Dating Earthworks Using Optically-Stimulated Luminescence

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Cubert Parish News Nowodhow an Bluw

Cubert Parish News Nowodhow an Bluw Photo NOVEMBER 2020 courtesy of Karen Green PHOTO COURTESY OF JULIA BECKFORD – From Jubilee Close towards Penhale – October 13th SEE PAGE 3 REGARDING POPPY PURCHASES PLEASE NOTE THAT ADVERTS AND ARTICLES FOR THE JANUARY 2021 NEWSLETTER NEED TO BE IN BY MONDAY 14TH DECEMBER – THANKS Printed by Unit 6C, Treloggan Industrial Estate, Newquay TR7 2SX 01637 874012 NOVEMBER 2020 ADVERTISEMENTS 2 NOVEMBER 2020 POPPY APPEAL 3 NEWSLETTER CONTACTS & INFORMATION NOVEMBER 2020 ADVERTISEMENT 4 NOVEMBER 2020 XMAS LIGHTS / POEMS 5 Gazing out From Hoblyn’s Cove Seagulls wheel And Jackdaws rove Down below A turquoise blue Foaming waves With greenish hue Horizon red A melting sun Rippled sea Gold shadows spun PHIL One Morning; Two Spiders Little spider, have you been busy all night? Spinning your perfect web until just right- Between body and wing mirror on my car Hoping that today I’m not travelling far. Big spider, you have such fantastic cheek! For instead of waiting, silent and meek You are trying to take over my rotary line, You must go, no home here, this ‘web’ is mine. JOY NOVEMBER 2020 ADVERTISEMENT 6 NOVEMBER 2020 ANSWERS 7 NOVEMBER 2020 ADVERTISEMENT 8 NOVEMBER 2020 TALKING NEWSPAPER 9 NOVEMBER 2020 PTFA FUNDRAISING 10 NOVEMBER 2020 PTFA FUNDRAISING 11 Email : [email protected] Web Site : www.spanglefish.com/cubertnews NOVEMBER 2020 CREATIVES / LOCAL HELP 12 NOVEMBER 2020 MESSAGES / ECO NEWS 13 New Series on the TV Starts Tuesday 3rd November at 9pm on Really Channel – Freeview 17, Sky 142, Virgin 128, -

Cornwall Council Altarnun Parish Council

CORNWALL COUNCIL THURSDAY, 4 MAY 2017 The following is a statement as to the persons nominated for election as Councillor for the ALTARNUN PARISH COUNCIL STATEMENT AS TO PERSONS NOMINATED The following persons have been nominated: Decision of the Surname Other Names Home Address Description (if any) Returning Officer Baker-Pannell Lisa Olwen Sun Briar Treween Altarnun Launceston PL15 7RD Bloomfield Chris Ipc Altarnun Launceston Cornwall PL15 7SA Branch Debra Ann 3 Penpont View Fivelanes Launceston Cornwall PL15 7RY Dowler Craig Nicholas Rivendale Altarnun Launceston PL15 7SA Hoskin Tom The Bungalow Trewint Marsh Launceston Cornwall PL15 7TF Jasper Ronald Neil Kernyk Park Car Mechanic Tredaule Altarnun Launceston Cornwall PL15 7RW KATE KENNALLY Dated: Wednesday, 05 April, 2017 RETURNING OFFICER Printed and Published by the RETURNING OFFICER, CORNWALL COUNCIL, COUNCIL OFFICES, 39 PENWINNICK ROAD, ST AUSTELL, PL25 5DR CORNWALL COUNCIL THURSDAY, 4 MAY 2017 The following is a statement as to the persons nominated for election as Councillor for the ALTARNUN PARISH COUNCIL STATEMENT AS TO PERSONS NOMINATED The following persons have been nominated: Decision of the Surname Other Names Home Address Description (if any) Returning Officer Kendall Jason John Harrowbridge Hill Farm Commonmoor Liskeard PL14 6SD May Rosalyn 39 Penpont View Labour Party Five Lanes Altarnun Launceston Cornwall PL15 7RY McCallum Marion St Nonna's View St Nonna's Close Altarnun PL15 7RT Richards Catherine Mary Penpont House Altarnun Launceston Cornwall PL15 7SJ Smith Wes Laskeys Caravan Farmer Trewint Launceston Cornwall PL15 7TG The persons opposite whose names no entry is made in the last column have been and stand validly nominated. -

