Fountain Pens, Ink Wells, Blotters and the Changing Face of Time H

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Ballpoint Basics 2017, Ballpoint Pen with Watercolor Wash, 3 X 10

Getting the most out of drawing media MATERIAL WORLD BY SHERRY CAMHY Israel Sketch From Bus by Angela Barbalance, Ballpoint Basics 2017, ballpoint pen with watercolor wash, 3 x 10. allpoint pens may have been in- vented for writing, but why not draw with them? These days, more and more artists are decid- Odyssey’s Cyclops by Charles Winthrop ing to do so. Norton, 2014, ballpoint BBallpoint is a fairly young medium, pen, 19½ x 16. dating back only to the 1880s, when John J. Loud, an American tanner, Ballpoint pens offer some serious patented a crude pen with a rotat- advantages to artists who work with ing ball at its tip that could only make them. To start, many artists and collec- marks on rough surfaces such as tors disagree entirely with Koschatzky’s leather. Some 50 years later László disparaging view of ballpoint’s line, Bíró, a Hungarian journalist, improved finding the consistent width and tone Loud’s invention using quick-drying of ballpoint lines to be aesthetically newspaper ink and a better ball at pleasing. Ballpoint drawings can be its tip. When held perpendicular to composed of dense dashes, slow con- its surface, Bíró’s pen could write tour lines, crosshatches or rambling smoothly on paper. In the 1950s the scribbles. Placing marks adjacent to one Frenchman Baron Marcel Bich pur- another can create carefully modu- chased Bíró’s patent and devised a lated areas of tone. And if you desire leak-proof capillary tube to hold the some variation in line width, you can ink, and the Bic Cristal pen was born. -

Writing Instruments 1.800.877.8908 93

92 Russell-Hampton Company WRITING INSTRUMENTS www.ruh.com 1.800.877.8908 93 Waterman Pens Detail 92 Russell-Hampton Company www.ruh.com 1.800.877.8908 93 Serving Rotarians Since 1920 A. R66032 Quill® Heritage Roller Ball Pen Features include: newly designed teardrop clip & inlaid feather band, high gloss black lacquer cap, gold accents, fine-point black Roller Ball refill, with full-color slant top Rotary International logo, & handsome display box. Lifetime guarantee. Unit Price $34.95 • Buy 3 $32.95 ea. • Buy 6 $30.95 ea. • Buy 12+ $29.95 ea. B. R66040 Quill® Heritage Roller Ball Pen Elegant teardrop clip and inlaid feather band highlight this beautiful brushed chrome, smooth writing Quill® rollerball pen. Rotary International emblem in crown. Lifetime guarantee. Gift Boxed. Unit Price $34.95 • Buy 3 $33.20 ea. • Buy 6 $31.45 ea. • Buy 12+ $29.70 ea. C. R66012 Waterman® Hemisphere Black Pen & Pencil Set • Classic high gloss black lacquer finish complimented with 23.3-karat gold electroplated clip & trim. Die-struck Rotary emblems affixed to the crowns. Ball pen is fitted with a black ink, medium point refill. Pencil is fitted with 0.5mm lead. Waterman Signature Presentation Blue Box with satin lining. Unit Price $107.95 • Buy 2 $102.50 ea. • Buy 3+ $97.25 ea. D. R66011 Waterman® Hemisphere Black Ball Pen • Same ball pen as sold in above set. Water- man Signature Presentation Blue Box with satin lining. Unit Price $51.95 • Buy 3 $49.35 ea. • Buy 6 $46.85 ea. • Buy 12+ $44.55 ea. -

