Optically Stimulated Luminescence Profiling and Dating of Earthworks

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Cubert Parish News Nowodhow an Bluw

Cubert Parish News Nowodhow an Bluw Photo NOVEMBER 2020 courtesy of Karen Green PHOTO COURTESY OF JULIA BECKFORD – From Jubilee Close towards Penhale – October 13th SEE PAGE 3 REGARDING POPPY PURCHASES PLEASE NOTE THAT ADVERTS AND ARTICLES FOR THE JANUARY 2021 NEWSLETTER NEED TO BE IN BY MONDAY 14TH DECEMBER – THANKS Printed by Unit 6C, Treloggan Industrial Estate, Newquay TR7 2SX 01637 874012 NOVEMBER 2020 ADVERTISEMENTS 2 NOVEMBER 2020 POPPY APPEAL 3 NEWSLETTER CONTACTS & INFORMATION NOVEMBER 2020 ADVERTISEMENT 4 NOVEMBER 2020 XMAS LIGHTS / POEMS 5 Gazing out From Hoblyn’s Cove Seagulls wheel And Jackdaws rove Down below A turquoise blue Foaming waves With greenish hue Horizon red A melting sun Rippled sea Gold shadows spun PHIL One Morning; Two Spiders Little spider, have you been busy all night? Spinning your perfect web until just right- Between body and wing mirror on my car Hoping that today I’m not travelling far. Big spider, you have such fantastic cheek! For instead of waiting, silent and meek You are trying to take over my rotary line, You must go, no home here, this ‘web’ is mine. JOY NOVEMBER 2020 ADVERTISEMENT 6 NOVEMBER 2020 ANSWERS 7 NOVEMBER 2020 ADVERTISEMENT 8 NOVEMBER 2020 TALKING NEWSPAPER 9 NOVEMBER 2020 PTFA FUNDRAISING 10 NOVEMBER 2020 PTFA FUNDRAISING 11 Email : [email protected] Web Site : www.spanglefish.com/cubertnews NOVEMBER 2020 CREATIVES / LOCAL HELP 12 NOVEMBER 2020 MESSAGES / ECO NEWS 13 New Series on the TV Starts Tuesday 3rd November at 9pm on Really Channel – Freeview 17, Sky 142, Virgin 128, -

BIC-1961.Pdf

TABLE OF CONTENTS PAGE Preamble ... ... ... ... ... ... 3 List of Contributors ... ... ... ... ... 5 Cornish Notes ... ... ... ... ... ... 7 Arrival and Departure of Cornish Migrants ... ... 44 Isles of Scilly Notes ... ... ... ... ... 49 Arrival and Departure of Migrants in the Isles of Sciily ... 59 Bird Notes from Round Island ... ... ... ... 62 Collared Doves at Bude ... ... ... ... ... 65 The Library ... ... ... ... ... ... 67 The Society's Rules ... ... ... ... ... 69 Balance Sheet ... ... ... ... ... ... 70 List of Members ... ... ... ... ... 71 Committees for 1961 and 1962 ... ... ... ... 84 Index ... ... ... ... ... ... ... 85 THIRTY-FIRST REPORT OF The Cornwall Bird-Watching and Preservation Society 1961 Edited by J. E. BECKERLEGGE, N. R. PHILLIPS and W. E. ALMOND Isles of Scilly Section edited by Miss H. M. QUICK The Society's Membership is now 660. During the year, fifty-one have joined the Society, but losses by death, resignation and removal from membership list because of non-payment of subscriptions were ninety. On February 11th a Meeting was held at the Museum, Truro, at which Mr. A. G. Parsons gave a talk on the identification of the Common British Warblers. This was followed by a discussion. The thirtieth Annual General Meeting was held in the Museum, Truro, on April 15th. The meeting stood in silence in memory of the late Col. Ryves, founder of the Society, and Mrs. Macmillan. At this meeting, Sir Edward Bolitho, Dr. R. H. Blair, Mr. S. A. Martyn and the Revd. J. E. Beckerlegge were re-elected as President, Chairman, Treasurer and Joint Secretary, respectively. In place of Dr. Allsop who had resigned from the Joint Secretaryship, Mr. N. R. Phillips was elected. The meeting also approved of a motion that Col. -

