (princess pk) $134.75 $13.48 $132.78 $13.28 Cambridge $124.78 $12.48 $122.94 $12.29 Camel All others $116.56 $11.66 $114.85 $11.49 Camel Regular - Non Filter $141.43 $14.14 $139.35 $13.94 Camel Turkish Blends $110.14 $11.01 $108.51 $10.85 Capri $141.43 $14.14 $139.35 $13.94 Carlton $141.43 $14.14 $139.35 $13.94 Checkers $71.54 $7.15 $70.49 $7.05 Chesterfield $96.53 $9.65 $95.10 $9.51 Commander $117.28 $11.73 $115.55 $11.56 Couture $72.23 $7.22 $71.16 $7.12 Crown $70.76 $7.08 $69.73 $6.97 Dave's $107.70 $10.77 $106.11 $10.61 Doral $127.10 $12.71 $125.23 $12.52 Dunhill $141.43 $14.14 $139.35 $13.94 Eagle 20's $88.31 $8.83 $87.01 $8.70 Eclipse $137.16 $13.72 $135.15 $13.52 Edgefield $73.41 $7.34 $72.34 $7.23 English Ovals $125.44 $12.54 $123.59 $12.36 Eve $109.30 $10.93 $107.70 $10.77 Export A $120.88 $12.09 $119.10 $11.91