Nest-Site Competition Between Adelie and Chinstrap Penguins: an Ecological Interpretation

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

A Global Population Assessment of the Chinstrap Penguin (Pygoscelis

www.nature.com/scientificreports OPEN A global population assessment of the Chinstrap penguin (Pygoscelis antarctica) Noah Strycker1*, Michael Wethington2, Alex Borowicz2, Steve Forrest2, Chandi Witharana3, Tom Hart4 & Heather J. Lynch2,5 Using satellite imagery, drone imagery, and ground counts, we have assembled the frst comprehensive global population assessment of Chinstrap penguins (Pygoscelis antarctica) at 3.42 (95th-percentile CI: [2.98, 4.00]) million breeding pairs across 375 extant colonies. Twenty-three previously known Chinstrap penguin colonies are found to be absent or extirpated. We identify fve new colonies, and 21 additional colonies previously unreported and likely missed by previous surveys. Limited or imprecise historical data prohibit our assessment of population change at 35% of all Chinstrap penguin colonies. Of colonies for which a comparison can be made to historical counts in the 1980s, 45% have probably or certainly declined and 18% have probably or certainly increased. Several large colonies in the South Sandwich Islands, where conditions apparently remain favorable for Chinstrap penguins, cannot be assessed against a historical benchmark. Our population assessment provides a detailed baseline for quantifying future changes in Chinstrap penguin abundance, sheds new light on the environmental drivers of Chinstrap penguin population dynamics in Antarctica, and contributes to ongoing monitoring and conservation eforts at a time of climate change and concerns over declining krill abundance in the Southern Ocean. Chinstrap penguins (Pygoscelis antarctica) are abundant in Antarctica, with past estimates ranging from 3–8 million breeding pairs, and are considered a species of “least concern” by BirdLife International1, but the popula- tion dynamics of this species are not well understood and several studies have highlighted signifcant declines at monitored sites2–6. -

Foraging Behavior of Gentoo and Chinstrap Penguins As Determined by New Radiotelemetry Techniques

FORAGING BEHAVIOR OF GENTOO AND CHINSTRAP PENGUINS AS DETERMINED BY NEW RADIOTELEMETRY TECHNIQUES WAYNE Z. TRIVELPIECE,JOHN L. BENGTSON,1 SUSAN G. TRIVELPIECE, AND NICHOLAS J. VOLKMAN PointReyes Bird Observatory, 4990 Shoreline Highway, Stinson Beach, California 94970 USA ASSTRACT.--Analysisof radio signalsfrom transmittersaffixed to 7 Gentoo(Pygoscelis papua) and 6 Chinstrap (P. antarctica)penguins allowed us to track penguins at sea. Signal charac- teristics allowed us to distinguish among 5 foraging behaviors: porpoising, underwater swimming, horizontal diving, vertical diving, and restingor bathing. GentooPenguins spent a significantly greater portion of their foraging trips engaged in feeding behaviors than Chinstraps,which spent significantly more time traveling. Gentooshad significantly longer feeding dives than Chinstraps(128 s vs. 91 s) and significantlyhigher dive-pauseratios (3.4 vs. 2.6). These differencesin foraging behavior suggestGentoo and Chinstrappenguins may have different diving abilities and may forage at different depths. Received3 June 1985, accepted24 April 1986. THE trophic relationships among Pygoscelis among behaviors during foraging trips. This penguins,the Ad61ie(P. adeliae),Chinstrap (P. method improved our understanding of pen- antarctica),and Gentoo (P. papua),have been a guin feeding efficiencies,ranges, and traveling major focal point of researchin recent years, speeds,and permitted preliminary compari- particularlywith respectto the ecologyof their sons of Gentoo and Chinstrap penguin forag- major prey species,krill (Euphausiasuperba). To ing behaviors. date, however, our knowledge of the birds' METHODS feeding ecologyis largely derived from stom- ach samples obtained ashore (Emison 1968; This studywas conductedat a breedingrookery at Croxall and Furse 1980; Croxall and Prince Point Thomas, King George Island, South Shetland 1980a;Volkman et al. -