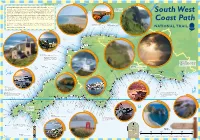

Distance in Miles from Poole Harbour. Distance in Miles from Minehead

W ate Wool rm aco o Valley mb u of e th Ro P C c The South West Coast Path is renowned as one of the world’s best walks. Its journey ho k to o s : P T v Minehead: h e e o around the edge of the Westcountry is like no other as it passes through five Areas of d to The start (or finish) of the F : o P S h h rm South West Coast Path Outstanding Natural Beauty, seventeen Heritage Coasts, a National Park, two World o i rl a t e n o y : T Heritage Sites, a UNESCO Geopark and Britain’s first UNESCO Biosphere reserve. B u r r n y e a r n The contrasting landscapes of wild, rugged beauty, bustling seaside resorts, idyllic C a t fishing villages, woodland, pastures and sandy beaches along the coast from h Minehead to the shores of Poole Harbour, are truly inspirational and every day walking the path brings stunning new experiences. Whether you are planning a 630 mile adventure along the entire path or an afternoon Culbone: Great Hangman (1043ft): stroll, the official South West Coast Path website has all the information you need. England's smallest parish church. The highest point on the Coast Path. www.southwestcoastpath.com 0.0 619.0 10.6 608.7 20.9 594.9 34.7 620.7 8.9 P en L 589.6 4 G ev h eir ol a Lynmouth Foreland LH. d nt all en M ic 629.6 0.0 C i ynmouth a n 582.9 46.7 e P L p P P o Culbone Church orlock W h h P o o i oint Combe Martin t to n Ilfracombe o: : N t M i Minehead ik g P e e h l Morte P K S o e o t m u o t : p h s a D Bra e l n y l a sc n 519m o m M b a 566.1 63.5 e r P t i h n o to : Braunton R Westwar o z d Ho! Barnstaple 560.7 68.9 S Hartland PHartland Point LH. -

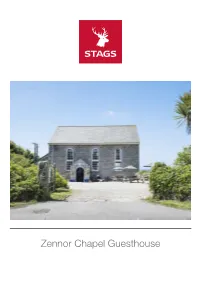

Zennor Chapel Guesthouse Zennor Chapel Guesthouse Zennor, St Ives, Cornwall

Zennor Chapel Guesthouse Zennor Chapel Guesthouse Zennor, St Ives, Cornwall, SITUATION Cornwall. The cafe currently has 30 Around five miles south-west of St. Ives, covers whilst the en-suite bedrooms Zennor is situated in an Area of comprise two doubles, two family rooms Outstanding Natural Beauty only half a and a further bedroom with a pair of mile from the majestic north Cornish bunk beds, sleeping 16 in total. coast. It is considered that further scope exists Famed for the medieval carving of a to extend the business perhaps with a St Ives - 5 miles Sennen - 15 miles mermaid inside the Parish Church and restaurant serving in the evening or even Penzance - 7 miles Coast - 0.5 mile once the home of D. H. Lawrence, the weddings (subject to obtaining all village comprises a cluster of traditional necessary consents and licences). granite buildings including the historic THE GROUNDS Tinners Arms whilst the award winning Gurnards Head Inn is around two miles There is car parking in a granite chipped distant. forecourt area to the front whilst to the rear is a lawned garden which is stream Tourism is the principal industry in the bordered. area and the landscape is a walkers THE BUSINESS paradise. Much of the surrounding land The cafe currently opens seven days a A rare chance to acquire is in the ownership of The National Trust week between 9am and 5pm from and from the village there is easy access Easter to the end of October. The an attractive lifestyle onto the scenic Southwest Coast Path enterprise is run by the Vendors together and Zennor Head. -