Launceston-And-Districts-Fallen-From-Both-World-Wars..Pdf

This is not a complete record of all those that fell during the two wars, with some of the fallen having no information available whatsoever. However there are 222 names from within the district that I have been able to provide a narrative for and this booklet hopefully will provide a lasting memory for future generations to view and understand the lives behind the names on the various memorials around Launceston. It has not been easy piecing together the fragments of information particularly from the first world war where many records were destroyed in the blitz of the second world war, but there are many resources now available that do make the research a little easier. Hopefully over time the information that is lack- ing in making this a complete story will be discovered and I can bring all the re- cords up to date. Of course there have been many people that have helped and I would like to thank Peter Bailey, Claudine Malaquin, Dennis Middleton, Jim Edwards, Martin Kel- land, Grant Lethbridge Morris and Michael Willis for their invaluable help in compiling this homage plus the resources that are freely available at Launceston Library. My hope is that the people will find this a fascinating story to all these souls that bravely gave their lives in the service of their country and that when we come to remember them at the various remembrance services, we will actually know who they were. Roger Pyke 28th of October 2014. Launceston’s Fallen from World War One William Henry ADAMS William was born in 1886 at 14 Hillpark Cottages, Launceston to Richard and Jane Adams. -

1268 F.Ar Corn"Tall

1268 F.AR CORN"TALL. FARMERs-continued. Peters Edward, Trethinna, Alternun,' Phillips Thomas, Vounder, St. Blazey,. Pender WiIliam Frederick, Bryher, St. Launceston Par Station RS.O Mary's, Islands of Scilly Petersl".Beacon,St.Agnes,ScorrierR.S.O Phillips WaIter, Lombard, Lanteglos, Pender William John, Bryher, St. Peters Hugh, Burgotha, St.. Stephen's- Fowey RS.O Mary's, Islands of SCIlly in-Brannell, Grampound Road Phillips W. J.Bokiddick,Lanivet, Bodmin. Pendray James, Nancemelling, Gwy- Peters John,Kennall mills, St.Stythians, PhillipsWm.Egloshyle.SladesBrdg.RS.O thian, HayIe Perran-Arworthal RS.O Phillips Wm. Hendra, Kenwyn, Trnro Pendray Peter, Kehelland, Camborne Peters John, ~ancemellan, Kehelland, Phillips WiIliam, Pool, Carn Brea RS.O Pendray William, Bodithiel, St. Pin- Camborne PhillipsW.Rosenea,Lanlivery,Lostwithiel nock, Liskeard Peters J. Tremorvab, Budock, Falmouth Phillips William, Trebiskin & Ellenglaze, Peneluna William, Calvadnar:k, Carn- Peters John, Windsor Stoke, Stoke Cubert, Grampound Road menellis, Helston Climsland, Callington RS.O Phillips William John, Lawhibbet, St. Pengelley Nicholas, Trevawden, Herods- Peters S. GiUy vale, Gwennap, Redruth Sampson's, Par Station R.S.O foot, Liskeard Peters Thomas, Lannarth, Redruth Phillips WiIliam John, Tregonning,. Pengelley William, Carythenack, Con- Peters William, Beacon, St. Agnes, Luxulyan, Lostwithiel stantine, Penryn Scorrier R.S.O Philp John, Yolland, Linkinhorne,. Pengelly Miss Grace, Boswarthen, Peters W. Illand, North hill, Lanceston Callington RS.O Madron, Penzance Peters William,Trewithen, St.Stythians, Philp John, jun. Lancare & Cardwain &; Pengelly James, Tresquite mill, Lan- Perran-Arworthal R.S.O Cartowl, Pelynt, Duloe RS.O sallos, Polperro RS.O Petherick Thomas, Pempethey, Lan- Philp John Pearce, Downhouse, Stoke Pengelly John Henry, Wallace &; Lower teglos, Camelford Climsland, Callington RS.O Lacrenton, St. -

