Effects of a Devaluation on Trade Balance in Uganda: an ARDL Cointegration Approach

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Dollarization in Tanzania

Working paper Dollarization in Tanzania Empirical Evidence and Cross-Country Experience Panteleo Kessy April 2011 Dollarization in Tanzania: Empirical Evidence and Cross-Country Experience Abstract The use of U.S dollar as unit of account, medium of exchange and store of value in Tanzania has raised concerns among policy makers and the general public. This paper attempts to shed some light on the key stylized facts of dollarization in Tanzania and the EAC region. We show that compared to other EAC countries, financial dollarization in Tanzania is high, but steadily declining. We also present some evidence of creeping transaction dollarization particularly in the education sector, apartment rentals in some parts of major cities and a few imported consumer goods such as laptops and pay TV services. An empirical analysis of the determinants of financial dollarization is provided for the period 2001 to 2009. Based on the findings and drawing from the experience of other countries around the world, we propose some policy measures to deal with prevalence of dollarization in the country. Acknowledgment: I am thankful to the IGC and the Bank of Tanzania for facilitating work on this paper. I am particularly grateful to Christopher Adam and Steve O’Connell for valuable discussions and comments on the first draft of this paper. However, the views expressed in this paper are solely my own and do not necessarily reflect the official views of any institution with which I’m affiliated. 2 Dollarization in Tanzania: Empirical Evidence and Cross-Country Experience 1. Introduction One of the most notable effects of the recent financial sector liberalization in Tanzania is the increased use of foreign currency (notably the U.S dollar) as a way of holding wealth and a means of transaction for goods and services by the domestic residents. -

Currency Codes COP Colombian Peso KWD Kuwaiti Dinar RON Romanian Leu

Global Wire is an available payment method for the currencies listed below. This list is subject to change at any time. Currency Codes COP Colombian Peso KWD Kuwaiti Dinar RON Romanian Leu ALL Albanian Lek KMF Comoros Franc KGS Kyrgyzstan Som RUB Russian Ruble DZD Algerian Dinar CDF Congolese Franc LAK Laos Kip RWF Rwandan Franc AMD Armenian Dram CRC Costa Rican Colon LSL Lesotho Malati WST Samoan Tala AOA Angola Kwanza HRK Croatian Kuna LBP Lebanese Pound STD Sao Tomean Dobra AUD Australian Dollar CZK Czech Koruna LT L Lithuanian Litas SAR Saudi Riyal AWG Arubian Florin DKK Danish Krone MKD Macedonia Denar RSD Serbian Dinar AZN Azerbaijan Manat DJF Djibouti Franc MOP Macau Pataca SCR Seychelles Rupee BSD Bahamian Dollar DOP Dominican Peso MGA Madagascar Ariary SLL Sierra Leonean Leone BHD Bahraini Dinar XCD Eastern Caribbean Dollar MWK Malawi Kwacha SGD Singapore Dollar BDT Bangladesh Taka EGP Egyptian Pound MVR Maldives Rufi yaa SBD Solomon Islands Dollar BBD Barbados Dollar EUR EMU Euro MRO Mauritanian Olguiya ZAR South African Rand BYR Belarus Ruble ERN Eritrea Nakfa MUR Mauritius Rupee SRD Suriname Dollar BZD Belize Dollar ETB Ethiopia Birr MXN Mexican Peso SEK Swedish Krona BMD Bermudian Dollar FJD Fiji Dollar MDL Maldavian Lieu SZL Swaziland Lilangeni BTN Bhutan Ngultram GMD Gambian Dalasi MNT Mongolian Tugrik CHF Swiss Franc BOB Bolivian Boliviano GEL Georgian Lari MAD Moroccan Dirham LKR Sri Lankan Rupee BAM Bosnia & Herzagovina GHS Ghanian Cedi MZN Mozambique Metical TWD Taiwan New Dollar BWP Botswana Pula GTQ Guatemalan Quetzal -