Cornwall Council Altarnun Parish Council

CORNWALL COUNCIL THURSDAY, 4 MAY 2017 The following is a statement as to the persons nominated for election as Councillor for the ALTARNUN PARISH COUNCIL STATEMENT AS TO PERSONS NOMINATED The following persons have been nominated: Decision of the Surname Other Names Home Address Description (if any) Returning Officer Baker-Pannell Lisa Olwen Sun Briar Treween Altarnun Launceston PL15 7RD Bloomfield Chris Ipc Altarnun Launceston Cornwall PL15 7SA Branch Debra Ann 3 Penpont View Fivelanes Launceston Cornwall PL15 7RY Dowler Craig Nicholas Rivendale Altarnun Launceston PL15 7SA Hoskin Tom The Bungalow Trewint Marsh Launceston Cornwall PL15 7TF Jasper Ronald Neil Kernyk Park Car Mechanic Tredaule Altarnun Launceston Cornwall PL15 7RW KATE KENNALLY Dated: Wednesday, 05 April, 2017 RETURNING OFFICER Printed and Published by the RETURNING OFFICER, CORNWALL COUNCIL, COUNCIL OFFICES, 39 PENWINNICK ROAD, ST AUSTELL, PL25 5DR CORNWALL COUNCIL THURSDAY, 4 MAY 2017 The following is a statement as to the persons nominated for election as Councillor for the ALTARNUN PARISH COUNCIL STATEMENT AS TO PERSONS NOMINATED The following persons have been nominated: Decision of the Surname Other Names Home Address Description (if any) Returning Officer Kendall Jason John Harrowbridge Hill Farm Commonmoor Liskeard PL14 6SD May Rosalyn 39 Penpont View Labour Party Five Lanes Altarnun Launceston Cornwall PL15 7RY McCallum Marion St Nonna's View St Nonna's Close Altarnun PL15 7RT Richards Catherine Mary Penpont House Altarnun Launceston Cornwall PL15 7SJ Smith Wes Laskeys Caravan Farmer Trewint Launceston Cornwall PL15 7TG The persons opposite whose names no entry is made in the last column have been and stand validly nominated. -

Cornwall Visitor Guide for Dog Owners

Lost Dogs www.visitcornwall.com FREE GUIDE If you have lost your dog please contact the appropriate local Dog Warden/District Council as soon as possible. All dogs are required by law to wear a dog collar and tag Cornwall Visitor bearing the name and address of the owner. If you are on holiday it is wise to have a temporary tag with your holiday address on it. Guide for NORTH CORNWALL KERRIER Dog Warden Service Dog Welfare and Dog Owners North Cornwall District Council Enforcement Officer Trevanion Road Kerrier District Council Wadebridge · PL27 7NU Council Offices Tel: (01208) 893407 Dolcoath Avenue www.ncdc.gov.uk Camborne · TR14 8SX Tel: (01209) 614000 CARADON www.kerrier.gov.uk Environmental Services (animals) CARRICK Caradon District Council Lost Dogs - Luxstowe House Dog Warden Service Liskeard · PL14 3DZ Carrick District Council Tel: (01579) 345439 Carrick House www.caradon.gov.uk Pydar Street Truro · TR1 1EB RESTORMEL Tel: (01872) 224400 Lost Dogs www.carrick.gov.uk Tregongeeves St Austell · PL26 7DS PENWITH Tel: (01726) 223311 Dog Watch and www.restormel.gov.uk Welfare Officer Penwith District Council St Clare Penzance · TR18 3QW Tel: (01736) 336616 www.penwith.gov.uk Further Information If you would like further information on Cornwall and dog friendly establishments please contact VisitCornwall on (01872) 322900 or e-mail [email protected] alternatively visit www.visitcornwall.com Welcome to the Cornwall Visitor Guide for Dog Welfare Dog Owners, here to help you explore Cornwall’s beaches, gardens and attractions with all the Please remember that in hot weather beaches may not be family including four legged members. -

Launceston-And-Districts-Fallen-From-Both-World-Wars..Pdf

This is not a complete record of all those that fell during the two wars, with some of the fallen having no information available whatsoever. However there are 222 names from within the district that I have been able to provide a narrative for and this booklet hopefully will provide a lasting memory for future generations to view and understand the lives behind the names on the various memorials around Launceston. It has not been easy piecing together the fragments of information particularly from the first world war where many records were destroyed in the blitz of the second world war, but there are many resources now available that do make the research a little easier. Hopefully over time the information that is lack- ing in making this a complete story will be discovered and I can bring all the re- cords up to date. Of course there have been many people that have helped and I would like to thank Peter Bailey, Claudine Malaquin, Dennis Middleton, Jim Edwards, Martin Kel- land, Grant Lethbridge Morris and Michael Willis for their invaluable help in compiling this homage plus the resources that are freely available at Launceston Library. My hope is that the people will find this a fascinating story to all these souls that bravely gave their lives in the service of their country and that when we come to remember them at the various remembrance services, we will actually know who they were. Roger Pyke 28th of October 2014. Launceston’s Fallen from World War One William Henry ADAMS William was born in 1886 at 14 Hillpark Cottages, Launceston to Richard and Jane Adams. -