Edited by IJ Bennallick & DA Pearman

BOTANICAL CORNWALL 2010 No. 14 Edited by I.J. Bennallick & D.A. Pearman BOTANICAL CORNWALL No. 14 Edited by I.J.Bennallick & D.A.Pearman ISSN 1364 - 4335 © I.J. Bennallick & D.A. Pearman 2010 No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without prior permission of the copyright holder. Published by - the Environmental Records Centre for Cornwall & the Isles of Scilly (ERCCIS) based at the- Cornwall Wildlife Trust Five Acres, Allet, Truro, Cornwall, TR4 9DJ Tel: (01872) 273939 Fax: (01872) 225476 Website: www.erccis.co.uk and www.cornwallwildlifetrust.org.uk Cover photo: Perennial Centaury Centaurium scilloides at Gwennap Head, 2010. © I J Bennallick 2 Contents Introduction - I. J. Bennallick & D. A. Pearman 4 A new dandelion - Taraxacum ronae - and its distribution in Cornwall - L. J. Margetts 5 Recording in Cornwall 2006 to 2009 – C. N. French 9 Fitch‟s Illustrations of the British Flora – C. N. French 15 Important Plant Areas – C. N. French 17 The decline of Illecebrum verticillatum – D. A. Pearman 22 Bryological Field Meetings 2006 – 2007 – N. de Sausmarez 29 Centaurium scilloides, Juncus subnodulosus and Phegopteris connectilis rediscovered in Cornwall after many years – I. J. Bennallick 36 Plant records for Cornwall up to September 2009 – I. J. Bennallick 43 Plant records and update from the Isles of Scilly 2006 – 2009 – R. E. Parslow 93 3 Introduction We can only apologise for the very long gestation of this number. There is so much going on in the Cornwall botanical world – a New Red Data Book, an imminent Fern Atlas, plans for a new Flora and a Rare Plant Register, plus masses of fieldwork, most notably for Natural England for rare plants on SSSIs, that somehow this publication has kept on being put back as other more urgent tasks vie for precedence. -

COM 575 Wicca, Treveal, Tremedda, Tregerthen36 Long Stone Croft

Application Decision Hearing held on 18 February 2015 by Heidi Cruickshank BSc MSc MIPROW Appointed by the Secretary of State for Environment, Food and Rural Affairs Decision date: 21 April 2015 Application Ref: COM 575 Tremedda, Tregerthen, Wicca and Treveal Cliff, Zennor, Cornwall Register Unit No: CL7041 Commons Registration Authority: Cornwall Council The application, dated 26 March 2013, is made under paragraph 4 of Schedule 2 of the Commons Act 2006. The application is made by Mr D Coles on behalf of Save Penwith Moors. The application is to register waste land of a manor in the Register of Common Land. Decision 1. The application is approved in part. The land outlined and cross-hatched in red on the plan attached to this decision shall be added to the Register of Common Land (“the RCL”). Preliminary Matters Guidance 2. The applicants, Save Penwith Moors (“SPM”), argued that the Department for Environment, Food and Rural Affairs (“defra”) guidance that should be referred to in this case was that which was extant at the date of their application. The application was received by Cornwall Council, the Commons Registration Authority (“the CRA”) on 10 April 2013. 3. Cornwall was one of the pilot areas and, therefore, the “Part 1 of the Commons Act 2006, Guidance to commons registration authorities and the Planning Inspectorate for the pioneer implementation” was relevant guidance. Revisions have been made, with the latest, published in December 2014 (“the guidance”). “Part 1 of the Commons Act 2006, Guidance to commons registration authorities and the Planning Inspectorate”, version 2.0 relates to the full implementation of Part 1 of the Commons Act 2006 (“the 2006 Act”) in a minority of registration authorities and the partial implementation in remaining registration authorities through The Commons Registration (England) Regulations 20142. -