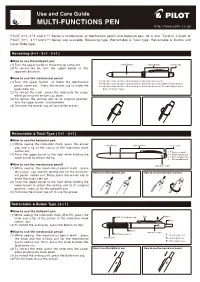

Multi-Functions Pen

Use and Care Guide MULTI-FUNCTIONS PEN http://www.pilot.co.jp/ PILOT 2+1, 3+1 and 4+1 Series-a combination of mechanical pencil and ballpoint pen, all in one. Total of 4 kinds of PILOT 2+1, 3+1 and 4+1 Series are available : Revolving type, Retractable & Twist type, Retractable & Button and Lever Slide type. Revolving (4 +1 . 3 +1 . 2 +1 ) ●How to use the ballpoint pen (1) Turn the upper barrel to make the tip come out. Lower Barrel Upper Barrel Eraser Cap (2) To retract the tip, turn the upper barrel to the opposite direction. ●How to use the mechanical pencil (1) Turn the upper barrel to make the mechanical 2+1 (Mechanical pencil, Black ink ballpoint pen & Red ink ballpoint pen) 3+1 (Mechanical pencil, Black ink ballpoint pen, Red ink ballpoint pen & Blue ink ballpoint pen) pencil come out. Press the eraser cap to make the 4+1 (Mechanical pencil, Black ink ballpoint pen, Red ink ballpoint pen, Blue ink ballpoint pen & lead come out. Green ink ballpoint pen) (2) To retract the lead , press the lead onto the paper while pushing the eraser cap down. (3) To retract the writing unit to its original position, turn the upper barrel anticlockwise. (4) Unscrew the eraser cap off to use the eraser. Retractable & Twist Type ( 3 +1 . 2 +1) ●How to use the ballpoint pen (1) While seeing the indication mark, press the eraser Lower Barrel Upper Barrel Eraser Cap cap and a tip of the colour of the indication mark 0.5 comes out. -

Handwriting Today . . . and a Stolen American Relic

Reviews Handwriting Today... and A Stolen American Relic WILLIAM BUTTS FLOREY, Kitty Burns. Script and Scribble: The Rise and Fall of Handwriting. Brooklyn: Melville House Publishing, 2009. 8vo. Hardbound, dust jacket. 190pp. Illustrations. $22.95. HOWARD, David. Lost Rights: The Misadventures of a Stolen Ameri- can Relic. Boston: Houghton Mifflin Harcourt, 2010. Small 4to. Hardbound, dust jacket. 344pp. $26.00. If you’re anything like me, handling handwriting from many eras on a daily basis, you get sick and tired of the endless refrain from the general public when viewing old documents: “People all had such beautiful handwriting back then!” or, conversely, “No one writes like that today!” Et cetera—ad nauseum. I’ve almost given up refuting these gross generalizations, but “in the old days” I’d pull out letters from, say, Horace Greeley, the Duke of Wellington, a Civil War soldier and other notori- ously illegible scribblers to prove that every age has its share of beautiful penmanship, horrid penmanship and mediocre pen- manship. And as for modern penmanship, most of the examples of current penmanship I see are in the form of personal checks MANUSCRIPTS, VOL. 62 235 NO. 3, SUMMER 2010 236 MANUSCRIPTS (thankfully), and there too I find a mix of beautiful, horrid and mediocre penmanship. The more things change, the more they you-know-what. Which is one beef I have with Kitty Burns Florey in her oth- erwise enjoyable Script and Scribble: The Rise and Fall of Handwrit- ing. Other than the uninitiated general public cited above, the other group that unfairly bemoans current penmanship are the handwriting snobs (which I don’t consider Florey)—elit- ists whose devotion to pseudo-Palmerian calligraphy or other esoteric specialties blinds them to the simple, honest, unsophis- ticated attractiveness of the day-to-day script of ordinary persons who’ve never studied calligraphy. -

The History of the Ballpoint Pen

89 | Ezra’s Archives My Utilitarian Chinese Memento: The History of the Ballpoint Pen Robert Schur Made in China For all intents and purposes, my three-week sojourn through China should have given me an appreciation for the Chinese people and their culture, a more thorough understanding of life under a Communist regime, and perhaps some knowledge of handy Chinese phrases. Indeed, I left the country with all of those things, but I also found myself fascinated with the most mundane of souvenirs: the ballpoint pen, particularly the one that I acquired while studying at Zhejiang University in Hangzhou, China, during a trip with fifty other Cornell students sponsored by Cornell University and the Chinese government. When we arrived for our orientation, we found each place set with an array of official University and government forms. Next to these stacks of paper rested green triangular ballpoint pens filled with blue ink, sporting retractable points, each emblazoned with the university’s name, phone number and website. Considering my at-best-rudimentary Chinese language skills, this pen proved quite handy, as I would have been at a loss to ask a hotel clerk or cashier to borrow one. Beyond this small bit of good fortune, I thought little of the pen as I carried it in my pocket throughout the trip until I was making notes on a lecture by one Dr. Wu Xiaobo about the Chinese economy. As he detailed the various aspects of China’s post-Mao era economic reforms, he informed us that 80 percent of all of the world’s pens are made in China, and 70 percent of The History of the Ballpoint Pen | 90 worldwide pen components are made in a particular district, the name of which my sloppy handwriting ironically rendered unintelligible.1 While the veracity of Chinese economic statistics has been hotly contested recently, and reliable data on Chinese ballpoint pen manufacturing data is all but nonexistent, Wu’s remarks nonetheless made me reconsider the oft-overlooked history of the pen that I held in my hands, just one of the billions of ballpoints across the world. -