Sentinels of the Ocean the Science of the World’S Penguins

A scientific report from The Pew Charitable Trusts April 2015 Sentinels Of the Ocean The science of the world’s penguins Contents 1 Overview 1 Status of penguin populations 1 Penguin biology Species 3 22 The Southern Ocean 24 Threats to penguins Fisheries 24 Increasing forage fisheries 24 Bycatch 24 Mismatch 24 Climate change 25 Habitat degradation and changes in land use 25 Petroleum pollution 25 Guano harvest 26 Erosion and loss of native plants 26 Tourism 26 Predation 26 Invasive predators 26 Native predators 27 Disease and toxins 27 27 Protecting penguins Marine protected areas 27 Ecosystem-based management 29 Ocean zoning 29 Habitat protections on land 30 31 Conclusion 32 References This report was written for Pew by: Pablo García Borboroglu, Ph.D., president, Global Penguin Society P. Dee Boersma, Ph.D., director, Center for Penguins as Ocean Sentinels, University of Washington Caroline Cappello, Center for Penguins as Ocean Sentinels, University of Washington Pew’s environmental initiative Joshua S. Reichert, executive vice president Tom Wathen, vice president Environmental science division Becky Goldburg, Ph.D., director, environmental science Rachel Brittin, officer, communications Polita Glynn, director, Pew Marine Fellows Program Ben Shouse, senior associate Charlotte Hudson, director, Lenfest Ocean Program Anthony Rogers, senior associate Katie Matthews, Ph.D., manager Katy Sater, senior associate Angela Bednarek, Ph.D., manager Acknowledgments The authors wish to thank the many contributors to Penguins: Natural History and Conservation (University of Washington Press, 2013), upon whose scholarship this report is based. Used by permission of the University of Washington Press The environmental science team would like to thank Dee Boersma, Pablo “Popi” Borboroglu, and Caroline Cappello for sharing their knowledge of penguins by writing and preparing this report. -

Foraging Behaviour of the Chinstrap Penguin 85

1999 Wilson & Peters: Foraging behaviour of the Chinstrap Penguin 85 FORAGING BEHAVIOUR OF THE CHINSTRAP PENGUIN PYGOSCELIS ANTARCTICA AT ARDLEY ISLAND, ANTARCTICA RORY P. WILSON & GERRIT PETERS Institut für Meereskunde an der Universität Kiel, Düsternbrooker Weg 20, D-24105 Kiel, Germany ([email protected]) SUMMARY WILSON, R.P. & PETERS, G. 1999. Foraging behaviour of the Chinstrap Penguin Pygoscelis antarctica at Ardley Island, Antarctica. Marine Ornithology 27: 85–95. The foraging behaviour of 20 Chinstrap Penguins Pygoscelis antarctica breeding at Ardley Island, King George Island, Antarctica was studied during the austral summers of 1991/2 and 1995/6 using stomach tem- perature loggers (to determine feeding patterns), depth recorders and multiple channel loggers. The multi- ple channel loggers recorded dive depth, swim speed and swim heading which could be integrated using vectors to determine the foraging tracks. Half the birds left the island to forage between 02h00 and 10h00. Mean time at sea was 10.6 h. Birds generally executed a looping type course with most individuals foraging within 20 km of the island. Maximum foraging range was 33.5 km. Maximum dive depth was 100.7 m although 80% of all dives had depth maxima less than 30 m. The following dive parameters were positively related to maximum depth reached during the dive: total dive duration, descent duration, duration at the bottom of the dive, ascent duration, descent angle, ascent angle, rate of change of depth during descent and rate of change of depth during ascent. Swim speed was unrelated to maximum dive depth and had mean values of 2.6, 2.5 and 2.2 m/s for the descent, bottom and ascent phases of the dive. -