Cubert Housing Needs Survey Full Report

Cubert Parish HOUSING NEED SURVEY Report Date: 10th May 2019 Version: 1.1 Document Final Report Status: Affordable Housing Team, Author: Cornwall Council [email protected] Tel: 01726 223686 Cubert Parish Housing Need Survey Report Contents 1. Introduction ............................................................................................................................... 3 2. Current Housing Need Information .................................................................................. 4 2.1. Registered need on Cornwall HomeChoice ............................................................ 4 3. Survey Methodology ............................................................................................................... 4 3.1. Location and geographic extent of survey ............................................................ 4 3.2. Survey methodology ...................................................................................................... 5 3.3. Survey structure .............................................................................................................. 5 3.4. Report Format ................................................................................................................... 5 4. Survey Data ............................................................................................................................... 6 4.1. Summary of survey response rate ........................................................................... 6 4.2. Analysis of sample -

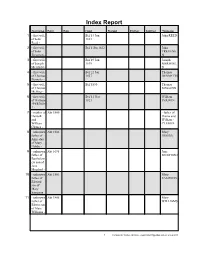

Index Report

Index Report Surname, Born Bap Died Buried Father Mother *Spouse 1 - first wife Bef 14 Jun John REED of John 1821 Reed - 2 - first wife Bef 1 Jan 1822 John of John TREVENE Trevenen - N 3 - first wife Bef 19 Jun Joseph of Joseph 1819 MERIFIEL Merifield - D 4 - first wife Bef 22 Jan Thomas of Thomas 1827 BENNETTS Bennetts - 5 - first wife Bef 1830 Thomas of Thomas MELLING Melling - 6 - first wife Bef 11 Nov William of William 1823 PERDON ?PERDON ? - 7 - mother of Abt 1800 - father of Hannah Hanna and and William - William CLEMES Clemes - 8 - unknown Abt 1806 Mary father of HOBBA Anne dau of Mary Hobba - 9 - unknown Abt 1695 Jane father of MUGFORD Bartholom ew son of Jane Mugford - 10 - unknown Abt 1801 Mary father of SAMPSON Edward son of Mary Sampson - 11 - unknown Abt 1806 Mary father of WILLIAMS Edwin son of Mary Williams - 1 Compiled by Wesley Johnston - [email protected] on 6 Aug 2011 Index Report Surname, Born Bap Died Buried Father Mother *Spouse 12 - unknown Abt 1814 Ursula father of ROWSE Edwin son of Ursula Rowse - 13 - unknown Abt 1806 Mary father of PRIOR Esther dau of Mary Prior - 14 - unknown Abt 1793 Jane father of HOBBA Jane Hobba daughter Anne - 15 - unknown Abt 1803 Jane father of HOBBA John son of Jane Hobba - 16 - unknown Abt 1795 Mary father of BONDS Joseph son of Mary Bonds - 17 - unknown Abt 1801 Elizabeth father of ROBERTS Patience dau of Elizabeth Roberts - 18 - unspecifi Abt 1794 Martha ed father BERRYMA of Eliza N dau of Martha Berryman - 19 - unspecifi Abt 1813 - unspecifie ed father d mother of of Mary Mary Anne Anne Prior - PRIOR - 20 - unspecifi Abt 1748 Mary ed father HAWKE of Mary dau of Mary Hawke - 2 Compiled by Wesley Johnston - [email protected] on 6 Aug 2011 Index Report Surname, Born Bap Died Buried Father Mother *Spouse 21 - wife of Abt 1870 Orville D. -