2021 Premium Business Gifts Advertise with Lamy

2021 Premium Business Gifts Advertise with Lamy Fountain pens Ballpoint pens Rollerball pens Mechanical pencils Multisystem pens Notebooks Set offers Lamy’s wide range of promotional articles is available solely to commercial enterprises, businesses and Contents freelancers. Private sale is not possible. Sending a lasting message ................... 3 LAMY AL-star EMR ......................... 44 Taking responsibility – shaping the future ....... 4 LAMY twin pen ............................. 46 From Heidelberg into the world ............... 8 LAMY tri pen ............................... 48 LAMY safari . 10 Notebook assortment from Lamy ............. 50 LAMY AL-star .............................. 12 Sets ....................................... 54 LAMY xevo ................................ 14 Cases ..................................... 55 LAMY noto ................................ 16 LAMY ideos ............................... 56 LAMY logo ................................ 18 LAMY studio ............................... 58 LAMY tipo ................................. 28 LAMY scala. 60 LAMY econ ................................ 30 LAMY 2000 ................................ 62 LAMY pur .................................. 32 LAMY 2000 M ............................. 64 LAMY swift ................................ 34 LAMY dialog cc ............................ 66 LAMY cp1 ................................. 36 LAMY dialog .............................. 68 LAMY pico ................................ 38 LAMY imporium ............................ 70 LAMY -

Writing Instruments & Accessories

Writing instruments & Accessories 2015 100 YEARS OF CREATIVITY AND EMOTION Caran d’Ache is delighted to celebrate its 100th anniversary in 2015. Founded in 1915 in Geneva, the company was renamed ‘Caran d’Ache’ in 1924 as a tribute to the famous French illustrator, Emmanuel Poiré. The company initially specialised in graphite and coloured pencils and diversified its activities to include wax oil pastels, mechanical pencils and the first ballpoint pens.T he expansion of the company, combined with the development of the Colour, Writing Instruments and Office ranges, contributed to the international renown of the Manufacture. Therefore, thanks to its rich history, the Caran d’Ache creations have been a true inspiration for many generations of enthusiasts for a hundred years. “COLLECTION Anniversaire” Caran d’ACHE To mark its 100th anniversary, Caran d’Ache invites you to discover a new collection that has been created especially for this occasion. More than 90 art crafts are expressing themselves through unique creations that take their inspiration from five iconic products:T echnograph, Fixpencil, Prismalo, Ecridor and 849. The Caran d’Ache artisans have imagined and designed each of these items to develop a limited edition collection that is already iconic and animated by the famous character “Bonne-Mine”, the historic emblem of Caran d’Ache. TECHNOGRAPH 100 ANS 4 graphite pencils HB, B, 2B, 3B and a sharpener Ref. CA0777.304 PRISMALO 100 ANS 25 watersoluble pencils Ref. CA0999.325 849 100 ANS Metal ballpoint pen and its giant Goliath cartridge Ref. CA0849.100 ECRIDOR 100 ANS Ballpoint pen Guillochage Chevron 100 ans FIXPENCIL 2MM 100 ANS Ref. -