Crown Agents Bank's Currency Capabilities

Crown Agents Bank’s Currency Capabilities August 2020 Country Currency Code Foreign Exchange RTGS ACH Mobile Payments E/M/F Majors Australia Australian Dollar AUD ✓ ✓ - - M Canada Canadian Dollar CAD ✓ ✓ - - M Denmark Danish Krone DKK ✓ ✓ - - M Europe European Euro EUR ✓ ✓ - - M Japan Japanese Yen JPY ✓ ✓ - - M New Zealand New Zealand Dollar NZD ✓ ✓ - - M Norway Norwegian Krone NOK ✓ ✓ - - M Singapore Singapore Dollar SGD ✓ ✓ - - E Sweden Swedish Krona SEK ✓ ✓ - - M Switzerland Swiss Franc CHF ✓ ✓ - - M United Kingdom British Pound GBP ✓ ✓ - - M United States United States Dollar USD ✓ ✓ - - M Africa Angola Angolan Kwanza AOA ✓* - - - F Benin West African Franc XOF ✓ ✓ ✓ - F Botswana Botswana Pula BWP ✓ ✓ ✓ - F Burkina Faso West African Franc XOF ✓ ✓ ✓ - F Cameroon Central African Franc XAF ✓ ✓ ✓ - F C.A.R. Central African Franc XAF ✓ ✓ ✓ - F Chad Central African Franc XAF ✓ ✓ ✓ - F Cote D’Ivoire West African Franc XOF ✓ ✓ ✓ ✓ F DR Congo Congolese Franc CDF ✓ - - ✓ F Congo (Republic) Central African Franc XAF ✓ ✓ ✓ - F Egypt Egyptian Pound EGP ✓ ✓ - - F Equatorial Guinea Central African Franc XAF ✓ ✓ ✓ - F Eswatini Swazi Lilangeni SZL ✓ ✓ - - F Ethiopia Ethiopian Birr ETB ✓ ✓ N/A - F 1 Country Currency Code Foreign Exchange RTGS ACH Mobile Payments E/M/F Africa Gabon Central African Franc XAF ✓ ✓ ✓ - F Gambia Gambian Dalasi GMD ✓ - - - F Ghana Ghanaian Cedi GHS ✓ ✓ - ✓ F Guinea Guinean Franc GNF ✓ - ✓ - F Guinea-Bissau West African Franc XOF ✓ ✓ - - F Kenya Kenyan Shilling KES ✓ ✓ ✓ ✓ F Lesotho Lesotho Loti LSL ✓ ✓ - - E Liberia Liberian -

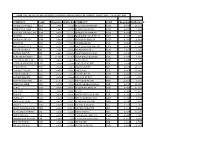

ZIMRA Rates of Exchange for Customs Purposes for Period 24 Dec 2020 To

ZIMRA RATES OF EXCHANGE FOR CUSTOMS PURPOSES FOR THE PERIOD 24 DEC 2020 - 13 JAN 2021 ZWL CURRENCY CODE CROSS RATEZIMRA RATECURRENCY CODE CROSS RATEZIMRA RATE ANGOLA KWANZA AOA 7.9981 0.1250 MALAYSIAN RINGGIT MYR 0.0497 20.1410 ARGENTINE PESO ARS 1.0092 0.9909 MAURITIAN RUPEE MUR 0.4819 2.0753 AUSTRALIAN DOLLAR AUD 0.0162 61.7367 MOROCCAN DIRHAM MAD 0.8994 1.1119 AUSTRIA EUR 0.0100 99.6612 MOZAMBICAN METICAL MZN 0.9115 1.0972 BAHRAINI DINAR BHD 0.0046 217.5176 NAMIBIAN DOLLAR NAD 0.1792 5.5819 BELGIUM EUR 0.0100 99.6612 NETHERLANDS EUR 0.0100 99.6612 BOTSWANA PULA BWP 0.1322 7.5356 NEW ZEALAND DOLLAR NZD 0.0173 57.6680 BRAZILIAN REAL BRL 0.0631 15.8604 NIGERIAN NAIRA NGN 4.7885 0.2088 BRITISH POUND GBP 0.0091 109.5983 NORTH KOREAN WON KPW 11.0048 0.0909 BURUNDIAN FRANC BIF 23.8027 0.0420 NORWEGIAN KRONER NOK 0.1068 9.3633 CANADIAN DOLLAR CAD 0.0158 63.4921 OMANI RIAL OMR 0.0047 212.7090 CHINESE RENMINBI YUANCNY 0.0800 12.5000 PAKISTANI RUPEE PKR 1.9648 0.5090 CUBAN PESO CUP 0.3240 3.0863 POLISH ZLOTY PLN 0.0452 22.1111 CYPRIOT POUND EUR 0.0100 99.6612 PORTUGAL EUR 0.0100 99.6612 CZECH KORUNA CZK 0.2641 3.7860 QATARI RIYAL QAR 0.0445 22.4688 DANISH KRONER DKK 0.0746 13.4048 RUSSIAN RUBLE RUB 0.9287 1.0768 EGYPTIAN POUND EGP 0.1916 5.2192 RWANDAN FRANC RWF 12.0004 0.0833 ETHOPIAN BIRR ETB 0.4792 2.0868 SAUDI ARABIAN RIYAL SAR 0.0459 21.8098 EURO EUR 0.0100 99.6612 SINGAPORE DOLLAR SGD 0.0163 61.2728 FINLAND EUR 0.0100 99.6612 SPAIN EUR 0.0100 99.6612 FRANCE EUR 0.0100 99.6612 SOUTH AFRICAN RAND ZAR 0.1792 5.5819 GERMANY EUR 0.0100 99.6612 -