CORNWALL. FAR 1129 Phillips Samuel, Treveal, Cubert, Gram-' Pollard J

TRADES DIRECTORY.] CORNWALL. FAR 1129 Phillips Samuel, Treveal, Cubert, Gram-' Pollard J. H. Kemyell, St. Paul, Penzance' Pryor John, Skinner's Bottom, Mount pound Road Pollard Rd. Bod1re, Slades bridge R.S.O Hawke, Scorrier R.S.O Phillips Samuel, Tywarnbayle, Perran- Pollard Robert, Tregarrick, Menheniot, PryorJobn,Trelubtlus, ·wendron,Helston zabuloe, Truro Liskeard Pryor Jn. "Whealvor Godolpbin, Helston Phillips Thomas, Boswarren, Constan- Pollard Thos. Kuggar, Grade, Helston PryorMrs.Jobn,Treservern,St.Stythians, tine, Penryn Pollard Thomas, Trehunest, Quethiock, Perran-arworthal R.S.O Phillips Thomas, Marazion R.S.O Liskeard Pryor Joseph,Blackwater,Mount Hawke, Phillips Thomas, Mineral court, St. Polmear Samuel, Ludgvan, Penzance Scorrier R.S.O Stephens-in-Brannell, Grampound Rd Polmountain Isaac, Little Gilley, Godol- Pryor Thomas, Cam Brea R.S.O Pbillips W. Hendra, Kenwyn, Truro , pbin, Helston Pryor Ths. Crasken, Wendron, Helston Phillips William, Luxulyan, Lostwitbiel 1Polsue John, Harveys, Tywardreath, Par Pryor Ths. Fiscar,Carnmenellis,Redruth Phillips William, Marazion R.S.O station R.S 0 Pryor Thomas, Jericho row, Helston Phillips W. Rosenea, Lanlivery, Lost-\Pomery James, 'Vaterlow, St. Just-in- Pryor Thomas, Medlyn, Carnmenellis, w1tbiel Roseland, Grampound Road Redruth Phillips W. Roskrow, St. Gluvias,Penryn Pomery John, Tailor's cross, Kilkbamp- Pryor William, Ambrose house, Redruth Phillips William, Trebiskin, Cubert, ton, Stratton Highway, Treleigh, Redruth Grampound Road Pomery John, Trethem & Pulpry, St. Pryor William, Four Lanes, Redruth Phillips William, jun. Treveal, Cubert, Just-in-Roseland, Grampound Road Quentrall Rd. Crane, Wendron, Helston Gram pound Road Pomroy John, Trevigro, South hill, Quick Mrs. Elizth. Pembeagle, St. Ives Phillips W. J. Bokiddick,Lani>et,Bodmin Callington R.S.O Quick Miss Grace, Beagletubben, l'hillips William John, Cbywoon, ::lt. -

CORNWALL. but 1365 Male William Mably, Tredizzick, St

TRADES DIRECTORY.J CORNWALL. BUT 1365 Male William Mably, Tredizzick, St. Pearce John, Fore street, Hayle Sambell Cyrus, jun. Egloskerry R.S.O Minver, Wadcbridge R.S.O Pearce John, Market pl. St. Ives R.S.O Sampson Geo. 38 & 39 Market, Penzance Mallalue G.Holmbush,Par Station R.S.O Pearce John, 'fregenna pl. St.Ives R.S.O Sampson James, 37 Market, Penzance Manhire R.jun.Michell,GrampoundRoad Pearce R. J. Chacewater,Scorrier R.S.O Sampson Thomas, West end, HaylA Marshall Henry, King st. Bude R.S.O Pearce William, Calstock Saunders 'fhos. S 21 New st. Falmouth .Martin Jas. Higher Luccombe, La whit- Pearce Wm. Market, St. Ives R.S.O Scantlebury •r. l''ore st.Looe East R.S.O ton, Launceston Pellowe A. J. 16 Cross row ,Moor ,Falmth Scorse William, Croswolla, Helston 'Martin Joseph, Albaston, Tavistock Penberthy James,Fore st. St. Ives R.S.O Scott William Hy. 50 Forest. Saltash .Martin Richard, Uphill, Linkinhorne, Penlerick J. 14 Berkeley pi. Falmouth Searle William, Grampound Road Callington R.S.O Peuney Samuel, Maudlan, Liskeard Searle Wm. Newlyn, Grampound Road :Martin 'l'homas, jun. St. Dominick, St. Penprase James, 89 Forest. Redruth Sherris Jn. Hugh st.St.Mary's, Penzance MelliDll R.S.O Penrose William Henry, 3[ Alverton st. Slade Christopher, Duloe R.S.O :Mattthews (John) & Dawe (Joseph), & 56 Market, Penza.nce Smith Henry Daniel,Hewaswater,Creed, Metheri.l1, St. Mellion R.S.O PenroseW.H.Carharrack,ScorrierR.S.O Grampound Road May E. B. Polgooth, St. Ewe, St. Austell PenwardenDavid,ButleR.S.O.&Poughill, SmithJ.Penstraze moors,Kenwyn,'fruro .Matthews J. -