Endangered Species Research 39:293

Vol. 39: 293–302, 2019 ENDANGERED SPECIES RESEARCH Published August 22 https://doi.org/10.3354/esr00970 Endang Species Res OPENPEN ACCESSCCESS Sexual and geographic dimorphism in northern rockhopper penguins breeding in the South Atlantic Ocean Antje Steinfurth1,2,*,**, Jenny M. Booth3,**, Jeff White4, Alexander L. Bond5,6, Christopher D. McQuaid3 1FitzPatrick Institute of African Ornithology, DST/NRF Centre of Excellence, University of Cape Town, Rondebosch 7700, South Africa 2RSPB Centre for Conservation Science, Royal Society for the Protection of Birds, David Attenborough Building, Cambridge, Cambridgeshire CB2 3QZ, UK 3Coastal Research Group, Department of Zoology and Entomology, Rhodes University, PO Box 94, Grahamstown 6140, South Africa 4Marshall University, Huntington, WV 25755, USA 5RSPB Centre for Conservation Science, Royal Society for the Protection of Birds, The Lodge, Sandy, Bedfordshire SG19 2DL, UK 6Bird Group, Department of Life Sciences, The Natural History Museum, Tring, Hertfordshire HP23 6AP, UK ABSTRACT: The Endangered northern rockhopper penguin Eudyptes moseleyi, like all pen- guins, is monomorphic, making sex determination of individuals in the field challenging. We examined the degree of sexual size dimorphism of adult birds across the species’ breeding range in the Atlantic Ocean and developed discriminant functions (DF) to predict individuals’ sex using morphometric measurements. We found significant site-specific differences in both bill length and bill depth, with males being the larger sex on each island. Across all islands, bill length contri - buted 78% to dissimilarity between sexes. Penguins on Gough Island had significantly longer bills, whilst those from Tristan da Cunha had the deepest. Island-specific DFs correctly classified 82−94% of individuals, and all functions performed significantly better than chance. -

Evolutionary and Ecological Aspects of Some Antarctic and Sub-Antarctic Penguin Distributions

Oecologia (2002) 130:485–495 DOI 10.1007/s00442-001-0836-x REVIEW Gerald L. Kooyman Evolutionary and ecological aspects of some Antarctic and sub-Antarctic penguin distributions Received: 24 May 2001 / Accepted: 27 September 2001 / Published online: 13 November 2001 © Springer-Verlag 2001 Abstract Penguins probably originated in the core of edge. Less is known about penguins during the pelagic Gondwanaland when South America, Africa, and Ant- phase between breeding cycles. What we do know is sur- arctica were just beginning to separate. As the continents prising in regard to their dispersal, which ranges from drifted apart, the division filled with what became the hundreds to thousands of kilometers from the breeding southern ocean. One of the remaining land masses colonies. moved south and was caught at the pole by the Earth’s rotation. It became incrusted with ice and is now known Keywords Aptenodytes · Eudyptes · Platform transmitter as East Antarctica. Linking it to South America was a terminal · Pygoscelis · Time-depth recorder series of submerged mountain ranges that formed a neck- lace of islands. The northern portion of the necklace, called the Scotia Arc, is now the “fertile crescent” of the Introduction Southern Ocean. The greatest numbers and biomass of penguins are found here as well as that of krill, the pri- Penguins are one of the oldest, most aquatic, and argu- mary prey species of most penguins, and many other ably most mystifying groups of birds. Their adaptation to marine predators. Today penguins are found throughout the sea was most likely a conversion from a procellariid the sub-Antarctic islands and around the entire Antarctic type of flying bird, such as a diving petrel (Simpson continent. -

MARINE ORNITHOLOGY 1999 Proceedings of the Third International Penguin Conference

Vol. 27MARINE ORNITHOLOGY 1999 Proceedings of the Third International Penguin Conference Contents PREFACE.................................................................................................................................................................................. ii J.P. CROXALL & L.S. DAVIS. Penguins: paradoxes and patterns.................................................................................... 1–12 A.F. CHIARADIA & K.R. KERRY. Daily nest attendance and breeding performance in the Little Penguin Eudyptula minor at Phillip Island, Australia ..............................................................................................................13–20 M. FORTESCUE. Temporal and spatial variation in breeding success of the Little Penguin Eudyptula minor on the east coast of Australia ..........................................................................................................21–28 R. McKAY, C. LALAS, D. McKAY & S. McCONKEY. Nest-site selection by Yellow-eyed Penguins Megadyptes antipodes on grazed farmland .................................................................................................29–35 C.C. ST CLAIR, I.G. McLEAN, J.O. MURIE, S.M. PHILLIPSON & B.J.S. STUDHOLME. Fidelity to nest site and mate in Fiordland Crested Penguins Eudyptes pachyrhynchus .............................................................37–41 J.-B. CHARRASSIN, C.-A. BOST, K. PÜTZ, J. LAGE, T. DAHIER & Y. LE MAHO. Changes in depth utilization in relation to the breeding stage: a case study with the King -