Gardens Guide

Gardens of Cornwall map inside 2015 & 2016 Cornwall gardens guide www.visitcornwall.com Gardens Of Cornwall Antony Woodland Garden Eden Project Guide dogs only. Approximately 100 acres of woodland Described as the Eighth Wonder of the World, the garden adjoining the Lynher Estuary. National Eden Project is a spectacular global garden with collection of camellia japonica, numerous wild over a million plants from around the World in flowers and birds in a glorious setting. two climatic Biomes, featuring the largest rainforest Woodland Garden Office, Antony Estate, Torpoint PL11 3AB in captivity and stunning outdoor gardens. Enquiries 01752 814355 Bodelva, St Austell PL24 2SG Email [email protected] Enquiries 01726 811911 Web www.antonywoodlandgarden.com Email [email protected] Open 1 Mar–31 Oct, Tue-Thurs, Sat & Sun, 11am-5.30pm Web www.edenproject.com Admissions Adults: £5, Children under 5: free, Children under Open All year, closed Christmas Day and Mon/Tues 5 Jan-3 Feb 16: free, Pre-Arranged Groups: £5pp, Season Ticket: £25 2015 (inclusive). Please see website for details. Admission Adults: £23.50, Seniors: £18.50, Children under 5: free, Children 6-16: £13.50, Family Ticket: £68, Pre-Arranged Groups: £14.50 (adult). Up to 15% off when you book online at 1 H5 7 E5 www.edenproject.com Boconnoc Enys Gardens Restaurant - pre-book only coach parking by arrangement only Picturesque landscape with 20 acres of Within the 30 acre gardens lie the open meadow, woodland garden with pinetum and collection Parc Lye, where the Spring show of bluebells is of magnolias surrounded by magnificent trees. -

1268 F.Ar Corn"Tall

1268 F.AR CORN"TALL. FARMERs-continued. Peters Edward, Trethinna, Alternun,' Phillips Thomas, Vounder, St. Blazey,. Pender WiIliam Frederick, Bryher, St. Launceston Par Station RS.O Mary's, Islands of Scilly Petersl".Beacon,St.Agnes,ScorrierR.S.O Phillips WaIter, Lombard, Lanteglos, Pender William John, Bryher, St. Peters Hugh, Burgotha, St.. Stephen's- Fowey RS.O Mary's, Islands of SCIlly in-Brannell, Grampound Road Phillips W. J.Bokiddick,Lanivet, Bodmin. Pendray James, Nancemelling, Gwy- Peters John,Kennall mills, St.Stythians, PhillipsWm.Egloshyle.SladesBrdg.RS.O thian, HayIe Perran-Arworthal RS.O Phillips Wm. Hendra, Kenwyn, Trnro Pendray Peter, Kehelland, Camborne Peters John, ~ancemellan, Kehelland, Phillips WiIliam, Pool, Carn Brea RS.O Pendray William, Bodithiel, St. Pin- Camborne PhillipsW.Rosenea,Lanlivery,Lostwithiel nock, Liskeard Peters J. Tremorvab, Budock, Falmouth Phillips William, Trebiskin & Ellenglaze, Peneluna William, Calvadnar:k, Carn- Peters John, Windsor Stoke, Stoke Cubert, Grampound Road menellis, Helston Climsland, Callington RS.O Phillips William John, Lawhibbet, St. Pengelley Nicholas, Trevawden, Herods- Peters S. GiUy vale, Gwennap, Redruth Sampson's, Par Station R.S.O foot, Liskeard Peters Thomas, Lannarth, Redruth Phillips WiIliam John, Tregonning,. Pengelley William, Carythenack, Con- Peters William, Beacon, St. Agnes, Luxulyan, Lostwithiel stantine, Penryn Scorrier R.S.O Philp John, Yolland, Linkinhorne,. Pengelly Miss Grace, Boswarthen, Peters W. Illand, North hill, Lanceston Callington RS.O Madron, Penzance Peters William,Trewithen, St.Stythians, Philp John, jun. Lancare & Cardwain &; Pengelly James, Tresquite mill, Lan- Perran-Arworthal R.S.O Cartowl, Pelynt, Duloe RS.O sallos, Polperro RS.O Petherick Thomas, Pempethey, Lan- Philp John Pearce, Downhouse, Stoke Pengelly John Henry, Wallace &; Lower teglos, Camelford Climsland, Callington RS.O Lacrenton, St. -