![Demonyms: Names of Nationalities [Demonym Is a Name Given to a People Or Inhabitants of a Place.] Country Demonym* Country Demonym*](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/7054/demonyms-names-of-nationalities-demonym-is-a-name-given-to-a-people-or-inhabitants-of-a-place-country-demonym-country-demonym-887054.webp)

Demonyms: Names of Nationalities [Demonym Is a Name Given to a People Or Inhabitants of a Place.] Country Demonym* Country Demonym*

17. Useful Tables Th is chapter contains useful tables presented in GPO style. Th e tables display various design features most frequently used in Government publications and can be considered examples of GPO style. U.S. Presidents and Vice Presidents President Years Vice President Years George Washington ....................................... (1789–1797) John Adams .................................................... (1789–1797) John Adams ..................................................... (1797–1801) Th omas Jeff erson ........................................... (1797–1801) Th omas Jeff erson ............................................ (1801–1809) Aaron Burr...................................................... (1801–1805) George Clinton .............................................. (1805–1809) James Madison ................................................ (1809–1817) George Clinton .............................................. (1809–1812) Vacant .............................................................. (1812–1813) Elbridge Gerry ............................................... (1813–1814) Vacant .............................................................. (1814–1817) James Monroe.................................................. (1817–1825) Daniel D. Tompkins ..................................... (1817–1825) John Quincy Adams ...................................... (1825–1829) John C. Calhoun ............................................ (1825–1829) Andrew Jackson .............................................. (1829–1837) -

AGI Markets Monitor: Rising Commodity Prices, Mozambique's

AGI Markets Monitor: Rising commodity prices, Mozambique’s debt crisis, and Nigeria’s parallel exchange market October 2016 update The Africa Growth Initiative (AGI) Markets Monitor aims to provide up-to-date financial market and foreign exchange analysis for Africa watchers with a wide range of economic, business, and financial interests in the continent. Following the May 2016 and July 2016 updates, the October 2016 update continues tracking the diverse performances of African financial and foreign exchange markets through September 30, 2016. We offer our main findings on key recent events influencing the region’s economies: the recent rise of fuel and metal prices, Mozambique’s and Nigeria’s credit rating downgrades, and the fall of the Nigerian naira following the June 2016 implementation of the flexible exchange rate system. Commodity prices continue upward trend From January to September 2016, the International Monetary Fund’s (IMF) all commodity price index increased by 23 percent, especially bolstered by mounting fuel and metals prices, as shown in Figures 1 and 2. According to the IMF’s October 2016 World Economic Outlook, the increases in fuel prices have been driven in large part by rising natural gas prices in the U.S. (due to weather trends), surging coal prices in Australia and South Africa, and gradually increasing crude oil prices, which, after hitting a 10-year low in January 2016, have risen by 50 percent to $45 in August. On September 28, the Organization of the Petroleum Exporting Countries (OPEC) agreed to reduce crude output to between 32.5 to 33 million barrels a day, increasing spot oil prices by $2.5/bbl. -