A B O U T P E N G U I N S Penguins Are Aquatic, Flightless Birds of the Family

A b o u t P e n g u i n s Penguins are aquatic, flightless birds of the family Spheniscidae. All are native to the southern hemisphere, where they inhabit every continent from the equator to Antarctica. Penguins primarily eat krill, squid, and fish. Adult penguins of all species have countershaded plumage—dark dorsal feathers and white ventral feathers—that help camouflage them in water. Penguins of the genus Eudyptes have yellow or orange feathered crests adorning their heads. Climate change threatens penguins in many ways, affecting breeding seasons and nesting habitats; prey populations, distributions, and accessibility; and predator populations and distributions. Human activity also threatens penguins, from overfishing, pollution, tourism, and construction to hunting and the introduction of non-native predators. The table below lists conservation status and native countries of occurrence for the 18 species of penguin monitored by the International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN) Red List. S p e c i e s S t a t u s N a t i v e C o u n t r i e s o f T r e n d O c c u r r e n c e Emperor Penguin Near Threatened Antarctica Aptenodytes forsteri Unknown King Penguin Least Concern Argentina; Chile; Falkland Islands (Malvinas); French Aptenodytes patagonicus Increasing Southern Territories; Heard Island and McDonald Islands; South Africa; South Georgia and the South Sandwich Islands Southern Rockhopper Penguin Vulnerable Argentina; Australia; Chile; Falkland Islands Eudyptes chrysocome Decreasing (Malvinas); French Southern Territories; -

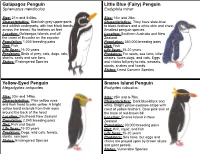

Penguin Cards

Galápagos Penguin Little Blue (Fairy) Penguin Spheniscus mendiculus Eudyptula minor Size: 21in and 5-6lbs. Size: 16in and 2lbs. Characteristics: Blackish-grey upper-parts Characteristics: They have slate-blue and whitish underparts, with two black bands to black feathers and a white chin and chest. across the breast. No feathers on feet Smallest penguin species Location: Galápagos Islands and off Location: Southern Australia and New the coast of Ecuador on the equator Zealand Population: 1,000 breeding pairs Population: 350,000 breeding pairs Diet: Fish Diet: Fish Life Span: 15-20 years Life Span: 15-20 years Predators: Birds of prey, cats, dogs, rats, Predators: Fur seals, sea lions, killer sharks, seals and sea lions. whales, foxes,dogs, and cats. Eggs Status: Endangered Species and chicks fall prey to rats, weasels, stoats, snakes and lizards. Status: Least Concern Species Yellow-Eyed Penguin Snares Island Penguin Megadyptes antipodes Eudyptes robustus Size: 30in and 14lbs. Size: 25in and 6-7lbs. Characteristics: Pale yellow eyes Characteristics: Dark blue-black and and their head is pale yellow. A bright white. Bright yellow eyebrow-stripe with yellow band extends from their eyes crest of yellow feathers. Bare pink skin at around the back of the head the base of red-brown bill Location: Southeast New Zealand Location: Snares Island in New Population: 2,240 breeding pairs Zealand Diet: Fish and Squid Population: 30,000 breeding pairs Life Span: 15-20 years Diet: Krill, squid, and fish Predators: Dogs, wild cats, ferrets, Life Span: 15-20 years stoats, sea lions Predators: Sea lions, but eggs and Status: Endangered Species chicks are preyed upon by brown skuas and giant petrels. -

Trophic Ecology of Breeding Northern Rockhopper Penguins, Eudyptes Moseleyi, at Tristan Da Cunha, South Atlantic Ocean

TROPHIC ECOLOGY OF BREEDING NORTHERN ROCKHOPPER PENGUINS, EUDYPTES MOSELEYI, AT TRISTAN DA CUNHA, SOUTH ATLANTIC OCEAN A Thesis submitted in the fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Masters in Marine Biology at Rhodes University By JENNY MARIE BOOTH December 2011 Abstract Northern Rockhopper penguin populations, Eudyptes moseleyi, are declining globally, and at Tristan da Cunha have undergone severe declines (> 90% in the last 130 years), the cause(s) of which are unknown. There is a paucity of data on this species in the South Atlantic Ocean, therefore their trophic ecology at Tristan da Cunha was studied, specifically focusing on diet, using stomach content analysis and stable isotope analysis (SIA), in conjunction with an analysis of diving behaviour, assessed using temperature-depth recorders. In order to evaluate the influence of gender on foraging, a morphometric investigation of sexual dimorphism was confirmed using molecular analysis. Additionally, plasma corticosterone levels were measured to examine breeding stage and presence of blood parasites as potential sources of stress during the breeding season. Northern Rockhopper penguins at Tristan da Cunha displayed a high degree of foraging plasticity, and fed opportunistically on a wide variety of prey, probably reflecting local small-scale changes in prey distribution. Zooplankton dominated (by mass) the diet of guard stage females, whereas small meso-pelagic fish (predominantly Photichthyidae) dominated diet of adults of both sexes in the crèche stage, with cephalopods contributing equally in both stages. Adults consistently fed chicks on lower-trophic level prey (assessed using SIA), probably zooplankton, than they consumed themselves indicating that the increasing demands of growing chicks were not met by adults through provisioning of higher-quality prey. -