Autumn Newsletter No.39

The Butterfly Observer Cornwall Butterfly Conservation Newsletter No. 39 Brimstone Butterfly, Ponts Mill, April 1996. Photo © Lee Slaughter. Report, page 6. Butterfly Conservation Winter 2008 The Butterfly Observer - Winter 2008 Editorial y apologies for mis-spelling Betsy Vulliamy’s name in the last issue and also the Mmis-spelling of Tim and Sandy Dingle’s house as Peholt instead of Penhalt. Some ‘hawk-eyes’ among you may also have noticed ‘butterflies’ instead of ‘butterfly’s’ as well! The font in this issue has changed to 9 points to enable me to fit all the articles in. I hope it is readable to you all. There is much concern these days amongst some conservationists in Cornwall that their voice is not being heard adequately by the appropriate authorities. This sentiment is echoed by our retiring Transect Coordi- nator, Sally Foster in her article on page 7 and following - quite a comprehensive and personal report that I believe many will find cutting and to the point. Added at the end of the article is a detailed account of the transect areas in Cornwall. Those of you interested in golf may find the article on page 14 of interest. Roger Lane continues his observations on migrants in his article on page 5 and 6. Whilst Lee Slaughter informs us of the Narrow-bordered Bee Hawk-moth nectaring on Bugle. early Brimstone sightings also on page Marsland and Welcombe Nature Reserve, 24th April 6. 2007. Photo © Steve Ogden by kind permission. National Moth Day (and Night) this year will be held on Saturday 7th June. -

BIC-1974.Pdf

Officers 1975-76 President : Dr. C. J. F. Coombs, Greenwith Place, Perranwell, Truro Chairman : Mrs. M. P. Visick, Trendain, Perranwell Station, Truro General Secretary : W. J. A. Woodward, Lewidden, Penrose, St. Ervan, Wadebridge Treasurer & Registrar : A. F. Reynolds, 33, Treworder Road, Truro Assistant Treasurer 6v Registrar : P. J. Dwyer, 27, Trenance Road, Newquay Field Meetings : F. M. Couch, Old Polzeath, Wadebridge Conservation : G. Jackson, Treweege Barton, Stithians, Truro Editor : N. R. Phillips, Cucurrian Mill, Nancledra, Penzance Secretary for the Isles of Scilly : Miss II. M. Quick, Priglis, St. Agnes, Isles of Scilly Joint Editors—Isles of Scilly Journal : H. P. K. Robinson, D. B. Hunt, 14, Regent Terrace, The Blockhouse, Tresco, Penzance Isles of Scilly Officer for Youth & Education : Mrs. S. D. Johns, 25, Hillcrest Avenue, Truro Committee Members : S. D. Gunn (St. Columb), D. R. Carter (Fowey), R. J. Salmon (Bodmin), Mrs. K. West (Falmouth), retire 1976. B. N. Boothby (Newquay), J. E. Beckerlegge (Camborne), Mrs. E. Davies (St. Tudy), A. C. Hosking (Penzance), retire 1977. Mrs. A. II. Jeffreys (Wadebridge), Mrs. A. Robinson (Truro), Mrs. R. P. Weeks (Wadebridge), J. B. Bottomley (St. Ives), R. J. Beswetherick (Bude), J. Hawkey (Newquay), B. Wilson (Lostwithiel), retire 1978. and the Officers ex-officio. CORNWALL BIRD-WACHING AND PRESERVATION SOCIETY Fourty-Third ANNUAL REPORT 1974 St. George Printing Works Ltd., Camborne Secretary's Report for 1974 The Membership total shows a decline of approximately 100 (from 1100 to 1000) due to our Treasurer finding that the bulk of these Members were in arrears with subscriptions of from 2-3 years. Also quite a number were only paying 50p a year.