Countries Codes and Currencies 2020.Xlsx

World Bank Country Code Country Name WHO Region Currency Name Currency Code Income Group (2018) AFG Afghanistan EMR Low Afghanistan Afghani AFN ALB Albania EUR Upper‐middle Albanian Lek ALL DZA Algeria AFR Upper‐middle Algerian Dinar DZD AND Andorra EUR High Euro EUR AGO Angola AFR Lower‐middle Angolan Kwanza AON ATG Antigua and Barbuda AMR High Eastern Caribbean Dollar XCD ARG Argentina AMR Upper‐middle Argentine Peso ARS ARM Armenia EUR Upper‐middle Dram AMD AUS Australia WPR High Australian Dollar AUD AUT Austria EUR High Euro EUR AZE Azerbaijan EUR Upper‐middle Manat AZN BHS Bahamas AMR High Bahamian Dollar BSD BHR Bahrain EMR High Baharaini Dinar BHD BGD Bangladesh SEAR Lower‐middle Taka BDT BRB Barbados AMR High Barbados Dollar BBD BLR Belarus EUR Upper‐middle Belarusian Ruble BYN BEL Belgium EUR High Euro EUR BLZ Belize AMR Upper‐middle Belize Dollar BZD BEN Benin AFR Low CFA Franc XOF BTN Bhutan SEAR Lower‐middle Ngultrum BTN BOL Bolivia Plurinational States of AMR Lower‐middle Boliviano BOB BIH Bosnia and Herzegovina EUR Upper‐middle Convertible Mark BAM BWA Botswana AFR Upper‐middle Botswana Pula BWP BRA Brazil AMR Upper‐middle Brazilian Real BRL BRN Brunei Darussalam WPR High Brunei Dollar BND BGR Bulgaria EUR Upper‐middle Bulgarian Lev BGL BFA Burkina Faso AFR Low CFA Franc XOF BDI Burundi AFR Low Burundi Franc BIF CPV Cabo Verde Republic of AFR Lower‐middle Cape Verde Escudo CVE KHM Cambodia WPR Lower‐middle Riel KHR CMR Cameroon AFR Lower‐middle CFA Franc XAF CAN Canada AMR High Canadian Dollar CAD CAF Central African Republic -

Prospects for a Monetary Union in the East Africa Community: Some Empirical Evidence

Department of Economics and Finance Working Paper No. 18-04 , Guglielmo Maria Caporale, Hector Carcel Luis Gil-Alana Prospects for A Monetary Union in the East Africa Community: Some Empirical Evidence May 2018 Economics and Finance Working Paper Series Paper Working Finance and Economics http://www.brunel.ac.uk/economics PROSPECTS FOR A MONETARY UNION IN THE EAST AFRICA COMMUNITY: SOME EMPIRICAL EVIDENCE Guglielmo Maria Caporale Brunel University London Hector Carcel Bank of Lithuania Luis Gil-Alana University of Navarra May 2018 Abstract This paper examines G-PPP and business cycle synchronization in the East Africa Community with the aim of assessing the prospects for a monetary union. The univariate fractional integration analysis shows that the individual series exhibit unit roots and are highly persistent. The fractional bivariate cointegration tests (see Marinucci and Robinson, 2001) suggest that there exist bivariate fractional cointegrating relationships between the exchange rate of the Tanzanian shilling and those of the other EAC countries, and also between the exchange rates of the Rwandan franc, the Burundian franc and the Ugandan shilling. The FCVAR results (see Johansen and Nielsen, 2012) imply the existence of a single cointegrating relationship between the exchange rates of the EAC countries. On the whole, there is evidence in favour of G-PPP. In addition, there appears to be a high degree of business cycle synchronization between these economies. On both grounds, one can argue that a monetary union should be feasible. JEL Classification: C22, C32, F33 Keywords: East Africa Community, monetary union, optimal currency areas, fractional integration and cointegration, business cycle synchronization, Hodrick-Prescott filter Corresponding author: Professor Guglielmo Maria Caporale, Department of Economics and Finance, Brunel University London, Uxbridge, Middlesex UB8 3PH, UK. -

Depreciation of the Ugandan Shilling: Implications for the National Economy

DEPRECIATION59th Session OF of theTHE State of UGANDANthe Nation Platform SHILLING: IMPLICATIONS FOR THE NATIONAL ECONOMY 59TH SESSION OF THE STATE OF THE NATION PLATFORM REPORT OF PROCEEDINGS 7TH AUGUST, 2015 AT PROTEA HOTEL KAMPALA Barbara Ntambirweki and Emma Jones STON Infosheet 59-Series 36, 2016 Abstract Over the course of 2014/15 fiscal year, State of the Nation (STON) Platform the Ugandan shilling depreciated to bring together key stakeholders against the US dollar by over 20%. for discussions on the likely impact Uganda, like many other economies, of the falling value of the Ugandan was struggling with the falling value shilling. Titled the “Depreciation of of its’ currency against the dollar the Ugandan Shilling: Implications for which was attributed to the fall in the National Economy”, three main export commodity prices, heavily recommendations emerged; chief impacted by export markets. This among them was the need to prioritise depreciation made mobilizing capital investment in the agricultural sector. from international markets difficult. Second was the need to pursue import Given the circumstances and the substitution and export promotion, and depreciation of the Ugandan shilling, thirdly the Government of Uganda long-term ramifications for the (GoU) was advised to prioritise the economy were likely. It was against adoption of an updated national this background that the Advocates monetary policy that reflected current Coalition for Development and economic needs. Environment (ACODE) held the 59th 1 DEPRECIATION OF THE UGANDAN SHILLING: IMPLICATIONS FOR THE NATIONAL ECONOMY Introduction Background The 59th STON Platform focused The 59th STON Platform was called at on understanding the implications a time when the value of the Ugandan of the depreciating value of the shilling had reached a record low of Ugandan shilling for the economy. -