Edited by IJ Bennallick & DA Pearman

BOTANICAL CORNWALL 2010 No. 14 Edited by I.J. Bennallick & D.A. Pearman BOTANICAL CORNWALL No. 14 Edited by I.J.Bennallick & D.A.Pearman ISSN 1364 - 4335 © I.J. Bennallick & D.A. Pearman 2010 No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without prior permission of the copyright holder. Published by - the Environmental Records Centre for Cornwall & the Isles of Scilly (ERCCIS) based at the- Cornwall Wildlife Trust Five Acres, Allet, Truro, Cornwall, TR4 9DJ Tel: (01872) 273939 Fax: (01872) 225476 Website: www.erccis.co.uk and www.cornwallwildlifetrust.org.uk Cover photo: Perennial Centaury Centaurium scilloides at Gwennap Head, 2010. © I J Bennallick 2 Contents Introduction - I. J. Bennallick & D. A. Pearman 4 A new dandelion - Taraxacum ronae - and its distribution in Cornwall - L. J. Margetts 5 Recording in Cornwall 2006 to 2009 – C. N. French 9 Fitch‟s Illustrations of the British Flora – C. N. French 15 Important Plant Areas – C. N. French 17 The decline of Illecebrum verticillatum – D. A. Pearman 22 Bryological Field Meetings 2006 – 2007 – N. de Sausmarez 29 Centaurium scilloides, Juncus subnodulosus and Phegopteris connectilis rediscovered in Cornwall after many years – I. J. Bennallick 36 Plant records for Cornwall up to September 2009 – I. J. Bennallick 43 Plant records and update from the Isles of Scilly 2006 – 2009 – R. E. Parslow 93 3 Introduction We can only apologise for the very long gestation of this number. There is so much going on in the Cornwall botanical world – a New Red Data Book, an imminent Fern Atlas, plans for a new Flora and a Rare Plant Register, plus masses of fieldwork, most notably for Natural England for rare plants on SSSIs, that somehow this publication has kept on being put back as other more urgent tasks vie for precedence. -

COM 575 Wicca, Treveal, Tremedda, Tregerthen36 Long Stone Croft

Application Decision Hearing held on 18 February 2015 by Heidi Cruickshank BSc MSc MIPROW Appointed by the Secretary of State for Environment, Food and Rural Affairs Decision date: 21 April 2015 Application Ref: COM 575 Tremedda, Tregerthen, Wicca and Treveal Cliff, Zennor, Cornwall Register Unit No: CL7041 Commons Registration Authority: Cornwall Council The application, dated 26 March 2013, is made under paragraph 4 of Schedule 2 of the Commons Act 2006. The application is made by Mr D Coles on behalf of Save Penwith Moors. The application is to register waste land of a manor in the Register of Common Land. Decision 1. The application is approved in part. The land outlined and cross-hatched in red on the plan attached to this decision shall be added to the Register of Common Land (“the RCL”). Preliminary Matters Guidance 2. The applicants, Save Penwith Moors (“SPM”), argued that the Department for Environment, Food and Rural Affairs (“defra”) guidance that should be referred to in this case was that which was extant at the date of their application. The application was received by Cornwall Council, the Commons Registration Authority (“the CRA”) on 10 April 2013. 3. Cornwall was one of the pilot areas and, therefore, the “Part 1 of the Commons Act 2006, Guidance to commons registration authorities and the Planning Inspectorate for the pioneer implementation” was relevant guidance. Revisions have been made, with the latest, published in December 2014 (“the guidance”). “Part 1 of the Commons Act 2006, Guidance to commons registration authorities and the Planning Inspectorate”, version 2.0 relates to the full implementation of Part 1 of the Commons Act 2006 (“the 2006 Act”) in a minority of registration authorities and the partial implementation in remaining registration authorities through The Commons Registration (England) Regulations 20142. -

Cubert Housing Needs Survey Full Report

Cubert Parish HOUSING NEED SURVEY Report Date: 10th May 2019 Version: 1.1 Document Final Report Status: Affordable Housing Team, Author: Cornwall Council [email protected] Tel: 01726 223686 Cubert Parish Housing Need Survey Report Contents 1. Introduction ............................................................................................................................... 3 2. Current Housing Need Information .................................................................................. 4 2.1. Registered need on Cornwall HomeChoice ............................................................ 4 3. Survey Methodology ............................................................................................................... 4 3.1. Location and geographic extent of survey ............................................................ 4 3.2. Survey methodology ...................................................................................................... 5 3.3. Survey structure .............................................................................................................. 5 3.4. Report Format ................................................................................................................... 5 4. Survey Data ............................................................................................................................... 6 4.1. Summary of survey response rate ........................................................................... 6 4.2. Analysis of sample