Calligraphy-Magic.Pdf

Calligraphy Magic How to Create Lettering, Knotwork, Coloring and More Cari Buziak Table of Contents Table of Contents Introduction Glossary of Terms CHAPTER 1 Calligraphy Tools and Supplies CHAPTER 2 How to Make Calligraphy Strokes CHAPTER 3 15 Alphabets From Basic to Fancy CHAPTER 4 Ornamentation, Gilding & Coloring CHAPTER 5 12 Calligraphy Projects Step by Step STATIONERY AND EVENT ANNOUNCEMENTS Bookplates Greeting Cards Bookmarks Logos Business Cards and Letterhead Wedding Announcements Invitations Place Cards and Thank-You’s DISPLAY PIECES Monograms Quotations Certifi cates Lettering with Celtic Decoration Illustrated Poems Lettering with Dragon Artwork CHAPTER 6 Creating Your Own Computer Fonts Pre-printed Celtic Knotwork Grid Paper Pre-ruled Calligraphy Practice Pages Index About the Author Dedication Acknowledgments Introduction Introduction Calligraphy is a fun craft to learn, as well as a useful one. Far from being an obsolete skill, more and more people today are picking up the pen and creating their own greeting cards, wedding invitations, fine art projects, and even creating their own computer fonts! In the old days, calligraphy tools were unique and specically crafted to their task. Today, a calligrapher has a wide variety of tools from which to choose, from traditional to completely modern, even digital! Calligraphers can now experiment with their artistic expression, freely mixing creative ideas and elements together to explore new artforms with their projects. In this book we’ll examine the basic techniques of calligraphy, covering calligraphy hands suitable for a wide variety of projects and easy for a beginner or intermediate calligrapher to practice and learn. We’ll also cover easy decorative techniques such as watercolor painting, Celtic knotwork, gold leang and illustration ideas to create a “toolkit” of creative techniques. -

Writing Instruments Inks: Microspectrophotometry Forensic Analysis and Characterisation

Writing instruments inks: microspectrophotometry forensic analysis and characterisation Ana Cristina de Almeida Assis Scientific Police Laboratory, Judiciary Police, Portugal Filipa Isabel Romano Inácio Department of Chemistry, University of Coimbra, Portugal João Sérgio Seixas de Melo Coimbra Chemistry Centre, Department of Chemistry, University of Coimbra, Portugal Carlos Farinha Scientific Police Laboratory, Judiciary Police, Portugal Abstract An important aspect in the analysis of written documents is the type of materials used in questionable documents. The present study aims to characterise and create a database of the absorption spectra in the visible region, obtained by microspectrophotometry (in reflectance mode), of inks from blue and black writing instruments, such as ballpoint pens and liquid ink pens (rollerball pens, gel pens, felt-tip pens and fountain pens). The study was performed with 167 ink samples of 36 different brands commonly used in national and international markets. To validate the possible use of the database a preliminary blind test with 22 samples yielding a consistent and accurate match of 13 samples revealed that this technique has a good potential to obtain a list of inks with the same spectral characteristics. To evaluate the differentiation level of this method the samples were grouped based on the overlap of the 1st derivative spectra. As this grouping systematisation was found to present some limitations when we have a large number of samples, a multivariate analysis of the data was made. For this, a hierarchical cluster analysis (HCA) was performed. The discrimination power was calculated and compared with another works. Keywords Document examination, ink analysis, blue and black writing instruments, microspectrophotometry, hierarchical cluster analysis (HCA) 187 European Police Science and Research Bulletin · Issue 16 · Summer 2017 Introduction The technological development of the past 30 years has put us in a digital era, in which we increasingly resort to electronic means for identification and commercialisation pur- poses. -

Today Is National Ballpoint Pen Day

Today Is National Ballpoint Pen Day Grab your ballpoint pen and write this on your calendar. June 10th of each year is National Ballpoint Pen Day. This particular day commemorates the ballpoint pen and marks the anniversary of the patent filing on June 10, 1943. Before 1943, anyone who wanted to write a letter or scribble some notes on a piece of paper would have to use a fountain pen or pencil. Now the dominant writing instrument, the ballpoint pen was originally conceived and developed as a cleaner and more reliable alternative to the quill and fountain pens. Every day, millions are manufactured and sold worldwide. Lost cost and its omnipresence assure that there is always a ballpoint pen within your reach. In earlier years, many attempts by inventors lead to failed patents as their inventions did not deliver the ink evenly and also had overflow and clogging issues. Brothers Laszlo and Gyorgy Biro are credited with the invention of the ballpoint pen and obtained a patent in June of 1943. Before ballpoint pens, thinkers relied on messy quill pens and fountain pens to jot down their thoughts. These pens leaked and smeared and were not well equipped for the on-the-go lives of pen users. The rise of the ballpoint pen made writing convenient for secretaries and fighter pilots alike. By World War II, the British Parliament had purchased the patent rights for the ballpoint pen from the Bíró brothers, and the rest was written into ballpoint pen history—with a ballpoint pen of course. To realize the importance of the ballpoint pen, consider the fact that the ballpoint pen wasn’t popularized until after commercial aviation was in widespread use. -