PERFORMANCE of ECONOMY REPORT December 2017

PERFORMANCE OF ECONOMY REPORT December 2017 MACROECONOMIC POLICY DEPARTMENT MINISTRY OF FINANCE PLANNING AND ECONOMIC DEVELOPMENT www.finance.go.ug TABLE OF CONTENTS LIST OF ACRONYMS ......................................................................................................... 3 HIGHLIGHTS ........................................................................................................................ 4 1.0 REAL SECTOR DEVELOPMENTS ......................................................................... 5 1.1 Inflation Rate ................................................................................................................................. 5 1.2 Inflation Rates among EAC Partner States. ........................................................................ 6 1.3 Business Tendency Index (BTI) and Composite Index of Economic Activity(CIEA) 7 2.0 FINANCIAL SECTOR DEVELOPMENTS ............................................................. 9 2.1 Exchange Rate .............................................................................................................................. 9 2.2 Exchange Rates among EAC Partner States. ................................................................... 10 2.3 Private Sector Credit ................................................................................................................. 11 2.4 Government Securities ............................................................................................................ 13 2.5 Yields on Treasury Bills .......................................................................................................... -

WM/Refinitiv Closing Spot Rates

The WM/Refinitiv Closing Spot Rates The WM/Refinitiv Closing Exchange Rates are available on Eikon via monitor pages or RICs. To access the index page, type WMRSPOT01 and <Return> For access to the RICs, please use the following generic codes :- USDxxxFIXz=WM Use M for mid rate or omit for bid / ask rates Use USD, EUR, GBP or CHF xxx can be any of the following currencies :- Albania Lek ALL Austrian Schilling ATS Belarus Ruble BYN Belgian Franc BEF Bosnia Herzegovina Mark BAM Bulgarian Lev BGN Croatian Kuna HRK Cyprus Pound CYP Czech Koruna CZK Danish Krone DKK Estonian Kroon EEK Ecu XEU Euro EUR Finnish Markka FIM French Franc FRF Deutsche Mark DEM Greek Drachma GRD Hungarian Forint HUF Iceland Krona ISK Irish Punt IEP Italian Lira ITL Latvian Lat LVL Lithuanian Litas LTL Luxembourg Franc LUF Macedonia Denar MKD Maltese Lira MTL Moldova Leu MDL Dutch Guilder NLG Norwegian Krone NOK Polish Zloty PLN Portugese Escudo PTE Romanian Leu RON Russian Rouble RUB Slovakian Koruna SKK Slovenian Tolar SIT Spanish Peseta ESP Sterling GBP Swedish Krona SEK Swiss Franc CHF New Turkish Lira TRY Ukraine Hryvnia UAH Serbian Dinar RSD Special Drawing Rights XDR Algerian Dinar DZD Angola Kwanza AOA Bahrain Dinar BHD Botswana Pula BWP Burundi Franc BIF Central African Franc XAF Comoros Franc KMF Congo Democratic Rep. Franc CDF Cote D’Ivorie Franc XOF Egyptian Pound EGP Ethiopia Birr ETB Gambian Dalasi GMD Ghana Cedi GHS Guinea Franc GNF Israeli Shekel ILS Jordanian Dinar JOD Kenyan Schilling KES Kuwaiti Dinar KWD Lebanese Pound LBP Lesotho Loti LSL Malagasy -

Performance of the Economy Report October 2018

PERFORMANCE OF THE ECONOMY REPORT OCTOBER 2018 MACROECONOMIC POLICY DEPARTMENT MINISTRY OF FINANCE, PLANNING AND ECONOMIC DEVELOPMENT www.finance.go.ug TABLE OF CONTENTS LIST OF TABLES .............................................................................................................................. ii LIST OF FIGURES .......................................................................................................................... iii LIST OF ACRONYMS ..................................................................................................................... iv SUMMARY ........................................................................................................................................... v REAL SECTOR DEVELOPMENTS .............................................................................................. 1 Inflation ................................................................................................... 1 Indicators of Economic Activity................................................................. 2 Composite Index of Economic Activity (CIEA) .................................................................. 2 Business Tendency Index (BTI) ............................................................................................ 3 Purchasing Managers Index (PMI) ....................................................................................... 4 FINANCIAL SECTOR DEVELOPMENTS .................................................................................. 5 Exchange