Diving Patterns in Relation to Diet of Gentoo and Macaroni Penguins At

The Condor 90:157-167 0 TheCooper Ornithological Society 1988 DIVING PATTERNS IN RELATION TO DIET OF GENT00 AND MACARONI PENGUINS AT SOUTH GEORGIA ’ J. P. CROXALL British Antarctic Survey,Natural EnvironmentalResearch Council, High Cross,Madingley Road, CambridgeCB3 OET, UK R. W. DAVIS Sea World ResearchInstitute, Hubbs Marine ResearchCenter, 1700 South ShoresRoad, San Diego, CA 92109 M. J. O’CONNELL British Antarctic Survey,Natural EnvironmentalResearch Council, High Cross,Madingley Road, CambridgeCB3 OET, UK Abstract. The depthsattained on 1,444dives by 14 GentooPenguins (Pygoscelis Papua) and 6,352dives by eightMacaroni Penguins (Eudyptes chrysolophus) were recorded,together with the timing and durationof the foragingtrip and the amountand type of prey caught. MacaroniPenguins ate only Antarctickrill Euphausiasuperba. When feedingonly at night they madeno divesdeeper than 20 m; on all-day trips 36% of diveswere between 20 to 80 m. GentooPenguins fed during the day.When theycaught krill, 77%of diveswere shallower than 54 m; when fish were taken, 59% of dives were 54 to 136 m, which is consistent with the benthic-demersalhabit of thejuvenile Nototheniaand Champsocephalusfish they eat. The patternof predationon krill by both penguinspecies is consistentwith its vertical migrationto the surfaceat night and dispersalthrough the water column during the day. The food requirements of chick-rearing Macaroni Penguinswould be met by catching at least six adult krill per dive (or 150 juvenile krill or amphipods). For similar Gentoo Penguins,a minimum of 15 adult krill per dive (one every 8 set), or one fish every third dive, is needed. Recorded interannual variations in krill size can treble these rates, which would also be doubled if half the dives were for travelling, not feeding. -

Penguin (Eudyptes Chrysocome Moseleyi)

Polar Biol 02000) 23: 812±816 Ó Springer-Verlag 2000 ORIGINAL PAPER Charles M. Drabek á Yann Tremblay Morphological aspects of the heart of the northern rockhopper penguin Eudyptes chrysocome moseleyi ): possible implication in diving behavior and ecology? Accepted: 20 May 2000 Abstract We compared the heart morphology of the Kooyman and Ponganis 1997; Schreer and Kovacs 1997; small, deep-diving northern rockhopper penguin to the Kooyman and Ponganis 1998). Drabek 01989) published hearts of small, shallow-diving and large, deep-diving the ®rst suggestion that the heart morphology of pen- penguin species. The rockhopper penguin had a heart guins might play a role in their diving capabilities. He larger than expected for its body mass, and its heart noted that the penguin heart size relative to body mass weight/body weight was signi®cantly greater than in the 0heart ratio) was larger than expected for birds and that larger Ade lie penguin. We found the rockhopper's right the right ventricle of the emperor penguin 0Aptenodytes ventricle weight/heart weight to be signi®cantly greater forsteri) was more muscular in proportion to both the than this relationship in both the larger chinstrap and left ventricle and the heart than that of the chinstrap Ade lie penguins. The relationship of the right to left 0Pygoscelis antarctica) and Ade lie penguins 0P. adeliae). ventricular weights in the rockhopper heart is not dif- The long, deep diving capabilities of the emperor pen- ferent to that of the large, deepest-diving emperor pen- guin have long been documented 0Kooyman et al. 1971), guin.