The Document

Made to last For you For everyone 2016 Made to last For you For everyone 2016 Mamma’s notebook — 02 The call of the (Brazilian) wild — 04 Sideburns, three-day beard… you name it! — 06 Of course the world is changing... — 08 Tibo’s prize — 10 A LEGACY OF LEADERSHIP, FROM ONE GENERATION TO THE NEXT INTERVIEW — 14 KEY FIGURES — 16 MEMBERS OF THE BOARD AND LEADERSHIP TEAM — 22 SHARING THE PASSION FOR OUR PRODUCTS GUARANTEEING PRODUCT EXCELLENCE GLOBALLY — 26 ACCESSIBLE, ADAPTABLE… — 28 CLOSE TO YOU — 30 SHARING OUR COMMITMENTS SUSTAINABLE DEVELOPMENT — 34 BUILDING THE TEAM — 36 GIVING — 37 SHARING OUR CULTURE OF INNOVATION NEW ADDITIONS 2016 — 38 We offer simple, inventive and reliable choices for everyone, everywhere, every time. Our ballpoint pens, lighters and shavers are subtly connected to life moments. A ritual, a habit, a feeling, a taste, a new gesture… BIC® products are markers and transmitters, triggering memories, discoveries, learning experiences, bridging the generations of yesterday, today and tomorrow. Connecting those who use and love them. Like you, like everyone, like the people who share their BIC® testimonials in the pages that follow. For the first time. And forever after. 01 Made to last. For you. For everyone. It’s funny how it started. Ever since I can remember, there’s been a spiral notebook in Mamma’s bag or jean pocket. The cover is plain with dog‑eared corners, but the orange spiral catches your eye. That’s where she stores her trusty ballpoint pen with the blue cap*. Full of notes and doodles, with clippings, photos, and visiting cards spilling out the sides, her notebook is like a portable treasure chest! When I was old enough to notice, I would see her reach for it to jot down a thought, an idea, some clever thing my little brother or I would say… and shopping lists that branched out like trees! Before I knew how to read or write, Mamma’s notebook CHIARA, AGE 14, MILAN, ITALY I imagined her little book held all our secrets. -

Universal Penman Rollerball Nib the J-Form Dip Pen Allography Cursive

eraser An eraser or rubber is an article of stationery that is used for removing pencil and sometimes pen writings. Erasers have a rubbery consistency and are often white or pink, although modern materials allow them to be made in any cursive allography colour. Many pencils are equipped with an eraser on one Cursive is any style end. Typical erasers are made from synthetic rubber, but The letter a is depicted of handwriting that is dip pen more expensive or specialized erasers can also contain vi- fountain pen with two common glyphs nyl, plastic, or gum-like materials. Other, cheaper erasers ballpoint designed for writing A dip or nib pen consists of a metal nib A fountain pen is a nib pen that, unlike its predecessor the dip pen, contains an internal reservoir which differ between can be made out of synthetic soy-based gum. notes and letters quickly with capillary channels mounted on a of water-based liquid ink. From the reservoir, the ink is drawn through a feed to the nib and then typefaces and handwrit- A ballpoint pen has an internal chamber filled with a vis- by hand. In the Arabic, to the paper via a combination of gravity and capillary action. As a result, the typical fountain pen ing styles. Allography cous ink that is dispensed at tip during use by the rolling handle or holder, often made of wood. Latin, and Cyrillic writing Other materials can be used for the requires little or no pressure to write. is this variation in how action of a small metal sphere made of brass, steel or systems, the letters in letters are formed.